The Integration of Existing Building Apertures for Daylighting and

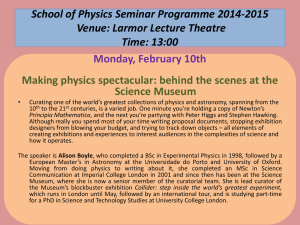

advertisement

The Integration of Existing Building Apertures for Daylighting and View in Exhibition Environments. A Master Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Sustainable Interior Environments at the School of Graduate Studies, Fashion Institute of Technology in Partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Sustainable Interior Environments By Lawrence Langham May 2013 Mentor: Barbara Campagna SUNY Fashion Institute of Technology This is to certify that the undersigned approve the thesis submitted by Lawrence Langham In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Sustainable Interior Environments _________________________________________________________________________ Grazyna Pilatowicz, Chairperson _________________________________________________________________________ Barbara Campagna, Mentor: _________________________________________________________________________ Mary Davis, Dean, School of Graduate Studies Abstract Daylight presents challenges as a source of illumination for exhibitions, notably because of the damaging effects that UV radiation and high light levels can have on collections materials. Daylight’s ephemeral quality means that it is much more difficult to control and predict in the ways that artificial light can be. Additionally, there are also concerns regarding human comfort in terms of glare and heat gain during periods of direct sunlight. Yet daylight can be highly beneficial, bringing potential environmental, economic, and health benefits, in addition to an array of interpretive, aesthetic, and programmatic possibilities. These qualities make daylighting a crucial dimension in the development of sustainable strategies for interior environments. This thesis examines the challenges and benefits of daylighting in order to look at how daylight apertures in exhibitions may benefit visitors, and offer opportunities to make connections between the experiences presented in the exhibition and the broader context of the exterior environment. Existing literature from several interrelated disciplines was reviewed in the process of preparing this thesis. Professionals were interviewed, and museum site visits were conducted. A project was identified as a case study. Research, site analysis, preliminary view and daylight analysis were conducted. A matrix of design options was compiled, tailored to the case study scope of project. The results indicate the importance of integrating daylighting expertise in the design process and how careful consideration of view can enrich the visitor experience. iii Acknowledgments “Friends are like windows through which you see out into the world and back into yourself... If you don’t have friends you see much less than you otherwise might.” -Merle Shain I am deeply grateful for the expertise, kindness, and patience of Grazyna Pilatowicz my thesis instructor whose guidance has made this thesis possible. Through Professor Pilatowicz I have had the great fortune to work with my mentor, Barbara Campagna, who brought insight and depth from her background in historic preservation. Thanks very much to both of you for the time that you have spent helping me. It has been a joy to work with you. A number of FIT faculty that have been very helpful in this endeavor. Special thanks to Cathy Bobenhausen, Donna David, Peter Johnston, Susan Kaplan and Francine Martini. Your suggestions and encouragement have been greatly appreciated. The Sustainable Interior Environments program is a new adventure at FIT, and I have been blessed to be part of a wonderful class. I would like to thank Alina Ana Coca; Christine Hyuang Kwon; Shannon Leddy; Olesya Lyusaya; Jessica News; Elizabeth Vergara; Michael Wickersheimer. I am indebted to Laurel Marx for giving me the opportunity to work on the Keeper’s House project with the Friends of the Old Croton Aqueduct and to Laura Compagni for her leadership in the Interpretive Proposal and for allowing me to interview her and include her experiences in this thesis. Thanks also to Stephen Tilly and Andreas Hubener for sharing precious information and documentation about the Keeper’s House and to Karen Snider and Brianne Muscente for sharing their professional experiences. To my family: my parents; Richard and Joanne; my partner, Gabriel; my parenting partner, Kristin, and my daughter Grace. Thank you very much for helping me to see out into the world. iv Contents iiiAbstract ivAcknowledgments v Table of Contents 1 Chapter One: Introduction 1 1 2 3 5 Thesis Topic Research Questions and Methodology Limitations and Delimitations Definition of Terms Chapter Two: Analysis 5 Review of Existing Literature 10 Site Visits to Precedents 21 Case Study: Keeper’s House, Dobbs Ferry N.Y. 21 Overview and History 23 Site Analysis 29 Daylight Analysis 31 View Analysis 36 Chapter Three: Synthesis 37 40 42 45 Design Options Conclusions Notes Bibliography v 1 Introduction Thesis topic The integration of existing building apertures for daylighting and view in exhibition environments. Research questions • When designing interpretive exhibitions for existing buildings, how can designers integrate daylight apertures while balancing concerns of human comfort? • How can daylight apertures be used to make narrative connections between the content of the exhibition and the exterior environment beyond the walls of the museum? • Why is this important? • How do exhibition designers collaborate with conservators and other team members to balance conservation considerations with visitor access to museum content? • How have other designers integrated daylight with reflective exhibition components such as monitors, display cases, and graphic panels? 1 Significance Incorporating existing apertures for daylighting, view, and orientation into exhibition design in restored, rehabilitated, and adapted buildings can entail rewards in aesthetic, economic, social and ecological terms. Balancing visitor comfort, object care, theatricality, and narrative clarity presents an array of challenges for the design team. The exhibition development and design process must be addressed with careful analysis and consideration regarding the interplay among the exhibition’s communication goals, the elements of the physical environment, and the visitors. Definition of most significant terms For the purposes of this exploration the following definitions are applied: Interpretive Exhibitions: Exhibition environments that use an array of media, interactive, and immersive approaches to engage visitors in subject content. Exhibition Narrative: The story that is told in the exhibition environment. Successful exhibitions have a coherent central thematic idea that is supported by each component within the exhibition. Daylighting: The use of building apertures in combination with reflective surfaces to provide effective interior illumination using available natural light. Conservation: The preservation of tangible cultural properties, which can include collections objects, furnishings and other materials. Historic preservation: “The process of identifying, protecting, and enhancing buildings, places, and objects of historical and cultural significance.”1 Sustainability: The interconnectedness among environmental, social, and economic considerations and imperatives. Daylighting touches upon all three of these areas. 