Congestive Heart Failure Clinics: How to Make

advertisement

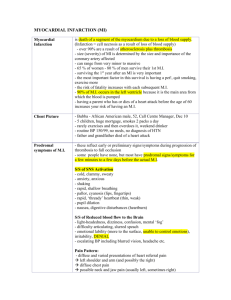

Cardiovascular Innovations and Applications Vol. 1 No. 1 (2015) 13–18 ISSN 2009-8618 DOI 10.15212/CVIA.2015.0005 Review Congestive Heart Failure Clinics: How to Make Them Work in a Community-Based Hospital ­System Joshua Larned, MD1, Mohamad Kabach, MD1, Leonardo Tamariz, MD, MPH2 and Kristine Raimondo, MSN, ARNP-BC1 Jim Moran Heart and Vascular Research Institute, Holy Cross Hospital, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA; University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, FL, USA 2 Miller School of Medicine at the University of Miami, Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Miami, FL, USA 1 Abstract Introduction: Congestive heart failure (CHF) accounts for over $32 billion in health care costs per year and is at the epicenter of health care reform. CHF remains a major cause of hospitalizations. It is known and has been reported that missed diagnosis of and missed opportunities to treat heart failure are associated with higher mortality and morbidity. CHF disease management programs have emerged as a potential solution to the CHF epidemic. The paradox remains that CHF disease management programs still cluster in tertiary hospital systems. The impact of heart failure specialists and specialty teams in community health systems is less well understood. Currently there are not enough CHF-trained teams in the community setting to address this unmet health need. Methods: We explored the impact of CHF clinics in a community-based hospital system on readmission rates, mortality, and symptomatic relief. A total of 384 patients were enrolled in the clinic between 2012 and 2015. Data collected included age, sex, type of heart failure, New York Heart Association class, ejection fraction, serum creatinine and brain natriuretic peptide values, and readmission and mortality rates within 30 days, 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year. We also compared readmission rates between patients who were followed up in the CHF clinic versus those who were not seen in the CHF clinic. Results: A statistically significant difference was demonstrated in readmission rates between patients who were ­followed up in the CHF clinic versus those who did not visit the CHF clinic for up to 1 year of follow-up. Conclusion: CHF community hospital clinics that use a rapid and frequent follow-up format with CHF-trained teams effectively reduce rehospitalization rates up to 1 year. Keywords: congestive heart failure; community-based hospital system; clinic; multidisciplinary Introduction Correspondence: Joshua M. Larned, MD, FACC, ­Assistant Professor of Medicine, Medical Director, Heart Failure Services, Holy Cross Hospital, University of ­Miami Miller School of Medicine/Holy Cross Hospital, 4725 North Federal Highway, Suite 401, Fort Lauderdale, FL 33308, USA, Tel.: +954-772-2136, Fax: +954-772-7156, E-mail: Joshua.Larned@holy-cross.com © 2015 Cardiovascular Innovations and Applications Congestive heart failure (CHF) is a complex medical syndrome that affects more than five million people in the United States alone [1]. More than 500,000 new diagnoses are made each year in the United States. This number is projected to increase because of an aging population and better care of 14 J. Larned et al., Congestive Heart Failure Clinics the ­comorbid conditions that cause CHF [2]. Despite advances in medical therapy, half of all people who develop CHF will die within 5 years of their initial diagnosis [1]. CHF accounts for more than $32 billion in health care costs per year and is at the epicenter of health care reform [2]. Although this staggeringly high figure includes hospitalizations, outpatient medical encounters, medications, and devices, it does not fully account for less measurable effects such as missed days of work, missed family days of work, and other community/biopsychosocial impacts. Despite standardized CHF therapy and management guidelines [3], CHF remains a major cause of hospitalizations [4]. The overall rate of CHF hospitalizations did not change significantly from 2000 to 2010 although the risk of hospitalization increases according to increasing age [4]. As there are far more community hospitals than tertiary hospitals, CHF hospitalizations have disproportional consequences in community health systems; yet community health systems remain underequipped to address the complex needs of CHF patients. The paradox remains that CHF disease management programs still cluster in tertiary hospital systems. Ironically, CHF educational pathways, including fellowship programs and board certification pathways, focus on advanced therapies such as transplant and device therapy rather than disease management, prevention, and new