Managing Class Discussions

advertisement

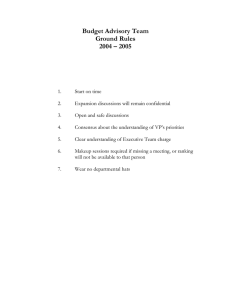

Unit 5 Managing Class Discussions Objectives 1. Distinguish discussion from other forms of student participation. 2. Understand the purposes of small group discussions. 3. Know how to manage effective discussions. 4. Know how to prevent problems in discussions. 5. Develop a plan for a class discussion. In the next two chapters, we will look at strategies in which students take center stage as active learners. In this chapter we will focus on managing class discussion. Class discussions are one important way to get students more involved in their own learning. The next chapter will focus on other forms of active learning. Critical Thinking Interruption Think about discussions in general, not only those that take place in a class setting. What makes a discussion a good discussion? List the characteristics of a good discussion. 2 Discussion Objectives Often class discussions involve relatively little discussion; the teacher asks a question then waits for someone to answer. Most students try to look busy by taking notes (on what?) and wait for this irritation to pass. A few students often carry the load in the discussion, as they probably have during the entire semester. In a study of 20 different classes involving a total of 579 students, Nunn (1996) found that the median percentage of time spent in student participation per class was 2.28%, and the median percentage of students who spoke was 25.46%. That is, most students do not talk during "discussions" and those who do, do not talk much. Let’s consider some teaching objectives that are best accomplished by involving all students in a discussion. If all or most of the students participate in a meaningful way in class discussions, you can be assured that the majority of your students are doing more than just memorizing facts. Rather, they may be thinking about ways to apply course information to their own lives. The major impetus behind the push for more active learning approaches in the classroom is the fact that students forget memorized facts and are more likely to recall meaningful lessons (Sikorski & Keeley, 2003). Learning to think requires practice. In order for critical thinking to occur, problem solving has to take place and decisions have to be made. According to McKeachie (2011) discussion gives students practice in thinking when they evaluate the logic of their own and others' positions, and develop applications of principles. When diverse viewpoints are present in a group, discussion and other active learning activities set the stage for students to explore varying perspectives on a given topic. For 3 example, men and women will learn more about gender role development when both genders are represented in a discussion, and even more when there is a diversity of cultural backgrounds. Finally, discussion is an occupational skill, like writing. Students should be aware that in business and professional life they will be taking part in discussions where their performance will be important. For more reasons to use discussion, see Brookfield & Preskill's (2005, p. 21-22) list of fifteen benefits associated with using discussion methods in the classroom. 4 Managing Effective Discussions "A discussion is an exchange of ideas where all members of the group have an opportunity to participate and are expected to do so to some degree" (Kramer & Korn, 1999, p. 99). Depending on the size of the class, even if the teacher did very little talking, there may be limits to the extent to which all students can be involved in a discussion. For larger classes, one way to give all students an opportunity to participate in discussions is to divide the class into small groups. There are several reasons that separating classes into groups may not be easy for a teacher. First, they may not be used to conducting classes this way, so the process seems awkward. The intact class, like the lecture method, is like a comfortable old shoe that they can just slide in and out of at their discretion. Second, teachers may be uncomfortable when they have less control over what happens in the class and discussion may go in unintended or noncourse related directions. In particular, there is a danger with discussion on topics like sexual orientation, ethnic diversity, religious diversity, and gender roles that generate a lot of student interest, but may result in a student making a comment that offends other students. Third, many teachers are challenged by students who either won't talk at all or dominate discussions. All these problems can be managed effectively with practice. 5 Forming Groups Size. Discussions are most effective in groups of 4-6. In theory, a class of any size can be divided into subgroups, but often there are limits imposed by time and space. There should be at least a little distance between the groups to prevent crosstalk during the discussion, and not all rooms are large enough for that. Time might be a factor if each group is to report its conclusion at the end of the discussion. Flexibility. In some rooms, chairs are bolted to the floor and in fixed rows with long tables extending in front of the chairs. While challenging, that arrangement should not prevent using small groups. For example, a group of four is formed when two students turn around and work with the pair behind them. In classroom with furniture that is flexible and easily moved, creating new seating arrangements can be fun and instructive for the class. Choosing group members. Students learn more when the diversity of a group’s members is greatest, so when possible use a strategy such as counting off to form groups rather than allowing students to form their own groups. Sometimes it is best to assign students to groups to insure diversity. In a discussion of gender issues, for example, you may want groups that include (or do not) both men and women. It might also be useful to form the groups based on some mixture of skill level or class performance. This type of intervention might enable students who are struggling with concepts to discover how successful students are thinking about the class material. 