Teacher`s pack - English Touring Opera

Teacher’s Pack

SHACKLETON’S

CAT

A new opera for children aged 7-11

This pack was written and compiled by Talia Lash at English Touring Opera with Tim Yealland (ETO) and

Naomi Chapman, Heather Lane and Naomi Boneham (Scott Polar Research Institute, University of

Cambridge). Cover image by Jude Munden.

We would like to thank Roderic Dunnett and the James Caird Society, Joseph Spence, Calista Lucy, Peter

Jolly, Richard Mayo and Simon Yiend at Dulwich College, John Blackborow, Sir James Perowne, Alexandra

Shackleton, Angela Montfort Bebb, Jim Mayer, Briony Gimson, Jim Mayer, Rebecca Moffatt, Steve

Hawkins and Tom Spickett.

Shackleton’s Cat Creative Team:

Composer

Russell Hepplewhite

Writer and Director

Tim Yealland

Designer

Jude Munden

ETO’s production of Shackleton’s Cat has been made possible thanks to the generous support of: through the Strategic Touring Fund

Austin and Hope Pilkington Trust

D’Oyly Carte Charitable Trust

Joyce Fletcher Charitable Trust

Lord and Lady Lurgan Trust

The Sackler Trust

And the 53 generous supporters who donated to this project through the Big Give Christmas

Challenge 2014

©

All rights reserved 2015

Shackleton’s Cat

Teacher’s Pack

Introduction

Shackleton’s

voyage

Key

characters

in

the

opera

Dogs

on

the

Endurance

Antarctic

facts

Interview

with

Tim

Yealland

A

note

from

the

composer

Classroom

activity

ideas

Artists

Song

words

Sheet

music

Further

information

4

5

7

10

11

14

15

16

26

31

32

43

Photo licensed with the permission of the Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge

Introduction

Each year, English Touring Opera commissions and produces a brand new opera for children, which tours around the UK, performing in school halls and intimate venues.

Shackleton’s Cat is the latest in a line of operas especially created for children in primary schools, as well as for family audiences.

This strand of ETO’s work is intended very much to stimulate the learning of young people we work with, and to engage with them on many different levels.

We see these pieces as a real opportunity to partner with schools, and to encourage an expansive view of the interest of both the arts and, in

this case, history and geography.

We are thrilled that the Scott Polar Research Institute have contributed their expertise and resources to this project, and hope that teachers and children will find the historical information

and classroom activities in this pack both informative and inspiring.

ETO has now created quite a number of operas on this scale (including Borka: the goose with no feathers and the award ‐ winning Laika the Spacedog ) so it is fair to say that we have developed a house style for them.

This is a style which uses music, dialogue, movement, puppets, design, and even film in quite a free way.

A key element is interaction: the audience always has a part in the story ‐ telling and some of the singing.

We hope the pieces we make are quite the opposite from opera’s awful and stuffy reputation, because for us it can be liberating, fun and supremely

expressive.

4

Images from Laika the Spacedog , 2013, and Borka, 2014

Audience participation is integral to the show, so we encourage teachers to prepare three songs with your children, so that they can sing them with us during the performance.

The words and

music are supplied in this pack, along with a CD to help you learn.

The opera itself lasts about an hour, and is suitable for children aged 7–11 years.

The piece and this pack are covered by copyright and all rights are reserved.

We look forward to bringing Shackleton’s Cat to you and hope you enjoy the show!

Shackleton’s Imperial Trans ‐ Antarctic ( Endurance) Expedition left London in the summer of 1914.

His plan was to cross Antarctica from the Weddell Sea to the South Pole then on to the Ross Sea.

This

across Antarctica is 1,800 miles.

Shackleton named his ship Endurance after his family motto

Vincimus’: by endurance we conquer.

On board were all the supplies that they would need

their expedition.

they arrived in Antarctica, winter was

and ice was beginning to form on top

the sea.

Shackleton tried to find a safe place to

anchor but it was too late, the Endurance

trapped in the sea ice.

The ice was

and it was taking the Endurance with it,

and pulling her further and further from

The crew unpacked as much of the

as they could before the Endurance

crushed by ice.

They then watched as the

slowly sank to the bottom of the sea.

Shackleton’s voyage

Photo: Frank Hurley.

Licensed with the permission of the Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge

6

Pulling three lifeboats full of equipment, the men walked across the ice looking for a safe place to set up camp. After four months camping on the ice, the ice began to break up, so the men got in to the lifeboats and headed towards the nearest land, Elephant Island. Everyone was overjoyed to have found land, fresh water and plenty of Elephant Seal meat to eat; many of the men were in a desperate state.

The problem was that they were still hundreds of miles from people who could help them. One of the lifeboats would need to go and get help.

Shackleton’s new plan was to sail 800 miles to South Georgia across some of the stormiest seas on the planet. For six men to make this journey in a small boat would be extremely dangerous, but as long as the sea was clear of ice and they had the wind behind them they stood a chance. They chose the largest lifeboat, the James Caird . McNish, the carpenter, spent the days before leaving making her more seaworthy. He made a cover for the boat from canvas sail material so that she wouldn’t fill up with water in the stormy seas. They packed rations for one month, raised the sail and rowed away from Elephant Island in the direction of

South Georgia.

South Georgia is an island only 100 miles long and 23 miles wide and it is 800 miles away from Elephant Island. If they missed South Georgia they would be lost in the vast Atlantic Ocean.

Shackleton’s Captain, Frank Worsley, was a brilliant navigator so he was in charge of sailing the James

Caird.

Meanwhile on Elephant Island the remaining men waited anxiously – would Shackleton ever return?

On board the James Caird , the next two weeks were ‘a daily struggle to keep (them)selves alive’ in gale force winds and huge waves. One man held the rudder and another the sail while a third baled water out of the little boat. Meanwhile the other three crawled into their soaking sleeping bags at the bottom of the boat among the rocks and sandbags. The men were so thirsty that their tongues swelled up.

Eventually South Georgia came into sight – stormy weather had carried them around the island to rocky shores. It took two days for them to land. It was now early winter and a range of mountains separated them from the whaling station on the south side of the island.

The journey had been extremely difficult and the men were now very weak. Three men were too ill to climb the mountains so camped in a cave on the beach. At 2 o’clock in the morning of Friday 19 th

May

1916 Shackleton, Worsley and Crean began the first ever crossing of South Georgia. By the light of a full moon they saw snow-slopes, high peaks and cliffs. A day later they staggered in to the whaling station, and could now start to save the other men stuck on Elephant Island. Again and again the stormy seas of the Southern Ocean stopped Shackleton from reaching Elephant Island. It was only on his fourth attempt that he was finally able to rescue the men on August 30 th

1916. Amazingly, all 28 men survived.

Key characters in the opera

There were 28 men in Shackleton’s Endurance crew. Unfortunately we couldn’t include them all in our opera. The following key characters appear in Shackleton’s Cat to tell the story of what happened. The children in the audience play the rest of the crew.

