NORTH MIERJCANF"REETRAD:E Wellington

advertisement

INTEGRATING ,ENVIR.oNN!ENTAL I'ROTECTION AND

NORTH MIERJCANF"REETRAD:E

by

Peter M. Emerson and Alan C. Nessman*

for the

Australian AgricultucalEconomics Society

38th Annual Conference

Victoria University

Wellington, New Zealand

February 7-11, 1994

Introduction

Revolutions in technologyanclcommnnicationilavegreatly#.}nbanced.Ollf capncity

transfer ideas, people, gouds andser\:1ces, capital, and pollution .across nation31

boundades.These'transfers crentea growing interdependence .... aconvergence of

interests ,. .. among very different and sovereign nntions. li1is interdependence is

:routmelye>,:pressed though the commercIal exchange: of goods! services, and capital. It is

tttsoe~-pressed tbrougbconc.erns for important social values like the environment~ worker

safetyJ'and buman rights ..

to

On. Jamlary 1, 1994, Canada, the United States.• and ~1exico began to further

their economic ~ifairs.through a new regional trade pactc~eated by the North

Amerlcnn. Free Trnde Agree.ment (NAFTA). This historic setting offers an opportunity

to e~~ll1ht:l.," how the gro\\ring interdependence .among these sovereign nations might

('ontribtite to solving the difficult problem ofenviron.m.ental degradation.

lnt\~grate

In partit1l1of, is there a conve.rgence of interestsinvohingfuternational trade and

social values that can he used to design a strategy that \\111 allow the trading partners to

achieve hig!:er lev~ls of envlrollll1ental protection? Oft will the specific objectives of free

tradeniand environmental adv()cates :result only in unproductive confrontations?

AU$\\,ets to these que~tions are Important in North Alnerica and in avadety of

international settings.

During the NAFrA debate, trade and environment issuesemetged in a

controversial manner, with much attention paid to thecontlicts between trade and

envlloru:ne,utal polides. The t\'lO policyregitnes are dpe for conflict because the

disclpl;ues are themselves 'bighlycomplAx and be<.:ause they are 'managed by specialists

with widely differing expecta.tions of what is attainable~ V'lihUe such .conflicts can easily

beexaggeril.ted, there are sevel'nl PI)ints nt which trade and environmental regimes .might

be reconciled.

Succ<!ssor failure in this enderivQr will be determined by n host of economic,

polidcaland cultural factors. BUl, if a succcrsful strntegycan be found it could build on

the fact that both trade liberalization and environmental regulation have as their

pri.ncipal goal the more efficient use of available resources (Repetto) .• Indeed, if they

can be adopted, policies that promote ecoromic grmvth and environmental quality

among trading partners would provide a stable base for international cooperation and

rnoresustrunable development.

The purpose of this paper .is to describe tbe role environmental issues and interest

groups played in shaping the NAFfA and its related agreements. It outline.') specific

environmental problems that "\vere raised during the negotiation of the trade agreement

and documents steps ~hat were taken to address these problems. This may help in

unde.rstanding implementation of the NAFfA and in deaUng with issues that were not

1

fully r.ef,olved in the negotiation. process. It maynlso haveimplicutions for future trade

and~n"ir(mmental agreements beyond NQrt.h A:mericn. The-need to reconcile trade and

tt

environrtlel~tal policy ·w.aserophasized attbe 1992"Earth SUlnmit in Rio de l'uneiroand

is Ukely to confront governments for many years.

The p~lper proceeds by first describing somegenerai chnrncterlstics.of the

NAFTA., TIle secondsectilm. documents fOllr categories ·oftoncerns that were raised by

environmenlulist.) in the dehate. The .tblrd sectione~'Plains how trade .negotiators and

politicalle.nde.rs responded to problems raised by environmentalist.s., The 'paper ends

with brief commentS on bow tbe l'tJ.\.Fr.;.\ 'mIght influence what 'happens nextns trnde

and env.ironment agendainterac1*

\-Vhatls TIle NAFTA?

Cross,.border trade in North A.meriea.is substantinland gro'ving, and it is

dominated by trade lllvolvingtbeUnlted Sl'{l.tcs. Tn. 1992, U.S... Canndian iwo.,way trnde

(imports ande:\-ports) accounted fornbout 13 percent of the regi"uisH)ml trade ill

me rchu:n dise; U.S. ·~lerltzn.n for about Z6 percent, ,and Canad.i:~n .. ~r.exico.n for about

one percent (Congress!omdBudget Office). \Vhiletrade with Canada and :Nle:dco is a

significant share of aU U.S. trade) theUnhed States does not depend on their trade to

the same extent that Canada. and .Nfe:tico depend on trade with the United States.,

The United Stat,esand Canada enjoy strong trade and illvestm.ent link~, but' they

also sbarea long history of commercial di:-putes. In 1989. they entered into the U.S....

Canndn. Free Trade Agreement. 1bisttnde agr.e.eroent was n.egotiated, in. large mensur~;

t.o re~olve frictions that have marred conunercial relations between the t\\'ocountries in

areas such as energy, mvestments,so(twood lumber andautornoti\'e products. It \vas also

seen as a vehicle to move regional trade Ubero.lizution.ahead Qf slowermultilat:!l'·:ll lrude

talkst lvlanyaspects of the C.S... Canada Free Trade Agreement are included in the

NAFTA~

Despite broad public. support for the enVirOnJllent nnd a host of U.S. ~ Canadian

m,ltural resource controversies, enviromnental concerns did not ph1,Y a significant role in

shaping the U.S~ '" Canad.ian trade negotiations. However~ environmentaJconcerns were

not entirely absent, especially in Canada. Although, unsuccessful .in mod.ifyiog the trade

agreement.,. Canndian environmental groups did make a vigorous c.ase nguinst free trade

using many arguments that again surfaced in the NAFTA debate (Pearsm. ).

Since 1965, tbet:nhed States und ~1exico have shared a partIal IIfree trade"

experiment called the Border Industrialization Program n:.S. C()ngress~ OTA).This

program liberalized toreignmvnership restrictions on land and other assets in ~fexko

and granted special trade status to businesses that export their products. Typically, the

::vrex.ican..:bnsed pIanISt r.uUedttmuquiladoras," import manufacturing :tllatenals and

2

1I1UC :lines

free of duty lntoNlexico nndexport finisbedor semi:"finished products t.o

U.S. subject to asmn:U value-added duty•. hddulh~ (be :mnquilndorns W~rI~ allowed the

operate {lnly in the border area. But since lheeutly 1970s, speclnllrade sttttus tt)

hus been

grnnted,witha fewexceptious" to companies j'Jco,ted elsewhe.re In fi;fe~\i.co.

In themid.. 1980s, tbe~rexican .governmentadopted au outward..lookingttllo

mnrket.. onenterl .agenda.representing a n1ttjor breakw ilh pas·teconami

cand fore.ign

policy. ;\long\'vithdomestlcprograms of fiscal discipline, deregulation :and privatiz

ation,

IVfexico also joined tbeQ.e.'1~ll Agreenlenton Tariffs and 'Trade (GATT) in

1986

..

This

wnsaccomparried by the removal of some restrictions on. foreign investment,

relative

ly

large reductions in tadffsJand the eH.mlnatiOllof certain" "irements for import

UceUSeS.

Asa re~ultof thesen~don~i by ~.rexiC'nn:nda relativelyopeu U.S" marke

between thet:\vo countries hus ;e:<panded rapidly in. recent years. Today, ~rexictt trade

an economy amounting to flve percent o.f U.S. gross domestic product ..... is t.t1.e o-· \vith

States' third-largest trading pOItner afte.r Canada ;and Japan. And Nte:dco"s Gnited

economy is

t

very beavilydependent on the United States. Two .. thlrds"Of all ~'rexie

an exports are sold

in the -U~S. and 70perce.nt <.\r Nlexicnn imports are purchased in the C.S. Similar

ly, two ..

thirds of aU new direct foreign investment in !vlexh:;,} originates in the l:.S.

