Developmental Review 22 (2002) 623–643

www.academicpress.com

Does child temperament moderate

the influence of parenting on adjustment?q

Kathleen Cranley Gallagher

Department of Educational Psychology, University of Wisconsin–Madison,

Education Sciences Building, 1025 West Johnson Street, Madison, WI 53706, USA

Received 26 March 2001; received in revised form 3 January 2002

Abstract

Parental socialization and child temperament are modestly associated with child

adjustment outcomes. Main-effects models have yielded valuable information, but fail

to explicate mechanisms via which child adjustment occurs. A conditional model of

influence is suggested, in which parenting effects on child adjustment are moderated

by child temperament characteristics. Theoretical support for such a model is outlined, integrating bioecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998)

and a corollary differential susceptibility hypothesis (Belsky, 1997). Empirical work

compatible with the moderated model is reviewed, and research that more fully integrates the theoretical model and allows direct testing of the propositions is presented.

Ó 2002 Elsevier Science (USA). All rights reserved.

Keywords: Parenting; Temperament; Child adjustment; Moderator; Ecological systems theory;

Differential susceptibility

Research linking parenting and child temperament to adjustment has relied primarily upon main-effects models, in which socialization (parenting) or

biological predisposition (temperament) directly predicts child adjustment

q

An earlier version of this paper was presented as part of preliminary examination

requirements for completion of studies in the Ph.D. program in Human Development. I am

most grateful to Deborah Lowe Vandell, Leonard Abbeduto, and B. Bradford Brown for their

generous comments and assistance.

E-mail address: kcgallag@wisc.edu

0273-2297/02/$ - see front matter Ó 2002 Elsevier Science (USA). All rights reserved.

PII: S 0 2 7 3 - 2 2 9 7 ( 0 2 ) 0 0 5 0 3 - 8

624

K.C. Gallagher / Developmental Review 22 (2002) 623–643

outcomes. It has been suggested that research emphasizing the interaction

effects of parenting and child temperament might more precisely consider

the complexity of development and its processes (Hinde, 1989; Kochanska,

1997; Lerner, 1998; Magnusson & Stattin, 1998; Thomas, 1984). A conditional model, in which the relationship between a predictor and dependent

variable is moderated by the presence of a third variable, may be used to examine parenting influences on child adjustment as moderated by child temperament.

In this review, I summarize the work linking parenting and temperament

to adjustment in main-effects models. A theoretical framework and ancillary

hypothesis are then examined. Bioecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998) proposes how specific qualities of parenting have their

most conspicuous effects on adjustment in the presence of distinct child temperament characteristics over time. A differential susceptibility hypothesis

(Belsky, 1997) is proposed as a means for interpreting temperamental instability. A survey of the empirical literature investigating the interaction of

parenting and child temperament will follow. I conclude by suggesting

strategies for future study of parenting–temperament interaction, informed

by bioecological systems theory.

Main-effects models

Adjustment in childhood

Adjustment in childhood refers to the characteristics of the childÕs social

functioning within constraints of the environment (Rothbart & Bates, 1998).

Positive adjustment is reflected in general positive emotion, compliant and

self-regulated behavior, and harmonious interpersonal interactions (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998). Negative adjustment outcomes are reflected

in the converse: negative emotion, disruptive behavior and conflicted social

relationships. What manifests as adjustment in childhood varies with developmental period and with the environmental and social demands placed

upon the child (Sanson & Rothbart, 1995).

Parenting and child adjustment

Parenting is thought to influence adjustment via processes commonly

known as socialization, ‘‘. . .whereby children acquire the habits, values,

goals, and knowledge that will enable them to function satisfactorily when

they become adult members of society’’ (Maccoby, 1980b, p. v). The research linking parenting and child adjustment has generated the study of

two primary dimensions of parenting. Parental warmth incorporates behaviors that convey acceptance, positive affect, sensitivity and responsiveness

K.C. Gallagher / Developmental Review 22 (2002) 623–643

625

toward the child. Parental control consists of sufficient and developmentally

appropriate involvement, discipline and monitoring (Baumrind, 1979; Maccoby, 1980b), manifest in enforcing demands and rules, high expectations,

and restriction of the childÕs behavior. Negative aspects of parental control

have also been considered, including the effects of intrusiveness and harsh

discipline (Patterson, Reid, & Dishion, 1984).

While operational definitions of parental warmth and control vary across

studies, general findings associating parenting with child adjustment can be

summarized as follows. High maternal warmth and nonintrusive responding

are related to secure attachment in infancy (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, &

Wall, 1978). In early childhood, parental high warmth and responsiveness

have been associated with superior child prosocial skills (Sroufe, 1985), fewer behavior problems, and better peer relations (Baumrind, 1979). In later

childhood and adolescence, these same parenting characteristics predict fewer behavior problems and more harmonious peer relationships (Baumrind,

1991).

Profoundly negative parenting, manifested in child abuse and neglect, is

also related to maladjustment in childhood and adulthood (Egeland &

Sroufe, 1981). Maltreatment aside, however, predictions of child adjustment

outcomes from parenting behaviors have been modest (Chamberlain & Patterson, 1995; Collins, Maccoby, Steinberg, Hetherington, & Bornstein, 2000;

Maccoby, 1980a; Vandell, 2000; Wachs, 1991). Additionally, links between

parenting styles and child adjustment outcomes have sometimes been equivocal. For example, high parental power, arbitrarily administered, was associated with divergent child outcomes: obedient, passive behavior in some

children and aggressive cruel behavior in others (Maccoby, 1980a). Modest

relations and equivocal findings have led to reflection on what alternative

influences might be playing a role in the childÕs developing social competence (Rothbart & Bates, 1998; Sanson & Rothbart, 1995).

Child temperament and adjustment

Child temperament, defined as ‘‘constitutionally based individual differences in emotional, motor, and attentional reactivity and self-regulation’’

(Rothbart & Bates, 1998), is modestly related to concurrent and later child

adjustment. In a direct linkage model, temperamental extremes may reflect

either positive adjustment on one end of the continuum, or pathology on the

other (Rothbart & Bates, 1998). For example, extreme fearfulness may manifest as anxiety disorder, while very low attention may manifest as attention

deficit disorder.

In early studies of child temperament, Chess and Thomas (1989) defined

clusters of temperament characteristics they hypothesized were most clinically salient for adjustment. Children with an ‘‘easy’’ temperament typically

exhibited moderate to high positive emotion, moderate activity level, high

626

K.C. Gallagher / Developmental Review 22 (2002) 623–643

adaptability and high emotional regulation. Children with ‘‘difficult’’ temperament typically exhibited high negative emotion, low adaptability, high

activity level, and low emotional regulation. Children with the difficult characteristics were found to challenge parents, caregivers, and teachers, more

than children with ‘‘easy’’ or average temperament (Thomas, 1984).

