Activity E1.1 - American Association of Physics Teachers

C. Student Investigations with Embedded Instructor Notes

Investigation E1: Batteries and Bulbs

15

Investigation E1: Batteries and Bulbs

Goals: Observe the behavior of batteries and bulbs when connected. Begin developing ideas about how electricity works.

In this first investigation, students will develop basic criteria for the operation of simple electric circuits. In addition they will become acquainted with the behavior of series circuits with two and three bulbs. In addition to observations that can be made of bulb brightnesses, they will learn to use a simple compass as an indicator that something is happening in the wires of the circuits they observe. They will also formulate several models for electricity and critically examine them with respect to past experience and observations of circuits which they construct in lab and in class.

As mentioned above in Section II.A. of this module, we find that generally students do not make distinctions in electricity such as those we make between current or energy or potential difference or voltage. While a few of them may make use of electrical terms, even those students are often found to use the terms interchangeably, which suggests a lack of differentiation. They tend to use the term "electricity" in a generic way as a

"stuff" that comes from a source and moves through the wires and is used up. Because it is their ideas and the change in their ideas that are the focus of our efforts, we start this unit using the term "electricity" as they would use it, in so much as we understand their usage. One of the goals of this unit will be to expose students to situations which do not support the notion of electricity as something that comes from the battery and is used up.

Most of the time in these activities is spent on students considering their own ideas, first individually in the context of making predictions, next in the light of the ideas and predictions of others, then, after making observations, in the light of those observations in contrast with their original predictions. It is extremely important that you impress upon the students that trying out the question with the apparatus is not to be done until after the thinking, writing, and discussing of the ideas in the first two steps of each activity.

The process of comparing one's ideas with those of others is extremely important to the success of this process for most students. As a result lab groups should never be fewer than three people in size. The preferable size is four or five people. Six tends to be too large for at least two reasons: It takes time for all six to get their ideas aired, and for them all to see and try the apparatus slows progress drastically. Frequently lab rooms and furniture do not conveniently accommodate six-person groups.

Because we want them to write down their ideas as they work through these activities and then we want them to be able to annotate these ideas during class discussions that follow the activities, we have provided a wide right-hand margin on the handouts for them to insert their class notes.

Electricity

Instructor Materials

E1(1)

©2001 American Association of Physics Teachers

16

Notes

©2001 American Association of Physics Teachers

E1(2)

Electricity

Instructor Materials

17

Activity E1.1: What conditions do you think enable the bulb to light?

(Seat Activity/Discussion)

In this activity the students confront the conditions for lighting the bulb. When it comes time in step 3, many will not be able to get the bulb to light at first. Be patient.

Encourage them not to become frustrated. The fact that some groups will be able to get a lit bulb early lets the others know that it can be done. The fact that others have a harder time is partly a measure of the extent to which their ideas about electricity match the actual behavior of this class of phenomena. We believe that being too quick to help them over this frustration by giving clues or heightening the frustration by cutting them off before they find how to do it does irreparable damage to the students by letting them believe that something at the very start is beyond their ability to handle without expert help.

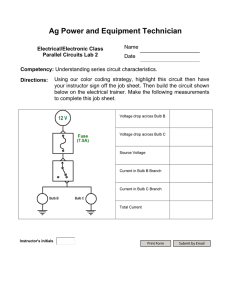

Equipment: 1 battery (D-cell), 1 piece of wire with both metal ends exposed, and

1 bulb (oblong #47).

1.

?

WHAT'S YOUR IDEA? What arrangements of battery, bulb, and wire do you think will enable the bulb to light? Imagine that you have a single battery, a single bulb, and a single piece of wire. In the space below make a diagram of these three objects arranged so that the bulb will light. Describe in words what you are trying to represent in the diagram and say why you think this arrangement will work—in other words, why do you think the arrangement will light the bulb?

Use pictures of the battery and bulb as shown above and use a line to represent the wire as you draw your diagram.

