Hurricanes and mangrove regeneration

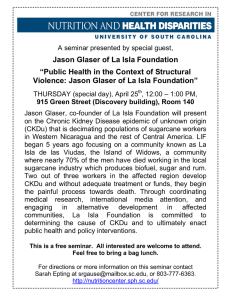

advertisement

Hurricanes and Mangrove Regeneration: Effects of Hurricane Joan, October 1988, on the Vegetation of Isla del Venado, Bluefields, Nicaragua Author(s): Linda C. Roth Reviewed work(s): Source: Biotropica, Vol. 24, No. 3 (Sep., 1992), pp. 375-384 Published by: The Association for Tropical Biology and Conservation Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2388607 . Accessed: 22/10/2012 12:38 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org. . The Association for Tropical Biology and Conservation is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Biotropica. http://www.jstor.org BIOTROPICA 24(3): 375-384 1992 Hurricanes and Mangrove Regeneration: Effectsof HurricaneJoan, October 1988, on the Vegetation of Isla del Venado, Bluefields, Nicaragua1 Linda C. Roth Graduate School of Geography,Clark University, Worcester,Massachusetts 01610, U.S.A. ABSTRACT Based on samplingof a hurricane-damaged Caribbeanmangroveforest,stand structure and compositionare charwas typicalof mangroveforests acterizedforbothpre-and posthurricane vegetation.Beforethestorm,standstructure throughoutthe region,but poorlydevelopedcomparedto upland forestsin the same lifezone, as expressedin a compositeindexof treeheight,basal area,stemdensity,and speciesdiversity. The hurricaneinflicted the mostsevere damage upon the largesttreesand markedlyreducedthe complexityindex of the stand,but it appears to have favoredthe establishment of abundantregeneration by all of the originalmangrovespecies.Periodicdestruction of Caribbeanmangroveforests by cyclonicstormsis proposedas one explanationfortheircharacteristically low structural complexityas well as the lack of typical"climax" componentsin the vegetation. RESUMEN En base al muestreode un manglarcaribeiioafectadopor vientoshuracanados,se caracterizanla estructuray la del rodalantesy despuesdel cicl6n.Antesdel huracan,esterodalpresentabaun desarrollo composici6nvegetacionales estructural tipico de los manglarescaribenios pero pobre en comparaci6ncon bosques de tierrafirmedentrode la mismazona de vida, segunun indicebasado en la altura,area basal, densidady diversidadde los arboles.El huracan provoc6los daniosmas severosentrelos arbolesmas desarrolladosy redujomarcadamenteel indicede complejidad del rodal,peroparecehaberpromovidoel establecimiento de regeneraci6n abundantede todas las especiesde mangle previamentepresentes.La destrucci6n peri6dicade los manglarescaribenospor tormentas cicl6nicasse proponecomo una explicaci6nde su complejidadestructural caracteristicamente baja asi como la faltade un tipico componente "climax" en esta vegetaci6n. Keywords: diversity; foreststructure; hurricanedamage;mangrove; succession. Nicaragua; regeneration; DISTRIBUTION ALONG LOW LATITUDE SEACOASTS 1959, Craighead & Gilbert 1962, Sauer 1962, inevitably placesmangroveswampsamongtheter- Stoddart1963, Vermeer1963, Glynnet al. 1964, restrialecosystemsmost prone to experiencethe Alexander1967, Heinsohn& Spain 1974, Bunce passage of hurricanesand othertropicalcyclones. & McLean 1990, Wunderleet ail. 1992), but the Because the frequency of such stormsat any one accountsare, forthe mostpart,generaland qualsiteis commonlywell withinthepotentiallifetime itative.Virtually completedefoliation bywindand/ of individualtrees(Egler 1952, Stoddart 1963, or waves,shearingof branchesand trunks,uprootGentry1974, Lugo et ail. 1976, Neumann et ail. ing of some trees,damage to bark,and the depopre- sitionof sedimentand organicdebrisoftenproduce 1981, Boucher,in press),thesedisturbances theselectionregimesofmangrove an initialimpressionof completedevastation.Redictablyinfluence speciesas well as theircommunitydynamics.An cuperationof some of the strippedtreesmay take understanding of mangroveresponsesto hurricane place throughsproutingand refoliation (Craighead impactshouldassistin interpreting thedistribution & Gilbert 1962, Sauer 1962); failureto recover and structure of theseecosystems and in designing depends in part on speciescharacteristics (Wadsappropriatemanagementstrategies. worth & Englerth1959), topographicsituation Numerous reportsof the ecologicaleffectsof (Craighead & Gilbert 1962), sedimentationand hurricanes mentiondamageto mangrovevegetation drainagepatterns(Craighead 1971, Heinsohn & (Davis 1940, Egler 1952, Wadsworth& Englerth Spain 1974, Cintr6net ail. 1978), and proximity to the hurricanetrack(Stoddart1963). Seedlings I Received 1 March 1991, revisionaccepted25 Novemand saplingsoftensurvivethestormor appearprober 1991. lifically in subsequentmonths(Craighead& Gilbert THEIR 375 376 Roth LA af~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ 3 2 < Lf X~~~~~~~~~~DE BLU E FI E LDSf L~ ~ ~ ~~~~~~~~/ IL FIGURE 1. Compositemap locatingIsla del Venado ( 11?55'N; 83045'W) in relationto Bluefields,Nicaragua, and indicatingmangrovecommunities(hatchedarea) and numberedsamplingtransects(0). 