2 Methodology Review of Existing Literature Review of existing literature in overlapping areas of exhibition design, historic preservation, object conservation, daylighting and museum lighting. Interviews and Conversations This thesis has benefited from interviews and conversations with a number of design professionals. Some of these have been formal and are noted as such in this document. Others have been informal and have helped to guide the process of exploration by offering suggestions of places to visit, books to read, and other resources. The array of expertise includes: • Exhibition Designers • Architects • Lighting Designers • Graphic Designers • Educators • Content Specialists Analysis of Site Visits and Precedents • Lower East Side Tenement Museum, New York, N.Y. • Brooklyn Children’s Museum, Brooklyn, N.Y. • Lefferts Historic House, Brooklyn, N.Y. Analysis of Case Study Keeper’s House, Dobbs Ferry, N.Y. Site of proposed educational and visitor center for the Old Croton Aqueduct. Limitations This exploration is limited by the number of interviews and site visits performed within restricted time schedule. The findings will be applied to an example of one case study. 3 De-limitations It is not the intention of this exploration to arrive at a generalized model that is applicable to all exhibition projects, nor to address all issues involved in the pursuit of sustainability in exhibition design. Attitudes regarding proper professional practice evolve, so the methods that seem appropriate today may not be in the future. Materials and technology are also evolving, so that things that seem impossible today may be possible in the future. 4 2 Analysis Review of Existing Literature Exhibitions can be sensual and enlightening experiences. They can also be dull and dreary drudges, thick with words and things that leave people tired and dopey. What makes the difference? How can we distinguish those elements and qualities that contribute to successful and effective exhibitions for planners and visitors alike? Exhibition design is a multidisciplinary endeavor, and bringing daylight and view into the planning process adds its own opportunities and complexities. The literature review for this thesis encompasses a number of interrelated areas of inquiry including: -Kathleen McLean Planning for People in Museum Exhibitions p. 163 Exhibition Design Books and articles about the exhibition design process routinely stress the importance of a clear narrative, the team development process, and a visitor centered approach. This is particularly true for interpretive environments that might be encountered in history museums, science centers, natural history museums, historic sites, children’s museums, etc. The exhibitions are often envisioned as social, interactive, and participatory, with visitors involved in broad scopes of activities that engage the visitors’ interests, aptitudes, and senses. 2 • Exhibition Design • Architectural Preservation and Historic Sites • Object Conservation • Daylighting • Museum Lighting The importance of engaging visitors in experiences that support exhibition objectives is underscored, including specific practical matters such as providing seating and ensuring that labels 5 are concise, and readable 3 as well as broader best practices such as developing a clear exhibition focus and facilitating social interaction through the design of the exhibition environment. 4 “In terms of risk management trade-offs, we must make a decision that minimizes the loss of value due to poor visual access and the loss of value due to permanent damage. In terms of ethics and visual access, we must balance the rights of our own generation with the rights of all future generations.” -Stefan Michalski “Light, Ultraviolet & Infrared” Regarding daylight, it has historically been looked upon as problematic in many exhibition settings because of concerns about its potentially deleterious effects on objects and furnishings on display. Even when there are few or no objects with strict conservation limitations in an exhibition environment, there may be other reasons why projects are planned without employing or utilizing daylight. Illustrated books such as Dernie’s Exhibition Design and What is Exhibition Design by Lee Skolnick, Jan Lorenc, and Craig Berger show numerous examples of interpretive exhibitions where the controlled theatricality of artificial lighting is combined with electronic media. Daylight is often perceived to interfere with the impact of these approaches. 5 Architectural Preservation & Historic Sites House museums and other restored or rehabilitated interpretive environments are typically different in how they approach conservation and exhibition criteria as compared with purpose-built museums. The narrative scope of a house museum, historic site, or recreational site encompasses the building itself (or buildings) and may also include the surrounding environs. The building may have objects on display, but the goal of preserving the architecture may not allow for the strict climate and light controls that would be required and designed into a purpose-built gallery. 6 Period rooms in historic houses will often include a variety of objects and furnishings, which were they on view in a purpose-built gallery, might be displayed under controlled, uniform light levels. However, in the setting of an historic room with windows this may not be an option, so other strategies must be employed that can include: utilizing window shutters or shades strategically to block or filter sunlight during periods of direct exposure; locating light sensitive items away from the path of direct sun; and selective use of reproductions. 7 Other light control methods include the use of UV and solar control materials. The context is crucial for determining the appropriate approach. For example, ultraviolet-filtering film may not be the right choice for windows with old glass with many air bubbles and irregular surfaces, as difficulties may arise when the film has to be removed. 8 Decision making requires a sustained team process with conservators, lighting designers, exhibition designers, engineers, architects, curatorial and historic preservation experts coming together to develop solutions that are appropriate for the institution and project mission. 9 6 “A bioregional approach to daylighting concerns the ways that design can grow from, respond to, engage in, and benefit from the life forces of a specific region.” -Mary Gusowski Daylighting for Sustainable Design p. 3 Historic buildings are often themselves the principal object, as is the case with the Keeper’s House, the Lower East Side Tenement Museum and the Lefferts Historic House. The interpretation of historic architectural styles, that were made with local materials utilized natural light. Buildings such as the Keeper’s House with its broad eaves, operable windows, and door transoms can offer lessons in sustainable energy consumption. 10 Beyond the envelope of the building, historic houses generally have narrative connections to their sites. There can be strong cultural, historical, geographical and environmental dimensions to these connections. Daylighting Daylighting offers an array of benefits, including the potential for energy and cost savings if daylight controls are integrated into the electric lighting systems. 