Frank Worsley (1872–1943) was a sailor from New Zealand who served as the captain of the

Endurance under Shackleton. Famously he dreamt one night of icebergs floating down Burlington Street in London, and when he went to the street the next morning saw the sign for Shackleton’s expedition, and promptly signed up as ship’s captain. His navigational skills, particularly his use of the sextant, were incredible, and saved the men from certain death. On the James

Caird lifeboat he managed to find the island of South Georgia in the middle of the vast ocean, and with very few glimpses of the sun and the stars, the essential navigational aids. He served in the navy in the First World War, sinking a German submarine in

1917. He was known as Wuzzles .

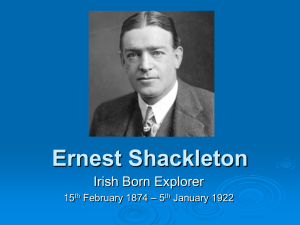

Sir Ernest Shackleton (1874–1922) was an Irishman, brought up largely in south London, educated at Dulwich College, and known today as perhaps the greatest of all the polar explorers.

Known as The Boss , he led three British expeditions to the

Antarctic, and was knighted for his feats, which included reaching a point just 100 miles short of the pole, the furthest anyone had been in 1909. His greatest achievement was the rescue of all 28 men on the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, against all the odds. It is thought of as one of the greatest examples of leadership in history. He had problems with money at home, and never settled when he was not in the middle of an adventure. He died on South Georgia in 1922, at the beginning of a new expedition, and is buried there.

Frank Wild (1873–1939) was a Yorkshireman who went on five south polar expeditions and served with Captain Scott as well as with

Shackleton. Known as Frankie, he was second-in-command on the

Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition. He was left in charge of the men on Elephant Island when Shackleton took Worsley, McNish and a few others to get rescue from South Georgia. He had an exceptionally cool head and is remembered today as one of the greatest of the polar explorers, alongside Shackleton and Scott. He was with Shackleton in

South Georgia in 1922 when The Boss died. He served for the British in

Russia in the last years of the First World War, and subsequently became a farmer in Africa, where he died.

7

8

Harry McNish (1874 –1930), sometimes spelt McNeish, and known as

Chippy , was the carpenter on the Imperial Trans ‐ Antarctic Expedition.

His skills became essential after the Endurance broke up in the ice, and he was responsible for fitting out the lifeboats that would save the men on their journey to Elephant Island, and then on the final astonishing journey to South Georgia, a trip he was part of along with only five others.

He had a cat called Mrs Chippy, who turned out to be a boy cat.

McNish could be opinionated, and he and Shackleton never quite got on, a fact that is perhaps reflected in the refusal to award him a Polar Medal.

He died in New Zealand, penniless.

A statue of the cat was recently added to his grave.

McNish's grandson

Tom, who lives in England, was delighted about this and felt his grandfather would have been pleased.

He said: “I think the cat was more important to him than the

Polar Medal.”

Perce Blackborow (1896–1949) was from Wales.

He was shipwrecked as a very young man – along with his friend William Bakewell – on the coast of Uruguay, and they subsequently travelled to Buenos Aires looking for a job.

The Endurance was in the port and they both tried to find employment as members of the crew.

Bakewell was successful, but Perce was too young.

Perce took matters into his own hands by climbing onboard as a stowaway, to be discovered a few days later when the boat was already at sea.

He was put to work in the kitchen,

and was good enough to be signed on as a member of the crew, becoming ship’s steward.

Well ‐ liked and with an easy ‐ going manner he suffered from terrible frostbite and gangrene, and had some of his toes amputated on Elephant Island, an operation which undoubtedly saved his life.

Another crew member described his reaction to the operation:

“The poor beggar behaved splendidly and it went without a hitch…

When Blackborow came to, he was cheerful as anything and started joking directly.”

Photo licensed with permission of Scott

Polar Research Institute, University of

Cambridge

Mrs Chippy was the tabby cat taken on board the Endurance by the carpenter Harry McNish.

Carpenters are often called Chippy, hence the name given to the cat.

It was a month into the voyage when Mrs Chippy was discovered to be a boy cat.

The crew loved Mrs Chippy for his friendliness and his character (he was unafraid of the dogs on deck) and for his ability to walk along the ship's inch ‐ wide rails in even the roughest seas.

After the ship was destroyed,

Shackleton ordered that Mrs Chippy along with some of the dogs be shot.

Shackleton felt that it was impossible to feed the animals.

It seems that McNish felt the loss so badly he never forgave Shackleton, and that this event led to some friction between the two men.

In 2004 a bronze statue of the cat was placed on McNish's grave in New

Zealand.

In our production, Mrs Chippy is played by a puppet, handmade by our designer, Jude Munden.

Here are some pictures of her creation process.

9

Dogs

on

the

Endurance

Although they do not feature prominently in our opera, the 69 dogs that accompanied the men on

the Endurance mission were essential to the expedition.

Shackleton had originally planned to bring over 100 dogs, and these were shipped over from Canada and arrived at Millwall docks in London on 14 July 1914.

They were mostly mongrels bred with huskies.

Their job on the expedition was to pull the sledges carrying all of the equipment across the ice to the South Pole.

When the Endurance got trapped in the ice and started to drift, and the mission couldn’t continue, the dogs helped keep the men occupied and entertained.

Shackleton organised six sledging teams, and the men and their dogs would race each other.

After some time drifting, it became clear that the expedition was not going to reach the South Pole, and Shackleton had to think about what to do next.

The dogs were eating more food than the crew, and saving the men became the priority.

Between January and March 1916 all the dogs were shot, in order to preserve rations for the men.

Some of the dogs were eaten in order to survive.

While it was necessary to do this, the men were sad that they had been forced to end the dogs’ lives in this way.

Frank Hurley wrote: “ I have known many men who I would rather have shot, than these dogs”.

10

Some of the dogs.