Contemporary research in the area of temperament postulates a model

that considers three global dimensions: surgency, negative emotion, and regulation (Rothbart & Bates, 1998). Surgency involves activity level and the

tendency to approach or withdraw from novel situations. Regulation includes systems of attention and behavioral inhibition, and negative emotion

refers to sadness, distress to limitation and soothability. While similar to the

original dimensions of Thomas and Chess, the contemporary structure is

supported by biological, behavioral genetic and social science research

(Rothbart & Bates, 1998).

Regardless of the model employed, characteristics associated with ‘‘difficult’’ temperament are modestly related to later behavior problems (Bates,

1989; Chess & Thomas, 1989; Martin, 1989). High negative emotion in infancy is associated with later internalizing and externalizing behaviors. Inhibition, or fearful withdrawal, is associated with later social inhibition or

shyness (Kagan, 1994), and internalizing problems (Bates, Maslin, & Frankel, 1985). Irritability and distress to limitations is associated with later aggressive behavior (Bates et al., 1985). However, modest relations among

variables, inconsistent findings, and limited theoretical support have rendered main-effects-models of parenting or temperament influence obsolete.

Evidence that parenting influences children (Belsky, Fish, & Isabella,

1991) and that children affect parents (Bell, 1968), persuades us to consider

an alternative model that reflects this underlying bidirectionality and reciprocity. A conditional model, focusing on interactive effects of parenting

and temperament, is one such model.

A conditional model

There has been little theoretical delineation of the synergistic processes of

parenting and temperament, though interactions are often assumed to reflect the bi-directional and reciprocal interchanges between the organism

and environment over time (Hershberger, 1994; Magnusson & Stattin,

1998; Thomas, 1984; Wachs & Plomin, 1991). Thomas and Chess hypothesized that temperament conveyed its influence in interaction with the demands of the environment, including parenting. Positive adjustment was

seen as a product of ‘‘goodness-of-fit’’ between the childÕs temperament

and the environment: ‘‘Simply defined, goodness of fit results when the

childÕs capacities, motivations and temperament are adequate to master

the demands, expectations and opportunities of the environment’’ (Chess

K.C. Gallagher / Developmental Review 22 (2002) 623–643

627

& Thomas, 1989, p. 380). Unfortunately, theoretical and methodological

limitations (see Plomin & Daniels, 1984) have forced goodness-of-fit approaches to remain under-utilized.

The hypothesis of organismic specificity (Wachs, 1991) suggests that individuals may respond differently to the environment according to qualities

of their own reactivity. In other words, the environment influences different

people differently. Wachs outlined the need for a theoretically based study of

organism–environment interactions, including systems, longitudinal, and interaction components, in which the interaction component examines either

differential vulnerability, utilization of environmental opportunities, or differences in response patterns to the environment.

However, joint effects of parenting and temperament are not simply instances of organism–environment interaction. While temperament can be

considered a characteristic of the person, or organism, parenting is more

than a feature of the environment. Parenting is bi-directional and reciprocal

by design; the child is an active participant in the parenting process. Children elicit parenting behavior, and respond in ways that shape parenting

(Bell, 1968). Therefore, the interaction of parenting and child temperament

is a synergism of process (parenting) and person (temperament), as outlined

by bioecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998).

A conditional model aims to uncover and meaningfully interpret interactions, or the nonlinear association between two variables. In the proposed

conditional model, interaction tests the prediction of child adjustment from

parenting characteristics, moderated by child temperament characteristics.

Baron and KennyÕs (1986) influential work on moderator and mediator variables sets forth considerations for exploring the role of third or intervening

variables. Where child temperament moderates the effects of parenting, a

childÕs temperament characteristics increase or decrease the strength of the relationship between parenting (the independent variable) and child adjustment (the dependent variable). Specifically, qualities of parenting may

predict different outcomes for children with different temperament characteristics (Sanson & Rothbart, 1995). Bronfenbrenner and Morris (1998) elaborate on how conditional effects might be explored, posing hypotheses for

child outcomes of dysfunction and competence.

The bioecological systems model

Expanding on the ecological systems model (Bronfenbrenner, 1979;

Bronfenbrenner & Crouter, 1983), Bronfenbrenner and Morris (1998) advance a bioecological model, a theoretical basis for understanding how particular processes, in combination with child characteristics, might

differentially influence development. This model is referred to as the Process–Person–Context–Time model (PPCT), and sets forth implications for

how research might consider the interaction of parenting and temperament.

628

K.C. Gallagher / Developmental Review 22 (2002) 623–643

Parenting proximal processes

The core of the bioecological model is proximal processes (Bronfenbrenner

& Morris, 1998), activities in which the child interacts with persons, objects

or symbols on a regular basis, such as participating in mealtime, listening to

storybooks, and visiting relatives. The influence of proximal processes on developmental outcomes is expected to vary with characteristics of the Person

(child or other), characteristics of the Context (the broader environment),

and elements of Time (duration and historical setting). The quality of proximal processes is theorized to influence child development outcomes more

than any single measure of Person, Context, or Time alone, ‘‘Proximal processes are posited as the primary engines of development’’ (Bronfenbrenner

& Morris, 1998, p. 996). Competent and increasingly complex participation in these proximal processes is necessary for optimal developmental

outcomes.

Parenting is a proximal process in which parental influence on child adjustment varies as a function of the childÕs characteristics, such as temperament. Responsive parenting may reduce the likelihood of social withdrawal

in school in the case of an inhibited child, but not in the case of an uninhibited child. Harsh parenting may be associated with increased child aggression in general, but with even more aggression in the case of children who

express more negative emotion. An example of parenting as a proximal process is found in the socialization of a young childÕs mealtime behaviors. The

parentÕs efforts involve encouraging manners, having the child be healthily

nourished, and somehow avoiding catastrophic messes. The childÕs activity

level, fearfulness regarding novelty (new food), and emotions regarding restrictions (e.g., high chair, bib) influence the parentÕs efforts. The process is

the parent-led reciprocal interchange of the meal activity, constantly influenced by the Person characteristics of the child.

Temperament person characteristics

Person characteristics that moderate the influence of proximal processes

include force and demand characteristics. Force characteristics are the childÕs

‘‘active behavioral dispositions’’ (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998, p. 1009).

Force characteristics such as impulsiveness, angriness, and shyness can encourage or impede development in the context of proximal processes. Demand characteristics evoke or hinder social reactions and behaviors from

others involved in proximal processes. According to Bronfenbrenner and

Morris (1998), temperament can act as force or demand characteristics.

