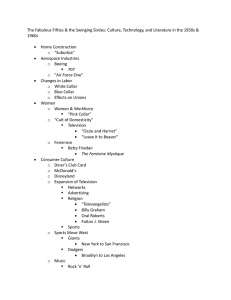

Motivation of Blue- and White-Collar Employees

advertisement