Photo courtesy of the James Caird Society

Names of 66 of the dogs:

Alti

Amundsen

Dismal

Elliott

Blackie

Bob

Bo’sun

Bristol

Brownie

Buller

Fluff

Gruss

Hercules

Jamie

Hackenschmidt

Bummer

Caruso

Chips

Jasper

Jerry

Judge

Luke

Lupoid

Mack

Martin

Mercury

Noel

Paddy

Peter

Roger

Roy

Rufus

Rugby

Sadie

Sailor

Saint

Sally

Sammy

Samson

Sandy

Satan

Shakespeare

Side Lights

Simian

Slippery Neck

Slobbers

Snapper

Snowball

Soldier

Songster

Sooty

Spider

Split Lip

Spotty

Steamer

Steward

Stumps

Sub

Sue

Surly

Swanker

Sweep

Tim

Upton

Wallaby

Wolf

Antarctic facts

7 Antarctica is at the bottom of our planet and the

Arctic is at the top.

They are the polar areas that are covered in snow and ice.

7 In the polar regions, the sun never rises for half of the year and for the next half year it never sets.

Even in the summer, the sun’s rays are so weak that it never warms up and in Antarctica it is too cold for trees or grass to grow.

Summer in the Antarctic is during the winter in the UK, and the Antarctic winter is during our summer.

7 Antarctica is the coldest place on the planet and temperatures often get down to ‐ 60°C.

At ‐ 25°C steel becomes brittle and at ‐ 40°C skin that’s unprotected freezes.

7 Antarctica is a huge continent much bigger than the USA and thousands of miles from the UK.

The seas that surround Antarctica freeze in the winter but in summer, penguins, gulls, whales and seals live around the coast diving for food among the ice floes.

Near the coast are huge mountains, and beyond the mountains is a high polar plateau (large flat space).

On the plateau it is so cold and bleak that wild animals cannot survive there.

In about the middle of the plateau is an area called the South Pole and these days a few people, doing scientific work, live there.

In 1914 very little was known about this incredibly harsh yet incredibly beautiful continent.

Only a few people get to visit Antarctica and most of

them want to go back.

7 About 99% of Antarctica is covered with a huge ice sheet.

It is the largest single mass of ice on Earth and is bigger than the whole of Europe.

The ice sheet averages 2,450 metres deep and holds about 70% of the world’s fresh water.

7 In winter, much of the surrounding ocean freezes over.

With this extra winter sea ‐ ice, Antarctica almost doubles in size.

11

7 Antarctica is so dazzlingly white because of the snow, it is possible to get ice blindness from looking at the whiteness.

If you took a picture with flash on Antarctica without protecting your eyes, you would be blind for 5 ‐ 6 minutes, which is long enough to freeze!

Shackleton’s men and modern explorers in

Antarctica have to make sure they wear goggles to protect their eyes.

The goggles the men on Shackleton’s expedition wore.

Photo courtesy of Scott Polar Research Institute.

7 Although it is one of the coldest regions in the world, there is an abundance of wildlife in the

Antarctic coastal regions.

It was this abundance that allowed Shackleton’s men to survive for so many

months on the ice, eating a diet of penguins, and when they could catch them, seals.

They also used the skins as fuel for their stove.

Seals

Leopard Seal

Crabeater Seal

Fur Seal

Elephant Seal

Penguins

Emperor Penguin

Chinstrap Penguin

Adélie Penguin

Gentoo Penguin

Whales

Killer Whale

Humpback Whale

Finner Whale

Blue Whale

Other birds

Petrels

Albatrosses

Skuas

7 When it is really cold, penguins stand on their heels holding their toes up.

They use their tails to support themselves so they don’t fall over backwards.

Their stiff tail feathers lose no heat, so the penguins have as little of their bodies touching the freezing ice as possible.

7 Penguins hunt for food by diving underwater and swallowing their prey.

They can hold their breath underwater for almost 20 minutes!

7 Penguin poo can be pink or orange (as they mainly eat krill, a kind of shrimp, which is pink), and you

can see it from space!

7 Pack ‐ ice is the sea ice in the Arctic and Antarctic regions.

Antarctica is a solid land mass surrounded by sea which freezes into pack ‐ ice near the coast.

During the Antarctic summer months of December,

January and February (our winter months) the pack ‐ ice is thin enough to get through with the right ship.

Sometimes there are gaps in the pack ‐ ice called ‘leads’ and in Shackleton’s day someone would climb the rigging (a net made from rope) to the crow’s nest (a kind of balcony high on the ship’s mast) and look for these gaps.

It was like looking over a vast jigsaw.

Where there were no gaps ships would ram the pack to break through.

If the pack was too thick to get through, ships became trapped.

They then drifted in the pack which slowly moves due to wind and currents in the sea beneath.

The floes (huge slabs of floating ice) grind against each other and the wooden ships of Shackleton’s day could easily be crushed between them.

This was always a danger in the dreaded Weddell Sea which is in a bay bigger than

France.

The pack gets trapped in the bay and so the Weddell Sea fills with billions of tonnes of ice, always on the move and under massive pressure.

The moving pack makes weird, scary noises.

13

Interview

with

Tim

Yealland,

writer

and

director

of

Shackleton’s Cat

Why did you want to write an opera about this story?

It is now 100 years since the famous expedition.

If Shackleton’s journey had gone according to plan, and if he and his men had succeeded in crossing the continent from sea to sea, the story would probably be forgotten today.

It is the fact that the journey turned into a series of disasters and escapes that makes it so compelling.

In some ways it is the most remarkable tale of survival in modern history.

There is also a wealth of historical detail to draw on, and some great characters.

I think the story is great to write about because it is like something from science fiction, with the humans marooned on a distant planet, without communication, and cut off from planet Earth.

You could try writing your own story about characters who are lost and who have to find their way back home.

What’s happened to them?

Where do they go?

How do they get home?

Who is your favourite character in this opera?

I like Harry McNish (also known as McNeish), one of the oldest in the crew, the ship's carpenter, and the owner of Mrs Chippy the cat.

He was in no way a hero, and he didn't get on that well with

Shackleton.

But it was McNish who made the little dinghies seaworthy, and he prepared the

James Caird lifeboat for the final journey.

He was one of the few men Shackleton trusted enough to take with him on this last and scariest leg of the voyage.

If there was a leak Harry would fix it.

It

seems cruel and unjust that he was not awarded the Polar Medal.

How is an opera written?

What do you start with?

How long does it take?

.

You have to begin with a really good idea.

It might be an idea that seems impossible to achieve, but you need something that is strong and thrilling.

Then the librettist (writer), the composer and the designer have to agree that the idea itself is a strong one.

The next stage is for the librettist to map out the structure of the story.

In this case it was hard because we needed to cram a story lasting 2 years into an opera lasting 60 minutes.

Then the librettist has to write the words of the opera, bearing in mind that the words will be sung.