The degree to which a temperament characteristic impedes or facilitates

productive engagement in proximal processes indicates its positive or negative value for the childÕs development. Fearfulness, a force characteristic,

may hinder a childÕs participation with the parent in playgroup activities, reducing the quality and time spent in parent–child proximal processes. Infants high in irritability or activity level, demand characteristics, may

K.C. Gallagher / Developmental Review 22 (2002) 623–643

629

evoke more negative emotional expression from parents in the case of the

former, or more parental restriction in the latter case. The child contributes

to the process through these Person characteristics, moderating the association of parenting and child outcomes.

A conditional model of influence

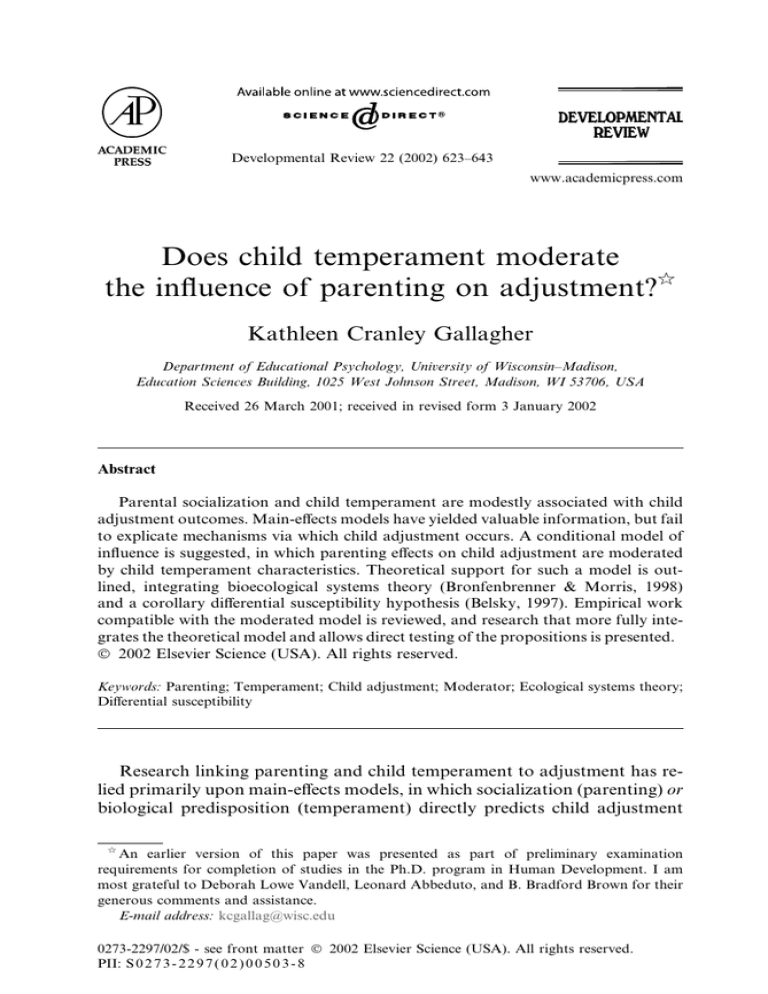

Bronfenbrenner and Morris theorize that Proximal Processes and Person characteristics synergistically predict developmental outcomes. Proximal Processes become more elaborate over time. Parenting and child

temperament interact such that the total effect is greater than the addition

of their separate contributions (see Fig. 1). Distressful emotion, inhibitory

fearfulness, and high activity level render a child less able to engage in increasingly complex proximal processes, and make negative adjustment

outcomes more likely. Questions this model can begin to address are plentiful. Are there situations in which typically negative processes or negative

temperament are associated with positive outcomes? Might it be adaptive

for parents to be less sensitive to childrenÕs need for autonomy in dangerous contexts, such as urban settings or political conflict? Do certain temperament characteristics interact with aspects of parenting more than

others?

The bioecological theory of development is consistent with Wachs and

PlominÕs (1991) requirements for a theoretical model of organism–environment interaction. The systems components, outlined in detail in earlier

works by Bronfenbrenner (i.e., microsystems, mesosystems), help to account

for the complexity of the environmental influences in a childÕs life (see Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Bronfenbrenner & Crouter, 1983). A longitudinal component, inherent in BronfenbrennerÕs concept of Time, considers

developmental progress within and over periods of time. An interactive

Fig. 1. Expected child adjustment outcomes as predicted by the interaction of child temperament

and parenting.

630

K.C. Gallagher / Developmental Review 22 (2002) 623–643

component is also included. Over 20 years ago, Bronfenbrenner (1979) stated, ‘‘. . .the principal main effects are likely to be interactions’’ (p. 38).

An ancillary hypothesis

An additional perspective for examining the associations among parenting, child temperament and child adjustment is a hypothesis of differential

susceptibility (Belsky, 1997, 2001), which incorporates evolutionary considerations into study of the Process–Person–Context framework of ecological

systems theory. According to the evolutionary perspective, variation among

individualsÕ behavioral characteristics occurs to enhance individual reproductive fitness. Variation in individual characteristics increases the likelihood that the most adaptive characteristics advance into the next

generation, with consistently maladaptive characteristics extinguishing over

time. Since the future remains uncertain, and with it the human characteristics that may adapt best to future contexts, it makes sense, contends Belsky, that the offspring of individuals vary in the degree to which they

exhibit certain characteristics. This is particularly valuable within families,

in which parentsÕ best interest for promoting their genes into this uncertain

future is having offspring who vary in their characteristics, or as Belsky

(2001) depicts it, a reproductive ‘‘hedging of bets’’ (p. 7).

Belsky (1997) suggests that what plausibly follows is variation among individuals in the characteristic of ‘‘susceptibility to environmental influence’’

(p. 184). Just as there is variation among characteristics such as athletic ability, or body type, individualsÕ traits may vary in their susceptibility to socialization influences, including parenting. Thus, some offspring are expected to

be affected by socialization experiences—in positive and/or negative ways,

depending on the nature of their experiences—whereas others are expected

to be affected to a far less degree, if at all.

The differential susceptibility hypothesis complements bioecological theory in its consideration of conditional effects (Belsky, 1997). Mounting evidence suggests that infants high in negative reactivity may be more

susceptible to variations in parenting than their non-reactive peers (see

Fig. 2), particularly in relation to outcomes of behavioral adjustment and

regulation.

As an example of how this might manifest, highly reactive, or negative,

infants might be more susceptible to parentsÕ socialization pressures than

their less reactive peers. ParentsÕ efforts to encourage or discourage this reactivity may be associated with child outcomes of social inhibition or social

facility, respectively. Conversely, children who are less reactive and negative

may be more prone to resist parental socialization, and may develop social

competence with or without parental facilitation. Whether this susceptibility

to influences is specific to characteristics or global, within the organism, remains uninvestigated.

