JISC e-Learning Models Desk Study Stage 2

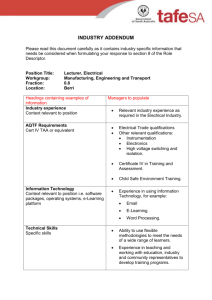

advertisement