(Congressional Budget Office).

In early 19QO President Saliuas de Oarto.ri approncbed Presidcnt13ush to

negotiate a bilateral free trade ngteement.E.'\:pandedto indudeCannda in Januar

1991, the proposetl i.lade agreement ,- while rerycontroversia{ in munyquarters y

enJo}ed the suppOrt of politi.cnl le'~dersnt the highest lev-cIs from the begi.nn

ing.

j

The NAFTA, wbichentered into force

011 January

1, 199i, will create

the hu~gest

free tradearen in the world, \v;tb 360 million peo-p.le .und an annual gross nationa

l

produ.ct totalling ovet S6 trillion. Net economic bihefits are ex-pected to flow

fr.o.m

the

new tradeaYleem.eot, but they are UmJted by the c!t.rrent low level of traden.nd

in¥estment barriers between the l':nited States and tanad,l~ and the relativelv

sm~lIl size

of tbe !\le:dcun e.conomy(flutbauernnd Schott~ 1991; Krugman)*

"

The trade and Investm.cnt liberalizing objectiv~s of the :NAFI:~ win affect nearl~~

every flSpect of businessacdvity in North America (s\·e Table I). Itcnnm'ins.

scbedules

for the phased eUminationof t~lriff and most nontarH f barriers on regionultrade

'within

ten years, although a fe\"l import-sensitive productswil hZlve n t5 . .year transit

ion

l,eriod.

It :lisocontains .rules fClr converting nontariff barriers ~{) tariff harrier5~ rules

for

determining the origin of trade goods; special provisin '.lS f(lf inteUectuai proper

t;,ervices, investment, and governnlent procurement.; u"ttriety of dispute settlemty.

provisions; and numerous exceptions to the generalterk1s and conditions of ent

the

llgreement. A country ;Olny whhdru\v rf{un the NAFTA six nlonths Ufif.!'f it provide

sa

\vntten notice ofwithdrnwul to the other countries.

3

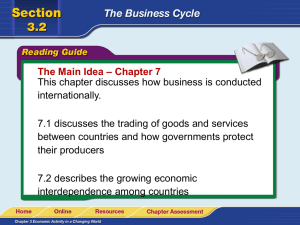

TABLE 1: ObJe.ctlves of tbe North American ,Free; Trade Agreement

Article, 102: Objectives

The objectives of this Agreement, as t'libonlted more specu:\!aUythrougb its

principles and rules. including national treatment, m.oSt "fnvored,.natlon trea.tment and

transparency. are to!

(a)

elhninnte barriers to trade ill, and facilitate the cross-border movement of,

goods and services betweetl the terntonesot the; Parties,

(b)

promote conditions of fair competition In the free trade area;

(c)

increase substantially investUlent opportunities :in the terrItories

Parties;

(d)

provide adequnteand effective protection and enforcement of intellectual

property rights in each Purty's terntory;

f')f

the

"

.(e)crenteeffective procedures for the implementation and appli~ation of this

Agreement; .fOf its joint adtninistrationand for the resoLution of disputes~

and

(f)

establish a framework for funber trilater3.1~ regional and multilateral

cooperation to expand and e'lhan~e the benefits of this Agreement.

Source; North American Free Trade Agreement. 1993

4

Investment pro*risionsof the NAFrA

performance requireluents and will substan. aren.oleworthy because they eliminate :ronny

activities in ~lexico.For some products, tially liberalize restrktiaosou financial

cho.1cesaOout wllere to locate factories this will result in, more ratlonnleconomjc

the U.S. and Canada rather tban moVinga.s fim lsa rea ble to supply Mexican markets from.

to MexicQ,tomeet local man

requltenlents~However, as in

the case of the tariff reduction schedule ufacturing

s~ lVlexico is

granted exceptions that pt"vvide longer

liberalizing provisions th::~n is tbeUnitedtime periods to comply ~vith investment

States ot Canada. This

cession reflects

~1exico"s less developed status

and relatively .more closed economycon

.

The NAFTA isa massivedocum

negotiations. It consists of five volumes.ent;tlle product of lengthy multilateral trade

of thetigreement is n.ot the final word. and nearly 2,000 pages" Nevertheless, the text

committees or working groups for furtherAlmost eve ryc hap tet calls for the fotmatiollof

clarification and administration of the

agreement.

trade

One sector in which the NAFfA

For national sovereignty reasons, Mexicodoes not HberaHzeinvestments is petroleum.

energy resources. Foreign investment willwIll maintain most of its existing re!->trictiollS on

exploration ,and development, andO.S. continue to be prohihited in petroleum

and Canadian finns will not be able to

~fexican retail gasoline mar

enter the

ket.

Unlike the U.S. - Canada Free Tra

the first major trad e agreement that dea de Agreement and the GA n the NAFr;-\ is

(\Veintraub). Key environmental prov ls ina significant way with tbe environment

isiol

accord on North .Amerlcan environmen lS found in the NAFT,f~text, a trilateral side

environmental dean-up initiatives, are tal issues~ and U.S. - .tYlexico border

discussed in the third section of this pape

r~

In addition toa side accord on the env

ironment, there are also side

labot issues and import surges to be

implemented by the trading partners. accords on

The side

accords supplement, but do not amend,

NAFTA.. They promote compliance withthe rights and obligations contained in the

problems before they develop into trad national laws and regulutioo5 and seek to solve

e disputes.

fna n effort to avoid a drift awa

seeksconsistt.!ucy with provisions of they from freor multilateral trading, the NAFTA

memberShip open to all countries with GATT throughout and leaves prospective new

geographic limitution. However, there

reasOns to be concerned about the treaout

tme

nt of non-member countries. First, becare

certain preferential provisions, such as

ause

effects on third ..country trade. Second,industry-specific rules of origin, may have adverse

unanlmous approval to jOin -.. does not because the trude agreement -.- which requires

spell out the application procedur(!$ or

criteria that new members would have

to meet (H'ufbauer and Schott, 1993). the

5

The NAFTA hns been. favonibly described as. the most comprehensive 'ireetrade

pact (short ofa conlman market) ever negotiated between regional trading partners, and

the first reciprocal free trade pact bet\veen a developing country and industrial coulltries

(Hufbauer and Schott, 1993)~ For tv{exi.co, it could "lock in~i rece.utecouomic reforms,

guarantee it access toe~1>ott ,markets. In the,U~S.and Canada,andb.elp It to attract

foreign cap.ital needed for modernization. For Canada, participationiu the NAFfA.

helps secure its presence and influence in U~S.aIld Ivlexicunmarkets iund in any larger

free trade area thntmight arise in the future. Finally, for the U.S., It will bemucheHsier

to conduct b!lSiness InNlexico und tbere is unexpectntion that continued gro\vthof the

~fe:dcaneconomy will provide long tenD economic n.od political benefits.

The EnvlrontnentUl Side of North American. Trade

In contrast to IheU.S .... Cannda Free Trnde Agreement" the environment was

very prominent In the NAFI::\ negotiations. The proposed entry of ~lexicol a

developing nation~ into.a trade agreement with the United States and Canada, two highly

developed. nations, raised new que.stionsabout the environmental consequences of

furtber industrlnli.zation and resource utilization. In all three countries,environmentalists

can point to serious trade·related problems that need to be solved. But, gr.eater

differences in .~fexi(;os level ·of economic development and ability to enforce laws

protecting theenvir01lt.lent directed much of the attention south.