target therapies. There are numerous factors that complicate CHF care, including delayed diagnosis, inadequate treatment, inadequate education, and ineffective transitions of care. It should come as no surprise that 24% of all CHF patients are likely to be readmitted to a hospital within 30 days [5]. A sobering fact is that health systems have struggled to reduce readmission rates and readmission penalties irrespective of a patient’s socioeconomic status [6]. CHF disease management programs have emerged as a potential solution to the CHF epidemic [7]. There are some data that demonstrate that specialized heart failure clinics result in better management of patient behavior and medication adherence, with fewer hospitalizations [7–10]. Meta-analyses of CHF disease management programs, however, have demonstrated variable impact on CHF populations [11]. This heterogeneity may be explained by a lack of a standardized multidisciplinary process and variable levels of provider training and care delivery [12, 13]. It is known and has been reported that missed diagnosis of and missed opportunities to treat CHF are associated with higher mortality and morbidity [14, 15]. The transition from inpatient to outpatient care can be an especially vulnerable period because of the progressive nature of the disease state, complex medical regimens, the large number of comorbid conditions, and the multiple clinicians who may be involved [16–20]. The impact of CHF specialists and specialty teams in community health systems is less well understood. Currently there are not enough CHF-trained providers to address this unmet health need. Methods Our institution set out to examine the impact of a CHF disease management program at Holy Cross Hospital, Fort Lauderdale, Florida. Holy Cross Hospital is a 570-bed nontransplant/nonimplant community hospital in metropolitan Fort Lauderdale. Our program infrastructure uses a trained advanced registered nurse practitioner (ARNP) to identify all CHF hospitalized patients and standardize adherence to national guidelines. Additionally, the ARNP facilitates provider follow-up v­ isits after hospital discharge and encourages 1-week follow-up in an ARNP-maintained CHF clinic on our hospital campus. Patients who are referred to the CHF clinic are seen within 1 week to 10 days of discharge by the ARNP team and on a weekly/ as-needed basis until congestion-free stability is achieved. At appropriate intervals, evidence-based treatment is recommended or initiated and titrated according to protocols. Quality-of-life scores are obtained at the index visit and 6-min-walk testing is performed on able patients. The Seattle Heart Failure Risk Assessment is used, when appropriate, to communicate risk with referring providers and drive therapy changes. When mild decompensation episodes occur, patients may receive intravenous diuretics and may be monitored in the clinic. Patients receive additional services such as dietary education or follow-up phone calls (if needed). Family members or support persons are encouraged to accompany patients to the clinic. Patients are seen for up to 1 year, when possible, and discharged from the clinic after 1 year if they maintain continued stability. A CHF fellowship-trained and J. Larned et al., Congestive Heart Failure Clinics b­oard-certified specialist provides program oversight. Patents who exhibit progressive features are referred to the CHF specialist for further management. If appropriate, high-risk patients undergo cardiopulmonary exercise testing and right-sided heart catheterization, and are referred to tertiary systems for potential stage D therapies such as transplant or left ventricular assist device (LVAD) therapy. If appropriate, patients are referred for palliative care by the CHF clinic. As a means of tracking our outcomes, we created a CHF clinic disease management registry where individual data were entered on a recurring-visit basis. We used this r­egistry to conduct our analysis. Our hypothesis was that management in our CHF clinic would result in a primary end point of fewer hospitalizations compared with all patients discharged with CHF at our community-based ­ ­ institution. We also used our registry to review mortality and appropriate use of evidence-based medicines with systolic CHF. A total of 384 patients were seen in the CHF clinic and entered into the CHF registry between 2012 and 2015. A detailed medical record review of patients with a diagnosis of heart failure based on International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) coding during the 3-year timeframe was done. Data regarding age, sex, type of heart failure, New York Heart Association (NYHA) class, ejection fraction, serum creatinine and brain natriuretic peptide values, and readmission and mortality rates within 30 days, 