Television`s Performance on Election Night 2000 A

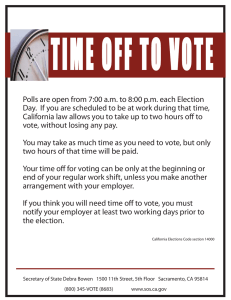

advertisement