Furthermore, the tuna.. dolpbin dispute bet\veen ~1exico and the U.S" under the

GAIT luade international trade a concern for many environmentalists wbo bad never

before thought of trade as an environmental 'issue... n.1exicochnUenged a U.S ban on

imports of ~'lexicnn tuna. The ban ,vas based on the number of dolphin incidentally

killed by ~lexican tuna fishermen. The GATT panel ruled for wfexico, in part because

the import restriction was based on the process by which the product was harvested, not

the quality ·of the product itseJf. The panel also held that the U.S. could not use

unilateral trade measures to protect animal life outside of itS territOry and stated tbat the

U.S. should have relied on less trade restrictive methods of protection such us

international agreementS and product labeling. Althvugi this ruling bas not been

implemented (because the (;.S. and i\;fe,ico were able to ff!solve the issue)., it greatly

worriesenvironmentallsts who see import restrictions based on the method of production

asa powerful tool for advancing international environmental protection (Berlin and

Lang).

·\Vbile the 'motives of a few environmentalists may huve been to block the trade

agreement, most who participated in the NAFTA debate seem. to favor a. pragmatic

approach. As a group, they are concerned that trade liberalization and economic growth

in the absence of careful planning and poUcies that correct forexternnlities and property

tights failures willincrense environmental degradation. They also recognize that a

growing economy is far more likely to raise environmental standards than a stagnant or

6

decUllingoue t and thnt successful lrade negotiations can be used to raise the .level

of

environmental protee:t.iOll nmong the tradingcQ\lntr.ies~

~!ajor problelns tl1ttt envirorunentulists put forth in the NAFri

.\ debate are

sUIIlmnrized below under faur headings or themes. Th~yare transboundary

pollution havens; health~ safety and environmental standards; and sustainablepollution;

development. TIlere is also a brief discussion of how illterest groups tookenvirol'Jm

entul

issues to the NArl

i\ bargaini.ng table.

TransbounduQ:Pollution

U.s . .,. Canadian environmental prdblem.s are numerous and persist

but they

are dwarfed by tbe poor Hving conditions along tbeU.S.- lV!exico 'border* ent,

III 1990. an

l\merican :rvfeciical Assoeintiongroup described parts of the U.S. - Nlexico

border

virtual cesspool ,t;tltd breeding ground for infectious diseasesi' (CouncHon Sdentif as lin

i·c

Affairs)~ P.ressingenviromnentai problems include wuterc

ontaminatiou from raw sewage

:and to:<ic wastes, air pollution caused by daily gridloekat border crassingsf degrad

of nquiferS t unregulated disposal of hazardous materials, and loss of habitat (U.s. ation

El)A).

The environmental problems of th~ U~S+ .. Nfexico border are mostly the result

of

industrlu1ization~ rapid population growth and the maquil

adoras, coupled\v"ith poor

eruQtceulent of existing regulations and grossly inadequate infrastructure

s. The

'border regio.n demonstrates what hnppens \vhen public poHcies su.cceed infacilitie

stimulating

economic growtb but fail to pro'vide the necessary environmental and public health

infrastruc.tUre

to sUpport grO\vth.

Wbile the NAFTA,. eliminates the special trade status granted to the

m.aquUadoras, industrialization alld population gro\vth are expected to continu

e on the

border as trade and investment b(lrrlers are removed. This raises serious concern

U.S. and~fe;dcnn borderco01munities do not have the governancemechnn.islns s· since

and

:financing to accommodate added strain on their environ:mental and heulth

system

s, and

have often been ignored by their federal governments (Border Environmental

Plan

Advisory Committee).

PoUutionHavcns

In the NAFfA debate, it was argued that weak environmental laws and/or la.,<

enforcement of potentially effective environmental laws would provide an incenti

ve for

businesses to relocate to ~Iexico .... a pollution huven

to avoid tougher laws and

higher pollution control costs in the United States and Canada. Because

the

possibility of business relocation and attendant loss of jobs to w1exico, theofpolluti

haven fear created an opportunity fora-coalition bet\veen some envlrollmenta on

U.S. and Canadian labor groups threatened by lower wages in Mexico. It waslists and

also

ll

II

...

7

argued tIltH business relocation would both destroy tlle:environmetlt in Mexico and

ulldercut political support for tough environmental standards .in the U.S. and Canada.

T.hequestion;of whetber businessre1Qcutio,U is likely tooccut under the NAI~A

solely because countries have differingenviromnentnl standards and levels of

enforcement 1s problematic. A. 1991 study by the JJnlted StatesOovernment Accounting

Office found that during a three yenrperiod between 11 and 28 furniture manufactu.rers

in the .Los .Angeles 'area relocated all or part of tbeirmanufuctu.ring operations to

Nfexico (Hutbauerand Schott, !99a). These nmnufucturers cited "the lligh cost for

workers' compensation insurance and wages and the F.mngentair pollution. emission

control standarcls\! 11$ major factors in tllcir decision to relocate. It husalso been

reported that c.e.ttuin copper smelters, petroleum refineries.~ asbestos plants alld ferroalloy

plants have heenconstructed abroad rather than in the United States for environmental

reasons (Olobennnn).

f

Nevertheless other studies show that for many production processes,

environmental costs are only a small fraction of the ftrmts tOtal expenses and that

historically, environmental factors have not been a major determInant in. how companies

allocate tbefrinvcstments among countries (Pearson). FinnJly, evidence was presented

showing tbat the business relocation criticism of the NAFTA was likely to be overstated

in light of the SOldll share of costs inmost industries due to pollution abatement and the

already low level of Li.S. tariffs in industries facing higb pollution abatement costs

(Office of the U.S. Trade Representative).

t

f

Health,. Sarety and En'ironmental Standards

Environmentalists were cQncerned that theenvironm.entnl and health product

standards of the trading partner with the highest standards would be challenged as

protectionist measures by a partner\'Vith lower standards, or voluntarily reduced to

hannonize them with the stnndnrdsof the other countries. For instance, n stringent C.S.

food quality standard applied to Dtlexican vegetables or Canadian fruit at the borden~

could becbaUenged either as a disguised burrier to trade" or bargained away by

government offidals in an effort to harmoni.ze standard. This is a significant concern for

at least three reasons. First, scientists and governments do not agree on acceptable

levels of e~:posure to many chemlcn.ls~making it possible to argue that u. ~tnndnrd does

not have a sound scientific basis. Second, producers in a count.ry with higher standards

willargu.e that they are at a competitive disadvantage relutiveto other producers. And.

third, individual states and localities in all three NAFTA countries may sel standards

stricter than their federal. governments, whkhmight be challenged as impediments to

trade .

.Nfovi.ug beyond product standards that are applied to goods as they cross the

border, some environmentalists cnHed for the application of process standurds to monitor

the ways in which good are produced and investmentsnre made .in the three countries8

Such process standards are notco.mtnonly

specified intrndeagreements.Proponents

nrgue that high process standards are nee

ded

weaker process standards., or their ItL~enro to ptotecttheenvironment and that

rceme.nt, are objectionable .sub

sidies.

Opponents ..",which include environmentalis

ts ..... t\Jgue the case fOf.:nutional sov~reignty

in setting and enforcing processstandn

rds.:especially when t~e pollution imp

Strictly 10co.1. In their view, local polluti

act is

according to lhnetables that reflect diff on problems should be handled dom.estic:ally!

erences in incctne, social preferences, and

cnpncities to absorb pollution.