As has been mentioned before in these materials, the focus of our effort is for the students to finish having reached different understandings of the phenomena than they do when they start. For them to effectively change their ideas and have a clear view of the differences involved, they need to examine their initial ideas which means they must be made explicit or be expressed. You should make every effort to get them to make a drawing or two of configurations that they think might result in the bulb lighting. In addition, you should try to get them to think about why the configuration(s) might work; maybe because it looks like how a lamp works or maybe because it's based on some model or idea they have about electricity.

E1.1(1)

Electricity

Instructor Materials ©2001 American Association of Physics Teachers

18

It is important that this self-examination go on for several reasons. If they are not aware of their initial reasoning, they are likely to be limited by aspects of that reasoning, which are not explicit to them. Having committed to their initial reasoning which they made explicit, it is all the more intriguing and disequilibrating when their predictions, based on that reasoning, do not occur.

Finally, the significance of new ideas about the phenomenon does not stand out so clearly when there is nothing explicit against which to contrast the new ideas.

It is important for students to examine their own ideas first before being asked to speak with other students. Often one's own ideas can be lost in the conversations. It is also the case that many students do not feel comfortable speaking out before thinking and those who do would benefit from pausing to consider their ideas before speaking out. These students suffer without this option, and their ideas are a valuable and necessary contribution to the class.

You should let the students know that the activity sheets and what the students write on them are intended to be a journal of each student's ideas as the unit progresses. The students should be able to look back at these notes and be able to describe the history and evolution of their ideas about electricity during this unit. We advocate that you let them know at the beginning that you are not going to check these notes to see that they are predicting correctly or writing down some specific answers that you want them to write and that, instead, you are going to be checking to see that they are writing down ideas and why those ideas seem reasonable at the time. You also want them to make notes when they decide to abandon ideas that they have held and why it made sense to abandon those ideas at that time.

As for this specific task, you should hold up or otherwise show a set of the apparatus which you will hand out later. You are showing them the apparatus

(a battery, bulb, and wire stripped at both ends if insulated) so that they can be more sure of their task, but do not hand the apparatus out yet.

There are a fair number of combinations and permutations that the students can come up with as they are not constrained by what they do not yet understand. Hence, they have three objects each of which have two ends or attachment points, and they seem to find it possible to attach one, two or three ends at the same point and where possible to attach two ends of something (the wire) to the same point on one or both of the other items. Some students at this point will not think of the bulb having two attachment points. This need not be pointed out by you as frequently as it is pointed out by their classmates or comes out in discussion later. Only if you sense that this has not happened should you very carefully attempt to get the students to bring it up.

©2001 American Association of Physics Teachers

E1.1(2)

Electricity

Instructor Materials

19

2.

??

Circulate among the students as best you can. Answer any procedural questions like "Is this the sort of thing we are supposed to draw?" but not any questions involving content such as "Is this right?" or "Does it seem reasonable to you?"

Give no indication of what you think of the correctness of the idea or what the configuration should be at this point. Be encouraging.

WHAT ARE THE GROUP'S IDEAS? Listen and look as the members of the group describe arrangements that they think will light the bulb. Pay careful attention to why they think their arrangements will light the bulb. For each one that is different from yours, record the diagram and the reasons for that diagram. Try to come up with as many distinctly different arrangements as possible that will light the bulb. Continue on to the back of this page if you need the space.

Once everyone has had a chance to consider their own ideas, it is time for them to compare their ideas with each other. The emphasis should be on each student listening to the other students' ideas and reasons behind them in an attempt to understand what the other students are thinking about electricity at this point.

This will be the standard goal at this step of each activity. At this point in this particular activity, the goal is for the students to get the maximum number of ideas about electricity "out on the table" for consideration.

As instructor your task is merely to get the students to contribute ideas and act as the neutral moderator. You should go out of your way not to screen or filter student contributions. You should model what you want your students to do at this point, which is to be listening to and trying to understand the ideas presented.