1962, Sauer 1962, Craighead 1964, Alexander occur 1967, Wunderleetal. 1992), but exceptions (Egler 1952, Stoddart1963). Long-termstudies appear to be tracingthe fateof this regeneration ofmangrove nonexistent, and althoughtherecovery iswidelyrecognized (Lugo ecosystems after hurricanes & Snedaker1974, Jim6nezetal. 1985), theprocess is poorlydocumented. The presentsurveywas undertaken17 months acrossan aftera Caribbeanhurricane sweptdirectly extensivestand of mangroveforest.Objectivesof thesurveywereto recorddamageand earlyrecovery and to leave markedplots forcontinuingobservation, with the intentof exploringthe ecological significance formangrovevegetation. of hurricanes Nicaragua (Fig. 1). Its climatecorresponds to the tropicalwet life zone of Holdridge (1967). The island extends15 km in a broad north-south arc and is close to 2 km wide throughoutits length; itsbaywardside is fringed in a band 0.1 to 1.0 km wide withmangrovevegetationgrowingon a substrateof fine-grained mineraland organicdeposits. Althoughtopographic reliefis negligiblewithinthe mangroveareaand mostoftheislandmaybe subject to occasionalflooding,the surfaceis not typically overwashedat hightide.The mangroveswould be categorizedas "'fringeforest"in the typologyof eitherLugo and Snedaker(1974) or Cintr6net al. (1985). Movingwestwardat 15-16 km hr-I alongparallel 12?N, HurricaneJoan struckIsla del Venado on 22 October 1988. Meteorological data are not STUDY SITE AND METHODS availablefortheislanditself,but Bluefields, located Isla del Venado is an elongatedbarrierislandfront- directly acrossthe bay, experienced sustainedwind ing theBay of Bluefieldson theCaribbeancoastof speedsof 2 17 km hr-Inearthecenterof thestorm 377 Mangrove Regeneration TABLE 1. Nicaragua. striptransects, Isla del Venado,Blliefields, inposthuirricane Trees(-2.5 cmDBH) encountered Transect2 TransectI Species # Avicenniagerminans Lagunculariaracemosa Pellicierarhizophorae Rhizophoramangle Total 6 10 0 13 29 Y 21 34 0 45 10( # 17 8 0 1 26 Transect3 5 Y 65 31 0 4 100 Total 7 1 1 2 11 64 9 9 18 100 Y 30 19 1 16 66 45 29 2 24 100 is consideredunusual for withgustsexceeding250 kmhr-I(INETER 1988). of Pellicierarhizophorae Rainfallin Bluefieldstotaledmore than 400 mm the Caribbeanarea (Roth & Grijalva 1991). Tree size and densityestimatesare summarized forthe period of 21-23 October and tidal surge therewas substantial(INETER 1988). Immedi- in Table 2. Stem densityand basal area varied in thelarge amongtransects as reflected atelyfollowingthe stormobserversreportedthat considerably is associatedin part thebay had been standarderrors.This variability throughout themangroveforests killed; seven monthslater therewas no sign of withthe low numberof treesin transect3, nearly otherthanthe one-halfof whosesurface(233 m2of 500 M2) was visiblefrom50 m offshore recovery sp.) occupiedby a thickcoverofAcrostichum sp. Values largegreenfrondsof leatherfern(Acrostichum among the apparentlyleaflesstrunksof the man- in Table 2 representminimumestimatesforthe stand since theyexclude treesbroken pre-existing groves(pers. obs.). On 16-17 March 1990 woodyvegetationwas below 1.3 m, of whichthreesproutingspecimens werecounted;fallentrees,ofwhich thedam- ofLagumncularia crossing sampledalongthreestriptransects Rhizophora; anyindividuals aged mangrovefringeon Isla del Venado (Fig. 1). therewas one sprouting The islandwas chosenas a studysitebecauseof its uprootedand blownfromthesamplearea,ofwhich as well no evidencewas noted;and dead stemslyingacross in thepathof thehurricane locationdirectly as the appearanceof ratheruniformphysicalcon- but not appearingto have been rootedwithinthe fromrandomly strips. ditionsalongitslength.Originating To permitcomparisonwith mangroveforests locatedpointson the island'swestshore,thesamdue magneticeasttodetect elsewhere,complexityindices (Holdridge 1967) plingstripswereoriented based on thesestripsare presentedin Table 3. The possibletopographiczonationin thevegetation. to measured5 m x 100 m, or 0.05 indices,whichare compositevaluesproportional Striptransects ha each. All woodyvegetationrootedwithinthese species number,stem density,maximumheight, areaswas recorded,in 2 categories.For individuals and basal area (totalstemcrosssectionalareaat 1.3 - 2.5 cm DBH (bole diameterat breastheight,or m above ground),ofstands,arerecordedhereboth 1.3 m above groundlevel), recordwas made of forthe standardtreecomponent(DBH - 10 cm) (dm), species,DBH (cm) and using a smallerminimumdiameter(2.5 cm) distancealongthetransect measuredwithdiametertape, approximateheight as adapted formangrovevegetationby Pool et al. (ocular estimateto nearestmeterby experienced (1977). Complexityindicesare computedforeach doublingstemnumbersand basal conditionof main stem(brokenvs not), stripseparately, forester), vs poorlyrefoliat- areasto conformto thestipulated0.10-ha transect. class(wellrefoliated and recovery ed vs dead). For smallerindividualsonlyposition (Althoughsuch extrapolationnormallywould be of (as above), species,height(to nearesthalf-meter), problematicaldue to the nonlinearrelationship and origin(sproutvs seedling)werenoted.Patches ofdead wood fernand accumulations ofAcrostichum TABLE 2. Structuralparamieters (? 