Exploring Achievement: Factors Affecting Native American College

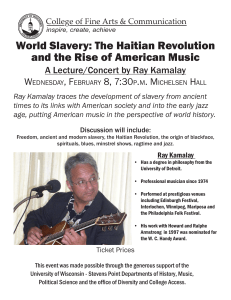

advertisement