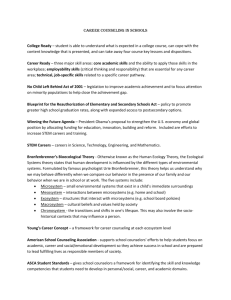

The Bioecological Model of Human Development

advertisement