Generally there are about 5 drafts of the libretto or script, and each draft is sent to the composer to look at.

Finally the composer starts to write the music.

Depending on the number of instruments in the orchestra or ensemble the composition of the music can take a very long time.

Meanwhile the production of the opera (the work of the director and designer) starts to develop.

In all it takes about 6 months to write an opera.

14

Designs for the set of Shacketon’s Cat , by Jude Munden

Before composing the music for Shackleton's Cat I imagined how

Antarctica would have looked and felt for Shackleton and his men. I pictured the terrifying seas, the endless sheets of ice, and I thought about the howling wind and bitter cold. I then tried to create these images in the music I composed so that the audience feel like they are in the Antarctic.

You can try this too. Find a picture of Antarctica and compose a piece of music to describe what you see. Which instruments will be most effective and how should they be played? Can you create contrast in the music as it goes along - perhaps adding different instruments?

Don't forget you can always use your voices as well - you could even make up some words to sing as part of your piece. Can you help the listener imagine the picture you have been looking at?

Russell Hepplewhite, composer

Photos: Rebecca Moffatt

Classroom

activity

ideas

Are

we

nearly

there

yet?

Fact

The planned route for the expedition was: Weddell Sea to South Pole, South Pole to Ross

Island.

Tasks

Curriculum links

Draw the planned route on a map: What do you think the main potential problems could be?

Draw the actual route on a world map: London, Chile, South Georgia, Weddell Sea,

Elephant Island, South Georgia.

Compare the two.

Geography: location and place

Maths: measurement, addition and subtraction

16

How

do

I

get

there?

Fact

Task

Shackleton, Worsley and Crean were the first men to cross the mountains of South Georgia.

Afterwards they recorded their route.

Think about a journey you have made.

Draw a map to explain to others how you got there.

It can be a journey you made to go on holiday, your route from home to school, or even from your classroom to somewhere else in the school.

Geography: mapping, location, place

Curriculum links

The

map

of

me

Fact

Tasks

Curriculum links

Many geographical features on Antarctica were named after the explorers who went there

– not just from Shackleton’s expedition, but also from Scott’s and Amundsen’s, explorers

who also visited the region.

Look at a map of Antarctica and find the places named after explorers.

Can you think of any other places named after people?

Looking at a map of your local area, can you find any

streets or places named after people?

Draw a map of your local area, an area you know well, or an island of your imagination.

Rename or name geographical features after people who are important to you.

Why have

you named each place as you have?

Art: making art

Geography: reading and creating maps

Sing

‐

a

‐

long

‐

a

‐

sea

‐

shanty

Fact

Tasks

Curriculum links

“Some of us had presents from home to open.

Later there was a really splendid dinner…Christmas pudding, mince ‐ pies, dates, figs, and crystallized fruits...In

the evening everybody joined in sing ‐ song.

Hussey had made a one ‐ stringed violin.” – quote from

Shackleton’s account of the voyage.

Sailors frequently made up their own words to be sung with well known tunes.

Write your own sea shanty using this method.

Write it out with the tune.

Have a class sing ‐ along.

Make a musical instrument using an everyday object then use it to accompany a song.

Music: composition, understanding how music is put together, singing, playing an instrument

Science: sound

Design Technology: design and make an instrument using an everyday object

17

18

Icy

Sounds

Fact

Task

Shackleton describes the sound of the ice as it freezes around the ship and begins to crush the wooden frame.

“We heard tapping as from a hammer, grunts, groans and squeaks, and electric trams running, birds singing, kettles boiling noisily, and the occasional swish… I could hear the

creaking and groaning of her timbers.”

Compose your own piece of music to describe the crushing of Shackleton’s ship, the

Endurance .

You can use instruments you have made, objects around the room, your voices, or any instruments the school might have.

What does the world sound like in your everyday life?

Can you create a musical

composition based on this?

Music: composition

Curriculum links

Snappy

Snaps

Fact

Task

Frank Hurley, from Australia, was the expedition photographer.

He photographed daily life.

Hurley was always ready with his camera, even in the toughest conditions.

Without Hurley’s photos, this story wouldn’t have been believed.

In those days photos were developed on heavy glass plates.

Hurley realised that he couldn’t

take all his wonderful photos with him as they were too heavy to carry.

He picked out the best ones and smashed the others – it was the only way he could leave them.

Record everyday life with a series of photographs.

Edit your photos; if you could only keep three, which would be the best ones to save?

Art: recording experiences, becoming proficient in art techniques

Curriculum links

Flat

Pack

Conundrum

Fact

Tasks

Curriculum links

Shackleton had taken a large wooden hut to Antarctica in pieces to put together there – like flat pack furniture.

This is where some of the men would spend the winter.

Time was

beginning to run out and soon the winter would be upon them.

As a group, follow some instructions to build something flat packed, or from lego.

How easy were the instructions to follow?

Write some instructions for a friend to follow.

English: Spoken word, instructional text

Design and Technology: evaluation of product

Volunteers

Please!

Fact

When Shackleton was looking for men to go on the expedition he put an advert in a newspaper in 1912 (this picture is a reproduction):

Tasks

Curriculum links

Would you have wanted to go on the expedition, based on this advert?

Thousands of men and several women came forward and they must have been amazing people to be willing to face such a challenge.

The final crew of 28 included men that had been on Captain Scott’s

last expedition a few years before.

There were scientists, doctors, engineers, and of course sailors.

Advert : you need people to go on an expedition, decide what sort of people you are looking for then write and illustrate an advert to recruit people.

Respond , by letter to somebody else’s advert, or to Shackleton’s.

Why should you be taken on the expedition?

See an example of a real letter on the next page.

Sift: read someone else’s letter, would you interview this person?

Interview: write questions, then interview candidates for the expedition.

English: Vocabulary, handwriting, spoken word, persuasive text, advertising, letter writing, questioning, use of formal language

19

20

Extract from letter to Shackleton, photo courtesy of Scott Polar Research Institute, University of

Cambridge.

Full transcript reads:

Dear Sir Ernest,

We “three sporty girls” have decided to write and beg of you to take us with you on your expedition to the

South Pole. We are three strong, healthy girls, and also gay and bright, and willing to undergo any hardships that you yourselves undergo.

If our feminine garb is inconvenient, we should just love to don masculine attire. We have been reading all books and articles that have been written on dangerous expeditions by brave men to the Polar regions, and we do not see why men should have all the glory, and women none, especially when there are women just as brave and capable as there are men.

Trusting you will think over our suggestion, we are Peggy Pegrine, Valerie Davey, Betty Webster.