11 Relatedly, solar heat gain and heat loss from daylight apertures are also to be considered, so that energy is not wasted through excessive air conditioning in the summer, or heating in the winter. Strategic use of external and/or internal light shelves, 12 external shading structures, shuttering systems, and plantings, or interior window treatments, are among the many ways to plan for these considerations. 13 Also, daylight can be a dynamic design element, used in concert with materials and forms to shape the aesthetics and sequential experiences of interior space. Because of its transitory nature, daylight can bring visual and thermal movement and contrast that changes depending upon time of day, season and climate. 14 Access to daylight is significant for health and well being, providing external cues for circadian rhythms—biological cycles that govern periods of sleeping and waking up. Daylight apertures allow people within interior environments to remain engaged with these cycles. Furthermore, daylight apertures very often provide views that can relieve visual and mental fatigue by providing a place for the eyes and mind to rest in the exterior environment. 15 The connection with exterior environment is also regarded as essential for well being because of biophilia—the affinity that people have for nature. Biophilic design seeks to plan for the interrelationship of people and the outdoor setting. Studies have indicated that access to views benefits healing, productivity, social interaction, and cognitive functioning. 16 The regular cycle of light and dark that makes daylight comforting and refreshing is, along with climate and seasonal changes, what makes it highly variable as a principle source of interior 7 light. Also, conditions range widely depending upon the site and its locality. Within the United States there are cities such as Buffalo, New York, which averages 54 days of clear skies annually. This is a very different diurnal environment from Phoenix, Arizona with 211 days of clear skies or even New York City with 104. 17 Daylighting requires careful consideration of the site, including geographic location and building orientation along with the climate and seasonal patterns. 18 Changes in the exterior such as new building construction or modified landscaping or planting can alter conditions for daylighting causing shading or adding reflected light. There are challenges presented by daylighting with regard to human comfort. Direct sunlight can cause reflective glare and bright daylight can contrast uncomfortably with elements in an interior environment. 19 Potentially uncomfortable thermal conditions may also be created in areas that are in direct sunlight. Also particularly noteworthy for many museums are the potential damage to objects, finishes, materials in interior spaces due to excessive heat, visible light, and UV radiation. 20 Planning for these risks requires collaboration among exhibition designers and conservation professionals. Object Conservation It is a paradox that the light required to see many of the objects on display in museum exhibitions is damaging to those very objects. Paintings, works on paper, textiles, wood, and animal specimens are all subject to light damage. Concerns regarding daylight and object conservation are, in broad terms, two fold: light level and the presence of UV radiation in daylight. Both are damaging to many collections objects and interior finishes. Guidelines for very sensitive objects such as watercolors, drawings, and textiles set light levels at 5 to 10 foot-candles (50 to 100 lux) This is currently considered to be the maximum allowable light level for very sensitive materials, such as prints, drawings, watercolors, dyed fabrics, manuscripts, and botanical specimens. Up to 15 foot-candles (approx. 50 lux) is thought to be appropriate for oil paintings, most photographs, ivory, wood and lacquer objects. Metal, stone, glass, ceramic, and enamel objects are generally thought to be unaffected by strong light. 21 Daylighting for Museums The preponderance of writing about museum lighting, including daylighting within exhibition environments focuses on art and collections object based exhibits, as opposed to science centers, children’s museums, and interpretive centers where conservation may be a minor concern 8 or of no concern. With conservation considerations at the forefront, a wealth of examples are available for diffuse lighting approaches, particularly for top lighting, where daylight diffusing ceilings, light baffles, reflectors and other structures are used to bounce light into the space. 22 In some cases museums have chosen to embrace the dynamism of direct sunlight, allowing it to fall into the gallery and move around the space. 23 This is an appropriate choice for exhibitions of objects made of stone, metal, or other materials that are not light sensitive. In other examples, the daylight apertures provide visual continuity between the gallery environment and the exterior, providing respite, or to bring about a connection between the art on view and the natural surroundings. 24 9 Site Visits Three museums were identified to visit for analysis of the use of existing daylight apertures in exhibition environments. At the Brooklyn Children’s Museum several spaces are considered. Historic structures at Lower East Side Tenement Museum and Lefferts Historic House were also visited. Brooklyn Children’s Museum Location: 145 Brooklyn Ave, Brooklyn, NY Original Construction: 1977 by Hardy Holtzman Pfeiffer Associates Major renovation in 1996. Most recent expansion, designed by Rafael Viñoly Architects 25 was completed in 2008, doubling the museum’s space to 102,000sq ft. Founded in 1899, The Brooklyn Children’s Museum is the first of its kind and has served as a model for hundreds of children’s museums around the world. The Museum has a mission encompassing environmental science, the arts, and cultural exploration that reaches several hundred thousand visitors per year. 26 Fig. 2.1 Aerial view of Brooklyn Children’s Museum at corner of Brooklyn Ave. and St. Marks Ave. Image: Google Earth 10 Fig. 2.2 Plan view Brooklyn Children’s Museum. Drawing: Rafael Viñoly Architects Daylight and view are integral to the design of the exhibition environments in multiple areas of the museum including the following exhibition areas: 1 - Neighborhood Nature (ground floor) 2 - Greenhouse (ground floor) 3 - Totally Tots (ground floor) 4 - Collections Central (second floor) 11 Brooklyn Children’s Museum Neighborhood Nature Located in the southeast corner of the Museum’s ground floor, Neighborhood Nature is designed to engage children in Brooklyn’s local ecology. An array of exhibition activity modules include: a play community garden; a running stream and pond with “fish eye view” and animals to discover; and a tide pool to touch live horseshoe crabs and starfish. Full height glazing on both the south and east walls offer substantial daylight to the space, yet significant areas of the windows are covered, and the overall illumination deeper in the space is muted because of the low