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year were collected. Fifty-nine patients were lost to follow-up and were not included in our analysis. The registry data were analyzed with Pearson’s chi-square test and Fischer’s exact test, and independent samples t tests were used to compare the baseline characteristics. All analyses were performed with SPSS for Windows version 16.0. Results The baseline characteristics of CHF clinic enrollees are given in Table 1. Most of our patients had NHYA class II heart failure symptoms (72%); 28% had NYHA class III-IV heart failure symptoms. Patients were likelier to receive standard medical therapy if they were enrolled in the CHF clinic. Our usage rate of beta-blocker and ­ angiotensin-converting 15 Table 1 Baseline Characteristics of Congestive Heart ­Failure Clinic Enrollees. Number of enrolled patients Age, years Median IQR Female, % Systolic heart failure, % Ejection fraction Median IQR NYHA class III–IV, % Serum creatinine, mg/dL Median IQR NT-BNP, pg/mL Median IQR 384 76 63–85 40 77 35 25–55 28 1.18 0.92–1.69 3365 1546–6847 IQR, interquartile range; NT-BNP, N-terminal brain ­natriuretic peptide, NYHA, New York Heart Association. enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin-receptor blocker therapy in patients with systolic heart failure is illustrated in Table 2. Readmission and mortality rates for patients enrolled in the CHF clinic is shown in Table 3. As shown in Table 4, the effect of evidenceTable 2 Medication Use in Systolic Congestive Heart ­Failure. Medications Use (%) ACEI/ARB Evidence-based beta-blockers Aldosterone antagonist ACEI/ARB at the maximum target Beta-blocker at the maximum target 92 98 30 44 38 ARB, angiotensin-receptor blocker; ACEI, angiotensin-­ converting enzyme inhibitor. Table 3 Readmission and Mortality Rates for Patients ­Enrolled in the Congestive Heart Failure Clinic. Period Readmission (%) Mortality (%) 30 days 3 months 6 months 1 year 7 12 16 19 2 4 9 15 16 J. Larned et al., Congestive Heart Failure Clinics Table 4 Effect of Evidence-Based Medications at Maximum Target Dosages on Readmission and Mortality Rates. Use of medications at maximum dosages Readmission (%) Mortality (%) Yes No P 5 9 0.29 2 2 0.60 based medications at maximum target dosages on readmission and mortality rates was not statistically significant. However, we were able to demonstrate a statistically significant difference in readmission rates between patients who were followed up in the CHF clinic versus those who were not seen in the CHF clinic (Figure 1). Discussion Our CHF clinic has been able to demonstrate a consistent favorable impact on readmission rates versus readmission rates for CHF patients who were not referred to a community-based CHF clinic, as illustrated in Figure 1. Over the 1-year course of longitudinal follow-up in the CHF clinic, the readmission risk increased in all groups, thereby reflecting the risk of CHF progression. Recurrent CHF hospitalizations indicate a higher risk prognosis across multiple CHF clinical trials, which supports why our center tries to maintain longitudinal care for 1 year, when possible [21, 22]. One explanation for our favorable readmission data may lie in our follow-up protocols. Our followup regimen is rigorous, encouraging patients to be followed up in the CHF clinic on a weekly basis, until they are deemed clinically stable, then on a 1–3-month recurring basis for 1 year after hospitalization. Urgent visits are encouraged, and mild to moderate CHF decompensations are treated with intravenous diuretics, as needed, in the clinic. Patients are encouraged to call the CHF clinic if there is a change in their clinical status, and recommendations may be made to patients accordingly via the telephone. Nutritional services and social support services are provided to all patients enrolled in the CHF clinic. If indicated, home health and cardiac rehabilitation is provided to appropriate patients. Monthly educational group sessions are held for enrolled patients though our Heart Failure University to promote CHF self-management. This medical home approach seems to provide an infrastructure that allows more mechanisms to intervene on CHF patients and across the spectrum of their illness. Our follow-up protocol may be a more costeffective alternative in the context of the cost of a CHF admission along with readmission penalties. As described above, our experience demonstrates that most of our CHF clinic patients had NHYA class II symptoms. This may be attributable to careful management and follow-up of our patient population. Even when medical therapy could not be achieved to target doses, patients still had fewer hospital events and fewer CHF symptoms. Despite 18 HF clinic patients 16 Non-clinic patients 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 