Challenges to standards affectin

dispute resolution processes in the tradg trade are curried out through consultation :~l1d

e agree.ment. In the NAFrA~enviromnenta

sought to open these processes to pubUcp

l1sts

in dispute resolution hearings on. bebalf nrticipationand sought the right to intervene

They reason increased public purticipatioof health, sufety and environmental standards.

environmental and other sodal interest u will make the proce.edings more responsive to

s. In the U.S. and C{lnada~ state and pro

governments also joined environmentalis

ts in seeking to participate In internationvindnl

ptoce~dings that would settle

al

disputes involving their own laws.

Although not technically u NAFTA issu

et the tunn..do}phin dispute under the

Gf'\TT appears particularly ominous toen

viron.mentulists~ Concern aris

es beCtlUse in

decid.ingagainsta provision of the U~S.

Nlurine Nlammal Protecdon Act "the

equated industrial methods of produc

panel

considered restrictions on taking on tion to the 'taking' of species and because it

equivalent of objecting tn '(1 protectedtbe high seas outside a natiOll~s ter.ritory as the

method of production\vithin a. nation~

(Berlin and Lang). ~fany environmen

territory"

talis

should distinguish bet\veen Hving things ts argue that the application of standards

... fish. \vndUfe~ and plants .... ~\nd industr

goods. They also believe that a nati

ial

ons

met by all domestic and foreign produc stnndardsaimed at pre~er'wing spedes should be

ers as purt of the price of admission to

market.

the

Sustainable De\lelopment

The bn)adest concern raised bv

economic growth resulting from the ~i\environmentalists was the feur that ttdditionul

pennanent harm to the worlds environ FTA may not be sustainable~insteudcau.sing

and investment ure removed~ it is argu ment and natural resonrces. As barriers to trade

ed that increased resource utilization. pro

and ~onsumption will stru.in the environ

ductit,n

damage, but also through adverse glob ment not only tllnlugh local and transborder

al impacts such as climate change. ozo

depletion. and loss of biological diversity

ne

.

Some sustainable development advocates

apposed the NAFTA based on their

conviction that tbe world has already renc

hed

the

l/linlits of growth and that further

econoolic growth will increase environulen

tnl

<!ost

:;,

fuster than benefits (Duly).

other sustainable development advocates

support trade liheralization to achieve Yet,

,~re

'f

uter

9

effic.iency in the use of resources Ul1.d believe that econom.ic growth is computiblewith

sustainable development.·nlcyargue fot polidestointe.rnalizeenvironmentalcostsulld

recognize that protectionism oftencontdbutes t.o poverty :mdabuse of the environment

(NHkeseU, Hudson).

RoleQf Environmental Interest Groups

From. eady 1990 to the fnll of 199.3, cllvirontuentaIistsio all three countries took

these problems and others to their elected officials, to the NAFTA trade negotiating

teams, and to the public. Sometimes environmental concerns and recommendations

were delivered througb coalition efforts. On other occasions,environmentaUsts acted

independently,

In the United States, the Bush Adminlstrution's need to secure anextenslorl of

fast track negotiating authority from. Congress in the Spring of 1991, provided a major

oppo.(tunity for environmentalists to press for inClusion of envixonmentallneasures in the

NAFTA and related agreements. \Vorking with supporters in the U.S, Congress!> they

succeeded in convincing the Administration to add envuonmental representatives to

several NAFTA review committees~ The Administration aJsocommitted to work jointly

with Nfexico to carry out a "paral.lel planll to improve public health and the environment

along the border.

During the negotiati<..1 of the NAFfA, environmentaUsts participated in

legislative and administrative hearings and numerous conferences. They also met.

regularly wi.th trade negotiators and elected officials in all threecountdes. TIle final text

of the trade agreement responded, with varying degrees of success, to some of the

environmentalist!,' concerns.

In septembe r 1992, Presidents Bush and Salinas de Gortari and Prime Minister

Nfulroney signed the NAfTj-\' However, the U.S. Congress did Jj~)t pass the legiSlation

needed to impiement the NAFTA until November 1993; more tbt~n one yenrafter

President Clintons election. During his cumpaign~ :Nlr. Clinton assured Nlexico and

Ca.nada that he would not seek to renegotiate the N;\FTAS text. He did however. cull

for trilateral side accords on theenvirorunent and labor.

t

Prior to net otiatiug the environmental side accord~ the new Clinton

Administration sought rewmmendations from a brond range of experts .in environmental

groups, business, academia and govrrrunent. Se~.'eralenvirorunental interest groups thut

ultimately supported the NAFT.\ worked together in 11 loose coalition. to develop

detailed proposals on enforcement1 regiontl1 cooperatioD" and U.S.• 1vlexko border

fu.nding. As provisions responding to envirolUnentnl concerns becrune dear in the side

accord negotiations and in developing plans to help cleanup the U.S... ivlexico border

region, theenvironmel1t became less of an issue in the remaining nlonths of the debate.

10

By the fall of 1993, nearly aU environmental groups in Nlexico strongly supported

the NAFfA, while urging their governnlent to continue strcllgthening its environmental

pr0grnnls. In Canada; most environmental groups opposed ttie NAFfA raising many of

the fears that had first surfaced in the U.S."Canada Free Trade Agreenlellt. And, in the

U.S., the major cuvirollDlental groups. split due to differences of opinion concerning the

NAFl~) text, the adequacy of governm.ent fuudillg1 and the likelihood of renegotiadon.

To increase their political strength. the allti. .NAFTA environmentalists joined with a

group of antl",:grO\vth advocates, traditional protectionistsnnd conservatives already

working against the trade agreement.

Now that some time bas passed and the NAFfA is beingimplernented, there is

evidence of a significant split in the North Amedcanenvironmentai community.

Environmentalist from both the pro-NAFli\. and anti-NAFTA ca~.t)s and from all three

countries are~ once again, w()tkil"g together on issues of luutual Interest and disagreeing

on others.

00

Solving 'fhe Problems

Co.nfronted \vith a series of environmental problems that could not be ignored,

policy officials and trade negotiators sought a strategy to successfully integrate trade and

environmental objectives. The results of their work are found in several provisions in

the NAFTAS text; in a trilateral side accord, called the North American Agreement on

Environmental Cooperation; and in environmental c1ean~up plans for the U.S. "" ~·fe.'{ico

border region.

These new commitments are explained and briefly evaluated in this section. In

some cases, they create rules for policy coordination and problem solving. In other

cases, they merely declare the intentions of the countries to pursue a particular course of

action.

NAFTA's EuvironmentnlProvisious

The NAFTA explicitly deals with environmental issues in its Preamble and In flve

chapters: international environmental agreements (Chapter One), sanitary and

pbytosanitary measures (Chapter Seven, Section B), standards-related measures (Chapter

Nine), investment (Chapter Eleven), and dispute resolution (Chapter Twenty). Key

environmental provisions of the NAFTA are summarized in Table 2.

These provisions attempt to resolve trade and environment conflicts that relate

directly to the trade agree.ment. They include! potential conflicts bet\veen the trade

agreement and trade measures in internath.. ual environmental treaties; the need to

discourage product standards that Ure disguised barriers to trade while protecting

stanuards\\!ith legitimate environmental purposes; and the risk that liberalized trade and

11

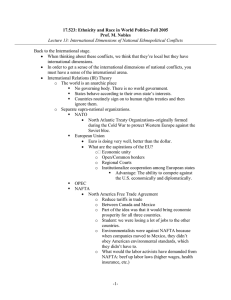

TnbIe2:

Key Environmental Provisions

or the North American Free Tradl.! Agreement

Chapter One (Objectives) gives precedence to confiictlng trade provisions

in three international environmental treaties.

*'

Chapter Seven, Sectio'o' B (Samtaryand Phytosanitary measures) and

Chapter Nine (Standaros ..Related :measures) concern product standards.