P.S. We have not given any further particulars, in case you should not have time to read this, but if you are at all interested, we will write and tell you more about our greatest wish.

Honour

Fact

Task

Curriculum links

After the men returned from the expedition, most of them were awarded the Polar Medal – but not Harry McNish.

It is said that this might have been because of Shackleton’s personal dislike for him, even though no one could deny his skills in shipbuilding.

He was never seen to take measurements, producing perfect work by eye.

“I was disheartened to learn that McNish… had been denied the Polar Medal...of

all the men in the

party no ‐ one more deserved recognition than the old carpenter....I

would regard the withholding of the Polar Medal from McNish as a grave injustice.” – Alexander Macklin, one of the other men in the crew

Do you think it is right that McNish did not receive a medal?

Why/why not?

Write a letter to the Queen to explain your opinions, either to persuade her to award

McNish the medal posthumously (after death), or in

support that he did not receive it.

English: Vocabulary, handwriting, spoken word, persuasive text, letter writing, use of formal language

Regret

Fact

Task

Curriculum links

10 months earlier, Shackleton had missed the chance of sheltering the Endurance in Glacier

Bay safely away from the sea ice.

He knew this was a mistake, and later regretted it.

Discussion: What have you regretted?

Why?

What would you have changed?

English: spoken word

Emergency!

Fact

Task

Curriculum links

Shackleton had been preparing for this disaster through the winter, as it became clear that the ship would be destroyed.

The crew had taken everything needed to camp on the ice

floes off the ship before she was crushed.

What would you take off the ship?

Why?

If you had to put together a survival kit from the things in your home, what would you take and why?

Make a poster of your survival kit, with drawings or a collage, and explanations for each item.

Art, Design: Making and evaluating

English: justifying decisions, critical thinking

21

22

Dear

Diary

Fact

Lots of Shackleton’s men wrote diaries.

Tasks

Curriculum links

Shackleton’s diary, photo courtesy of Scott Polar Research Institute

Keep a diary to record your life over the next week.

Imagine that you are one of Shackleton’s men, record what’s happening and how you feel

English: recount, diary writing, composition, handwriting

Waterproof

Fact McNish, the carpenter, spent the days before leaving making the James Caird lifeboat more seaworthy.

He made a cover for the boat from canvas sail material so that she wouldn’t fill

up with water in the stormy seas.

Tasks

Curriculum links

Experiment: use everyday objects to test for waterproofness: plastic bags, fat, different fabrics, etc.

Record and share your results.

What is the most waterproof material?

Experiment: using a takeaway container punched with holes, can you keep it floating on

water by waterproofing it?

(Clue: in 1915, McNish used seal blubber and oil paint)

Science: properties and changes of materials, working scientifically, uses of everyday objects

Morale

Boosting

Fact

Tasks

Curriculum links

Shackleton understood the importance of good morale (feeling contented, happy and cheerful).

He allowed each man to keep about 2 pounds in weight (about 1kg) of their own

belongings, rather than just keeping essential items.

Discussion: what cheers you up?

Why?

Plan : make up a bag of personal belongings that cheer you up, weigh it to make sure that it

is less than 1kg.

Maths: measurement, addition, subtraction

English: spoken word, discussion

Brrrr,

I’m

cold!

Fact

Tasks

Curriculum links

Antarctica is the coldest and windiest place on the planet.

Explorers frequently tested out new clothing to keep them warm, including string vests!

They also adapted the clothing

they had to maximise the retention of heat, to stop them from getting cold.

Experiment: test different pieces of clothing to find out which is warmest, e.g.

mittens or gloves

Experiment: test multiple thin layers, thick layer, different types of fabric etc.

Task: how would you adapt your school uniform to make it as warm as possible?

Describe

and draw your Antarctic school uniform.

Science: properties and changes of materials, working scientifically, animals including humans, uses of everyday objects

Portrait of Sir Ernest Shackleton (photo courtesy of Scott

Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge).

Look at what he is wearing and discuss how his clothing has been designed to keep him warm.

23

24

Goal!

Fact

Tasks

Curriculum links

The men played hockey and football on the ice floes and in the evenings they had rowdy concerts.

Endurance was like an island of cheerfulness in strange contrast with the cold,

silent world that lay outside.

Plan some group games so that everybody takes part.

The aim is to have fun, keep warm and keep morale high.

Did you have to change the way you played the game in order to keep everybody happy?

Why would this have been important?

Physical Education: keeping fit, teamwork

Penguin

power

Fact

Tasks

Curriculum links

Male Emperor penguins protect their egg by balancing it on their feet.

The penguins have to keep moving in order to keep

themselves, and the egg, warm.

Invent a game: using bean bags as eggs, balance the egg on your feet, keep moving and don’t let the egg fall off.

Now work as a team and turn this activity into a game with rules.

Physical Education: team work, keeping fit, balancing, game rules

English: instructional text

P

is

for…

Fact

Tasks

Curriculum links

Shackleton’s men saved the Encyclopaedia Britannica from the Endurance before it sank.

They used to read it, test their general knowledge and also tear out pages to use as toilet

paper!

We mostly use items for one purpose, but in a survival situation, a small number of items would have to be used for many things.

Choose an everyday object (brick, pencil, paperclip, bucket), list as many different ways to use it as you can think of.

Who can think of the most uses?

Design Technology: planning, design, lateral thinking

Come dine with me on ice

Fact Shackleton knew that sooner or later the ice would melt and they would have to make a boat journey. This is when they would eat the sledging rations that were going to be used when crossing Antarctica. Meanwhile they would eat hooch - a stew made from a mixture of dried meat, fat and cereal, together with ground biscuit and any fresh meat that could be found, along with water (from melted snow). This was the standard fare of the Shackleton expedition when they lived on the ice. Later on their food was even more basic and consisted of penguin and sometimes seal meat. The men would eat almost every part of the animals they killed, wasting nothing, and using the rest as fuel.

One man wrote: “The dried vegetables…all go into the same pot as the meat, and every dish is a sort of hash or stew, be it ham or seal-meat or half and half…The milk-powder and sugar…boiled with the tea or cocoa.”

Task

Curriculum links

Food provisions on the Endurance

Photo Talia Lash, taken at the Polar Museum at Scott Polar Research Institute

In a small group, with adult supervision, use a primus or camping stove to heat water and make a hot drink or soup.

Using a selection of foods, decide what you could take to the Antarctic and what couldn’t be taken (you could experiment by freezing different foods).

Plan a polar meal.