2012 (P-value 0.002) 2013 (P-value 0.0003) 2014 (P-value 0.012) 2015 (P-value 0.04) Figure 1 Readmission Rates of Congestive Heart Failure (HF) Clinic Patients versus Nonclinic Patients (2012–2015). J. Larned et al., Congestive Heart Failure Clinics their mean ejection fraction and baseline N ­ -terminal brain natriuretic peptide levels, only 28% of our population had severe CHF symptoms as defined by NHYA class III or greater. Across the NYHA classes we report 15% mortality at 1 year for CHF clinic enrollees. This statistic was not significantly related to achieving target therapy, according to our data. Yet, our mortality rates at 1 year were lower than rates reported by other investigators [23–25]. With regard to a comparison group, we do not have complete mortality data on those CHF patients who were discharged from our hospital but were not followed up in the CHF clinic. We were able to achieve a high usage rate of betablocker and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin-receptor blocker therapy in patients with systolic heart failure. Accordingly, we report a lower usage rate of aldosterone antagonist therapy in systolic heart failure patients. Our aldosterone antagonist use may reflect the fact that, although aldosterone antagonists are integrated into the current guidelines for use in systolic heart failure of NYHA class II or greater, they tend to be used less in patients with NYHA class II CHF [26, 27]. This may also reflect the challenges of aldosterone antagonists and their side effects in an elderly population. In our experience, our specialty team consisting of a CHF-trained ARNP and CHF-trained cardiologist may have impacted our CHF clinic outcomes. CHF community hospital programs represent opportunities to identify patients who may be “CHF rapid progressors.” Early identification of the highest-risk CHF patients facilitates early evaluation and referrals for stage D therapies such as LVAD therapy, transplant, inotropes, palliative care, or hospice care. Study Limitations Our sample size is small and likely reflects our referral patterns within our hospital system. Our experience demonstrates the challenges in treating CHF within a nontransplant/nonimplant community hospital setting. Our hospital system is not unique in that it is an “open” system where both hospitalemployed and non–hospital employed physicians may treat CHF patients when they are admitted to the hospital. Hospitalized heart failure patients are 17 likelier to be referred to the CHF clinic if they are admitted to the hospitalist service or a hospital medical group service versus a nonemployed provider. Therefore, the bulk of our analysis is limited to those patients who were ultimately referred to the CHF clinic. Secondly, during our CHF clinic’s early existence, our impact was lessened by the fact that we were confined initially to making recommendations rather than directly changing therapy. We were able to shift from an advisory role to a more active role within the first year, but it stands to reason that this initial limitation may have affected our outcomes. Our data do not account for decompensation episodes within the CHF clinic population. In fact, decompensation episodes did occur in our clinic population but in many circumstances could be managed in an outpatient setting by either administration of intravenous diuretics in the clinic or through increase of oral diuretic therapy followed by rapid follow-up in the clinic. Conclusion and Take-Home Message We conclude that CHF community hospital clinics that use a rapid and frequent follow-up format with an ARNP with CHF specialist oversight effectively reduce rehospitalization rates at 1 year. We demonstrate that CHF-trained teams are likelier to place emphasis on evidence-based therapy and achieve greater symptom relief. Having a CHF-trained team in a community hospital setting may create an extra edge that allows earlier recognition of high-risk CHF and facilitate appropriate referrals for LVAD therapy, transplant, or palliative care. This construct presents potential opportunities to reduce medical costs at it pertains to the CHF epidemic. Future directions in CHF management should focus on improving and standardizing the delivery of heart failure care in a community setting. Conflict of Interest The authors declare no conflict of interest. Funding This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or notfor-profit sectors. 18 J. Larned et al., Congestive Heart Failure Clinics References 1. Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics – 2013 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2013;127:e6–245. 2. Roger VL. Epidemiology of heart failure. Circ Res 2013;113:646–59. 3. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Drazner MH, Fonarow GC, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:1495–539. 