K.C. Gallagher / Developmental Review 22 (2002) 623–643

631

Fig. 2. Expected differential susceptibility of negative temperament to the influence of parenting

on child adjustment outcomes.

Empirical work employing a conditional model

There is a small body of literature exploring the interactive effects of parenting and child temperament as related to adjustment, possibly due to difficulty in obtaining and interpreting significant interaction terms (Sanson &

Rothbart, 1995). The literature reviewed spans the developmental periods of

childhood, with child adjustment manifested differently at each developmental stage: attachment security in infancy, prosocial and antisocial skills in

early childhood, and aggression and depression in middle and late childhood.

Adjustment in infancy: Attachment security

Findings linking attachment to later positive adjustment indicate that a

secure attachment relationship between caregiver and child is a hallmark

of positive adjustment in infancy (Rutter, 1997; Suess, Grossman, & Sroufe,

1992). In a short-term longitudinal study of 48 infants and their mothers,

Crockenberg (1981) found that newborn irritability interacted with motherÕs

social support, predicting attachment security in the Strange Situation at one

year. Mothers who reported low levels of social support were more likely to

have infants who were insecurely attached, but only when those infants were

irritable as newborns. CrockenbergÕs instrumental study paved the way for

how we might think about the complexity of parenting characteristics, child

632

K.C. Gallagher / Developmental Review 22 (2002) 623–643

temperament and adjustment in infancy. Particularly remarkable is the influential nature of negative temperament on the association between parenting

processes and child adjustment.

Mangelsdorf, Gunnar, Kestenbaum, Lang, and Andreas (1990) explored

similar issues in a multi-measure study of temperament, parenting and attachment security. The researchers observed 66 nine-month old infants

and their mothers at home, assessing infant temperament and maternal personality. Attachment security in the Strange Situation was assessed when

the infants were thirteen months old. Neither child temperament nor maternal behavior predicted later emotional expressiveness or attachment security. However, maternal constraint, a personality type reflecting ‘‘rigidity,

traditionalism and low risk-taking’’ (p. 824) interacted with temperament

to predict attachment. Low maternal constraint predicted secure attachment for infants prone to distress; whereas maternal constraint, whether

high or low, was unrelated to attachment security for infants not prone

to distress.

In both of these studies, features of parenting interacted with temperament, predicting child adjustment outcomes; however, parenting proximal

processes did not interact with temperament. Robust measurement of parenting in infancy may be difficult, as the proximal processes of mother–infant interaction may be insufficiently established (Kochanska, 1998). Irritable

infants were more susceptible to parenting influences than non-irritable

infants, however, supporting the differential susceptibility hypothesis.

Adjustment in early childhood: Prosocial and antisocial behavior

Research with preschoolers has more wholly documented parenting–

temperament interaction. For children 2–5 years old, opportunities for

social interaction outside of the home increase in the contexts of playgroup, neighborhood, and preschool. Prosocial behavior is reflected in

positive behaviors that advance relationships, such as helpfulness, sharing, and empathy. Social inhibition reflects the converse: failure to engage

relationships with others, and in the extreme, social withdrawal (Rutter,

1997).

Prosocial behavior

KochanskaÕs model (1995, 1997) tests the joint influences of parental socialization and child temperamental inhibition in relation to childrenÕs moral development. Kochanska (1997) explored how parental socialization

behaviors, such as responsiveness and discipline, interacted with child fearfulness to predict childrenÕs conscience-related behaviors. With a sample of

90 toddlers and their mothers, child fearfulness was measured using parent

report and a laboratory observation, including a ‘‘risky events’’ activity.

Maternal responsiveness (sensitivity, acceptance, and cooperation) and

K.C. Gallagher / Developmental Review 22 (2002) 623–643

633

gentle discipline (reasoning and low-power guidance) were observed in a

separate series of mother–child laboratory activities: a cooperative play

‘‘kitchen scene,’’ a toy clean-up and a prohibited toy situation. Child conscience was measured at 4- and 5-years old in the laboratory, where the child

was challenged to not cheat in two rigged games, and enact moral dilemmas

with dolls and props.

Maternal gentle discipline predicted higher conscience scores only for

children high in fearfulness. Maternal responsiveness was also related to

higher conscience scores, but only for children rated low in fearfulness. Kochanska asserted that the pathways to internalization are different for children who differ on fearfulness, and that strong parental power interferes

with the internalization of social morals. Thus, for fearful children, capitalization on their fearfulness, in the use of gentle, psychological discipline was

sufficient for positive moral development. For fearless children, characteristics of the mother–child relationship itself, such as maternal responsiveness,

provided support needed for children to internalize morals.

Stanhope (1999) also investigated interaction of child temperament and

parent discipline in relation to prosocial behavior. With a sample of 56 preschoolers and their parents (49 mothers and 8 fathers), Stanhope measured

parent report of child negative emotionality and parent-reported discipline.

Child sharing behavior was observed for 20 min during free play in the nursery school setting. Low-power parental discipline was related to higher sharing in the nursery school, but only for children high in negative

emotionality. Like Kochanska, Stanhope posited that low power parenting

helped fearful children to develop prosocial behavior with peers.

These two studies provide evidence that ‘‘gentle’’ or ‘‘low power’’ discipline is associated with both internalized (conscience) and externalized

(sharing) prosocial behavior, for children who demonstrate high negative

emotion or fearfulness. Parenting processes exerted influence on childrenÕs

development in interaction with temperament characteristics of the Person

(child). Additionally, temperament characteristics were differentially susceptible to parental influences, in that highly inhibited children were more likely

to be affected by variation in parental discipline.

Social inhibition

Preschool children face increasing demands of social interaction. Social

inhibition, or shyness, may put a child at risk for social withdrawal and poor

peer relations (Rubin, Stewart, & Chen, 1995). Park, Belsky, Putnam, and

Crnic (1997) observed the emotional expression of 125 firstborn males when

the children were 10 months old. Infant positive temperament (laughter/

smiling and orientation) and negative temperament (fear and distress-tolimitations) were derived from a parent report and laboratory observation.

Parenting processes were observed in the home, when the children were 15,

21, 27, and 33 months old; mothers and fathers were rated on positive affect,

634

K.C. Gallagher / Developmental Review 22 (2002) 623–643

negative affect, sensitivity, and intrusiveness. When the children were 3-years

old, they participated in a series of activities in the laboratory, which were

coded for social ‘‘wariness’’: facial expression of fear or shyness, bodily tension, hesitation to respond or interact, and proximity-seeking with parent.