In a very large class you can take directions from student volunteers while drawing the models on a transparency or on the board. Make sure that you also make notations as to why that configuration seemed reasonable to that student.

You should instruct the students to transcribe these drawings and their supporting reasons into their notes for future reference as a bank of configurations to try when the time comes. You can ask other volunteers for additional ideas regarding why that configuration might seem reasonable. If people want to suggest that some configuration will not work, then you should delay that discussion until later when the observations are made using the following instructions: They should write down notes for themselves explaining why they believe certain configurations will not work. These will be used in discussion in step four below.

When there seem to be no more new configurations or ideas, then it is time to try out the possibilities.

E1.1(3)

Electricity

Instructor Materials ©2001 American Association of Physics Teachers

20

3.

MAKING OBSERVATIONS: When the group is pretty sure of their ideas, try each configuration. Record whether the bulb lights for each arrangement. If none of the arrangements designed by the group result in the bulb lighting, then try some new ones. Make a diagram of each new arrangement that you try. Use the back of this sheet if necessary.

At this point pass out the apparatus. We keep ours in Ziploc TM bags. We use very inexpensive D-cells, and they are only used in this activity. The cells last several semesters, and they have less capacity to make the wires hot. We do this because it avoids all the hassles of loading them into the bags and then pulling them out for each lab. We want the freshest, heavy-duty batteries initially to avoid distracting behavior of the circuits when the batteries are weak. Later in the unit when the batteries do get weak, the students are in a much better position to think about the consequences of weak batteries, but initially this can be a serious distraction.

We have found that a number of students want to strip the wire at the middle to make certain of the configurations that they have drawn. We think that this should be allowed. You can accomplish this by having a few such pieces of wire available or by providing the original piece of wire with no insulation at all ( see the warning below ) or by allowing them to strip the middle of the wire themselves.

None of the options is without its own complications, but we think that the students should not be constrained by our notions of what is appropriate. They should be allowed to find what works and what does not for themselves.

You should think about the possibilities of making connections with just the wire between the ends of the battery, in which case, the wire can get fairly hot.

This is a frequent occurrence in this activity. With plastic insulated wires, we have had students notice that the wire gets hot and let go, but we have never actually had students receive burns. With either enamel, insulated or noninsulated wires of high gauge, this might be a possibility. You will have to tread a fine line between protecting the students from burns and encouraging or feeding an unwarranted fear of electricity. We believe the best thing is to use low-gauge (20 or less) wire with thick, plastic insulation (thermal as well as electrical).

If the class is large you can distribute the bags to groups of two, three, or four students. In smaller classes you can have a set for each student. In either case, every student should be expected to both try circuit configurations themselves and to work with at least one other student as they try these things, comparing notes, etc. The class should be encouraged to test all of the configurations that have been put up on the board and any new ones that occur to them while making careful notes about these new ones. They are to make notes regarding which ones light the bulb and which ones do not.

E1.1(4)

©2001 American Association of Physics Teachers

Electricity

Instructor Materials

21

4.

➥

They should also be encouraged to think about the initial question in the activity:

What conditions enable the bulb to light? In other words, what characteristics should any configuration have if it is to result in lighting the bulb?

MAKING SENSE: Compare your observations with your predictions. Did any of the configurations that someone in your group thought would light the bulb, not work? If so, with your group, make a list of reasons that were used to support those configurations which are now questionable. Put your list in the space below.

5.

With the class as a group-of-the-whole, you should act again as neutral moderator soliciting from the class their observations as to what did and did not light the bulb. You could start by asking about each of the configurations which were put up on the board or on the transparency in step two above. Allow for difference of opinion and be prepared to test each of the configurations in some sort of demonstration mode.

We have found it particularly effective to have a video camera set up with a video projector. The camera is aimed down at a table on which we can use the same apparatus as the students use to construct the configurations. The whole class can see what is being assembled, and all are free to "kibitz" your or some volunteer student's construction. We use this video projection equipment regularly throughout this unit. This has been our experience in classes of 150 students, and we expect that it would be useful in any setting with more than about 10 students.