Design Technology: cooking

Science: plants, living things, temperature, states

That’s my motto

Fact

Tasks

Shackleton named his ship Endurance after his family motto ‘Fortitudine Vincimus’, which is

Latin for ‘by endurance we conquer’. A motto is a short phrase that sums up the aims or beliefs of a group or individual.

Discussion: What would your family motto be? Does your school have a motto? What would be the motto of your class? In groups, decide on the best motto for your class, and write the reasons why you have chosen this.

Present your motto and reasons to the class. You could have a vote to decide on the class’s new motto.

Draw a poster or coat of arms to illustrate your motto

English: Vocabulary, handwriting, spoken word, persuasive text Curriculum links

25

26

Artists

Creative Team

Russell Hepplewhite – Composer

Russell studied at Chetham’s School of Music in Manchester and subsequently at the Royal College of Music, where he was awarded a scholarship to study piano with Head of Keyboards Andrew Ball and composition with Timothy Salter.

Russell's music has been performed by distinguished musicians at major venues including the Wigmore Hall, the Library Theatre

Luton, the Purcell Room and the Queen Elizabeth Hall. Russell has also had musicals developed at the National Theatre Studio and performed in the Sheffield Crucible

Theatre. Recent performances have included a number of UK and overseas performances and premieres of Russell's work, with venues including Glyndebourne, Snape Maltings and Kings Place

London. Laika the Spacedog, commissioned by English Touring Opera, was awarded the David

Bedford Award and was featured on the BBC before receiving its premiere at London’s Science

Museum in 2013 and embarking on a nationwide tour of the UK. It was also performed at the

Armel Opera Festival in Hungary and in Avignon, France.

In addition to his composition and performing schedule as a pianist, Russell is an examiner for the

Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music and teaches Musicianship and Composition at the

Royal College of Music Junior Department.

Tim Yealland – Writer, Director and Head of Education at English Touring Opera

Tim read English at Cambridge University, and then studied singing at the Guildhall School of Music in London, and at the Hochschule für Musik in Munich. As a singer and actor he performed roles for

English Touring Opera (including the title role in Don Giovanni),

Opera Factory, Opera 80, Opera North, English National Opera and the Chichester Festival.

For many years he has been active as a director working particularly in the community. He has created projects for all the leading opera companies and many orchestras, including the Royal

Opera House, Glyndebourne, English National Opera, Opera North, and the London Symphony Orchestra. Tim also directs ETO’s outreach programme. He directed

Fantastic Mr Fox for ETO in 2011, and also created a book called Foxtales . Large community projects with ETO have included One Breath in Sheffield, A House on the Moon in Wolverhampton, and the award-winning One Day Two Dawns in Cornwall. He works regularly at the Casa da Música in Portugal, most recently devising Spirit Level , a large-scale piece with actors, dancers and musicians. As a writer he has created the words for and directed many operas for young people and families including recently In the Belly of the Horse , Voithia, The Feathered Ogre, Laika the

Spacedog, Borka and Spin. Last year he helped create two new community operas: Zeppelin

Dreams in Wolverhampton and Curado in Porto. Apart from Shackleton's Cat he is currently working on a new opera called Waxwings for young people with special needs.

Jude Munden – Designer

A Fine Art graduate from Falmouth College of Art, Jude was a teacher before becoming a full time maker/designer. She makes costumes, props, puppets, scenic art and models for film, theatre and exhibition, working from a barge on the Penryn River that she shares with her set builder husband, Alan.

She has been working with ETO since One Day Two Dawns in 2009 on projects including Under the Hill , Severn Stories, In the Belly of the Horse ,

Spirit Level , The Fox and the Moon, La Clemenza di Tito, Laika the

Spacedog and Borka . Jude also works with Miracle Theatre in Cornwall and is a founder member of Pipeline Theatre.

Jude has three children and lives in Falmouth, Cornwall.

Cast

Matt Ward – McNish

This year for English Touring Opera Matt will perform Giacomo L’Assedio di Calais . Last year for ETO Western Union Boy in the Olivier Award

Winning production of Paul Bunyan , Cpt McAllister Borka, Young Guard

(cover) King Priam and Monostatos (cover) Magic Flute. Matt studied at the Royal College of Music supported by the RCM Yvonne Wells Award.

Roles at RCM: Arnalta in L’Incoronazione di Poppea , Frick in La Vie

Parisienne and Don Curzio in Le Nozze di Figaro . For the West Australian

Opera Company Matt performed Mercury Orpheus in the Underworld and The Rector (cover) Peter Grimes.

Andrew Glover – McNish

New Zealander Andrew Glover made his operatic début with New Zealand

Opera, where he performed Beppe I Pagliacci and Vasek The Bartered Bride, and Sellem The Rake’s Progress with the Auckland Philharmonia Orchestra.

He has sung a number of roles with English Touring Opera - Monsieur Triquet

Eugene Onegin, Gherardo Gianni Schicchi , Giovanni L’Assedio di Calais , and

Tinca Il tabarro . He has also performed Lysander A Midsummer Night’s

Dream for Opera North, and Remendado Carmen , Don Curzio/Don Basilio The

Marriage of Figaro and Beppe I pagliacci for Opera Holland Park.

He has sung concerts with the Tokyo Philharmonic Orchestra, New Zealand Symphony

Orchestra, Auckland Chamber Orchestra, Christchurch Symphony Orchestra and the Perth Orchestra.

Dominic Walsh – Wild

Dominic’s professional debut at the age of 26 was as Ferrando in Così fan Tutte for Opera Queensland in 2011. The following year, he played Nanki-poo in The

Mikado . He is a Guildhall Artist Masters Graduate from the Guildhall School of

Music and Drama and completed a BMus(Perf) at the Queensland

Conservatorium.

Dominic’s awards include the Chairman’s Prize and the Concert Recital

Diploma from the Guildhall School and scholarships from the Guildhall School

Trust, the Ian Potter Cultural Trust, the Australia Council, and the Australia

Music Foundation’s Guy Parsons Award. In 2014, Dominic covered the

Schoolmaster in Cunning Little Vixen for Garsington Opera.

27

28

Michael Butchard – Wild

Michael grew up in the Blue Mountains west of Sydney, Australia.

Born into a musical family, he learned piano, saxophone and oboe, but his favourite thing was singing. He studied at the University of Sydney, and the

Sydney Conservatorium of Music, and in 2011 he moved to London, with his wife Bonnie, to study at the Royal College of Music. Since then, he has sung with many choirs and opera companies in the UK and hopes to work in Germany in the future. Besides his passion for opera, in his free time Michael bakes bread, brews beer, roasts coffee and loves to potter in his veggie garden.