Interaction of parenting processes and child temperament predicted child

wariness in the lab. When mothers were intrusive, asserting their own objectives over those of the child, only highly negative infants were more wary at

3 years. Similarly, when fathers were highly intrusive, negative, less sensitive

and less affectionate, negative infants were less wary at 3-years. These findings contradicted the authorsÕ expectation that intrusive, affectively negative

parenting would lead to negative adjustment outcomes. However, Kagan

(1997) has suggested that parentsÕ intrusiveness might be necessary for fearful children, in order to encourage interaction with people.

Early, Rimm-Kaufman, Cox, and Saluja (1999) reported contradictory

findings in their examination of interaction between maternal sensitivity

and child wariness in relation to social adjustment in the first week of kindergarten. Child behavioral inhibition was evaluated at 15 months in the

Strange Situation with 235 children and their mothers. Maternal sensitivity

was observed in three structured mother–child activities. When the children

completed their first week of kindergarten, teachers reported child levels of

active engagement and withdrawal in the classroom. Maternal sensitivity interacted with wariness in prediction of kindergarten adjustment. Sensitive

mothering was related to more active engagement with other children and

less inactive (passive) withdrawal in kindergarten, but only for children

who were highly fearful at 15 months. According to the investigators, mothering that was affectively warm and responsive to the infant provided a base

of emotional support for the fearful child, which could be generalized to

prosocial behavior with peers.

The findings in the two social inhibition studies differ dramatically. In one

case (Park et al., 1997) less sensitive, negative parenting processes predicted

less social inhibition for children who were more negative in infancy, while

in the other (Early et al. (1999)) positive parenting processes predicted less

social inhibition for children who were negative as infants. While the studies

varied on several dimensions (i.e., age and gender of child), an explanation

drawn from Bronfenbrenner and Morris (1998) suggests that proximal processes function differently in relation to distinct outcomes. Differences in the

parenting predictors of social inhibition between the two samples may have

been due to differences in the outcome contexts.

When parenting was less solicitous, fearful infants may have clung less to

parents and demonstrated less fearfulness in social situations with parents

present. When parented sensitively, children who were fearful as infants

may have later been less inhibited in the presence of novel peers and situations. Alternatively, child adjustment outcomes may reflect some aspect of

the attachment working model. When parents were intrusive with fearful

K.C. Gallagher / Developmental Review 22 (2002) 623–643

635

infants, lack of inhibition in the lab with parents present may have indicated

an avoidant attachment relationship. For inhibited children who were parented sensitively, less inhibition in a novel environment may have indicated

a secure attachment relationship (Suess et al., 1992). Clearly, more research,

including replication, is needed to sort through these discrepancies.

Adjustment in the school years: Externalizing and internalizing pathology

In middle childhood and adolescence the child spends substantial

amounts of time in non-family environments, increasing expectations on

the childÕs ability to interact socially. Maladjustment in this developmental

period is made manifest by externalizing (e.g., aggression) and internalizing

behaviors (e.g., withdrawal and depression) (Sanson & Rothbart, 1995). Parental socialization research often focuses on discipline, measured by parent

involvement, monitoring consistency, and rigidity (Chamberlain & Patterson, 1995).

Blackson, Tarter, and Mezzich (1996) explored the concurrent interaction

of parental discipline and temperament in a sample of 152 pre-adolescent

boys. The 10–12-year old boys reported their own temperament and their

parentsÕ discipline. Child difficult temperament was characterized by high activity, high fearful withdrawal, high negative emotion and low adaptability.

Parental discipline incorporated consistency and severity, with high ratings

of both indicating negative discipline. Mothers reported child internalizing

and externalizing behaviors.

Parental discipline and child temperament interacted, predicting both

internalizing and externalizing behaviors. When parents used negative discipline, externalizing behavior was more prevalent in children with difficult temperament than in non-difficult children. The interaction of

discipline and temperament also predicted internalizing problems, with

negative parenting predicting depression only for difficult children. The

authors posited that children with difficult temperament were more likely

to elicit harsh parenting, such that difficult temperament served as a demand characteristic, eliciting negative parenting and perpetuating negative

adjustment outcomes for the child. The data were also consistent with the

hypothesis of differential susceptibility, in that difficult children were more

susceptible to the influence of parental discipline than were their nondifficult peers.

In another concurrent study of pre-adolescent boys, Colder, Lockman,

and Wells (1997) reported numerous interactions between parenting and

child temperament. Sixty-four 4th and 5th grade boys and their parent completed questionnaires. Child activity level was rated by the parent and child

fearfulness was rated by the parent and child. Parents reported their own involvement, monitoring and harsh discipline. Child aggression was reported

by the childÕs teacher and child depression was reported by the child.

636

K.C. Gallagher / Developmental Review 22 (2002) 623–643

Parenting was related to child pathology in interaction with distinct characteristics of child temperament. Poor parental monitoring was related to

child aggression for children high in activity level, but not for children with

low and moderate activity level. Parental harsh discipline predicted child aggression in children moderate or high in fearfulness, but not in children low

in fearfulness. Harsh discipline also predicted child depression, but only

when children were highly fearful. Both high and low levels of parental involvement predicted child depression when children were moderately fearful, but not when children were low or high in fearfulness, suggesting that

high involvement may be intrusive for children who are average in their temperamental fearfulness.

While the findings of both Blackson et al. (1996) and Colder et al. (1997)

were complex, their specificity regarding temperament and parenting characteristics render a pattern consistent with bioecological theory. Parenting

processes characterized as highly controlling and harsh predicted negative

adjustment outcomes, but only for boys who exhibited temperament characteristics associated with risk. Additionally, temperamentally negative boys

were more susceptible to parenting processes in relation to adjustment outcomes, supporting the differential susceptibility hypothesis.

In research drawing on data from two longitudinal samples, Bates, Pettit,

Dodge, and Ridge (1998) explored the interaction of maternal parenting and

child temperament in relation to externalizing problems. Bates and colleagues examined temperamental resistance to control, defined as child behavior that is typically impulsive and uncontrollable, ignoring or reacting

angrily to outside guidance (Bates et al., 1998). Mothers of Sample I children (N ¼ 90) completed temperament questionnaires when the children

were 13- and 24-months old, while mothers of Sample II children

(N ¼ 156) completed retrospective versions of the same temperament measure when the children were 5-years old. Maternal restrictive control was observed in the home, when infants were 6-, 13-, and 24-months old with

Sample I and at 5-years old with Sample II. High ratings of restrictive control described maternal attempts to manage difficult child behavior using restrictions, threats and correction. Mothers and teachers reported child

externalizing behaviors several times between 7- and 11-years old.

