PDF Edition - Review of Optometry

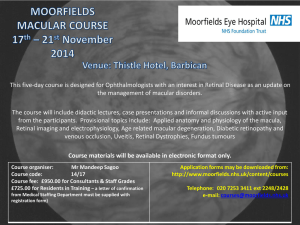

advertisement