1 SE) ofprehur;rcane werealso recorded. RESULTS miangrove forest, Isla clel Venado, Bliefieldls, Nicaragua. AverageDBH: 14 (?4) cm PRE-EXISTINGSTAND.-There were 66 individuals Heiglhtof tallesttrees:25 m (incl I brokenat thislevel) >-2.5 cm DBH (hereafterreferredto as "trees") in Tree density:440 (? 111) ha' Basal area: 14.88 (+9.29) m' ha-' Fourmangrovespecieswere Tree species:4 thethreestriptransects. in Table 1; thepresence as enumerated represented, 378 Roth TABLE 3. Complexity indicerof prehurricane mangrovevegetation,Isla del Venado, Bluefields,Nicaragua,and of fringe(F) and overwash(0) mangroveselsewhere.b Complexityindex Mangrovelocation Isla del Venado, 1 Isla del Venado, 2 Isla del Venado, 3 Florida Florida Ceiba, PuertoRico Aguirre,PuertoRico Punta Gorda, PuertoRico Isla Roscell,Mexico Sta. Rosa, Costa Rica Life zone' T Wet T Wet T Wet ST Moist ST Moist ST Dry ST Dry ST Dry ST Dry T Dry Type Trees -2.5 cm DBH Trees - 10 cm DBH F F F 0 F F F F 0 F 14.3 7.9 0.2 3.4 9.6 16.2 29.9 0.9 10.1 4.9 6.2 2.7 0.1 0.8 1.4 0.2 5.6 0.0 5.7 3.6 Holdridge(1967). Pool et al. (1977). c T = tropical;ST = subtropical. a b points.Locations speciesnumberto samplingarea,it is unlikelywith- and at a widerangeofintermediate in the mangrovecommunitythat largersampling of Avicenniaand Laguncularialikewiseextended unitswould have includedadditionaltreespecies; fromthe 5 m pointto theinlandends of the tranleftunchangedin the sects,with no segregationevident.Variance-ratio speciestotalsareconsequently positiveor negative weightings.)Complexityindicesreportedby Pool testsfailedto show significant data) amongthethree et ail. (1977) forfringeand overwashmangroves association(presence/absence inFlorida,Puerto principalmangrovespeciesusinga rangeofquadrat byhurricanes disturbed notrecently > W > Rico, Mexico, and Costa Rica are tabulatedfor sizesfrom25 m2 to 75 m2(X2005 95 those exceptthatAvicenniaand Rhizophorawere negatheiraveragescloselyapproximate comparison; ofprehurricane Isla del Vena- tivelyassociatedat the25 m2 size.Abundancevalues ofthereconstructions of Avicennia and Rhizophoraexhibitednegative do. using25 m2 (Spearman'srank No cleargroupingofspeciesintozonesor belts pairwisecorrelation parallelto shorewas apparentfortheprehurricane r = -0.349, N = 33, 0.01 < P < 0.05) and 75 the mangrovemost commonly m2 (r = -0.713, N = 11, 0.01 < P < 0.05) stand. Rhizophora, band,was indeed quadrats.The singleadult of Pellicierawas found an outermost reportedas forming foundin the first5 m of each transect;but it was 28.2 m fromthe water'sedge. also encounteredas far fromshore (100 m, the as anyoftheotherspecies DAMAGE TO PRE-EXISTING STAND-Trees in thesaminnerlimitofthetransects) by the heavydamageinflicted ple stripsmanifested hurricane; severedbranchesand twigshad leftmost specimenswith bare, open crowns.Trees of each samples,Isla del oftreesin mangrove TABLE 4. Recovery class and conspeciesare enumeratedby recovery afNicaragua,17 months Venado,Bluefields, in 4 stem Tables and dition of main 5. Forty-five terHurricaneJoan. percentof the treeshad brokentrunks,and only Number of individuals 42 percentof individualswere found to be well class per recovery in refoliated17 monthsafterthestorm.Rhizophora thesestripshad higherproportions of dead, poorly Well Poorly refoli- refoliindividualsthan refoliated,and broken-stemmed Total Dead ated ated Species were Avicenniaor Laguncularia,butthedifferences not statistically significant 30 12 4 14 (X2 = 7.06, 4 df, 0.50 A. germinans 19 4 11 4 L. racemosa > P > 0.10 forrecovery category;X2 = 2.07, 2 1 0 1 0 P. rhizophorae df,0.50 > P > 0.10 forstemcondition;Pelliciera 16 8 5 3 R. mangle counts). excludeddue to insufficient 66 24 14 28 Total largerbasal diBrokentrunkshad significantly Mangrove Regeneration 379 Dead treesconstituted 36 percentof all stems Stemconditionof treesin mangrove samples, on samplestripsand averagedmorethantwicethe Isla del Venado,Bluefields,Nicaragua, 17 months afterHurricaneJoan. diameterof treesthatsurvived(21 cm vs 10 cm; TABLE 5. two-sideda = 0.0175), leavingonly32 percentof the basal area in live stemsafterthe hurricane. Number of individuals with main stem Species Broken Entire Total 11 10 0 9 30 19 9 1 7 36 30 19 1 16 66 REGENERATION.