More On the Laplace Transform

advertisement

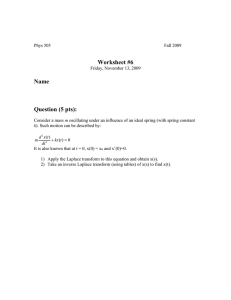

More On the Laplace Transform The Impulse Response We have seen that we can solve the initial value problem yÝ0Þ = y v Ý0Þ = 0 LßyÝtÞà = fÝtÞ, by applying the Laplace transform to get PÝs Þ ŷÝsÞ = !fÝsÞ Then ŷÝsÞ = PÝsÞ = characteristic polynomial for L where 1 !fÝsÞ, PÝsÞ and if we denote by YÝtÞ the inverse transform of 1 , then PÝsÞ t yÝtÞ = Y D fÝtÞ = X YÝt ? bÞ fÝbÞ db. 0 Note that 0 yÝ0Þ = X YÝ0 ? bÞ fÝbÞ db = 0, 0 and t y v Ý0Þ = YÝ0ÞfÝtÞ + X Y v Ýt ? bÞ fÝbÞ db| t=0 = 0, 0 so this solution does satisfy the homogeneous initial conditions. Now suppose that the forcing function f(t) is such that its Laplace transform is just 1. In this case !fÝsÞ = 1 implies ŷÝsÞ = 1 PÝsÞ and yÝtÞ = YÝtÞ. Evidently, Y(t) is the solution of the initial value problem in the special case that the forcing has 1 for its Laplace transform. Then the question is, ”what is this f(t)?” One approach to this question is to recall that LßHÝtÞà = 1s where HÝtÞ = 0 if t ² 0 1 if t > 0 Then by property 3 of the Laplace transform, LßH v ÝtÞà = 1 ? HÝ0Þ = 1, which implies that the f(t) we are seeking is the derivative of HÝtÞ. It is usual to denote this 1 ”function” by NÝtÞ but whatever notation is used, the fact remains that HÝtÞ has no derivative in the setting of classical analysis. There is a well developed theory of generalized functions in which the step function can be differentiated but we will not try to pursue this here. Instead we will simply note that if HvÝtÞ did exist then the integration by parts formula would imply that for any b > 0 and any smooth function dÝtÞ which tends to zero as t ¸ K, K K v X 0 H v Ýt ? bÞ dÝtÞ dt = H Ýt ? bÞ dÝtÞ| t=K t=0 ? X 0 H Ýt ? bÞ d ÝtÞ dt But HÝtÞ = 0, for t ² 0, and dÝtÞ = 0 at t = K, hence H Ýt ? bÞ dÝtÞ| t=K t=0 = 1 6 dÝKÞ ? HÝ?bÞdÝ0Þ = 0 K K X 0 H Ýt ? bÞ d v ÝtÞ dt = X b d v ÝtÞ dt = dÝKÞ ? dÝbÞ, In addition K X 0 H v Ýt ? bÞ dÝtÞ dt = dÝbÞ. and therefore Then we take the defining property of NÝt ? bÞ = H v Ýt ? bÞ to be K X 0 NÝt ? bÞ dÝtÞ dt = dÝbÞ for any smooth function dÝtÞ which tends to zero as t ¸ K. This suggests (but only suggests, it is not true in the setting of classical analysis) that NÝt ? bÞ is very large near t = b and is very small when t is not close to b. Physically we think of NÝt ? bÞ as an idealization of something called an ”impulse”, an input of very high intensity concentrated on a very small time interval. We repeat that this notion is only figurative and can not be rigorously justified. Now, using the definition given above for NÝt ? bÞ, we have K LßNÝt ? bÞà = X NÝt ? bÞ e ?st dt = e ?sb 0 and K LßNÝtÞà = X NÝtÞ e ?st dt = e ?sb | b=0 = 1. 