Maternal restrictive control interacted with temperament in prediction of

later externalizing problems. Low maternal restrictive control predicted

more externalizing behavior, but only for children high in resistance to control. High parental restrictive control predicted low externalizing for children high in resistance, but not for children low in resistance to control.

In both cases, negative temperament was more amenable to socialization influences of parenting than non-negative temperament. Mothering that was

higher in power predicted better adjustment for children who were more resistant to control. Bates et al. (1998) posited that more controlling maternal

care helped resistant children develop internal controls.

K.C. Gallagher / Developmental Review 22 (2002) 623–643

637

The findings of Bates et al. (1998) converge with those of Park et al.

(1997), providing support for the differential susceptibility hypothesis.

Children with negative temperament characteristics were more susceptible

parental control in relation to adjustment outcomes. Parental control interacted with negative characteristics of child temperament to constrain the

potential expression of negative behavior at later points of development.

Unlike the findings of Blackson et al. (1996) and Colder et al. (1997), higher parental control was related to more positive child outcomes. Bates

et al. (1998) examined parental control as distinct from harshness, and examined change over time, differences that may have accounted for the discrepancy.

Conclusions: A conditional model of parenting influence

Despite contentions to the contrary (see Harris, 1995), there is evidence

that parenting bears considerable import for childrenÕs adjustment (Collins

et al., 2000; Vandell, 2000), and emerging research suggests that parental socialization plays a distinct role for children of different temperaments. One

of the primary goals of this review was to identify an appropriate theoretical

foundation for this emergent line of research. Several considerations provide

guidance for ongoing research.

Developmental considerations

Positive parenting varies in relation to the childÕs developmental level, as

well as in relation to the childÕs temperament. In early childhood, responsive, low-power mothering predicted positive adjustment only when children

demonstrated more negative emotionality. Both intrusive and sensitive parenting were associated with less shyness in the preschool years, for children

that were highly fearful as infants. While Kagan (1997) suggested that more

socially demanding parental control decreases later shyness for fearful children, attachment theorists posit that all children, including fearful ones,

demonstrate better social and peer skills as a result of a caregiver–child relationship based on sensitive and responsive parenting (Bretherton, Biringen, & Ridgeway, 1991; Sroufe, 1985).

In middle childhood and adolescence, harsh parenting had deleterious effects for children who demonstrated negative temperament characteristics;

however, high parental control that was not harsh had positive effects on adjustment when children were temperamentally negative. Higher parental

control than previously posited may facilitate adjustment in school-age children who are fearful or resistant to control.

Parenting proximal processes did not interact with child temperament in

studies limited to infancy. Kochanska (1997) suggested that main effects of

638

K.C. Gallagher / Developmental Review 22 (2002) 623–643

parenting and temperament are more visible in earlier development, and

that interactions are more common as development proceeds. This hypothesis is consistent with bioecological theory, in that processes and interactions

are posited to grow more complex over time (Bronfenbrenner & Morris,

1998). More longitudinal data will be necessary to test this position. It is

clear that the socialization needs of children change as development progresses; further research is needed to examine parenting and temperament

interaction at different developmental periods.

Methodological considerations

Several methodological considerations could be incorporated into ongoing research, involving variable specificity, research design and analytical strategies. One strategy would be to test the different aspects of harsh

parenting in interaction with qualities of temperament as related to adjustment. Parental high control may predict positive adjustment when children are highly resistant to control, but predict negative adjustment

when children are highly fearful. Another strategy might examine different

levels and types of parental monitoring in interaction with temperament.

High parental monitoring may not be important for fearful children

who are less likely to take risks. However, it could be expected to interact

with high activity or low fearfulness to constrain dangerous risk-taking

behavior. A fine-grained approach to the examination of interaction of

temperament and parenting could provide insight beyond consideration

of global constructs such as ‘‘difficult’’ temperament and ‘‘negative’’ parenting.

The interaction of parenting and temperament could also be investigated

using experiments. Different parenting techniques could be taught and emphasized to groups of parents, with groups randomly assigned, balanced in

terms of child temperament characteristics, and including control groups.

Other factors could include child gender, father and mother, and remote

variables of parenting, such as social support and parent personality. Using

pre- and post-measures of child adjustment, the researcher could tease out

the processes via which children with particular temperament characteristics

are parented most effectively.

Intervention was a powerful factor in experimental work of van den

Boom (1994). Low-SES mothers of highly negative infants participated in

a skill-based program focusing on improving perception, interpretation,

and responsiveness to their infantÕs cues. When the children were 9-months

old, the mothers of the intervention groups were more responsive, stimulating and attentive than the control mothers, and their children were more sociable and less negative than the controls. When the children were a year

old, the intervention infant infants were more likely to be securely attached than the controls. Experimental research implementing intervention

K.C. Gallagher / Developmental Review 22 (2002) 623–643

639

strategies with both negative and non-negative infants could test both the

bioecological framework and differential susceptibility hypothesis.

A moderator model tests hypotheses of conditional influence; however,

statistical interactions allow us to look at the effects only superficially (Rutter & Pickles, 1991), and to speculate regarding causal mechanisms. Baron

and Kenny (1986) suggested using mediated moderation, a combined approach of investigation, to address this limitation. Using a path analytic

framework, moderators of an association are identified, and causal paths

are explored to identify variables influencing the moderatorÕs effect on the

predictor.

Attachment security, differential susceptibility, parental attitudes or experience, and developmental stage, are factors that may mediate the interaction of parenting and child temperament. As an example, a childÕs

internal working model of self and parent could facilitate the interactive influence of parenting and temperament on adjustment. A parent might exert

control by encouraging a fearful child to approach playmates, respond politely to adults, and even defend play territory from aggressive children. If

the child is securely attached to the parent, and has a working model that

provides a sense of security and self-worth, the child may not exhibit

poorer social adjustment, typically associated with fearfulness. A mediated

moderator approach could enrich the study of parenting–temperament interaction.

Theoretical considerations

Under the umbrella of the Process–Person–Context–Time model, we can

begin to evaluate the structure of the childÕs developmental milieu. Parenting, viewed as a process involving the child and parent reciprocally, combined with elements of Context, and observed over Time, may provide a

richer understanding of ‘‘the ecology of developmental processes’’ (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998). This review focused on the Process and Person aspects of the PPCT model; however, Context and Time should also be

considered. Culture, economic status, family structure and neighborhood

are all elements of Context that interact with parenting Processes, Person

and Time to sculpt the course of a childÕs life. In some cultures (e.g., some

Asian) child inhibition, or shyness, is not considered a negative temperament characteristic. For children raised in such cultural contexts, parenting

processes may not influence the course of inhibition. The child might demonstrate shyness in school, but would not necessarily exhibit negative adjustment. Research authentic to bioecological systems theory must consider

appropriate elements of Context.

