working paper PDF - Institute for Policy Research

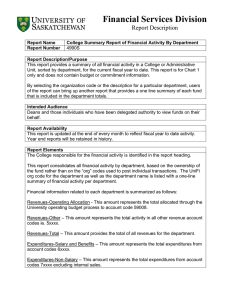

advertisement