reflectance values of the finishes within the exhibition environment. Eye level views to the east are entirely blocked by graphic murals that have been placed against the windows. Views south, into greenhouse show plants growing, but are partly blocked by exhibit structures. Fig. 2.3 Murals blocking view on east wall. Photo: L. Langham Fig. 2.4 Play gardening activity connects thematically and visually with views into adjacent greenhouse. Photo: L. Langham 12 Brooklyn Children’s Museum Greenhouse Exhibit and Activity Area The Greenhouse is adjacent to Neighborhood Nature has south, east, and west exposure to daylight. The space is used both as a flexible exhibit and classroom with graphically identified live plants and insects and insects on display, and moveable tables for classes and activities. As illustrated in the accompanying images, the wired glazing filters sunlight and partially obscures the views of the surrounding environment. Fig. 2.7 Greenhouse is used for both exhibition and informal classroom and activity space. Photo: TImeout.com Fig. 2.5 LIve insect displays in terrariums. Photo: L. Langham Fig. 2.6 Plant specimens with interpretive labels. Photo: L. Langham 13 Brooklyn Children’s Museum Collections Central Created as part of a major expansion that opened in 2008, the collections area runs parallel to approximately 100 feet of glass wall that faces east onto a concrete outdoor amphitheater. This provides daylight to the space where objects are displayed in glass cases adjacent to activities where visitors reconstruct ceramic pots, create patterns with tiles, string beads, etc. This new, bright exhibition area is spacious to the point of seeming empty in comparison to the older parts of the museum. There were noticeably more visitors in the other exhibits that have greater densities of activities. The view onto the rooftop plaza looks barren with some treetops visible in the distance. Fig. 2.8 Collections Central activities area. Photo: Brooklyn Children’s Museum Fig. 2.9 View out onto rooftop plaza showing amphitheater. Photo: L. Langham Fig. 2.10 Collections display cases showing reflections from windows. Photo: L. Langham 14 In addition to the cultural artifacts in the space, there are environmentally themed interactive components directly against the windows. One of these uses an LED light to illustrate how the solar power panels on the exterior of the building are affected by clouds, pollution, or night. Fig. 2.11 Solar energy interactive located on east facing window overlooking rooftop plaza. Photo: Liberty Science Center 15 Brooklyn Children’s Museum Totally Tots In this early childhood activity, a bank of windows run the length of the entire section, providing direct views onto St. Marks Ave. It is noteworthy that the section with the clearest visual connection to the actual neighborhood is the toddler section, although there is no direct interpretation of what is outside Fig. 2.12 Daylight is a key element in The windows—and the connection they provide to the exterior—serve as a relief to the adults that accompany the children: “Unlike an early childhood classroom, an early childhood exhibition is designed for learning by both the kids and adults. It provides an opportunity for adults to watch their kids, interact with their kids (& scaffold their learning), see other kids at the next developmental stage, and watch other adults to learn new parenting skills. That’s a lot to take in. Windows help the adults sustain their attention and engagement.” 27 Fig. 2.14 Windows in Totally Tots have northern exposure and views onto St. Marks Ave. the exhibition environment. Photo: L. Langham Photo: L. Langham Fig. 2.13 Waterplay activity area. Photo: L. Langham 16 Lefferts Historic House 452 Flatbush Ave Originally constructed: around 1783 and moved to this location in 1918 28 2 Floors 5000 Square feet Lefferts Historic House is sited within Prospect Park in Brooklyn where it reaches a broad, diverse audience, including many family and school groups. The proximity to the Prospect Park Carousel and Zoo encourages young audiences. The current exhibition design was created in 2008 by James Czajka, architect with Christopher Clark, PhD, exhibition developer and consulting historian. 29 The house has a combination of furnished period rooms and hands-on activity rooms with low-tech interactive components for informal learning, centered around activities such as cooking, candle-making, and music. The evolving cultural history of Brooklyn is explored in these interior environments as well as numerous outdoor programs. 30 Fig. 2.15 Aerial view of Lefferts Historic House in Prospect Park. Photo: L. Langham Fig. 2.16 Hands-on activities with everyday objects that tell Fig. 2.17 Sample of sheep’s Photo: urbanburden.com Photo: L. Langham environmental stories. Sunlight is penetrating western facing windows. wool is revealed in interactive graphic mural. 17 According to Billy Holiday, Director of the Lefferts Historic House, the institution is looking at the past primarily through an “environmental history lens” because of its location in Prospect Park and the expectation that people have when they come to the park that they will be experiencing nature. 31 Graphic components include: large format printed graphics, backlit graphics, and painted murals. Other exhibition components include: acrylic display cases with display objects, plastic replicas of objects for visitor activities, mechanical interactive components. Double hung windows provide substantial general lighting. Additional electric light is directed at specific exhibit items. Because the exhibits are not limited to telling the history of the house and since there are programs both inside and outside the building, the windows serve as an immediate, accessible connection between the interior and exterior. Activities include gardening, ceramics, blacksmithing, and music. Fig. 2.18 Windows provide a visual connection between the environmental themes of the exhibition and the exterior environment of Prospect Park. Photo: L. Langham 18 Lower East Side Tenement Museum 97 Orchard Street, New York NY Architectural restoration by Perkins Eastman and Li-Saltzman Architects began in the early 1990’s and the first apartment opened for visitors in 1994. 32 Located at 97 Orchard Street in Manhattan The Lower East Side Tenement Museum tells an array of stories of the immigrant experience and transformation in New York. A typical living space in the building is around 325 square feet with 8-foot high ceilings. It is estimated that 7,000 people from over 20 countries lived in the building between 1863 and 1935 when the landlord stopped renting to residential tenants. 33 The typical Tenement Museum experience is a tour that takes visitors into one or more of the living spaces to examine the lives of people who lived there in a specific time period and to consider the broader social issues: politics, health, labor, etc. affecting those lives. Fig. 2.19 Second floor Baldizzi apartment. Interior windows allow borrowed light into kitchen. Photo: Lower East Side Tenement Museum Fig. 2.18 Plan of typical floor 97 Orchard St. Li-Saltzman Architects The windows in these buildings were very significant to the narrative because of code, health, light, ventilation dimensions. Health issues were a very significant narrative component. Double hung windows in front rooms and interior windows between other spaces for borrowed light. There was no electric light until the 1920’s and no gas light until the 1880’s and that the gas light was coin operated. There was minimal use of electric light in the apartment spaces. 