0 Then YÝtÞ is the response to an impulse input of the system described by the initial value problem. Y(t) is often called the ”impulse response”. Evidently, Y(t) can be defined by either of two equivalent specifications, namely ÝaÞ LßyÝtÞà = 0 and yÝ0Þ = 0, y v Ý0Þ = 1 ÝbÞ LßyÝtÞà = NÝtÞ and yÝ0Þ = 0 = y v Ý0Þ Once Y(t) is known, the initial value problem is completely solved. To see this, consider 2 LßyÝtÞà = y”ÝtÞ + by v ÝtÞ + cyÝtÞ = 0, yÝ0Þ = A, y v Ý0Þ = B PÝsÞ ŷÝsÞ ? sA ? B ? bA = 0, Then and ŷÝsÞ = ÝB + bAÞ 1 +A s . PÝsÞ PÝsÞ yÝtÞ = ÝB + bAÞ YÝtÞ + A Y v ÝtÞ It follows that where we used property 3 again to show L ?1 s PÝsÞ = Y v ÝtÞ ? YÝ0Þ = Y v ÝtÞ. Note that yÝ0Þ = ÝB + bAÞ YÝ0Þ + A Y v Ý0Þ = A and y v Ý0Þ = ÝB + bAÞ Y v Ý0Þ + A Y ”Ý0Þ = ÝB + bAÞ + AÝ?bY v Ý0Þ ? cYÝ0ÞÞ = B + bA ? Ab = B. For example, y”ÝtÞ + I 2 yÝtÞ = 0, leads to y v Ý0Þ = B PÝsÞ = s 2 + I 2 , and YÝtÞ = L ?1 so yÝ0Þ = A, 1 PÝsÞ = 1 L ?1 2 I 2 I s +I = 1 sin It I yÝtÞ = B YÝtÞ + A Y v ÝtÞ = B sin It + A cos It. I Additionally, the solution of LßyÝtÞà = y”ÝtÞ + by v ÝtÞ + cyÝtÞ = fÝtÞ, yÝ0Þ = A, y v Ý0Þ = B can be expressed entirely in terms of the impulse response by writing t yÝtÞ = ÝB + bAÞ YÝtÞ + A Y v ÝtÞ + X YÝt ? bÞ fÝbÞ db. 0 Periodic Forcing Functions Suppose fÝtÞ is a periodic function of period T; i.e., fÝtÞ = fÝt ? TÞ for all t > T. 3 Here are two examples. The first, the square wave is piecewise continuous, and is given by SqÝtÞ = 1 if 2k < t < 2k + 1 k = 0, 1, ... ?1 if 2k + 1 < t < 2k + 2 Periodic Square wave The second function, the sawtooth wave is continuous but only piecewise differentiable and is given by WÝtÞ = 1?t if 0<t<2 t?3 if 2<t<4 _ 2k ? 1 ? t k = 1, 2, ... _ if 2k ? 2 < t < 2k t ? Ý2k + 1Þ if 2k < t < 2k + 2 Periodic Sawtooth Wave Now, for f(t) periodic of period T, define f F ÝtÞ = fÝtÞ ? fÝt ? TÞ HÝt ? TÞ = fÝtÞ if 0 < t < T 0 if t > T 4 That is, f F ÝtÞ is ju;st one fundamental period of fÝtÞ. Then by the result for the transform of a shift, we have !f F ÝsÞ = !fÝsÞ ? !fÝsÞ e ?Ts = !fÝsÞÝ1 ? e ?Ts Þ !fÝsÞ = and hence !f F ÝsÞ Ý1 ? e ?Ts Þ where !f F ÝsÞ = X T fÝtÞ e ?st dt. 0 For example, 2 LßSq F ÝtÞà= ŜqÝsÞ = X S qF ÝtÞ e ?st dt 0 1 2 = X e ?st dt ? X e ?st dt = 1s ße ?2s ? 2e ?s + 1à. 0 1 This is the transform of the fundamental period of the square wave. Now we recall a result from high school algebra, namely for |r| < 1, the sum of a geometric series is given by, K 1 + r + r2 + ` = > rn = n=0 1 . 1?r K 1 = > e ?Tsn = 1 + e ?Ts + e ?2Ts + ` Ý1 ? e ?Ts Þ n=0 Then Now consider the problem LßyÝtÞà = fÝtÞ, yÝ0Þ = y v Ý0Þ = 0 where fÝtÞ is periodic of period T. Then ŷÝsÞ = 1 !f ÝsÞ ß1 + e ?Ts + e ?2Ts + `à, PÝsÞ F so, if we let y F ÝtÞ = L ?1 implies, 1 !f F ÝsÞ , then the shifting property of the Laplace transform PÝsÞ yÝtÞ = y F ÝtÞ + y F Ýt ? TÞ HÝt ? TÞ + y F Ýt ? 2TÞ HÝt ? 2TÞ + ` Example: y vv ÝtÞ + 16 yÝtÞ = WÝtÞ, yÝ0Þ = 0, y v Ý0Þ = 0, 5 where WÝtÞ denotes the period 4 sawtooth wave defined earlier. Then, letting T 2 4 Ŵ F ÝsÞ = X WÝtÞ e ?st dt = X Ý1 ? tÞ e ?st dt + X Ýt ? 3Þ e ?st dt 0 0 2 = 2e ?2s s + e ?2s + s ? 1 ? e ?2s e ?2s s + e ?2s + s ? 1 s2 s2 = 2 1s ? 12 s we have and + e ?2s 1s + 32 s ? e ?4s 1s + 12 s . Ýs 2 + 16ÞŷÝsÞ = Ŵ F ÝsÞß1 + e ?4s + e ?8s + `à Ŵ F ÝsÞ ß1 + e ?4s + e ?8s + `à. s 2 + 16 ŷÝsÞ = Then yÝtÞ = y F ÝtÞ + y F Ýt ? 4ÞHÝt ? 4Þ + y F Ýt ? 8ÞHÝt ? 8Þ + ` where y F ÝtÞ = L ?1 = 1 8 Ŵ F ÝsÞ s 2 + 16 1 ? t ? cosÝ4tÞ + 14 sinÝ4tÞ 1 + 16 HÝt ? 2Þ 1 + 3Ýt ? 2Þ ? cos 4Ýt ? 2Þ ? 34 sin 4Ýt ? 2Þ 1 ? 16 HÝt ? 4Þ 1 ? Ýt ? 4Þ ? cos 4Ýt ? 4Þ + 14 sin 4Ýt ? 4Þ 6