With respect to the activity at hand, the tasks are to identify all configurations that do light the bulb, and all that do not, and achieve consensus on this list. The tasks and the experiences testing and establishing the list will be the basis for the students' thinking about conditions necessary for the bulb to light.

Drawing a Conclusion: What conditions enable the bulb to light?

WHAT'S YOUR IDEA? On the basis of your observations of arrangements which work and those which do not, try to decide on conditions that must be met to light the bulb and list these conditions below. Include reasons and refer to arrangements the group has tried for evidence in support of your conclusions.

?

At this point give the students a few minutes to individually think about what they have seen and heard. Ask them to consider what features the two groups of configurations have in common within themselves that might distinguish one group of configurations (the ones that lit up) from the other (the ones that did not).

E1.1(5)

Electricity

Instructor Materials ©2001 American Association of Physics Teachers

22

In the "seat activity" version of this activity, we usually ask the students when they think they have their ideas down to compare notes with their neighbors until we call the class back together as a group-of-the-whole.

6.

??

WHAT ARE THE GROUP'S IDEAS? Discuss with your group and try to reach some consensus on the conditions that must be met to light the bulb. List any new or changed conditions below. Consider things that you have observed so far in this investigation as you discuss this question.

Conditions for the bulb to light (group consensus):

At this point again you should be the neutral moderator. Explain that, first, the group should get all the ideas that seem reasonable to anyone "out on the table" and then they can discuss any criticisms of particular items afterward. Each idea should be written down for all the class to see. Make the list on the board as items are suggested by the students. You may find it useful to list characteristics which keep the bulb from lighting, too. Once all of the ideas seem to be out, then go back to each idea and ask for reasons why that condition seems reasonable.

The students will tend to talk to you, but you need to point out that they need to be talking to the other students and not to you. Go out of your way to be neutral and acknowledging, but not validating , of all the ideas contributed.

Finally, it is time for criticisms of the ideas that have been volunteered. Ask if any one has a problem with any of the conditions for lighting the bulb that have been stated. Those who do should be encouraged to indicate which one and why. This should be noted on the board or transparency. Supporters of the condition should be given a chance to respond. This should be allowed to go back and forth between the students, ideally as long as necessary, in order to reach some consensus. Be prepared to conduct tests with the apparatus under the video camera as the need arises.

This list of ideas being put up and then winnowed out should be the beginning of a list of ideas about electricity that is available to the class and acts as a source of reference points throughout the unit. Generally all ideas agreed upon by consensus of the class and those which are under contention should remain on the list. Those ideas which have by consensus been dropped from the list of useful ideas about electricity, can be brought up again, but generally should have lower status unless the class by consensus decides to restore them to the list.

We have found that in attempting to get them to summarize the conditions that survive debate, they generally come up with the following:

©2001 American Association of Physics Teachers

E1.1(6)

Electricity

Instructor Materials

23

1.

There has to be a closed, complete, circuitous path through all the items in the configuration.

1a.

Each item has two ends or connections, each of which has to be made use of in the configuration.

1b.

Only one end or connection for a given item can be used at any given point in the circuit. (It does not do to have both ends of the single piece of wire attached to the same connection point.)

2.

There needs to be a "power/electricity/energy" source; i.e., the battery, generator, or whatever is connected behind a wall outlet.

3.

Items in the circuit should be capable of carrying or conducting the electricity.

Two comments are in order here. The first is in reference to each circuit element having two connections or ends. When this is suggested, you should be on the lookout to encourage some student to ask about the bulb in this respect. Most of the students have no problems with the notion of the wire and the battery having two ends, but some do not notice that the bulb has such. For many, this is explained by another student as they are testing the configurations, but there are some unwilling to take another student's word for it. If you see any evidence of puzzlement on some student's face, encourage them to explain why they are puzzled and then solicit explanations from the class. Be prepared with a diagram of the bulb or have some broken ones that can be examined. The video camera setup can work surprisingly well in a large-class setting.