34 19 Laura Campagni served as an educator for the tours program at the LESTM from 2005-2008. Here is her description of one of the ways that she would use the windows to engage the visitors with the site: “When I was giving tours I would bring visitors to the windows to look and think about present day immigration. The tour would end on this note; looking through the windows at Chinatown and considering how the ethnicities have changed, yet the neighborhood remains an immigrant neighborhood. I would talk about other historical migrations into the neighborhood from places like Puerto Rico and this would lead to further conversations with the visitors.” 35 Fig. 2.20 Fourth floor restored apartment. Photo shows sunlight penetration. Photo: Lower East Side Tenement Museum Although few of the objects from the original occupants are in the building, many of the rooms have wallpaper, flooring and other materials remaining. The windows have UV filtering film applied to the inside surface, serving to block damaging ultraviolet light from affecting these materials. Most objects on view in restored rooms have been acquired at flea markets and similar sources. 36 Fig. 2.21 Detail of wall paper in unrestored room. Photo: Lower East Side Tenement Museum 20 Case Study: Keeper’s House Old Croton Aqueduct Visitor and Education Center 15 Walnut St. Dobbs Ferry, NY Overview Original Construction: 1857 Original Architect: Unknown Original Use: The home of the principal superintendent of the Aqueduct, north of New York City. Owner: New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation Partnering Organization: Friends of Old Croton Aqueduct (FOCA) Landmark Status: Designated National Landmark in 1992 as part of Old Croton Aqueduct Preservation Architect: Stephen Tilly Proposed Use: Visitor and Education Center Scheduled to Open: 2015 Square Footage: 1114 sq. ft. (first floor public spaces) Principal Source of Information: FOCA Interpretive Treatment Proposal Fig. 2.22 Keeper’s House Dobbs Ferry, NY. Front of house. Photo: Friends of Old Croton 21 Historical Background Prior to 1842 New York City did not have safe, reliable water for drinking, sanitation, and fire fighting. The creation of what is now called the Old Croton Aqueduct began a transformation of New York’s water supply, with local wells replaced by the city’s first major water supply system; gravity fed and comprised of a masonry dam on the Croton River, a 40.5-mile long aqueduct, and two reservoirs in Manhattan. 37 Fig. 2.24 Croton Reservoir, Manhattan, NY. Image: New York Public Library Fig. 2.26 Old Croton Dam. Image: New York Public Library When the Aqueduct was in active service, overseers were hired to patrol and maintain sections of the system. These “keepers” were provided with housing along the section of tunnel that they maintained and secured. Six homes were built with this particular house constructed for the principal superintendent of the Aqueduct, north of New York City. Only this one stands today. 38 Fig. 2.25 Map of Old Croton Aqueduct The Keeper’s House at Dobbs Ferry is one of the remaining above-ground structures of the Croton Aqueduct—a system that transformed New York City and bound its future growth and well being to the watersheds of New York State. Map: Scribners Monthly 22 Historic and Recreational Site In 1968 New York City sold 26 miles of the aqueduct to the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. This became a park with a trail that stretches through communities along the Hudson River between Yonkers and Cortlandt. 39 Fig. 2.27 Aqueduct trail in use next to the Keeper’s House in Dobbs Ferry. Photo: Friends of the Old Croton Aqueduct Fig. 2.28 Trail map at right of Old Croton Aqueduct and has the Keeper’s House labeled as Overseer’s House. Map: Friends of the Old Croton Aqueduct 23 Historic and Recreational Site The trail that runs outside the overseer’s house is directly on top of the aqueduct. The image on top shows one of the aqueduct ventilators encountered periodically along the trail. These are marked on map on previous page. Fig. 2.29 Old Croton Aqueduct ventilator along the trail. Photo: Mark B. John Fig. 2.30 Inside the Old Croton Aqueduct. Photo: Steve Duncan 24 Historic and Recreational Site The Keeper’s House is at 15 Walnut Street in Dobbs Ferry. On the opposite side of the street is a maintenance barn for the Park. Fig. 2.33 Sign at the edge of the Fig. 2.32 Maintenance barn for the park is to the right in this photo. trail on opposite side of Walnut street from the Keeper’s House. Photo: L. Langham Photo: Friends of Old Croton Aqueduct Fig. 2.31 Aerial view showing Keepers House to the right of trail below Walnut Street. Photo: Google Earth 25 Building Restoration/Interior Rehabilitation The Friends of the Old Croton Aqueduct are restoring the house and designing a Visitor Center that will feature an exhibition of the history of New York’s world- renowned water supply system. FOCA, in partnership with the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation, has raised $1.2 million for the restoration of the building. 40 Fig. 2.34 Plaster cieling medalian. Photo: Laurel Marx Fig. 2.35 Southeast corner of Fig. 2.36 North facing window Photo: Laurel Marx Photo: Laurel Marx house. in room 104. The interior of the building will be a rehabilitation project with restoration of many features such as plaster walls and details in exhibit areas and cast iron radiators refurbished or replaced as needed. Modifications will include an ADA accessible restroom and entrance and interior magnetic storm windows. 41 26 Architectural Shading Structures There are several significant historic structural elements of the building that provide or have provided shading. Eaves Fig. 2.36 (at right) Detail showing eaves. Photo: FOCA Fig. 2.37 (far right) Exterior shutters. Photo: FOCA Fig. 2.38 (below) Front porch. Photo: Navema Italianate style wide overhanging eaves partially shade second story windows, particularly at or near solar noon. Shutters Operable shutters would have shaded the interior spaces of the house with a significant cooling effect. Shutters and drapery would also have protected furniture, rugs, and other items from sun damage. Remnants of the old shutters are presently inside the building. Note the shadow of the shutters where the paint is missing on the outside of the building. Front Porch The porch provides shelter and serves as a transitional space at the entrance to the house. Since the front entrance primarily faces north, direct solar admission penetration through these windows is less of a concern than in other parts of the house. The porch does limit daylight penetration into interior spaces.. 