-Seventeen monthsafter HurricaneJoanstruckIsla del Venado,seedlingsof the threeprincipalmangrovespecieswere found growingplentifully throughout thedamagedstand exceptwithinaggregations ofAcrostichum fern,from whichtheywere virtuallyabsent (Table 6). Avicenniaseedlingswere most abundanton all samametersthanunbrokenones (21 cm vs 7 cm; two- pling stripsand constitutedover one-halfof this sided a = 0.001 1); by implicationit was probably regeneration, followedin totalnumbersby Lagunthe tallertreesof the prehurricane standthatwere cularia and Rhizophora;but populationdensityesmost likelyto sufferbreakage.Averageheightat timates did not differsignificantly among the thetimeof samplingdid notdiffer betweenbroken threespecies(8583 vs 3943 vs 2054 ha-' of fernand unbrokenstems,so the effect of thewindwas freearea; F = 3.96, a = 0.0801). Ten seedlings evidently one ofleveling.This effect was augmented of Pellicierarhizophorae were recorded."Stump" by survival,sincethemeanheightofwellrefoliated sproutswereuncommon,largelybecausemoststem individualswas significantly belowthatofremaining breakagehad occurred at higherlevelson thetrunks; dead trunks(5 m vs 10 m; two-sideda = 0.0044). thethreerecordedcasesof basal sprouting involved Recoveryclass forbrokentreesdid notvarysignif- Laguncularia. icantlybydiameternorbyheightat whichthetrunk Like the adults,the seedlingsshowedlittleevsnapped,but stembreakageitselfwas strongly as- idenceof segregation intozonesby species.No sigsociatedwith mortality(X2 = 18.43, 2 df, P < nficantoverallorpairwiseassociationamongspecies 0.001). occurrenceswas found in 25 m2 sectionsof the Among the unbrokentrunks,thosewithgood samplingstrips,althoughabundancevaluesforLarefoliation had smallerdiametersthanthosewhich gunculariaand Avicenniawerepositively correlated recoveredpoorlyor died (5 cm vs 8 cm vs 16 cm; withinthesesame sections(0.01 < P < 0.05). The F = 11.83, a = 0.000 1). Theywerealso ofshorter speciesof a givenseedlingwas associatedwiththe staturethan the unbrokentrunkswhichrecovered speciesof itsnearestadultwithinthesame strip(X2 poorlyor died (5 m vs 6 m vs 12 m; F = 4.4, a = 17.37, 4 df, P = 0.0016), but the narrowness = 0.02). of the stripsprecludedreliable determination of A. germinans L. racemosa P. rhizophorae R. mangle Total TABLE 6. SEEDLING Mangrove seedlingnumbers and densities byspeciesand striptransect, Isla del Venado,Bluefields, Nicaragua, 17 months afterHurricaneJoan. Number of individuals Transect1 Species A. germinans L. racemosa P. rhizophorae R. mangle Total Transect2 % 155 141 5 66 367 42 39 1 18 100 Transect3 % 541 266 3 99 909 60 29 0 11 100 Total % 235 49 2 56 342 69 14 1 16 100 % 931 456 10 221 1618 57 28 1 14 100 Seedlingdensity(individualsm-2) Averagedover: Entiretransect Acrostichum-free' area Transect1 Transect2 Transect3 Mean (? 1 SE) 0.73 0.94 1.82 2.18 0.68 1.28 1.08 (?0.37) 1.51 (?0.37) 380 Roth TABLE 7. as a grouppreComplexity indicesofposthurricane mangrove 3). Instead,mangrovecommunities lowerindicesthantypicalupland vegetation bystriptransect, Isla del Venado, sentsubstantially Nicaragua. forests withintheirsamelifezones(Holdridge1967, Bluefields, Complexityindexa a Transect Trees -2.5 cm DBH Trees -10 cm DBH 1 2 3 0.6 0.9 0.0 0.1 0.3 0.0 Holdridge(1967). nearestadult neighbors.However,the seedlingcohortappeared thus farto be reproducingat least the proportionsof speciesin the older stand; the numberof seedlingsperstripof a givenspecieswas significantly withthenumberof prehurcorrelated ricaneadultsof thatspecieson thesame strip(r = 0.78, N= 12, P < 0.01) and totalseedlingnumbers were positivelycorrelatedwith overalladult totalsforthe fourspeciesas well (r = 0.95, N 4, P - 0.05). Mean height of Rhizophora and Laguncularia seedlingswas 1.5 m (to nearesthalf-meter), with Lagunculariaregeneration fromtheother differing species in averaging2 m tall (F = 44.3, a < 0.0001). If all seedlingsbecame establishedafter the hurricane,theirheightsrepresentan average growthof at least 1 m yr-'. Seedlinggrowthrate may be somewhatlower than heightsindicatein thecaseofRhizophora, whosepropagulesarealready typicallya few decimeters"tall" beforebecoming rooted.Fieldobservations didnotdistinguish whether anyrootedseedlings thestorm, mighthaveweathered but it is curiousthathistograms of seedlingheights forall of thethreeprincipalspeciesappearbimodal with the small second peak at 3 m; if theseless numeroustallerindividualswere not established thentheirheightgrowthhad priorto thehurricane, exceeded2 m yr-'. Complexityindicescalculatedforthe posthurricanestandare shownin Table 7. On