ISSN 1171-0462 April 2013 • Vol 60 • Issue 1

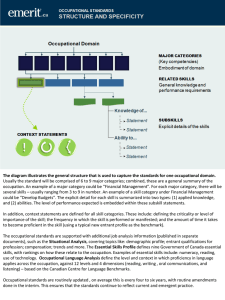

advertisement