6 Promoting Participation and Preventing Problems. As an undergraduate, Jim was a shy student, so much so that he would avoid classes where he might have to talk a lot in class and give oral reports. For that reason he has a lot of empathy for students who are anxious about talking in class. We (Kramer & Korn1999, p. 101) offer these suggestions concerning shy students: The course description should clearly indicate that discussion will be expected, and this fact should be emphasized in the first class meeting. Help should be available for shy students either from the instructor or a student development center. Be accepting of degrees of participation. Students who need to confront their shyness need time to develop, and all of us have days when things are going terribly, and we prefer to remain quiet. Shyness may not be the only reason that students do not want to talk in class. Some may have speech disorders. Your university disability counselor should notify you about these cases and can provide suggestions for how to help these students participate. Other students may come from a culture that does not approve of public self-presentation. You might explore other ways for those students to express their views. The challenge for the teacher becomes how to promote full participation in discussions while encouraging active listening as well as talking, and preventing problems that commonly occur in groups. The following four strategies will help address such challenges: establishing clear ground rules, clarifying instructor and student roles, providing training in discussion skills, and offering alternative ways for students to participate in discussion, perhaps through the use of technology. 7 Establishing Ground Rules When a group agrees publicly on how to carry out its work, the reduction in ambiguity can promote class participation and help to maintain order in the classroom. Ground rules for discussions can be set either by asking students to participate in developing them or by suggesting a list that is open to modification. Some believe that having the class set the rules creates a sense of ownership and increases an individual student’s commitment to follow the rules. ______________________________________________________________________________ Activity: Earlier in this unit, you listed the characteristics or guidelines that you believe make a discussion good. Compare the list you wrote with the following discussion guidelines (adapted from Schwarz, 1994 by Kramer & Korn, p. 101-102). 1. Begin the discussion with a question that all members understand. 2. Expect some level of participation of everyone, while allowing that individuals may participate at different rates or levels. 3. Prevent domination of the conversation by one or two people. 4. Allow individuals to finish their thought; do not interrupt. 5. Listen. Concentrate on what others are saying rather than formulating your response. 6. Paraphrase and summarize to increase understanding. 7. Ask for and give the basis for opinions and observations. 8. Encourage divergent views; everyone may have a piece of the truth. 9. Be specific and use examples wherever possible. 10. Keep the discussion focused on the topic. 8 Now take a moment to create a list that combines your earlier list with those guidelines above that you find most helpful. What items should be added to this list? Should any items be deleted from your original list? ______________________________________________________________________________ Additional suggestions for ground rules and how to generate such rules can be found in Brookfield and Preskill (2005, p. 53-54) and Davis (2009, p.98-99). Following these ground rules will help to prevent many common problems, such as the dominant talker and groups going off on tangents that concern teachers. Instructor and Student Roles When a class is divided into smaller groups, the instructor’s role changes from being a discussion leader or group facilitator to being a supportive observer. In this role the instructor clarifies the discussion questions in the beginning, monitors the process and progress of each group, and, when the groups have finished their work, the instructor manages reporting, summarizes points across groups, and draws out the implications of the exercise during a discussion involving the whole class. Typically, each group selects one student to serve as facilitator to manage the discussion and hold the group members accountable for following the ground rules. Another student in each group is selected to serve as recorder with the responsibility to summarize and report on the main points brought out in the discussion to the class as a whole. Jason often tells students that he has yet to decide which group member is going to present the group’s findings to the larger class during group discussions. This strategy holds all students responsible for explaining the group’s conclusions. See Doyle and Straus (1982, p. 291-292) for a more in-depth discussion of the group discussion facilitator and recorder roles. 