Jan Capinski – Worsley

Jan was born in Kraków, Poland, where he studied before moving to the UK in

2009. He trained at the Royal Welsh College of Music & Drama and ENO Opera

Works, and has sung roles with Mid Wales Opera, Garsington Opera, Scottish

Opera, British Youth Opera, and several smaller companies. Outside singing he is a keen blogger, stand-up-paddleboarder, as well as a freelance recording engineer. To find out more about Jan, feel free to visit www.capinski.com

Jamie Rock – Worsley

Irish baritone Jamie is equally at home in opera, concert and recital repertoire. In 2015, Jamie is making his debut with ETO, performing in the chorus of all three evening operas and Shackleton’s Cat as well as covering principal roles in La Bohème and L'Assedio di Calais . Recent performances include Masetto in Don Giovanni for Regent’s Opera and covering Filip Burgrave in Dvorak’s Jacobin for Buxton Festival Opera. In concert, Jamie has performed the Requiems of Mozart, Brahms, Duruflé and Fauré; Haydn’s Creation and Handel’s Messiah at venues such as the

Usher Hall (Edinburgh), National Concert Hall (Dublin), and Salzburg

Cathedral. He’s also a member of the vocal ensemble Quartet , who explore a wide range of music and look for new ways of presenting the vocal repertoire.

Gareth Brynmor John – Shackleton

Winner of the 2013 Kathleen Ferrier Award, baritone Gareth held a choral scholarship at St John’s College, Cambridge, before studying at the Royal Academy of Music. He won the RAM Patrons' Award and was awarded the WCoM Silver Medal and an Independent Opera

Postgraduate Voice Fellowship. His operatic roles include Eugene

Onegin and Claudio (with Sir Colin Davis), and he recently understudied several roles for WNO. Recent recitals have included King's Place, King's Lynn

Festival, and Leeds Lieder. He performs in the London English Song Festival, recently giving a programme of Great War composers at St George's Hanover Square. He recorded Mahler Lieder eines fahrenden gesellen with Trevor Pinnock and the RAM Soloists Ensemble for release with Linn

Records.

Ashley Mercer – Shackleton

Born and raised in Essex, Ashley's interest in singing began at school where he was a member of the school choir, and later as a member of the National Youth

Choir. At university he performed in, directed and conducted a number of musicals and operettas, and afterwards continued performing with amateur groups in London. He recently decided to study singing more formally and last year completed a Masters at the Trinity Laban Conservatoire where he was a

TCM Trust Scholar and a Kathleen Roberts Scholar, and was awarded the Paul

Simm opera prize. Recent work includes Silent Night (European premiere) for

Wexford Festival Opera, and Il barbiere di Siviglia for Opera Holland Park, where he was a Christine Collins Young Artist.

Dafydd Hall Williams – Staff Director, Blackborow

Dafydd is from a small town in North Wales called Llangollen. Since finishing his training at Aberystwyth University, Dafydd has worked as an assistant director for companies like Buxton Opera Festival, Mid Wales Opera, The

Royal Academy of Music, Wexford Festival Opera and English Touring Opera.

One of the most fun things Dafydd has ever done was play the part of Archie the Goose in the ETO Spring 2014 tour of Borka, the Goose with no Feathers .

After this tour, Dafydd will be directing a set of Opera Scenes at Guildhall

School of Music and Drama.

Kate Jones – Stage Manager

Kate recently graduated from the Liverpool Institute for Performing Arts, where she studied Theatre and Performance Technology. Her love of opera stems from a placement with Norwegian company Opera Ostfold, and a background in musical theatre. Her past opera credits include

Lighting Designer for For Lenge, Lenge, Lenge Siden, performed at the

Festival of Music for Winds and Percussion in Fredrikstad, Assistant Stage

Manager for Liverpool Philharmonic’s Tosca and Assistant Production

Manager for Opera Ostfold’s production of Nabucco. This summer she will return to Opera Ostfold for their production of Tosca.

Players

James Henshaw – Conductor, Keyboard

James Henshaw is a promising young conductor. He studied Music at Clare College, Cambridge where he was a choral scholar and award-winner as both conductor and pianist. Having graduated with a Distinction in Repetiteuring from the Guildhall School of

Music and Drama, he recently assisted on Owen Wingrave at the

Photo: Clare Park

Aldeburgh Music Festival and then at the Edinburgh Festival as well as recently working at the Proms with the BBC National Orchestra of Wales.

Recent concerts have included Brahms and Mozart Requiems and performances ranging from John Adams to Mozart. Over the coming year he will continue to work with his orchestra based in Notting Hill and Ashtead

Choral Society.

29

30

Jonathan Hassan – French Horn

Jonathan was born in Reading a long time ago. He started the horn aged ten and, after studying at The Royal College of Music, has worked as a freelance player and teacher, a brilliant job that has taken him all over the world, from

South America to Europe and Asia. He has also played in many West End shows including Shrek and West Side Story .

With his teaching hat on he loves helping children achieve their musical potential on the horn and trumpet. He also regularly visits schools to perform

Jurassic to Jazz , an interactive show tracing the history of brass instruments.

Jonathan Raper – Percussion

Having developed a passion for all things percussion at school, Jonny went on to study music at Trinity College of Music in London. He has played in a wide variety of musical genres from rock to baroque, and has been required to play all manner of instruments from tubular bells to coconut shells. Jonny is passionate about bringing classical music into schools, and hopes that it will enrich the lives of young learners as it has done his own. He has performed in school education projects for such institutions as the English National Ballet, Philharmonia

Orchestra and O Duo as well as having been with English Touring Opera for a number of years.

As well as some of the instruments above, you will also see and hear a theremin being played in the show. The theremin is an electronic instrument invented by Leon Theremin in 1928. It is played by moving your hands in the space near the metal rod. One hand controls pitch and the other controls volume. It is one of the only instruments you play without touching it! The theremin’s eerie sound has made it popular in science fiction soundtracks, though it is also heard in other types of music, especially in psychedelic rock. You will also hear our specially made wind machine!

Song words

Please learn these songs in advance of our performance and join in during the show.

The singers might not prompt the children, so please join in as soon as you recognise the music!

The tracks are all on the CD sent with the pack, or on ETO’s website.

Children should learn the melody sung by the

female voice, not the male voice.

Larsen’s

Standing south

Leaning

As

we

Waiting white

Trying

What

Boat on on

make

to and not will

the the

(Standing for

rails meet blue.

to

deck the the think happen

of sea.

on pack about when

a

boat made we

the do.