27 Keeper’s House First Floor Public Spaces Room 100: Porch 140 sq. ft. Room 101: Entrance 126 sq. ft. Room 102: Restroom 48 sq. ft Room 103: Exhibition Space 257 sq. ft. Room 104: Exhibition Space 261 sq. ft. Room 105: Public Space 202 sq. ft. Room 106: Office 100 sq. ft. Fig. 2.39 Plan of first floor. Stephen Tilly, Architect 28 Daylight Analysis Room 104 West Facing Window S1 The two other windows in this room face north. These serve as sources of daylight without allowing direct sun. Room 104 Plan March 21 5:00 PM S1 Section March 21 5:00 PM S1 1'-3" 1'-3" Direct sunlight penetrates one window on the west wall in room 104. Graphic at right shows positioning at 5:00 on the approximate dates for Spring Equinox, Summer Solstice, Fall Equinox, and Winter Solstice. Room 104 Plan June 21 5:00 PM S1 Section June 21 5:00 PM S1 Room 103 5'-11" Room 104 Plan Sept 21 5:00 PM Room 104 S1 Section Sept 21 5:00 PM 15° S1 Porch Room 104 Fig. 2.40 Diagram of sun penetration room 104. Diagram by L. Langham based on house drawings by Stephen Tilley Architect Plan Dec 21 5:00 PM S1 Section Dec 21 5:00 PM 29 Daylight Analysis Room 103 South Facing Window S2 Room 103 has windows on the south and west walls. The second window in the room, on the west wall, has sunlight penetration comparable to the example illustrated in the previous page. Plan March 21 3:00 PM S2 Section March 21 3:00 PM S2 1'-3" 1'-3" The graphic at right shows positioning at 3:00 on the approximate dates for Spring Equinox, Summer Solstice, Fall Equinox, and Winter Solstice. Plan June 21 3:00 PM S2 Section June 21 3:00 PM S2 Room 103 5'-11" Room 104 Plan Sept 21 3:00 PM 15° S2 Section Sept 21 3:00 PM S2 Porch Fig. 2.41 Diagram of sun penetration room 103. Diagram by L. Langham based on house drawings by Stephen Tilley Architect Plan Dec 21 3:00 PM S2 Section Dec 21 3:00 PM 30 View Analysis A view analysis was undertaken on March 10, 2013 at the site of case study to see what visitors would see through the windows of the building. Because most of the windows were boarded up at the time of the study, the photographs were taken from the outside with the camera facing away from the windows. Fig. 2.40 Aerial view of Keeper’s House and trail with graphic overlay to suggest views from daylight apertures. Photo: Google Earth 31 Views Looking North • Include Old Croton Aqueduct Historic Trail • Orientation is highly significant as it directs visitors toward: - Croton Watershed - Sites of Old Croton Reservoir, Dam, and Gatehouses - New Croton Reservoir, Dam, and Gatehouse • Large spruce tree will be removed from center of lawn • Mobile structure on opposite side of Walnut Street will be removed to make room for parking for interpretive center. • First floor apertures facing north are two windows in the front exhibition space (room 104) and the front door, as well as a second door in room 105. Fig. 2.41 Large spruce tree in front of Keeper’s House. Photo: L. Langham Fig. 2.42 View looking north toward Croton Dam. Photo: L. Langham 32 Views Looking West • Include Old Croton Aqueduct Historic Trail • Closest view of trail and aqueduct from inside house • Perhaps best opportunity to explain that aqueduct is under trail • Include Hudson River • First floor apertures facing west are windows, one each in rooms 103, 104, and 105. Fig. 2.44 View from west side of the house. Fig. 2.45 View from west side of the Photo: L. Langham Photo: L. Langham Hudson River is seen in background. house overlooking trail. Fig. 2.43 View from west side of house with- trail visible. Photo: L. Langham 33 Views Looking South • Include Old Croton Aqueduct Historic Trail • Orientation is highly significant as it directs visitors toward New York City, the destination of Croton water. Fig. 2.47 (above)View south Fig. 2.46 (at right)View to the toward New York City. east of Keeper’s House. Photo: L. Langham Photo: L. Langham Views Looking East • Show neighborhood environment and general site. • First floor apertures facing east are three windows, one in room 102 and two in room 105. • Room 102 will be a bathroom with frosted glass window. 34 Summary for Case Study Implications for Exhibition Design at the Keepers House in Dobbs Ferry In the two exhibition rooms of the Keeper’s House there are a total of five windows, two of which have northern exposure and thus no direct sun penetration. Two of the other three windows have western exposure and one has southern exposure. The preliminary daylight analysis carried out for this thesis showed the reach of sunlight in plan and section across the rooms at specific moments in the year. This will help to begin the process of thinking about potential strategies for controlling the light while still allowing for view. As the exhibition design is developed, daylight modeling should be part of the process, including information regarding the surrounding landscape. The exhibition design will be informed by the daylight analysis and the controls by the exhibition design. The controls might take the form of movable exhibit panels, translucent graphics, sheer draperies, solar shades, or other materials listed in the matrix of design options. Flexibility is essential for changing exhibition spaces and advisable for long-term installations so that adaptations can be made as patterns of behavior, unforeseen challenges or opportunities emerge. Regarding view, visitors will be able to look out the north facing windows and see the Old Croton Aqueduct Historic Trail stretching toward the Croton Reservoir. They will be able to see through the west windows directly onto the trail and aqueduct that run parallel to the house. They will also be able to look through the south windows toward New York City where Croton water was destined. These views combine to give an orienting and environmental context for the aqueduct that is underneath the trail. Enabling visitors to fully visualize the buried aqueduct will be one of the challenges of the exhibition design for the visitor and education center. Because the exhibition will be indoors and the trail is outdoors, the views provided windows can help people to make these connections. The Keeper’s House is one of the few remaining above ground structures from the Old Croton system, and the windows have been facing out onto the aqueduct for over 150 years. As parts of the historic structure of the house, the windows have a very special role to play in framing the visitor experience. 35 3 Synthesis The analysis from precedent site visits, combined with the literature review, and interactions with design professionals were used to create a table of design challenges and options for daylighting in exhibitions. This is shown on the next pages, and while tailored for the Keeper’s House project, is intended as an approach that could be useful for other projects. Written conclusions follow, summarizing the benefits of working with daylight and view to enrich exhibition environments and how daylight and view can function as elements of an organizational strategy for sustainability. 