9 Teaching Discussion Skills Involving students in the management of discussions gives them an opportunity to learn valuable communication and group process skills. Frequently these are skills with which most students have little experience. It is worth devoting class time to the introduction, demonstration, and practice of most or all of the following skills: Active listening, including paraphrasing and summarizing, Keeping on the topic and managing interruptions, Accepting divergent views and managing conflict, Involving all participants and dealing with dominance, Facilitating discussion and enforcing the ground rules. The following is a process that Jim has used to help students learn how to be effective discussion participants in preparation for frequent discussions during the semester. There are several reasons for this process: to model management of discussion in the class as a whole, to generate items that form the basis for setting discussion ground rules, and finally, to show the limits of large group discussions. Jim asks students to generate a list of characteristics of a good discussion that should appear in the ground rules for class discussion and he records students’ suggestions on newsprint. If the class begins with students seated in rows, someone usually suggests that the discussion would be better if people look at each other. At that point if the group size allows and chairs are not bolted to the floor, he stops and has students rearrange the chairs so that students will be facing each other. During this discussion he has an observer (preferably not one of the participants) note how many people speak and roughly for how long. Later he contrasts the 10 extent of participation in the large group discussion with that when the class is divided into small groups. When the group (the class as a whole) agrees that the ground rules are acceptable, he posts them so everyone can see them. He also provides copies for everyone in the class so they can bring the ground rules to every class meeting. For the first few discussions it helps to remind the class to take these ground rules seriously. Telling students about skills needed in discussion is not as effective as showing how to use the skills. Ask someone with experience in group process to join you in modeling several of the ground rules. For example, your colleague can act the role of a dominant student. You can demonstrate what it means to be an active listener. Of course, this assumes that you are familiar with and experienced in discussion skills. If not, try to find a colleague who can help you or a workshop that will develop your skills. If you value active learning and want to accomplish the objectives for which discussion is best suited, then it is worth providing the class time to include this training early in the course. You will then want to include small group discussion regularly throughout the semester. Problems may still arise; however, remember that prevention is the best medicine, and students may need to be reminded of three basic ground rules at the beginning of discussions: First, that student opinions are welcome, and second, the importance of respecting the opinions of others, including that of the teacher; and finally, that comments should be directed toward comments made by others, not the individuals who made the comments. If you still have a problem, remember that this is your class, and it is all right for you courteously to interrupt a student. The rest of the class will appreciate that. Then talk with the student after class or before the next 11 class, saying that you value all constructive contributions and help the student to become more constructive. ______________________________________________________________________________ Activity: Refine your views on discussion Relate the information you just read about discussion to your philosophy and course objectives. Begin by reviewing your philosophy and selecting ideas that suggest where you stand on the teacher- and student-centered dimension. Is this where you want to stand? Write your response. Next look at the objectives you wrote for the course you used in the section on planning. Which, if any, of these objectives could be achieved using small group- discussion? How would you do that? Finally, list any problems that you personally anticipate when using class discussion? ______________________________________________________________________________ 12 Other Types of Class Discussions With today’s technologies there are ways that students can discuss information without having to face pressing concerns about feeling nervous in the presence of other students and the teacher. Many college courses today feature online discussions that students and teachers can visit at their leisure and post critical thinking questions, continue in-class discussions, solicit student opinions about current events as they relate to class material, post practice quiz questions for the students to discuss and/or raise questions about their assigned readings. Many course management systems, such as Blackboard, include tools for setting up discussion boards. Such discussion tools enable the instructor to set up smaller discussion groups, something that is particularly useful for large classes. Some teachers set up class email listserves for discussions; however, one caution is that if the class is large or the number of emails voluminous, managing and organizing of responses can be challenging. There is an ever expanding set of free Web 2.0 tools that support on-line discussions. For example, many instructors use blogs (e.g. Blogger) to support discussion of course readings or a tool such as VoiceThread that allows comments in audio, video or text formats. Twitter, which requires students to condense comments to at most 140 characters (tweets), is a microblogging tool that some instructors use as a discussion tool in and out of class sessions. Click here to see an example of how Twitter has been used to enhance classroom discussion. Regardless of the tool used for on-line discussions, the same challenges for managing face-to-face (f2f) discussions are often challenges in on-line discussions. Just as suggested for f2f discussions, Mary has students develop the rules they will use on-line to support good discussion. She divides students in large classes into small on-line discussion groups so that