theaverage, theseare morethan an orderof magnitudelower thantheirprehurricane in Table 3. counterparts DISCUSSION As reconstructed usingHoldridge'sindex,thestructuralcomplexity of themangroveforestexistingon Isla del Venado priorto HurricaneJoan was comparableto thatof fringe in the mangroves elsewhere hemisphere, withno differentiation evidentin complexityindexaccordingto climaticlifezone (Table Pool et al. 1977). Low speciesdiversity, reflecting the physiological challengesof the mangrovehabitat,accountsin partforthis;but thetreesof mangroveswampsare also generallysmallerin height and averagegirththan theirupland counterparts. Therewould be no inherent reasonto expectmangrovestands,givensufficient time,to developsmaller treesthanotherforests eveniftheirgrowthwere slower;but a greaterfrequency of perturbation of mangroveforestscould accountforsucha discrepancy.Periodictropicalcyclonescharacterize thearea occupied by mangroveecosystemsand have long been proposedas a limitationto theseforests'development(Egler 1952). To the extentthatstorm winds lose forcecrossingland, one would expect theiroverallinfluenceupon upland ecosystems to be less pronounced. HurricaneJoanset back standdevelopmenton Isla del Venado by selectively breakingand disproportionately killingthe largertrees.Thirty-six percentof thetreeson thesamplearea had died, representing fully68 percentof the basal area of the pre-existing stand.Treesshowingbestrecovery17 monthsafterthe stormwerethoseof shortstature and small diameter.These patternscontributed to the sharplydiminishedcomplexityindex forthese forestsafterthe hurricane. Similarresultsare reportedelsewhere.Wadsworth(1959) foundthat saplingstandsof white and blackmangrove suffered negligible damagefrom a hurricane whichkilled 59 percentof the treesin neighboring pole stands.Craighead(1971) noted that individualsless than 2 m tall were the only mangrovesto escapecompleteinitialdefoliation by inFlorida.Wunderleetal. (1992) found hurricanes thatdamage to mangrovesin JamaicafromHurricaneGilbertwas proportionately greaterin the trees. larger-diameter The implicitassumptionthat any dead trees foundon Isla del Venado had succumbedto the It was not possibleat hurricanewarrantsscrutiny. the timeof samplingto distinguish betweenstems killed by the stormand dead trunkswhichmay have existedwithinthe stand priorto Hurricane Joan.Data compiledbyJimenezetal. (1985) from numerousmangrovestandsshow a highlyvariable percentageof standingdead trunks,averaging26 The valto "normalmortality." percent,attributed ue of 36 percentofstemsfounddead in thepresent studyis well withinthe cited range (z = 0.60); however,the diameterclassesmost affecteddiffer Mangrove Regeneration 381 considerably.As Jimenezand coworkers(1985) impliesthatthe prehurricane tionin the regrowth interactions, standwas itselfearly-successional, fromcompetitive pointout, mortality thenso mustbe in all mangroveforestsin theregion,and truesuccesand diseasetendsto be concentrated herbivory, thesmallersuppressedstemsofa givenassemblage, sional changewould depend upon the mangroves so that standingdead treesfromsuch "normal" eventuallyalteringtheirhabitatsin such a way as causes averageonly 19 percentof the basal area of to permitestablishment of a different set of (nonthe standstheylist. The factthat dead stemson mangrove)species.Indeed,mostdiscussionofmanprimary Isla del Venado had an averagegirthmore than grovesuccessionhas focusedon protracted landbuilddouble thatof live ones and made up 68 percent successioninthecontextofhypothesized that ing and spatial zones interpreted as seres,not reof basal area on samplestripssuggestsstrongly in sponseto canopyremovalby disturbance;but the treemortalitytherewas primarilycatastrophic appears more typicalof timescale of stormeffects may tendto eclipsethe origin.Chronicmortality (Jim6nez etal. 1985) andonesin influence of moregradualgeologicprocessesas well basinmangroves etal. 1978) wheresalt as rendering aridenvironments (Cintr6n maladaptiveforvegetationof tropical stress is likelyto be moreacute. coaststhe traitstypicalof "climax" species. forest, blowdealttheformer Despitethesevere One would expectfrequentstormdisturbance as a to favorspeciescapable of constantor timelyflowarenotthreatened evidently thesemangroves densities ering,abundantseedingor sprouting,fastgrowth seedling giventhatestablished community, thestand.Silvi- in openconditions, maturity. and earlyreproductive alreadyappearampleto restock islim- The threeprincipalCaribbeanmangrove mangroves withAmerican cultural experience speciesshare has proveneffectivethese"early-successional" ited,butnaturalregeneration ofshade, traits.Intolerant ofstandsin Puerto theygrowquicklyas seedlings,as demonstrated portions in replacing harvested in (LunaLugo silviculturalstudies (Marshall 1939, Wadsworth 1959)andVenezuela Rico(Wadsworth in SouthAsia 1959). Theirflowering is precociousand all three 1976). Data fromseveralcountries adequatetorepop- floweryear-round considered indicate thedensities (Marshall1939, Little& Wadsin worth1964), but withpeaks whichin Floridaand theretheregeneration ulatemangrove forests; "abun- Panama producecopiouspropagulesbetweenAuisconsidered mangroves restocked naturally from605 gust and October (Craighead 1971, Rabinowitz densities areanywhere dant"ifseedling ha-' (Liewetal. 