Other elements of Context that may interact with processes of parenting

and child temperament include political conditions, social policy, and societal attitudes. In extreme contexts (e.g., war, famine) different parenting and

640

K.C. Gallagher / Developmental Review 22 (2002) 623–643

temperament characteristics may be associated with child adjustment. More

parental control may be necessary in dangerous environments. Negative

temperament characteristics may not be amenable to change when they

are adaptive, as in a famine (see DeVries, 1984). The interaction of parenting

processes and child temperament need to be explored in extreme contexts.

Time also needs to be considered in research that examines the interaction of parenting and temperament. Research should be longitudinal when

possible (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998; Lerner, 1998; Wachs, 1991), in

order to address changes over time in children and parentsÕ behavior. The

historical milieu in which children develop should also be considered.

The differential susceptibility hypothesis (Belsky, 1997) is supported in

the literature reviewed, as children with different temperament profiles varied in their sensitivity to parental influence. Children who were more negative in their affect and/or withdrew from stimuli were more vulnerable to the

effects of parenting. Children higher in negative emotion, fearfulness or activity level were more susceptible to parental control and responsiveness

than children who were less fearful, active or negative. Effects were evident

in prosocial behavior and behavior problems, beyond the influences of temperament and parenting alone. Belsky suggested that heritability estimates

could help to test this hypothesis further. If high or low levels of some

‘‘behavioral style’’ were shown to be less heritable than traits at other levels,

more environmental contribution to the high and low levels could be assumed, indicating greater amenability to influences, such as parenting proximal processes.

Ultimately, a model should advance understanding of developmental

processes (Wachs, 1991). Exploring the interactive effects of Person (temperament) and Process (parenting) as related to child adjustment, and extending research to include elements of Context and Time, we pursue the

ultimate goal: better understanding of the characteristics and circumstances

of parenting that promote positive child adjustment for children of different

temperaments.

References

Ainsworth, M. D., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment:

Assessed in the strange situation and at home. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social

psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182.

Bates, J. E. (1989). Applications of temperament concepts. In G. A. Kohnstamm, J. E. Bates, &

M. K. Rothbart (Eds.), Temperament in childhood (pp. 321–355). New York: Wiley.

Bates, J. E., Maslin, C. A., & Frankel, K. A. (1985). Attachment security, mother–child

interaction and temperament as predictors of behavior-problem ratings at age three years.

In I. Bretherton & E. Waters (Eds.), Growing points of attachment theory and research (Vol.

50, pp. 167–193). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

K.C. Gallagher / Developmental Review 22 (2002) 623–643

641

Bates, J. E., Pettit, G. S., Dodge, K. A., & Ridge, B. (1998). Interaction of temperamental

resistance to control and restrictive parenting in the development of externalizing behavior.

Developmental Psychology, 34, 982–995.

Baumrind, D. (1979). The development of instrumental competence through socialization. Paper

presented at the Minnesota symposia on child psychology, Minneapolis, MN.

Baumrind, D. (1991). Effective parenting during the early adolescent transition. In P. A. Cowan

& E. M. Hetherington (Eds.), Family transitions (pp. 111–163). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence

Erlbaum.

Bell, R. Q. (1968). A reinterpretation of the direction of effects in studies of socialization.

Psychological Review, 75, 81–95.

Belsky, J. (1997). Variation in susceptibility to environmental influence: An evolutionary

argument. Psychological Inquiry, 8(3), 230–235.

Belsky, J. (2001). Differential susceptibility to rearing influence: An evolutionary

hypothesis and some evidence. Unpublished manuscript, Birkbeck College, University

of London.

Belsky, J., Fish, M., & Isabella, R. (1991). Continuity and discontinuity in infant negative and

positive emotionality: Family antecedents and attachment consequences. Developmental

Psychology, 27(3), 421–431.

Belsky, J., Hsieh, K., & Crnic, K. (1998). Mothering, fathering, and infant negativity as

antecedents of boysÕ externalizing problems and inhibition at age 3: Differential susceptibility to rearing influence? Development and Psychopathology, 10, 301–319.

Blackson, T. C., Tarter, R. E., & Mezzich, A. C. (1996). Interaction between childhood

temperament and parental discipline practices on behavioral adjustment in preadolescent

sons of substance abuse and normal fathers. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse,

22(3), 335–348.

Bretherton, I., Biringen, Z., & Ridgeway, D. (1991). The parental side of attachment. In K.

Pillemer & K. McCartney (Eds.), Parent–child relations throughout life (pp. 1–24). Hillsdale,

NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University Press.

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Crouter, A. C. (1983). The evolution of environmental models in

developmental research. InP. H. Mussen (Ed.), History, theory and methods (Vol. 1, (4th

ed.., pp. 357–414). New York: Wiley.

Bronfenbrenner, U. & Morris, P. (1998). The ecology of developmental processes. In W.

Damon (Series Ed.), & R. M. Lerner (Vol. Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 1.

Theoretical models of human development (5th ed., Vol. 1, pp. 993–1028). New York: Wiley.

Chamberlain, P., & Patterson, G. R. (1995). Discipline and child compliance in parenting. In

M. Bornstein (Ed.), Applied and practical parenting (Vol. 4, pp. 205–225). Mahwah, NJ:

Lawrence Erlbaum.

Chess, S., & Thomas, A. (1989). Issues in the clinical application of temperament. In G. A.

Kohnstamm, J. E. Bates, & M. K. Rothbart (Eds.), Temperament in childhood (pp. 377–

403). New York: Wiley.

Colder, C. R., Lockman, J. E., & Wells, K. C. (1997). The moderating effects of childrenÕs fear

and activity level on relations between parenting practices and childhood symptomatology.

Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 25(3), 251–263.

Collins, W. A., Maccoby, E. E., Steinberg, L., Hetherington, E. M., & Bornstein, M. (2000).

Contemporary research on parenting: The case for nature and nurture. American

Psychologist, 55(2), 218–232.

Crockenberg, S. B. (1981). Infant irritability, mother responsiveness, and social support

influences on the security of infant–mother attachment. Child Development, 52, 857–865.

DeVries, M. W. (1984). Temperament and infant mortality among the Masai of East Africa.

American Journal of Psychiatry, 14(10), 1189–1194.

642

K.C. Gallagher / Developmental Review 22 (2002) 623–643

Early, D. M., Rimm-Kaufman, S. E., Cox, M. J., & Saluja, G. (1999, April). Predicting

children’s wariness in the transition to kindergarten. Poster session presented at the Society

for Research in Child Development, Albuquerque, NM.

Egeland, B., & Sroufe, L. A. (1981). Developmental sequelae of maltreatment in infancy. In R.