Eacbcouutry may set its 0\\11 appropriate levels of protection" Under

Chapter Nine, noo:ordiscriminatory general standards are essentia.lly immune

from challenge if they have a I'legitimate purposell such as protection of the

environment or health. Surutaryand Pbyto5unitary 'measures must meet

further tests. such as having some scientific bnsis. Effons to harmonize

either type of standard must not lower the level of protection.

Chapter Eleven (Invesunent) seeks to discourage a country from rela.!ing

hs environmental standards, or their enforcement, in order to attract

investment.

Chapter 20 (Dispute Resolution) allows dispute panels to consult outside

scientific or environmental experts and to create scien.tific review boards,

subject to the approval of the disputing countries.

Source: North American Free Trade Agreement, 1993.•

12

investulent provisions wllilead to pollution havens. The :mo.in sourceofcon.flict in these

provisIons is betweett, tr::lde UberalizationandenvirOD.mental protection, but nat:onal

sQver'!igntyis also a significant is?ue,especiaUy for product standards.

International Environmental Agreenlents

~~A:FTi'\S Article 104 gives precedence to ,ordllcting trade proV'i!.lOl1S in three

.internntional envirol"411ental treaties. T:uevare: the Basel Conventl.urt on Control of

Trnusboundnry ~/fovement5 of Hazardnus '\Yastes, the r..fontrenl Protocol on Substances

th~t Deplete theOZOt1C t.uyerJand the ConvenUonoll the International Trade:in

Endangered Species.. Other treaties may be added by agreement of the panies.

'Coder the GATr~ there is un eX'Plicit ba.~b forre~olvingcoufljcts between tile

trade agreement and environmental treuties. For example, the Basel Convention

probibit~ signatories frottt exporting hnzutdous wasta to non ..signutories. If a signatory

\\+erechnllenged under the GATT for refusing stIch exports, it could not rely on the

Basel Convention because there is no CATT provision consitieringtbe effect of

inconsistent environmental treaty provisions. It could only rely on theGKITs Article

XXexceptions,which'wQuld leuye tbe nutcome highly uncertain. flowever,under

Ardcle 104~ the Basei Convention would take precedence to the extent of any

inconsistency \vim NAFTA'S trade rules. Trade sensitivity in Article 104 is found in the

requirement tP "t where a party has a choice among lie qu aUy effective and reasonably

avanable~'means of .meeting itsenvironmettml treatyobligations,it mustclloose the

rneHUS that is least inconsistent with the NAFtAS trade rules.

The NAFTA is the first trnde ugreement to give such precedence to

envlronmentaltreati.es. Environmentalists are concerned, however, that the countries

will not act quickly to include :additional treaties that .may conflict \\tith the NAFrA

The requirement calling for the selection of the least NA,F1:>\.. iTlcon."iist~,,;nt means of

honorlngenvironmental treatyoblignnons i~a reasonable concession, as long as it is not

interpreted to aUow second-guessing of a countrys selection.

Product Standards

One of the m.ost complex issues is the us~ of product stundttrds to limit the import

of goods that may be harmful to health, safety and the environment The NAFTA~s

provisions provide more protection to ncotlntry's envirorunental standurdsthen either

the existing or proposed GATt text The NAFTA does this by (1) making the criteria

for defending challenges more deferen.tial to environmental measures: (2) giving dispu'ie

p.anels access to environmento.lexpertise; and (3) prohibiting dovy'llwurd barnlOnization

when the parties cooperate to make their standards compatible.

Criteria for Defe.nding Challenges to Standards. Tbe primary function of

standards pro'visions inn trade agreement Is to root out disguised harriers to trade. TIle

13

t-V\I~)\ balances thu~ fuuJ:tion ngninst the .need to shield Iegitimateenvironmenud

m.e.as~Jres. Tbe texteulpl.oys differentcdterla dependi.ng Oll whether the product

standard .is n, sanlturY'undpbytosanitary (S&l')standu.rd(which deals. with the tisksof

contilDlinants in f()Qdand the spreader disease and pests) 'otagcnerttl product standard

(\vhkh includes all other l~nvironmental product standards, such :a5 lh(,se regulatillg

.Uli.nimum flleleconoIl1), .and 'pollution emissionsot: autouiobiles). S&P smndardsnre

subject to' stricter scrutiny bemuse tbey have traditionally been mo,re nbused. for

protectionist purposes.. Howeve~,botbtypesof standards enjoy It gene.r::d presumption of

NAFl'k\cOlllpatibUity if they are ba«,ed :upon international standards. suell as tho~e ·or

the Codex Alinle.nnuius. Thus. tbe following discussion considers the defense ofa

standard that exceeds, interna.1J(loal nol1llS.

Fo,r botbt;ypesof standardst the N}\FrA shifts the burden ·of proof from the party

defending the standard (at) is the case under the GA1'T) 10 the challengin;g party"This

meanstha.tlf the dispute pan,!lun.ds tbeevidence inconclusive. itmu!\t uphold the

standard... Second. acbnllenged partyc:m elect to hnve the dispute decided sc:1ely under

tbe NAFTA. ThIs 'Prevents ·a country: tbat is ~balletlging ~, standard from .avoid.i,ng the

provisions of the NAFfA, by bonging tbechaUenge under the GAD:

The NAFTAexptfcitlyaU()ws euebparty loseti.ts own appropriate levels of

protection. or levels ,of risk (i.e~oneca.~e ,of C'nm~er in a million caused by pesticides in

fruit) And. to achieve thut level ·of protection byemplO,ying standards tbutexceed

international norms (Articles 702, 904.2t '905.l)~ TheNAFfA does. bowever:. impmi.e

trade disciplin,e On. how the level of protection is chosen. For example.. the parties are to

avoidnrbitrnryand unjustifiable distinctions between s'iulilar goods or levels of protection

where such distinctions discrimiIlnteagainst the goods of another part}' or aet as a

disguised barrier to trade .(..o\rtlcles 715(3) and901(:Z».>

The rnajar d.ifference between tbe Nt\Ff}\:s treatment of the two type~ of

standards is tbat acountrys general standards huving a *tlegitimate objectl\+e'· dono.t h~l\'e

to meet further tests that nreapphed to S&P standards. A ntln..di.scriminatory genet'at

standard isessentiaIly immune if .its demonstrable purpose is to achieve a tflegitin131e

ubjective1!'t such as protection of the environment, health~ sufety or sustainable

development (Articles 904(1},,91S). Thus1 for exalllple, if Canada sought to reduce

greenhouse gust.missions by requiring that new cars obtained a. certain le\rel of fuel

economy~ it would be ·"irtuaUyimpos'Sible fJrthel:S or ~lexico to successfully challenge

the stundard if it were applied equruly to both domesticund lhreign cars.

An S&P standard, (lO the l,1ther hand, is subject to several tests. For ex~rmple''\ the

standar'dmayollly beuppUed to the extent neces$,ary to tlchieve the chosen !evclof

protection fArticle 712.5) . TIle NArlA negotiator~ specIfically rejected the current

OA17 ,requirement that the party must chonse the S&Pmeasure that is ttlenst restdctilfe

to trade." The challenged party need only show that .its chosen level of protection

necessitates wemeasurc, it need not counter claims that the fiame h~\el of protection

14

could beacllieved by ,ll Jess trade disruptive meaus, such, as lnbeling or .0. pollution ttLtw

The pivotnltenll I'necessnry~'i howevett lsnot: derined in the text.

Au S&l?meusuremust also hnve a scientifi.c ba!sls. The NAFI'A test requires

only the existence of some scientificevidenee supporting tbe measure (Artic1~s 712.3,

and 724). Thus, the challenged party need not engage in a battle of scientific e.xpertsar

evidence.