Safety Precautions

➠ Warn the students about the dangers of possible sharp edges on the glass.

The second comment is that we find it especially ineffective and inappropriate to insist that students use particular words in particular ways until they already have, by consensus or adopted common usage, a word or phrase that represents essentially the same idea and makes the same distinctions between itself and related ideas as the special word you want the students to use. Hence, insisting on use of the word "circuit" or a specific choice as to what the battery is the source of are inappropriate until the students have agreed on what these words mean. At the end of this activity, we find they have an idea which is the same as our notion of "circuit" and another which is equivalent to our notion of "circuit element," so we make those associations for them in the following definition.

Electricity

Instructor Materials

E1.1(7)

©2001 American Association of Physics Teachers

24

Regarding the term used to describe the source in the circuit, we believe that it does not do at this point to be particular about which term they use. We find that as many or more use the idea, "source of electricity," as anything else. Since

"power," "energy" and "electricity" are in this context undefined and undifferentiated by them, the choice should be left for later. For right now, let them decide. If you have a really thoughtful group, you might be lucky enough that they will decide what specifically to use for now and why. With great care, you might, if you are so inclined and if they have used multiple terms, raise the issue in the following way. Point out that during the discussion you have heard various people use the following terms to describe what the battery source is.

Then list them and ask, do all these things mean the same thing or should/can the class come to some consensus as to which one should be used? Be prepared to be the neutral moderator again. They can either reach consensus at this point or not, but you can add their conclusions to the list of ideas about electricity which the class will monitor during the unit.

DEFINITION: Electrical Circuit: An arrangement of electrical elements that meets the same kind of conditions as those necessary to light a bulb is called an electrical circuit.

The items in a circuit, which make up the circuit, are called circuit elements.

©2001 American Association of Physics Teachers

E1.1(8)

Electricity

Instructor Materials

25

Activity E1.2: Where is the circuit in a flashlight?

(Homework/Discussion)

Find a flashlight at home and take it apart, but don't destroy it. Figure out where all the parts of the circuit are that enable the flashlight to light up when turned on.

Make a sketch of what you have found and write a short essay (no more than a couple of paragraphs) with diagrams that explain your findings in the space below.

Reassemble the flashlight and bring it to school with you. (If you cannot find a flashlight, contact your instructor.) Be prepared to share your explanation with a small group of your classmates.

This activity is intended as an application of the ideas the students have developed in the previous activity. It should be assigned after Activity E1.1 has been completed by the class. We find that many students report at the end of the unit that this activity was one that they especially remember and like because of the opportunity it affords them to apply things that they have figured out. We make time in the next class period for them to share their explanations and flashlights with each other. This can be part of a more structured effort to help them refine their ideas by having them write these explanations and then to actually critique each other's explanations with feedback.

Frequently, they are surprised that part of the circuit seems to be missing. This usually happens with metal bodied flashlights because the metal body is the "return" portion of the circuit. We find that this surprise and the ensuing discussion help reinforce the notion of complete circuits and often result in a discussion of the notion of conductors and nonconductors which compliments what discussion there is of conductors and nonconductors at the end of Activity E1.1.

We do not include a specific activity on conductors and insulators in these materials. In development of this Electricity unit, we have tried such an activity. We found that the notion that "some materials can be used to complete a circuit and some do not" is already present in our students. By merely testing a number of items, few surprises are found and no new patterns or notions about the nature of matter or electricity result.

As a consequence we have chosen not to include a specific activity on this, and we find that this idea is a part of the discussions in Activities E1.1.

Electricity

Instructor Materials

E1.2(1)

©2001 American Association of Physics Teachers

26

Notes

©2001 American Association of Physics Teachers

E1.2(2)

Electricity

Instructor Materials