Appendix 1: Overcrowding and Health

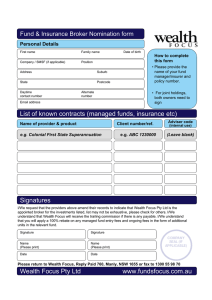

advertisement