Larsen’s

boat,

last

of

its

kind.

deck) heading of

ice

that’s

Paulet

Forty then

‐

Isle six

three

(46 miles hundred

Let’s

travel

in

style

To

Paulet

Isle!

Miles) takes

only more

a

to

while

Paulet

Isle x

3

Looking

Waiting

for for

the the

land sight

beyond

the

sea

Of

the you’ll

Trying

What

Praying

far

Larsen’s

be

not will

polar you

dead.

to

boat,

shore.

don’t think happen last

fall

in of

in, about the its

in

two end.

kind.

minutes

Stuck

Fast

Stuck

fast,

stuck

in

the

ice

Stuck

in

Icebergs

the

and sea,

we’ll

never humpbacks,

get

finners free

and of

the

blues, ice.

The

killer

whales,

kings

and

long

tailed

gentoos.

Stuck

fast,

stuck

in

the

ice

Stuck

in

the

sea,

we’ll

never

get

free

of

the

ice.

Stuck

fast,

stuck

in

the

ice

Stuck

in

the

sea,

we’ll

never

get

free

of

the

ice.

Crabeaters,

furs

and

elephant

seals,

the

emperors,

chinstraps

and

adelies.

31

Lyrics by

Tim Yealland

Larsen's Boat

Piano

q

= 100

Heroic

mf

Music by

Russell Hepplewhite

Pno.

3

ff

3

3

Children

6

Pno.

ff

Stand

ing

on the deck of a boat

3

south

Children

Pno.

8

on

the rails

as we

3

f

Children

11

Pno.

3

make for the sea

Wait ing

to meet the pack made of ice that's

Children

13

and blue.

Pno.

not to think a bout

Children

Pno.

15

What will ha ppen when we do

Lar sen's boat

last of its kind..

Pno.

17

f

cresc.

ff

Pno.

20

3

Children

22

Pno.

ff

for

the land

be yond

the Sea

Children

24

Pno.

Wait ing for f

3

mf

the sight

Children

26

of

Pno.

the far

3

Po lar shore

Children

28

you don't

3

fall in, in two min utes

Pno.

you'll

be dead

Children

Pno.

30

Try ing not

to think a bout

What will ha

ppen in the end.

Children

Pno.

32

boat

last of

its kind.

f

Lyrics by

Tim Yealland

Piano

Stuck Fast

Music by

Russell Hepplewhite

McNISH (not children)

3

Fif -

ty

days at sea

and now we're stuck.

mf

Pno.

3

f

like an

al mond

in a

cho colate bar.

5

q

= 110

Forceful

Pno.

f

+ CHILDREN

Stuck

fast

stuck in the ice

3

Pno.

8

3

Stuck in the sea

3 we'll nev

3

er get free

3

of the

ice

14

Pno.

Pno.

10

Ice bergs

3

3

and hump

backs

finn ers

3

and blues,

3

the

12

kill

Pno.

-

3 er

whales,

kings

3

and

long

-

3 tailed

gen -

toos.

Pno.

13

Gap here as scene continues here.

Stuck

fast

3

stuck in the ice

Pno.

17

3

Stuck in the sea

3 we'll nev

-

3

er get free

3

of the

ice

Pno.

19

Gap here as scene continues here.

20

Pno.

Stuck

fast

3

stuck in the ice

Pno.

23

Stuck

3 in

the

sea

3 we'll nev

3

er get

free

3

of the

24

ice

Pno.

3

ers, furs

3

3

and el e phant seals,

3

the

27

em

3

pe

-

Pno.

rors,

3

and chin

straps

ad

3

e

-

lies.

Lyrics by

Tim Yealland

Piano

Paulet Isle

Full of macho power. f

Music by

Russell Hepplewhite

Children

5

For ty six

miles

Pno.

takes

on ly a while

then three

more

to

Children

8

Pau -

let Isle.

Pno.

Let's tra vel

in style

4:3

4:3

4:3

4:3

4:3

4:3

Children

Pno.

12

to Pau

4:3

-

let Isle.

Children

17

Pno.

f

For ty six miles

takes

Children

20

Pno.

Pau

-

let Isle.

on

-

Let's tra vel ly

4:3 a while

in style

then

three

4:3

4:3

more

to

4:3

Children

23

Pno.

4:3

4:3

Children

27

to Pau

let Isle.

4:3

4:3

f

Pno.

For ty six f

4:3

miles

takes

4:3

Children

30

on ly a while

then three more

to Pau -

let Isle.

Let's

Pno.

4:3

4:3

4:3

4:3

4:3

4:3

Children

33

tra vel in style

Pno.

4:3

4:3

4:3

4:3

4:3

4:3

Children

36

Pno.

to Pau rit.

let Isle.

mp

Further information

Links

Scott Polar Research Institute photo archive to see pictures from the voyage: http://www.spri.cam.ac.uk/library/pictures/catalogue/itae1914 ‐

16/gallery/

Facts, interactive games, activities, clips:

http://www.discoveringantarctica.org.uk/

Stop ‐ motion animation made by children in Ireland about Tom Crean: http://vimeo.com/45032707

Snowlab, where you can contribute to national statistics about snow:

http://www.spri.cam.ac.uk/research/projects/snowlab/

Wordpress blog “Shackleton In Schools” activities created by a teacher: https://emmalkerr.wordpress.com/

Skip ‐ count maths worksheets with polar animals: http://www.atozkidsstuff.com/images/penguins/skipcountpenguin2.pdf

http://www.atozkidsstuff.com/images/penguins/skipcountpenguin5.pdf

Books to read

Mrs Chippy's Last Expedition: The Remarkable Journal of Shackleton's

Polar ‐ Bound Cat by Caroline Alexander

Ice Trap!

Shackleton’s Incredible Expedition by Meredith Hooper & MP

Robertson

Places to visit

You can see the navigational equipment used on the voyage of the James Caird, some of

Shackleton’s belongings and a replica of the lifeboat at:

You can see the James Caird lifeboat at:

Dulwich College

Dulwich Common

Polar Museum

Scott Polar Research Institute

Lensfield Road

Cambridge

CB2 1ER

01223 336540

www.spri.cam.ac.uk

Discovery Point

Discovery Quay

Dundee, DD1 4XA

01382 309060

www.rrsdiscovery.com

London

SE21 7LD

020 8693 3601 www.dulwich.org.uk

You can see some artefacts from Shackleton’s

voyage at:

National Maritime Museum

Park Row

London

SE10 9NF www.rmg.co.uk

43

©

3 rd

floor, 63 Charterhouse Street, London, EC1M 6HJ

020 7833 2555 www.englishtouringopera.org.uk