1977, 1978a, Tomlinson1980)-precisely the seasonof to over50,000individuals re- greatesthurricaneprobability(Neumann et al. laws requiring FAO 1985). Threecountries' postharvest1981). regenerated plantingof inadequately of 1667 to standsstipulatedensities Fromthelittlecomparativeevidenceavailable, mangrove man- adaptationsto wind disturbanceseem to be dis10,000plantsha-' (FAO 1985).IfCaribbean inthisrespect, thentherange tributedamongthespeciesin an unevenbut rather arecomparable groves ha-' overmostofthe compensatory of9400 to 21,800 seedlings fashion(Table 8). Thus Rhizophora forthestand manglehas provenin some cases themostresistant areashouldbe morethansufficient The onlyapparent to wind damage (Wadsworth& Englerth1959, on Isla del Venadoto recover. whichcovered Wunderleet al., 1992), but its olderbranchesare obstacleto thisis Acrostichum fern, spp. incapableof sproutingoncebroken(Noakes 1955, of thesamplearea;Acrostichum 28 percent in openareasofmangrove for- Wadsworth 1959, Tomlinson 1980); the other becomeestablished intractable weedsbyforestersmangrovespecies coppice well (Marshall 1939, estsandareconsidered worldwide (FAO 1985). on the Wadsworth1959). Lagunculariaracemosa, evidentin these other hand, is considered least wind-resistant The processof regeneration thusfarfromtheconventional(Wadsworth& Englerth1959) but is the superior differs mangroves estab- sprouter(Wadsworth1959). L. racemosaseedlings succession. of secondary Seedlings portrayal afterthestormwere appearto growfasterin theopen thanthoseof the lishedin thefirst17 months thesamepropor- otherspecies(Marshall1939, Ball 1980), but they ofthesamespeciesandin nearly tionsas thetreesof thepreviousstand;no new also have been foundthe mostintolerant of shade "pioneers" hadappearedandno "later-succession(Egler 1952, Wadsworth1959, Ball 1980) and standhad yetbeen therefore al" speciesfromthe former the least likelyto existbeneatha canopy Giventhat at thetimeofa disturbance. in theemerging generation. eliminated Lagunculariaalso tends age to suffer communities ofwhatever thehighestpercentseedlingmortality mangrove (DaCaribbean related totheseanda fewclosely species vis 1940, Rabinowitz1978c, Ball 1980). Avicenarelimited speciescomposi- nia germinansis thoughtto be the least shade(Chapman1976), ifunchanging 382 Roth TABLE 8. Summary ofreported relativeattributes ofthreeCaribbeanmangrove speciesrelatedtopersistence following hurricanes(references in text). Plus sign (+) indicatesthat data fromthepresentstudyaccordwiththe generalization; mninssign(-) indicatesapparentdisagreement; asterisk(*) indicatesstatisticalsignificance (P < 0.05) ofresultsin eithercase. Attribute Resistanceto windthrow R. mangle A. germnnans L. racemosa highest intermediate lowest intermediate lowest intermediate (+-) highest highest (+-) intermediate (-) Resistanceto breakage highest (-) Sproutingfromdamaged trunk Initialseedlingdensity lowest (+-) lowest (+-) (+-) Shade tolerance intermediate highest Seedlinggrowthrate intermediate lowest (+-) lowest (A-) (A-) Seedlingsurvivalrate highest (A-) (+a) intermediate highest (Aw) lowest (-) intolerant of thethree(Egler 1952) and to produce carefullydesignedfuturestudiescould lend additypicallyhighinitialseedlingdensities(Jim&nezet tionaldimensionsto Table 8 as well as providing a!. 1985) but to show theslowestseedlinggrowth morerigoroustestsforits claims. Timing of observationsis likelyto influence (Marshall 1939). Such patternscan be interpreted a rangeof nichesall compatiblewith perceivedpatternsas well: "poorlyrefoliated"inas illustrating while"well but orientedtoward dividualsmaydie orcontinuesprouting, disturbance, periodichurricane facetsand stagesoftherecovery refoliated"treesmaylatersuccumb.Relativeseedsomewhatdifferent lingdensitywill presumablyshiftat some pointin process. growthratesand survivalof Sample averagesfromthe presentstudy ac- responseto differential althoughsample initialpopulations;fromTable 8 one mightpredict cordedwithmostofthesepatterns, sizes were inadequatein most cases to projectthe thatAvicenniawill be surpassedin densityfirstby reliably toanylargerpopulation(Table Laguncularia and then by Rhizophora.Later