FrO'ffi the environmental perspective, the NAFTA standards provisions. are a

significant im.provem,ent over those In the GATI: particularly with respect to general

standards. &10$t environment.alists would have preferred stronger and clearer protection

for S&P standards,. such 'as ,a cludtication of the 1fnecessart test.

Dispute .Resolution, The NAFTA gives panels deciding ch.dlenges to stund1lrds

the opportunity to seekenvirorunentalexpertis.ein resolving disputes. Theycnncollsult

with outside environmental and scientific experts orcreute scientific review boards,

subject to veto by the disputing parties., These provisions partiaUy respond to the

concern that dispute panels would pass judgment one.nvironmental st~lndards t~vithout

unde.rstanding scientific issues crucial to the dispute.

En\iironme.nralists would have preferred greater access to scientific expertise, but

their main criticism is that the NA.FI:AS text does not Increase the tra.nsparency of,and

puhlicaccess to~ trade, disputes involving standards.

Harmonization. High product standards are also threatened by the parties'effoTtS

to harmonize their divergent standards. The N~A, however~ prevents "dO\vuward

harmonization by requiring that any harmonization beaccompllsbed v.1tbout lowering

the level of protection (Art. 755(1), 756, 906(2). For general standards, the parties also

agree to work jointly to enhance the level ofenvirontnental protection (Article 90G(

These provisions are a significant improvement over the GATT: which contains no such

safeguards (Cbarnovitzj.

11

1».

Investment

The NAFrA text discourages the countries from lowering environmental

stlndards for the purpose of gaining business investments. It states that it is

"inappropriate" to use relaxed environmental regulations or enforce.ment to uttruct

investment and 'admonishes that a country "should not" undertake such an action (Article

1114) A country may request a consultation \vitl:a trading partner, if it believes that

the partner has ignored the guideline.

EnvironmentaUstsare dissatisfied that this provision does not prohibit the

relaxation of standards andthut it merely culls forconsultntion. Inndditioo, the .text

15

only addresses a portioner: fhe pollution ;haven problem. It does not confront existing

1#1.'( controls or (he rela.,,<ationo.f standards :(or thebeoefitof domestic industry ratber

tban foreign invt:'stors. Fortunately, the environmental :sldeaccord responds nlore

broadly to these concerns and provides tools fordeallng with lax enforcement.

Th~

North ,American Agreement on E'nvironmental Co.opernUon

\Vhile the envirO.runentnl prov:isionsof tl1e NAITA:<l text focus on issues closely

related to the trade agree,ment, the sidenccord. estnblishesa framework for cooperation

on,environmentnl matters and commits the parties to effective enforcem.ento£ their

environmentnllaws{Notth American Agreement on Environmental Co op etation). Key

provisions of tbe. side accord are summarized in Ta.ble 3 and discussed below. ~{any of

tbe conflicts dealt wit.bin theenvironm.entul side accord .ate not between environmental

protection and trade liberalization, but bet\veen environmental protection and national

sovereignty~

Commission on Environmental Cooperation

The heart of the environmental side ;uccord isa Co mmlssio n on Environmental

Cooperation« Its functions include fostering cooperation and solving environmental

problems before they become trade disputes; conducting research and making

recommendations on complex issues sucha.c; the use ·of process standards; and providing

environm.entalexpertise to various committees created under the NAFrA. The

Commission will also resolve specific complaints by citizens and countries that a country

15 not effectively enforcing its environmental laws.

The Conunlssion is directed bya Council of the environmental ministers of the

threecountnes The work of the Commission\vi.U be carried out by a Secretariat 'Witb

advice from a tdnational public advisory committee ·includingenvironmentalists.

fc

Enforce.ment of Environmental La\VIi

The side accord includes specific provisions for promoting theenrorcement ·of

each country's envirOllmentallaws. The ComlrJ.ssion accompUshes this by examining

complaints about la.xenforcement from individual citizens, interest groups and countries

and. by requiring the accused party to respond in. an appropriate lUanner~

The ,enforcement mechanism, has varying degrees of Commission Involvement.

ranging from simply asking a party to respond toa citizen's complaint to formal dispute

panel proceedings between countries that can lead to fines and trade sanctions. A~ the

level of Commission involvement and potential intrusion upon national sovereignty

increases, so do the requirements for what may be considered and the opportunities for

negotiated solutions.

16

Table 3:

*

KeyPto\'isions ·of the North American

Agreement on. Environmental Cooperation

Creates a Commission on Enviro.nmental Cooperation to facilitate

cooperation and research on problems concerdng trade and the

environrnentnnd tbe North American env'rOl1m.ent. TheColnmission may

develop recommendations on issues such ,{5 process standards and common

emission limits for certain pullutants.

Establishes a framework to promote .effecti\ie enforcement of each

countrys domestic environmental laws through citizen complaints to the

Commission, consultations and disputes bet\veen the parties.

CommitS the countries to provide for public participation in domestic

environmental decision- making and enforcem.ent.

Source: North Ame.rican Agreement on Environmental Cooperation 1993.

t

17

At the initial stage, any .citize Itenvironmentul group or other entity ofacountry

may complain to the Conunission that any NAFfAcountry has failed to effectively

enforce its environmental laws. Recognizing that ~no country is able to enforce .all of its

enviromnental1aws cOlllpletel>~ the .text defines ~Ie£rectivee;uorcetnenel and takes

account of the allocation of scarce resources an1ongenforce.::.ent priorities. If a

complaint ,meets basicrequire.ments, the Commission may require the country to respond

to the allegation. At this point there 'is no requ.irement that the allegation of lax

enforce.tllent be specifically related lotrade. Depending on the country>s response to. the

complaint, the Secretariat may prepare a factual record with the approval of two..;thirds

of theenviromnentallninisters (Articles 14..15).

Formal con.sult··~tions between the countries and dispute panel proceedings may be

requested only bya -countrj. The country seeking consultation must allege a "persistent

pattem"of lax enforcement. If consultations faiJ, a dispute panel may be convened.

However, tbis requires two .. thirds approval by the Council and evidence that the la."{

enforcement affects trade betwe.en thecountnes(Articles 22-24). If the panel finds a

pattern, of la"<: enforcem.ent, an action plan is prepared to remedy the problem. Ira

country fails to follow the action plan; the panel wiUlmpose fines which are backed up

elther by trade sanctions in the U.S~and Mexico, Or domestic court proceedings in

Canada. to collect the fine. The amount oftbe fine, up to S.20 million, is based on

factOrs such as the extent of the enforcement failure and the country's effort to remedy

it. Reve.uues from the fines ·are to be useu,at the directio.n of the Coun.cil. to improve

theenvironrnent or environmental enforcement of the country paying the fine {Articles

34-36, Annex 34)t

Some envirorunentaHsts .are satisfied with this enforcement mechanism~

parJ.cularlythe direct access of citizens to the Commission and the threat of sanctions

against recalcitrant parties. However, critics complain that the schem.e is too

cumbersome; that the many checks and balances will greatly delay the imposition of

penalties.

Strengthening Public Participation

The side accord includes severnI important commitments by the countries to

increase public partic.pation in domestic enforcement and in decision-making relating to

the environme.nt and pubhc health. For example, they agree to ensure that their citizens

have tlapprcpriate access to judicial or administrative proceedings for the enforce'ment of

environmental1aws. The countries also agree, to the extent possible, to give advance

notice of proposed laws and regulations, and to provide an opportunIty for comments by

interested persons.

..

ll

These commitments reflect a belief that lone t~Jnl integration of envirorunental

policy requires giving the citize11s of each country ready :~cces; to ehvironmental

18

.infOtrnation~decislon

lllakillga.lld remedies. Such participation lUqy lessen the need for

the Commission to act nsawatchdog.

