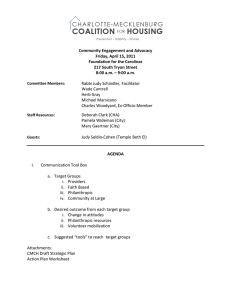

New York, New York Text

advertisement