Rizley & D. Cicchetti (Eds.), Developmental perspectives in child maltreatment (pp. 77–92).

San Francisco: Joffey-Bass.

Harris, J. R. (1995). Where is the childÕs environment? A group socialization theory of

development. Psychological Review, 102(3), 458–489.

Hershberger, S. L. (1994). Genotype–environment interaction and correlation. In J. C. DeFries,

R. Plomin, & D. W. Fulker (Eds.), Nature and nurture during middle childhood (pp. 281–

294). Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers.

Hinde, R. A. (1989). Temperament as an intervening variable. In G. A. Kohnstamm, J. E.

Bates, & M. K. Rothbart (Eds.), Temperament in childhood (pp. 27–33). New York:

Wiley.

Kagan, J. (1994). GalenÕs prophecy: Temperament in human nature. New York: Harper Collins.

Kagan, J. (1997). Temperament and reactions to unfamiliarity. Child Development, 68(1), 139–

143.

Kochanska, G. (1995). ChildrenÕs temperament, mothersÕ discipline, and security of attachment:

Multiple pathways to emerging internalization. Child Development, 66, 597–615.

Kochanska, G. (1997). Multiple pathways to conscience for children with different temperaments: From toddlerhood to age 5. Developmental Psychology, 33(2), 228–240.

Kochanska, G. (1998). Mother–child relationship, child fearfulness, and emerging attachment:

A short-term longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 34(3), 480–490.

Lerner, R. M. (1998). Theories of human development: Contemporary perspectives. In W.

Damon (Series Ed.), & R. M. Lerner (Vol. Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 1.

Theoretical models of human development (5th ed., pp. 1–24). New York: Wiley.

Maccoby, E. M. (1980a). Child rearing practices and their effects. In J. Kagan (Ed.), Social

development: Psychological growth and the parent–child relationship (pp. 367–410). New

York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Maccoby, E. M. (1980b). Social development: Psychological growth and the parent–child

relationship. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Magnusson, D. & Stattin, H. (1998). Person–context interaction theories. In W. Damon (Series

Ed.), & R. M. Lerner (Vol. Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 1. Theoretical models of

human development (5th ed., Vol. 3, pp. 685–759). New York: Wiley.

Mangelsdorf, S., Gunnar, M., Kestenbaum, R., Lang, S., & Andreas, D. (1990). Infant

proneness-to-distress temperament, maternal personality, and mother-infant attachment:

Associations and goodness-of-fit. Child Development, 61, 820–831.

Martin, R. P. (1989). Activity level, distractibility, and persistence: Critical characteristics in

early schooling. In G. A. Kohnstamm, J. E. Bates, & M. K. Rothbart (Eds.), Temperament

in childhood (pp. 451–461). New York: Wiley.

Park, S.-Y., Belsky, J., Putnam, S., & Crnic, K. (1997). Infant emotionality, parenting, and

3-year inhibition: Exploring stability and lawful discontinuity in a male sample. Developmental Psychology, 33(2), 218–227.

Patterson, G. R., Reid, J. B., & Dishion, T. J. (1984). Family interaction: A process model of

deviancy training. Aggressive Behavior, 10, 253–257.

Plomin, R., & Daniels, D. (1984). The interaction between temperament and environment:

Methodological considerations. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 30(2), 149–162.

Prior, M. R., Sanson, A. V., & Oberklaid, F. (1989). The Australian temperament project. In G.

A. Kohnstamm, J. E. Bates, & M. K. Rothbart (Eds.), Temperament in childhood (pp. 537–

554). New York: Wiley.

Rothbart, M. K. (1989). Temperament and development. In G. A. Kohnstamm, J. E. Bates, &

M. K. Rothbart (Eds.), Temperament in childhood (pp. 247–287). New York: Wiley.

K.C. Gallagher / Developmental Review 22 (2002) 623–643

643

Rothbart, M. K., & Bates, J. E. (1998). Temperament. In N. Eisenberg (Ed.), Social, emotional

and personality development (Vol. 3, 5th ed., pp. 105–176). New York: Wiley.

Rubin, K. H., Stewart, S. L., & Chen, X. (1995). Parents of aggressive and withdrawn children.

In M. Bornstein (Ed.), Children and parenting (Vol. 1, pp. 255–284). Mahwah, NJ:

Lawrence Erlbaum.

Rutter, M. (1997). Clinical implications of attachment concepts. In L. Atkinson & K. J. Zucker

(Eds.), Attachment and psychopathology (pp. 17–46). New York: Guilford.

Rutter, M., & Pickles, A. (1991). Person–environment interactions: Concepts, mechanisms, and

implications for data analysis. In T. D. Wachs & R. Plomin (Eds.), Conceptualization and

measurement of organism–environment interactions (pp. 105–141). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Sanson, A., & Rothbart, M. K. (1995). Child temperament and parenting. In M. Bornstein

(Ed.), Applied and practical parenting (Vol. 4, pp. 299–321). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence

Erlbaum.

Sroufe, L. A. (1985). Attachment classification from the perspective of infant–caregiver

relationships and infant temperament. Child Development, 56, 1–14.

Stanhope, L. N. (1999, April). Preschoolers’ sharing as related to birth order, temperament, and

parenting styles. Poster session presented at the biennial meeting of the Society of Research

in Child Development, Albuquerque, NM.

Suess, G. J., Grossman, K. E., & Sroufe, L. A. (1992). Effects of infant attachment to mother

and father on quality of adaptation in preschool: From dyadic to individual organization of

self. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 15, 43–65.

Thomas, A. (1984). Temperament research: Where we are, where we are going. Merrill-Palmer

Quarterly, 30(2), 103–109.

Vandell, D. L. (2000). Parents, peer groups, and other socializing influences. Developmental

Psychology, 36(6), 699–710.

van den Boom, D. C. (1989). Neonatal irritability and the development of attachment. In G. A.

Kohnstamm, J. E. Bates, & M. K. Rothbart (Eds.), Temperament in childhood (pp. 299–

317). New York: Wiley.

van den Boom, D. C. (1994). The influence of temperament and mothering on attachment and

explorations: An experimental manipulation of sensitive responsiveness among lower-class

mothers and irritable infants. Child Development, 65, 1457–1477.

Wachs, T. D. (1991). Synthesis: Promising research designs, measures and strategies. In T. D.

Wachs & R. Plomin (Eds.), Conceptualization and measurement of organism–environment

interaction (pp. 162–182). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Wachs, T. D., & Plomin, R. (1991). Overview of current models and research. In T. D. Wachs &

R. Plomin (Eds.), Conceptualization and measurement of organism–environment interaction

(pp. 1–8). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.