The environtnenttd side ,accord containstnuch of ,vhnt cllvironnlcntalists had

proposed. Some hnvectilicized the Hll1its on the independence ·of theCownnssl.onnnd

ltsfuncdolls·. 'However, tbis was deem.ednec.essury bec:nuse of potential intrusion on

national sovereeignty and the need for tbis experimentnllnstitution to have flexibIlity to

evolve.

U.S.-iVlcXlcOBQrder 'Environmental Initiatives

The introduction of U.S... ~texjco borderenvironID.entnl problellls into the

NAFTA debate focused pOliticnlnttentiollon. long. ..oeglcctedneeds in, hothcountries. It

was seen as an opportunity t.o raise public conscinusness about the border region. aod to

redress lts degradation. Me.w initiatives. to deal with these needs are being carried out

under existing bilateral agreem.eot5 and nre llOt formally tied to the NAFTA. However,

in. both countries, the initiatives were proposed to win support for the trade ngt~eement.

Threeexnmples of ~lparanerl efforts. to solve public health 'and enmronm.ental

problems ,along the U.S. - 1vlexico border are described below. Tbeseefforts help border

resIdents sbape prioriti.es for their co mmuni.ti es. commit the federal governments to more

environmentnlinfrastructure investments, and increase private sector responsibility

through user fees and proper~y right:. strategies.

First! the U.S. and ~fexico worked together to prepare a multi-year ~nvironmental

manag.em.ent plan for the border region {U.S. EPA). The .firstcotnponent of the plan

(for 1992. .94) was released in FebnlD.ry 1992. The new plan is important because it

caused the two countries to identify joint problems, to set priorities, and to allocate

federal and state monies for public lnfrastru.cture facilities in. the region. For example,

the U.S. and !vfexi.co promised an addi.tional $700 millionroostly [or municipal

waste\\"uter treatment during the first phase of the plan (Congressional Budget Office).

However, the border plan. bas been widely criticized for being vngueand unresponsive to

local r;eeds, ,and because it provides neither the gove.rnauce mechanisn1s nor the funding

needed to ~ f)lve :nany of the region's problems (Kelly). Bothcountrles have recently

committed to prepareantlimproved" border plan and to locate environmental protection

offices in tb~' burder reglo,n (Browner).

Second~ in respon~e to continuing criticisms, theU~S. nnd ~lexico agreed last

November to create two new binational institutions to facilitate border en'Viroumentul

clean..up (Agre(~m.ent ()f November 15, 199.3). A Border Environmental Cooperation

Commission wiUassist local com,tnunities in coordinating and designingenviroumental

infrastructure projects and in conducting environmental assessments of proposed projects.

NIechanisms \\till be se: up to ensure that the priorities of affected communities and

19

members of tbe,pubIicaretaken into account. The b()rder cOtllllu5sion will be directed

by a binational board and u.citizenndvisory 'council.

Projects approved by the bord~r comrnissionwill be sent toa North American

Development Brulk for possible financing. TIle bank will be in.itinted with cnslland ,loan

guarantees contdbuted oqually by theIJ.S. and Mexican governments. Federal funding

will; 1n ttlrn" be used :to leverage larger amounts of '!lloney by requiring that projects be

co.,financ:ed by state and local governments and through user fees paid by prlvatefirrns.

It 1s e~:pected that the bank will provide an increase ·of $2 to $3 bHli~n itt financing to

th;;; border region over the next ten years (Agree.mellto£' November 1.5, 1993). The bank

will also be directed bya hinational board.

Fina.lly; the MArry.A debate has spurreJefforts to develop new bi.national

governance institutions to solve loeaUzedtrans~oundary pollution problems. For

e.xample~ the possibility of increusedecooQmic growth and. further environmentul

degradation under :tbe NAFfA 'btt.<; caused the U.S... ~fexico border cities of EI Paso,

Texas, anded. Juarez, Chibuabua~ to recognize the need forregfonal instituti.ons to deol

with eUviroumental quality. Because of tbe COIbbined effects of their im.mediute

proximity ina high elevation, arid mountain valley, and because of rapid populationund

industrial growth related tointemational trade., the t'sister citles share a very serious air

pollution problem. Healthy air quality standards are regularly violated in thecomm.on

airsbed that serveS both El Paso and Cd. Juarez.

tl

To reduce air pollution! community le.uders have agreed to workcoopera,tively to

create an international rur quality management district encompassing tbe two cities and

their surrounding area (Pnsztor). The management district will monitor air quality,

inventory emissions fromruajor sourcest Set air quality goals, and administetincentive..

based 'mechanisms for achieving these goals. Businesses operating in theairshed \viJl he

allowed to decide where and how to make their required reductions in poHutionand wlll

have an opportunity to earn emission reduction credits that may be traded or banked for

future use.

The international air quality management district provides a g(werno.nce tool

needed to address transboundaryair P()Uution. Withol-it joint management. national

clean air legislation in either country is unlikely to solve the poUution problern and

would not do soiP the most efficient manner possible. Alloyving new ande.:'~.'panding

businesses to make investments in. pollution offsets and to earn emission reduction

credits throughout the airshed helps to insure that additional economic growth due to the

NAFl}\ wiU contribute to the process of cleaning up the nlr.

One practical consequence of cross·border pollution transactions is that U.S.

businesses in bigher..income HI Paso t where many pollution abatement investments have

already been mnde, ~ill huvean 'incentive to invest in lower..income en. Junrez where

fewer pollutiona'batement investments have been made and large reductions in pollution

t

:0

nre possihle~ Inndditiou; 5uppliersof clean technology andulternative fuels may enter

the market to help finance these cross.. borderinvestments inexchallge fora share of the

emission reduction credits that .are.generated.

Ule :internatiomllait qualitymallugement district .... anenvi:ronmental. poUcy tool··

.. will benefit international trade by 'ptoviding an. efficient means of achIeving healthy air

quality needed t<) sustaine>.:panded trade and ecouo.rnlC growth. Trade liberalization

thrO\lgh the NAFrA on the other hand, will benefit the environment by eliminating

tariffs and other restrictions on tbeexportof polludonconttol equipment and technical

services.. These complementary outcomes,. which depend on theac.ceptanceof com.mon

air quaUty goals and business strategies tbat transfer poJiution-reduciog tecbnolo!''Yt will

benefit 'El Paso and Cd. Juarez by .improving their environmental performance and tbeir

opportunities for future economic growth.

\Vbere Do Thlngs Go From Here?

The NAFfA negotiations demonstrate that it. is possible to v..rrite a comprehensive

trade agreement v;dth environmental provisions and to l1Hlke relatedenvirontll.ental

commitments without subverting important goals of trade and investment libernlization.

This outcome refie<:ts n high degree of interdependence among the three countries. It is

the latest step in a series of bilateral agreements and unilateral decisions .,.- 5tarting in

the 1910s ... that move toward a more open trading systelu in North America.

The particular reconciliation of trade and environment issues found in. the

NAFrA was heavily influenced by environruentalists. Howevert it does not dictate

tmifoIlIlity of standards or otherwise impinge greatly on a nation'S sovereign control over

environmental matters within its own borders. .Policy officials and trade negotiators were

able to succeed because they rejected the view that conflicts behveen trade Uberalization

and environmental protection are insurmountable,and accepted the challenge of tr'/ing

to figure out how to achieve both goals.

TIle introduction of this practical strategy into the intern.adan.ttl trade arena may

be themos! significant feature of the NAFI:-"\ in shaping whnt might happen next.