36 Design Challenges and Options Design Challenge Example Image Object Display Reflected glare from daylight aperture on acrylic exhibition case. Options Sources Notes • Specify anti-reflective acrylic or glass. • Design space using exhibition panels as light baffles to disperse light. • Position cases out of direct light. • Optimum acrylic product factsheet: www.truvue.com/ files/file/Factsheet.pdf • Cost of anti-reflective acrylic or glass is considerably greater than standard materials. Image: Museum of Fine Arts Houston Object Display & Conservation Ultraviolet (UV) light from daylight apertures can damage collections/display objects. Image: Royal Albert Museum • Liftable fabric covers on displays in lighted areas. • Rotating items on exhibit. • Shutter windows when museum is closed. • Shade windows as appropriate with curtains, blinds, or shades. • UV filtering acrylic on cases. • UV film on glazing. • Create replicas for display and/or demonstration. • Acrylic, polycarbonate, or polyester plastic panels that include UV protection • Canadian Conservation Institute • National Park Service www.nps.gov/hfc/pdf/ex/exfab-specs-2001.pdf • Anti-reflective clear materials are coated with films that may be subject to scratching. • USDA Forest Service Exhibit Accessibility Checklist www.recpro.org/assets/.../ usfs_exhibit_accessibility_ checklist.pdf • Film specification depends upon items on display. • Film may not be appropriate for very old glass. This is critical in historic buildings. • Film must be replaced after “An Overview of Light and approximately five years. Lighting in Historic Structures • Aged UV film can peel, crack, That House Collections” and shrink. Paul Himmelstein and Barbara • UV protection can also be integrated into interior or Appelbaum APT Bulletin, Vol. 31, No. 1, Lighting Historic exterior storm windows House Museums (2000), pp. 13-15 Springer, S. (2008, May). UV and Light Filtering Window Films. Western Association of Art Conservation (WAAC) Newsletter, 30 (1), 16-23. 37 Design Challenges and Options (continued) Design Challenge Example Image Options Sources Notes Image: Mike Wiltshire National Park Service • Using fabric covers on display cases positioned in lighted areas. • Rotating items on exhibit. • Shutter windows when museum is closed. • Shade windows as appropriate using curtains, blinds, etc. • UV and visible light blocking Films. Controlling Daylight in Historic Structures: A Focus on Interior Methods” Meg Loew Craft and M. Nicole Miller APT Bulletin, Vol. 31, No. 1, Lighting Historic House Museums (2000), pp. 53-59Published by: Association for Preservation Technology International (APT) • Combine daylight strategies with electric light strategies. • Routine use of shutters and/ or shades requires institutional and staff commitment and follow through. • Use of window coverings must be weighed against impact on visitor access to daylight and view. • Specify anti-reflective acrylic • Design space using exhibition panels as light baffles to disperse light. • Position displays at right angles to direction of light. • NMC (New Media Consortium) http://www.nmc.org/ • InfoComm http://www.infocommshow. org/ Object Display & Conservation Visible light from daylight apertures can damage collections/display objects. Electronic Media • Design space using exhibition components as light Projection: Daylight in baffles to disperse light. exhibition environment may • Test projectors in exhibition wash out projected images. space prior to final installation. • Specify projector with Image: projectiondesign.com adequate lumens for light conditions, size of screen and London Transport Museum throw distance. Electronic Media Reflected glare from daylight aperture on display monitor. • Museum of the Moving Image • American Museum of Natural History • New York Historical Society • Collaborate with media professionals early in design process. Image: Leuico 38 Design Challenges and Options (continued) Design Challenge Example Image Environmental Graphics Sunlight can fade exhibition graphics due to UV and light levels. Options Sources Notes • Work closely with vendors to identify options that resist fading. • SEGD Society for Environmental Graphic Design • Graphics that are integrated into windows are an exciting opportunity. Fading, cracking, peeling, and shrinking can occur. • Specify light colored materials and finishes that minimize contrast. • Position exhibition panels (or other elements) to baffle and disperse light. • “Working with Daylight in the Museum Environment” WAAC Newsletter Volume 30 Number 1 January 2008 • International Sign Association Image: L. Langham, Building 92 Brooklyn Navy Yard Visitor Comfort Disabling or uncomfortable contrast (glare) from daylight apertures. Image: Delphi Archaeological Museum • Avoid direct sunlight onto graphic surfaces. • Use shades or blinds to soften contrast? • Specify light colored materials and finishes to minimize contrast. Visitor Comfort Reflected glare on exhibition graphics can interfere with readability of text and cause discomfort Image: L. Langham, Building 92 Brooklyn Navy Yard 39 Conclusions The glimpse of the world beyond afforded by the window view can quickly transport one elsewhere in mind if not in body. It need not take long for the mind to wander to distant places and thoughts.(Kaplan p511) Exhibitions Transport People Although exhibitions invite visitors into museum environments, the content of many exhibitions is also intended to transport visitors intellectually, emotionally and experientially beyond the defined physical walls of the buildings. In the case of the Old Croton Aqueduct Visitor and Education Center, the intention of the proposed exhibits will be to illustrate and provide multisensory experiences that assure lasting understanding of the Croton watershed and water supply system in an historical and environmental context. Daylight, sunlight, and views are available as aspects of the environment that can be utilized to illuminate and give added dimension to exhibition content. For example, visitors standing in the exhibition space looking at a visual presentation about the aqueduct that is under the trail outside the Keeper’s House can directed through graphics on and around the window to look out at the trail and visualize the enormous aqueduct that was buried there more than 150 years ago. This is the role and the power that exhibitions have as story telling environments. In order to succeed a good exhibition requires a strong multi-disciplinary team that coalesces around a clear defined narrative­—a story—that is identified at the beginning of the project. Daylight, View, and the Integrated Team Depending upon the specific needs of the project, integration of daylight and view into the design and exhibition story line necessitates agreement among team members such as lighting designers, exhibition designers, conservators, educators, curators, historic preservation professionals, architects, engineers, media consultants, and any other collaborators identified as appropriate for the particular project’s needs. These professionals can offer multiple perspectives on the myriad challenges, options, opportunities, and nuances of working with daylight and view. Individually each can offer specific expertise. Together they can create a project with transportive power. Daylight Decisions Depend Upon Context, Analysis, and Planning Design criteria vary widely from one institution and project to another, and the choices made by exhibition development teams with regard to daylighting and view will logically follow the 40 general criteria for the project. Because of the transitory nature of daylight, particularly careful analysis and planning is essential. Wherever possible, testing strategies on site is an excellent practice. Daylight modeling is also an option. Institutional Commitment and Sustainability Daylighting should be a crucial component of any institutional sustainability strategy, by virtue of its potential environmental, economic, and aesthetic advantages along with the physical, psychological, and health and benefits that daylight brings to people. As the Keeper’s House demonstrates, existing buildings can offer lessons from the past about how to manage and utilize daylight. Daylight apertures also serve to connect the institution’s interior environment with its site and to the broader natural and cultural environment. The windows of the house also offer views onto the trail and aqueduct that connect the house to other components of the historic Croton system. The Friends of the Old Croton Aqueduct are committed to the preservation of the Keeper’s House as an educational and visitor center. This is in essence a commitment to sustainability in several respects, as it seeks to preserve an historic site, to offer informal learning regarding history and water use, and to create a new public institution within its community. 