on, relationships species can 8). Sproutingcapacity(based on percentrefoliation relativegrowthrates of the different of brokentrunks),"initial" seedlingdensity(17 continueto change(Ball 1980), inwayswhichlongwill help to clarify.Althoughthe monthsafterthe hurricane),and seedlinggrowth termmonitoring assuming componentspecies remainthe same, competitive rate(height17 monthsafterthehurricane on a givensubstrate mayeventually lead followedmostclosely interactions simultaneousestablishment) the predictedorderby species.Densitiesobserved to predominanceof one species,as Ball (1980) indicatedthat positsof R. manglein intertidalzones of Florida, duringa March 1991 reconnaissance Rhizophoraseedlingswere survivingconsiderably untilfurther disturbancerestoresthe earlierdiverbetterthan thoseof Lagunculariaand Avicennia. sity.Theseinteractions arelittlestudiedand deserve SuperiorshadetoleranceofAvicenniaseedlingswas closerattention. albeitweakly,byitslargerinitialnumber Posthurricane standdevelopment suggested, in mangroves of seedlings-3 m tall relativeto theotherspecies, is doubtlessmorerelevant to theirmanagement than whichcouldbe due to a greater densityofAvicennia changeswhichmay occuron a geologictimescale. can- The communities aroundBluefieldshave made use seedlingshavinggrownin beneaththeformer opy. Adult Rhizophoradid not show the lowest ofall fourlocal mangrovespeciesto varyingextents proportionof broken stems; and examples of forfuel,carvedobjects,construction materials,and werescantforall species.Speciesattri- tanning,and evidencepersistson Isla del Venado windthrow butes and availabilityof propagulesundoubtedly of sporadicpast cuttingof selectedtrees.Fromthe of storm initialresultspresentedhere it would appear that interact withotherfactorssuchas severity and type of substratein producingposthurricane periodicsmallharvests, ifadjustedin size,position, patterns(Cintr6net al. 1978), so that and timingto encouragepatchesor stripsof regenregeneration Mangrove Regeneration 383 erationof preferredspecies,representa "distur- trees,the resultsof such inquirywould seem more bance" fromwhichmangrovestandsmightreadily pertinentto the conditionsin whichtheyactually a desirablecombinationof regenerate.The west coast of Isla del Venado is recoverwhile offering are presentlyan enormouslightgap of a sortwhich and productiveuse wherehurricanes protection frequent.Limitingthe size of the cut patchesand thesemangrovesappearwell adaptedto recolonize, shouldhelppre- and the developmentof its standswill providea avoidingAcrostichum aggregations of theirpostdisturbance vent spread of the fern,and the periodicallyre- continuingdemonstration plenishedgroupingsofseedlingsand saplingswould successionalprocesses. afterfuturehurpresumablyspeed standrecovery ricanes.Researchon the communityecologyand ACKNOWLEDGMENTS profwouldundoubtedly ofmangroves management de Recursos Direcci6n it fromthe experienceof local resourceusers,who JorgeBrooksof theNicaraguan lentthisproject manyforms y del Ambiente in turnmightbenefitfromcollaborationin testing Naturales MaribelPizzi,Laureana Rivera, and ofvaluablecooperation. and refiningpossible silviculturaltreatments yRecursos oftheEscuelade Ecologia andManuelRomero erosionhazards. monitoring in participated Centroamericana, Universidad Naturales, In a classicstudy,Rabinowitz(1978b) com- allaspectsofthesampling de Staff oftheCentro process. de la CostaAtlantica y Documentaci6n pared seedlingsurvivaland growthof American Investigaciones Thanks inBluefields. support logistical generous mangrovespeciesbeneaththe canopiesof different provided reviewer areduealsotoD. JeanLodgeandananonymous speciesof adults; but she suggestedthata logical forveryhelpful ofthispaper.The on a draft comments next step should be to examine theirgrowthin fieldwork wassupported byNSF grant#BSR-8917680 of these toJohnVandermeer. treefallgaps. Given the shade intolerance LITERATURE CITED Everglades.Q. J. Fla. Acad. Sci. 30(1): T. R. 1967. Effectof HurricaneBetsyon the southeastern 10-24. of secondarysuccessionin a mangroveforestof southernFlorida.Oecologia (Berl.) 44: BALL, M. C. 1980. Patterns 226-235. por huracanes: de la selva de la costa atlanticanicaragiiense BOUCHER, D. H. In press. Frecuenciade perturbaci6n una vez en el siglo. Wani (Managua, Nicaragua). 1990. HurricaneGilbert'simpacton the naturalforestsand Pinuscaribaea BUNCE, H. W. F., AND J. A. McLEAN. plantationsofJamaica.Commonw.For. Rev. 69(2): 147-155. J. Cramer,Vaduz, Germany. CHAPMAN, V. J. 1976. Mangrovevegetation. and functional propertiesof mangroveforests.In 1985. Structural CINTR6N, G., A. E. LUGO, AND R. MARTiNEZ. ofPanama. IV series:monographs W. G. D'Arcyand M. D. CorreaA. (Eds.). The botanyand naturalhistory botany,Vol. 10, pp. 53-66. MissouriBotanicalGarden,St. Louis, Missouri. in systematic in PuertoRico and adjacent , D. J. POOL, AND G. MORRIS. 