There is now a. model that recognizes each country's right to choose appropriate levels of

environmental protection. tilts toward up\vard barmoniz~ltiont gives precedence to major

international environmental treaties, and retains sufficient discipline to allow disguised

trade barriers to becbo.llenged~ In.creating a COlnmission on Environ.mental

Cooperation, the N.AFD.\ countries seek to achieve better enforcement of .existing

environmentalluws. And, over u period of tlme~ they will r.ddress process standard.s thtlt

regulate methods of production and develop more consistent environmental policies for

the region. These commitments should help the countries achieve greu.terefficiency with

respect to the environment and trade~

21

Responding to long-standing needs that were brought iuto the spotlight of public

awareness by the trade negotiations, the U.S. and ,Mexico have earmarked additional

government funding for the border region aod have taken steps to give citizens from

border communities more influence in settiog priorities and solving problems.

Trunsboundary environmental damages, such as air pollution that may be intensified by

e.x-panded trade, are dealt with through bilateral governancemecbanisms that delegate

responsibility to the priV'ate sector.

Thf. NAFrA expe.ricnccs have been taken to thcGATr negotiations where

environmentalists .raised coucernsabQut challenges to legitimate environmental laws and

are working for the creation of a Committee on Tr.ade and the Environment to insure

post. .Uroguay Round follow..up on envIronmental matters.

Trade liberalization will CO.lltlnue through regional pacts, like the NAFTA, and

within the GATT. But, it will occur in the context of a much greater focus 00

environmental issues than bas been tlle case In the past. Finding strategies to achieve

,more open trading systems and to provideeco!ogical services needed to sustain economic

growth will be a key factor in fostering greater economic and social progress in all parts

of the world.

*The authors are senior economist, Environmental Defense Fund in Austin,

Texas, and pro-bono counsel, Environmental Defense Fund in Washington, D.C.,

respectively.

22

References

Agreement Bet\veen TIle Gov¢tnment of th~tlnited Sta~merict1nang Ih~

Government ()f th\~UnitedNfexicnn StatesC~mcgruingTheEsttlbHsl1m~nt of a

.Border EnvirQnme.:1t COQperation COrt1mi~$iQnt\nd aNQl1b...A-l1~!il;:m.

DevelQpment Bank. 1993. Wnshingtou, D.C.: U~S. Departm.ent (Jf the Treasury,.

November 15.

Berlin, Kenneth and Jeffrey M. Lang. 1993. "Trnde and

\Vashingtpn Quarterlv AutunlO 16:4 pp. 35 ..5l.

theEnvir()nme.nt~"

The

Border Environmental Plan Advisory Comnrlttee. 1993. Letter to Car()l13rowner,

l~dministrator,U.S. Environnlentul Protection Agency. Contact Dr.H.elen

Ingram, Tucson, AZ: Th.e University of Arizona.

Bro\vner, Carol Nt~ 1993. Testimonv before the COlnrnittee on \VaYSandNreuns~ U.S.

House of Representati.ves. \Vashington, D.C~; U.S. Environmental Protection

Agency, September 14.

Charnovitz, Steve. 1993. "NAFTA:An Analysis of Its Emrironmental Provisions.'1

Environmental LawRepQrt~r: New$ nnd Anrllvsis. Vol X.'XIII, No.2. Washingtou

.D.C.: Environmental Law Institute. February

i

Congressional Budget Office. 1993. ;.. BudgSftnrv ;lnd EconOmic Ana '\Isis of the North

American Free Tradf: Agreement. ·Wnshington, D.C.: The Congress ("If the

United States.

Council on Scientific Affairs. 1990. APermaneot I/,S, .. ~ifexico Border EnvirpntpeotaJ

Health Q~)mmission. Chicago, Illinois: Anlerican 'Nfedicul Association~

Daly, Herman E. 1993. IlTIle Perils of Free Trade:

i

Scientifi~

i\merican. Nl)Velnb . ~r.

.

Globennan, Steven. 1992. liThe Environmental Impacts of Trade Liberalization."

NAFTA and the Environment edited by Terrv L. Anderson. San F~anc~:"(). CA:

Pacific Research Institute for Public Pdlicy. ..

.Hudson, Stewart. 199:!.i'Trade:t Environment and the Pursuit of Sustainuhle

Developnlent. In Intermnional Trade and the Environment edited by Patrick

Low. \Vnshington, D.C.: TIle 'Vodel Bank.

1J

Hutbauer, Gary Clyde and Jeffrey J. Schott. 19<)2. North American Free T(ade:

j,lnd Recon1·'1~ndations. Washington, D.C.: Institute For International

Economics.

I~\lr!'

'Hutbauer,Oary Clyde and Jeffrey Schott. 1993. NAFTA~ Art Assessment.

\Vashington. D.C.! Institute For International Econonlics.

Kelly, A-1ary Ef 1992.NAF'rA antI the ,Q,S.Lwfe.ncQ ~prder Enyjrqnment; "Qp:i(}ns, for

CQngressiQnalActiQn. Austin, Texas: Texas Center for PoHcy Studies,

September.

Krugman, Paul. 1993~ 'The Uncomfortable Truth About NAFTA;'FQreign

November.

Aff~.

NrikeseU,:Raymond F. 1993. tTbe Concept of Sustainable Development "'- ,A

Prelirtliuary Statement. l!npubUshed IYfauuscript. Eugene, Ore,gon: 'Ut'Jversity

of Oregon

1I

North American Agreement on Envl'tQmnentaICooperati0n Between The Qtwetnrnent

Qf lheUnitetl Stnte~af f\tnerican. The Government Of Canada And The

GQvernmentOf 111e United !vfexicatl$tates. 1993. l03rd Congress! 1st Session,

HOllse Document 103-160, '\Vashington,D.C.~U~S.House of Representatives.

North Arnercan Free .Trade Agreement Bet\ve~nThe .GovernrnentQf Th~Unitr.;d

States Of America, The ytNetnmentOfCanttda And The governO)f.fut Of'Ine

. United Nfexican States. 1993* l03rd Congress, 1st Session, 110use ,Document 103159, Vol.l. WashingtOll, D.C.: U.S. House of Representatives.

Office of US. Trade 'Reprcsentadvet Interagency Task Force. 199t Rgview Qf bY'S...

iVfexJco 'Environmental r~sue~.Washington, D.C.

Pasztor, Andy. 1993.!tU.S., !vrexican Officials Plan to Create Alr-l'olludon Zone for

Border Residents. The "lall Stre~t Jourom. New York, N.Y.: September 10.

tf

Peorson, Charles S. 1987. nEnvironm.ental Standardst I'ldustrial Relocation alld

PoJution ~1avens.n ;Vfultinationnl CorpQrations. Environr.1entand the Third

'!ti!.~.rld. \Vashington, D.C.: World Resources Institute

Repetto. Robert. 1993. 'Trade and Environment ~oIides: AchI.e\:~l1g

ComplementnddesandAvoidlng Conflicts:· \VRI rSSlH.~;; and 'Idem::. Wnsbington.

D.C.. \Vodd Resources Institute.

U.s. Congr 1'SSfOffice of Technology Assessment.

1992. U.S.",'Nfe7\1CO Trade: Pulling

Joftetheror PuHing Apart? ITE...545. \Vashington, D.C.: :U.S. Government

f

Printing Office.

24

u.s. Ert\1ronmenml :ProtectionAgeucy and Secretada Desarrollo Urbanoy Ecologia.

19921- IJlt~gr~t~~i Envirgnmeftttll PI,rnfQt· th~rltexicQ "U.$htiQtd~tAren

..(r::ir~t

Stage 12.2.2,.. 199·ttl*\Vnshln.gtoo, D.C.

\Veintraub, SidneYJ 1992. ~'The Nortb Anledcan Fre~Trnde Agreement n~ NegotiA

A 'U.S. Perspective/ Sellrinar Paper~ Austin Texas: The U:nivershyof '''exns.ted.

f

f