everyone has an opportunity to participate, and asks that one student facilitate the discussion and 13 another student report out on-line to other groups a summary of the group’s discussion. She models the responsibilities and strategies needed for each of those rules by facilitating the first on-line discussion and summarizing the discussion. She frequently privately asks students to ‘act out’ particular problem behaviors in the initial on-line discussion so she can demonstrate strategies for dealing with such behavior. In order to make all students accountable for participating in on-line discussions, a teacher might require a certain number of postings per student within a specified time period. If you use this strategy, you will want to provide guidelines for what constitutes a good posting prior to the beginning of the discussion in order to encourage quality rather than simply quantity of comments. Mary provides students with a rubric or set of guidelines that sets out her expectations of what constitutes a quality comment. Other strategies to generate discussion regarding class material that teachers have utilized with considerable success include the following: Encouraging students to attend office hours and discuss class material one-on-one with the professor and perhaps rewarding students for doing that; Giving students the opportunity to present their written thoughts or questions about class material by email or handwritten note. 14 Evaluating Discussions There are many reasons to use discussion in class and if these reasons are related to some of your objectives, you want to know if those objectives have been achieved. You may think that participation itself should be an objective and want to grade students on the extent to which they participate. These are some reasons not to grade participation: Talking is not the same as learning. Grading the number of comments reinforces only talking. Grading the quality of comments is highly subjective. It is difficult for the teacher to manage the discussion while evaluating the students. In many cases you are grading personality traits, so shy students are at a disadvantage. Rewarding, however, means that you encourage and recognize comments that are of high quality, as well as comments that indicate active listening. Small groups or the class as a whole can be rewarded for a good discussion. You can work with shy students to reward their less frequent comments, and perhaps reduce their shyness, whether in class, during office hours, or through on-line discussions. One area where grading may be appropriate is that of student preparation for discussion. For example, students might be asked to prepare summaries of sections of a reading assignment. Each student prepares a different section so that the group has all the information needed for the discussion. This puts pressure on each student to complete her assigned section, since without it, the entire group cannot complete its task. Evaluating whether a discussion achieved the stated objectives is a different matter. We will work on course evaluation in a later Unit and many of the techniques that we present there can be applied to the evaluation of discussions, (e.g., student writing and videotaping). Brookfield and Preskill (1999, p. 215-216 new edition?) provide a checklist of questions to 15 assess the teacher's ability to manage discussions. They (p. 218-220) also recommend using a "discussion audit" to assess "how well students have observed the rules of conduct they have evolved to govern the discussion process." They suggest requiring students to do audits on a weekly basis and to summarize the audits in a learning portfolio at the end of the semester. 16 Whole Class Discussions If a discussion is an activity in which all members of the group have an opportunity to participate, then there are clear limits on the size of the group involved. A General Psychology class with about 100 students in it and 75 minutes per class meeting gives each student less than a minute to talk. Given the realities of this situation, most students will not participate unless techniques other than those common in the frequently used lecture-discussion method, where the teacher occasionally asks a question and allows a few students to respond briefly are used. Using small groups in a large class as discussed earlier or having students work in pairs is one way to ensure that all students participate. The teacher might pose a question, ask students to reflect and write for a couple of minutes, and then exchange papers and discuss their ideas with a partner. After allowing a reasonable amount of time for this, the teacher may ask for a few volunteers to summarize one or two main ideas from their paired discussion, using that information for continuing the lecture. This has proven to be an effective way to get most students to address the task and make participation much more inclusive than in a typical "lecture-discussion." Productive Questioning According to Bain (2004), students are more likely to engage in a discussion when there is “something to discuss that the students regarded as important and that required them to solve problems (p. 127).” Asking good questions is important regardless of the discussion format. In the whole class situation, one of the most common questions asked is, "are there any questions?" The typical response is a sea of glassy eyes, even though many students may have questions. What can you do to encourage students to ask questions? 