environmentally significant areas (esas) in the city of toronto

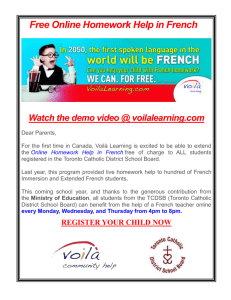

advertisement