1978. Mangrovesofarid environments 5 islands.Biotropica10(2): 110-12 1. FairchildTropicalGarden Bulletin19(4): 1-28. and hurricanes. CRAIGHEAD,F. C. 1964. Land, mangroves, of Miami and theirsuccession.University 1971. The treesof South Florida.I. The naturalenvironments ALEXANDER, Press, Coral Gables, Florida. of HurricaneDonna on the vegetationof southernFlorida.Q. J. ,AND V. C. GILBERT. 1962. The effects Fla. Acad. Sci. 25(1): 1-28. DAVIS, J. H., JR. 1940. The ecologyand geologicrole of mangrovesin Florida.Papers fromTortugasLab 32. Carnegie Inst. Washington Publ. 517: 305-412. Washington, D. C. EGLER,F. E. 1952. Southeastsalineevergladesvegetation,Florida,and its management.Vegetatio3(4/5): 213- 265. Paper #4, Food and 1985. Mangrovemanagementin Thailand, Malaysia,and Indonesia. Environment Organizationof the United Nations,Rome, Italy. Agriculture of South Florida:present GENTRY, R. C. 1974. Hurricanesin South Florida.In P. J. Gleason (Ed.). Environments and past, pp. 73-81. MemoirNo. 2, Miami GeologicalSociety,Miami, Florida. of hurricaneEdith on marinelifein La GLYNN, P. W., L. R. ALMOD6VAR,AND J. G. GONZALEZ. 1964. Effects Parguera,PuertoRico. Caribb.J. Sci. 4(2 & 3): 335-345. bioticcommunities ofa tropicalcycloneon littoraland sub-littoral HEINSOHN, G. E., AND A. V. SPAIN. 1974. Effects and on a populationof dugongs(Dugongdugon(Muller)). Biol. Conserv.6(2): 143-152. HOLDRIDGE, L. R. 1967. Lifezone ecology.TropicalScienceCenter,San Jose,Costa Rica. INETER (InstitutoNicaragiiensede EstudiosTerritoriales).1988. Ciclonestropicalesy sus efectosen Nicaragua. In G. Cortes Dominguez and R. Fonseca L6pez (Eds.). El ojo maldito,pp. 193-214. EditorialNueva Nicaragua,Managua, Nicaragua. FAO. 384 Roth J. A., A. E. LUGO,AND G. CINTR6N. 1985. Tree mortalityin mangroveforests.Biotropica17(3): 177185. in Sabah. In C. B. 1977. Mangroveexploitationand regeneration LIEW, T. C., M. N. DIAH, AND Y. C. WONG. pp. 95-109. Universiti Sastry,P. B. L. Srivastava,and A. M. Ahman(Eds.). A newera in Malaysianforestry, PeranianMalaysiaPress,Serdang,Malaysia. 1964. Commontreesof PuertoRico and theVirginIslands.Agriculture LITTLE,E. L., JR., AND F. H. WADSWORTH. ForestService,Washington,D.C. Handbook #249. U.S. Departmentof Agriculture, 1974. The ecologyof mangroves.Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst.5: 39-64. LUGO, A. E., AND S. C. SNEDAKER. M. SELL, AND S. C. SNEDAKER. 1976. Mangroveecosystemanalysis.In B. C. Patten(Ed.). Systemsanalysis and simulationin ecology,Vol. III, pp. 113-145. AcademicPress,New York, New York. 50: LUNA LUGO, A. 1976. Manejo de manglaresen Venezuela. Boletindel InstitutoForestalLatino-Americano 41-56. of the treesof Trinidadand Tobago, BritishWest Indies. OxfordUniversity MARSHALL, R. C. 1939. Silviculture Press,London,England. NEUMANN, C. J., G. W. CRY, E. L. CASO, AND B. R. JARVINEN. 1981. Tropical cyclonesof the North Atlantic National Weather Service, Ocean, 1871-1980. U.S. National Oceanic and AtmosphericAdministration, Washington,D.C. of the mangrovetype growthand obtainingnaturalregeneration NOAKES, D. S. P. 1955. Methodsof increasing in Malaya. Malay. For. 18: 23-30. in Florida,PuertoRico, Mexico, of mangroveforests POOL,D. J., S. C. SNEDAKER, AND A. E. LUGO. 1977. Structure and Costa Rica. Biotropica9(3): 195-212. of mangrovepropagules.Biotropica10(1): 47-57. RABINOWITZ, D. 1978a. Dispersalproperties the relationship of concerning 1978b. Earlygrowthof mangroveseedlingsin Panama, and an hypothesis dispersaland zonation.J. Biogeogr.5: 113-133. 1978c. Mortalityand initialpropagulesize in mangroveseedlingsin Panama. J. Ecol. 66: 45-5 1. on the Caribbeancoast ROTH, L. C., AND A. GRIJALVA. 1991. New recordof the mangrove,Pellicierarhizophorae, of Nicaragua. Rhodora 93(874): 183-186. of recenttropicalcycloneson the coastalvegetationof Mauritius.J. Ecol. 50: 275-290. SAUER, J. D. 1962. Effects of HurricaneHattie on the BritishHonduras reefsand cays,Oct. 30-31, 1961. STODDART, D. R. 1963. Effects AtollRes. Bull. 95. PrintingOffice,Allston, TOMLINSON, P. B. 1980. The biologyof treesnativeto tropicalFlorida.HarvardUniversity JIMENEZ, Massachusetts. of HurricaneHattie, 1961, on the caysof BritishHonduras.Z. Geomorphol.7(4): D. E. 1963. Effects 332-3 54. of white mangrovein PuertoRico. Caribb. For. 20(3/4): 1959. Growthand regeneration WADSWORTH, F. H. 59-71. of the 1956 hurricaneon forestsin PuertoRico. Caribb. For. 20(1/ , AND G. H. ENGLERTH. 1959. Effects 2): 38-51. effects of HurricaneGilberton terrestrial 1992. Short-term WUNDERLE, J. M., JR., D. J. LODGE, AND R. B. WAIDE. bird populationson Jamaica.Auk 109. 148-166. VERMEER,