4. Hall MJ, DeFrances CJ, Williams SN, Golosinskiy A, Schwartzman A. National Hospital Discharge Survey: 2007. Natl Health Stat Report 2010;26:1–20, 24. 5. Krumholz HM, Merrill AR, Schone EM, Schreiner GC, Chen J, ­Bradley EH, et al. Patterns of hospital performance in acute myocardial infarction and heart failure 30-day mortality and readmission. Circ Cardiovascular Quality Outcomes 2009;2:407–13. 6. Mahmood SS, Wang TJ. The epidemiology of congestive heart failure: the Framingham Heart Study perspective. Glob Heart 2013;8:77–82. 7. Akosah KO, Schaper AM, Havlik P, Barnhart S, Devine S. Improving care for patients with chronic heart failure in the community: the importance of a disease management program. Chest 2002;122:906–12. 8.Fonarow GC, Stevenson LW, ­Walden JA, Livingston NA, Steimle AE, Hamilton MA, et al. Impact of a comprehensive heart failure management program on hospital readmission and functional status of patients with advanced heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997;30:725–32. 9. Ramahi TM, Longo MD, Rohlfs K, Sheynberg N. Effect of heart failure program on cardiovascular drug utilization and dosage in patients with chronic heart failure. Clin Cardiol 2000;23:909–14. 10.Whellan DJ, Gaulden L, ­ Gattis WA, Granger B, Russell SD, ­Blazing MA, et al. The benefit of implementing a heart failure disease management program. Arch Intern Med 2001;161:2223–8. 11. Viswanathan M, Kahwati LC, Golin CE, Blalock SJ, Coker-Schwimmer E, Posey R. Medication therapy management interventions in outpatient settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:76–87. 12. Driscoll A, Worrall-Carter L, Hare DL, Davidson PM, Riegel B, Tonkin A, et al. Evidence-based chronic heart failure management programs: reality or myth? Qual Saf Health Care 2009;18:450–5. 13.Driscoll A, Worrall-Carter L, McLennan S, Dawson A, O‘Reilly J, Stewart S. Heterogeneity of heart failure management programs in Australia. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2006;5:75–82. 14. Akosah KO, Moncher K, Schaper A, Havlik P, Devine S. Chronic heart failure in the community: missed diagnosis and missed opportunities. J Card Fail 2001;7:232–8. 15.Fonarow GC, ADHERE Scientific Advisor Committee. The acute decompensated heart failure national registry (ADHERE): opportunities to improve care of patients hospitalized with acute decompensated heart failure. Rev Cardiovasc Med 2003;7:21–30. 16. Amarasingham R, Moore B, Tabak Y, Drazner MH, Clark CA, Zhang S, et al. An automated model to identify heart failure patients at risk for 30-day readmission or death using electronic medical record data. Med Care 2010;48:981–8. 17. Bindman AB, Grumbach K, Osmond D, Komaromy M, ­Vranizan K, Lurie N, et al. Preventable hospitalizations and access to health care. J Am Med Assoc 1995;274:305–11. 18. Billings J, Anderson GM, Newman LS. Recent findings on preventable hospitalizations. Health Aff (Millwood) 1996;15:239–49. 19.Blustein J, Hanson K, Shea S. Preventable hospitalizations and socioeconomic status. Health Aff (Millwood) 1998;17:177–89. 20. Culler SD, Parchman ML, Przybylski M. Factors related to potentially preventable hospitalizations among the elderly. Med Care 1998;36:804–17. 21. Kommuri NV, Koelling TM, Hummel SL. The impact of prior heart failure hospitalizations on long-term mortality differs by baseline risk of death. Am J Med 2012;125(2):209.e9–e15. 22. Krumholz HM, Lin Z, Keenan PS, Chen J, Ross JS, Drye EE, et al. Relationship between hospital readmission and mortality rates for patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, or pneumonia. J Am Med Assoc 2013;309(6):587–93. 23.Curtis LH, Greiner MA, ­Hammill BG, Kramer JM, Whellan DJ, Schulman KA, et al. Early and long-term outcomes of heart failure in elderly persons, 2001–2005. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:2481–8. 24. Kosiborod M, Lichtman JH, Heidenreich PA, Normand SL, ­ Wang Y, Brass LM, et al. National trends in outcomes among elderly patients with heart failure. Am J Med 2006;119:616.e1–7. 25. The SOLVD Investigators. Effect of enalapril on survival in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions and congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med 1991;325:293–302. 26.The RALES Investigators. Effectiveness of spironolactone added to an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and a loop diuretic for severe chronic congestive heart failure (the Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study [RALES]). Am J Cardiol 1996;78:902–7. 27. Boccanelli A, Mureddu GF, Cacciatore G, Clemenza F, Di ­ Lenarda A, Gavazzi A, et al. Antiremodelling effect of canrenone in patients with mild chronic heart failure (AREA IN-CHF study): final results. Eur J Heart Fail 2009;11(1):68–76.