DEFENCE - Australian Defence Force Journal

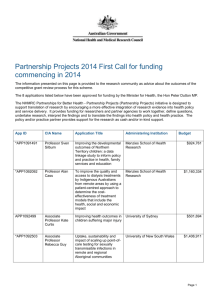

advertisement