17 One solution is to have students write their questions and submit them at the end of class. An alternative strategy is to ask students, "what was the muddiest point in today’s class?" or "what things seemed most confusing in class today?" Review their responses, pick out the points mentioned most often, and go over these ideas again in the next class. For more detail on these strategies and many other practical suggestions, we recommend Angelo and Cross’s (1993) excellent book on classroom assessment. Productive questioning is not as easy as one might think, yet a teacher’s initial questions play a major role in determining how involved students will be in the subsequent discussion. You can be too general (e.g., What do you think of Freud’s theory?) or too specific (e.g., How many elements are listed on the periodic table of chemical elements?). Asking questions should fulfill some of your objectives and one way to do that is to plan most of your questions in advance. You also have to make decisions in advance on how you will handle the discussion process: Will you ‘cold’ call on students, or only call on volunteers? How long will you wait for an answer? A major mistake that many new instructors make is not allowing enough time for students to think and respond between the time a question is asked and the instructor provides the answer. What if there is no answer to your question, will you rephrase the question, follow-up with a more probing question, or continue to wait for an answer? Will you learn to be patient and bear the silence during which, you hope, students are thinking? Remember -- let your teaching philosophy guide you in making these decisions. The Fish Bowl To add more fuel to the fire when it comes to questioning options, we leave you with a potentially useful small group technique that can be used in large classes. This technique is called the fish bowl technique. First, present a question for discussion and ask all students to 18 write a response to the question. Then ask for volunteers to have a discussion in front of the whole class. Invite the volunteers to come to the front of the room and sit in a circle or semicircle. The instructor facilitates the discussion. After the fish bowl group has responded, ask the remaining students (the audience) for additional comments. Jim used this technique in a discussion of gender role socialization. A class of 80 students filled out a check list of statements about being masculine or feminine (e.g., boys don't cry). They reported whether they heard these things as children and if they would tell their children these things. Then they wrote what the best and worst things are about being a man or a woman. Next, two groups of five students responded to questions based on the check list of statements; one group was all female and the other all male. After each group discussed the questions, the other group responded, usually with extensive criticism of the views of the other biological sex. Finally, the audience added comments. Students usually view the fish bowl technique as a creative exercise, and more importantly, it’s a technique that promotes critical thinking and active processing. Additional strategies for effectively handling discussions can be found in Bain (2004, pp. 126 – 134) ______________________________________________________________________________ Activity: Creating your own unique discussion format We have covered a considerable amount of material related to discussion methods and their benefits for students. Remember however that you are an individual with a unique teaching style. Record your own personalized method for generating discussion in your classes. You may find some of the methods discussed in this chapter useful, but you will want to personalize the strategies you will use based on your teaching philosophy. ______________________________________________________________________________ 19 Looking Ahead Discussion is one method for promoting active student learning. The next unit will focus on additional teaching strategies that use small group activities to promote active learning. Many experienced teachers are either unaware of small group activities or are reluctant to use them. Meyers (1997), Millis (2002), and Myers & Jones (1993) provide an introduction to and review of a variety of active learning activities. 20 References Angelo, T. A., & Cross, K. P. (1993). Classroom assessment techniques: A handbook for college teachers. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Bain, K. (2004). What the best college teachers do. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Brookfield, S. D., & Preskill, S. (2005). Discussion as a way of teaching. (2nd Ed.) San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Davis, B. G. (2009). Tools for teaching.(2nd Ed.) San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Doyle, M., & Strauss, D. (1982). How to make meetings work. New York: Jove Books. Kramer, T. J., & Korn, J. H. Class discussions: Promoting participation and preventing problems. In Perlman, B., McCann, L. I., & McFadden, S. H. (1999). Lessons learned: Practical advice for the teaching of psychology. Washington, DC: The American Psychological Society. Meyers, S. (1997). Increasing student participation and productivity in small-group activities for psychology classes. Teaching of Psychology, 24, 105-115. Millis, B. J. (2002). Enhancing learning -- and more! -- through cooperative learning. Idea Paper No. 38. Manhattan, KS: Kansas State University, Center for Faculty Evaluation and Development. Myers, C. & Jones, T.B. (1993). Promoting active learning: Strategies for the college classroom. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Nunn, C. E. (1996). Discussion in the college classroom: Triangulating observational and survey results. Journal of Higher Education, 67, 243-266. Schwartz, R. M. (1994). The Skilled Facilitator. San Francisco: Jossey Bass. Sikorski, J. F., & Keeley, J. W. (2003). Teaching to influence. Psychology Teacher Network, 13, 2-4. 21 Svinicki, M. & McKeachie, W.J. (2011). McKeachie’s teaching tips: Strategies, research, and theory for college and university teachers (13th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth