The Making of a Journalist: The New Zealand Way

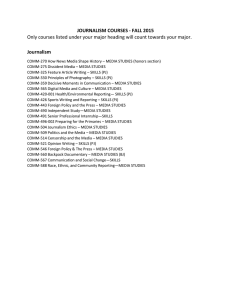

advertisement