41 Notes National Trust for Historic Preservation. “What is Historic Preservation?” Preservation Nation, n.d. Web. 14 Apr. 2013. <http://www.preservationnation.org/resources/faq/careersand-/what-is-historic.html>. 1 McLean, Kathleen. Planning for People in Museum Exhibitions. (Washington D.C.: Association of Science and Technology Centers, 1993) 12-14. 2 Smithsonian Accessibility Program, “Smithsonian Guidelines for Accessible Exhibition Design” n.d. Web. 6 Mar, 2013 <www.si.edu/opa/accessibility/exdesign>. 3 4 5 McLean, 5. McLean, 146. Craft, Meg Loew, and Nicole Miller. “Controlling daylight in historic structures: a focus on interior methods.” APT bulletin 31.1 (2000): 53-57. Web. 15 December 2012 <http://www. jstor.org/stable/1504727>. 53 6 Fisher, Charles and Ron Sheetz “Reducing Visible and Ultraviolet Light Damage to Interior Wood. Finishes” Preservation Tech Notes, National Park Service 1990 Web. 6 Mar, 2013. <www.nps.gov/tps/how-to-preserve/tech.../Tech-Notes-Museum02.pdf> 7 8 Craft and Miller, 55. Himmelstein, Paul, and Barbara Appelbaum. “An Overview of Light and Lighting in Historic Structures That House Collections.” APT bulletin 31.1 (2000) 15 9 United States National Park Service. Guiding Principles of Sustainable Design, Denver CO: National Park Service, 1993. 10 11 2000. 79. Guzowski, Mary. Daylighting for Sustainable Design. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 42 12 13 14 Cuttle, Christopher Light for Art’s Sake Oxford, UK: Butterworth-Heinemann, 2007. Guzowski, 94. Guzowski, 3-15. Kaplan, Rachel. “The Nature of the View from Home Psychological Benefits.” Environment and Behavior 33.4 (2001): 511 15 Heerwagen, Judith, and Betty Hase. “Building biophilia: Connecting people to nature in building design.” Environmental Design and Construction. March/April issue Web. (2001). 2-4. 16 National Climatic Data Center “Cloudiness - Mean Number of Days” 20 Aug. 2008, 4 Apr 2013 <http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/oa/climate/online/ccd/cldy.html>. 17 18 19 Guzowski, 62. Cuttle, 263-280. Michalski, Stefan. “Light, ultraviolet and infrared.” Canadian Conservation Institute, http://www. cci-icc. gc. ca/crc/articles/mcpm/chap08-eng. aspx (2010). 20 McCormick, Mickie. “Measuring Light Levels for Works on Display” The Exhibition Alliance Technical Note, 2001. 21 22 23 24 Cuttle, 79-91. Cuttle, 62. Cuttle, 117. “Brooklyn Children’s Museum History” Brooklyn Children’s Museum, n.d. Web. 18 Mar. 2013 <http://www.brooklynkids.org/index.php/whoweare/history>. 25 26 27 28 Ibid. Snider, Karen “Thesis” Email to Lawrence Langham. April 29, 2013. “Lefferts Historic House” Prospect Park Alliance, 20 Apr. 2013 <http://www.prospect43 park.org/about/history/historic_places/h_lefferts>. 29 30 31 Ibid. Ibid. The History Channel “Lefferts Historic House” Online video clip. Youtube 9 Dec, 2008. Dolkart, Andrew S. Biography of a Tenement House in New York City: An Architectural History of 97 Orchard Street. Vol. 7. Center for American Places Incorporated, 2007. Print. 117121 32 33 34 35 Dolkart, 19. Dolkart, 81-85. Compagni-Sabella, Laura. Telephone interview. 11 Jan. 2013. Tutela, Joelle Jennifer. Becoming American: A Case Study of the Lower East Side Tenement Museum. ProQuest, 2008. 119. 36 Compagni-Sabella, Laura and Laurel Marx “Interpretive Treatment Proposal: Old Croton Aqueduct Visitor and Education Center” (Proposal for Friends of Old Croton Aqueduct) 9 Sept 2012., 2. 37 Friends of the Old Croton Aqueduct “The Keepers House” n.d. Web. 7 Mar 2013. <http://www.aqueduct.org/keepers-house>. 38 39 40 Compagni-Sabella and Marx, 5. Compagni-Sabella and Marx, 5. Hubener, Andreas “Some questions regarding Keeper’s House” Email to Lawrence Langham. 27 November 2012. 41 44 Bibliography Compagni-Sabella, Laura and Laurel Marx “Interpretive Treatment Proposal: Old Croton Aque- duct Visitor and Education Center” (Proposal for Friends of Old Croton Aqueduct) 9 Sept 2012. Craft, Meg Loew, and Nicole Miller. “Controlling daylight in historic structures: a focus on inte rior methods.” APT bulletin 31.1 (2000): 53-57. Web. 15 December 2012 <http://www. jstor.org/stable/1504727>. Cuttle, Christopher. Light for Art’s Sake Oxford, UK: Butterworth-Heinemann, 2007. Print. Dernie, David. Exhibition design. New York: W. W. Norton, 2006. Print. Dolkart, Andrew S. Biography of a Tenement House in New York City: An Architectural History of 97 Orchard Street. Vol. 7. Center for American Places Incorporated, 2007. Print. Guzowski, Mary. Daylighting for Sustainable Design. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 2000. Print. Hefferan, Steven “Working with Daylight in the Museum Environment” WAAC Newsletter Vol ume 30 Number 1 January 2008. Web. 12 December 2012 <cool.conservation-us.org/ waac/wn/wn30/wn30-1/wn30-107.pdf> Himmelstein, Paul, and Barbara Appelbaum. “An Overview of Light and Lighting in Historic Structures That House Collections.” APT bulletin 31.1 (2000): 13-15. Koeppel, Gerard T. Water for Gotham: A history. Princeton University Press, 2000. Print. Lorenc, Jan, Lee Skolnick, and Craig Berger. What is exhibition design?. RotoVision, 2007. Print. McCormick, Mickie. “Measuring Light Levels for Works on Display” The Exhibition Alliance Technical Note Hamilton NY 2001. Web. 2 March 2013. Michalski, Stefan. “Light, ultraviolet and infrared.” Canadian Conservation Institute, 2010. Web. 25 Feb 2013 <http://www. cci-icc. gc. ca/crc/articles/mcpm/chap08-eng. aspx> 45 McLean, Kathleen. Planning for People in Museum Exhibitions. Washington D.C.: Association of Science and Technology Centers, 1993. Print. Park, Sharon C. “Sustainable Design and Historic Preservation.” CRM-WASHINGTON- 21 (1998): 13-16. Web. 26 March 2013. <smartplaces.com>. Smithsonian Guidelines for Accessible Exhibition Design Smithsonian Accessibility Program. Smithsonian guidelines for accessible exhibition design. Mar. 6, 2008. Web. 9 March 2013 <www.si.edu/opa/accessibility/exdesign>. Taylor, Thomas H. Jr. “Lighting Historic House Museums” APT Bulletin, Vol. 31, No. 1, Light ing Historic House Museums (2000), p. 7 (APT) Web. 15 Dec. 2012 <http://www.jstor. org/stable/1504716> Tutela, Joelle Jennifer. Becoming American: A Case Study of the Lower East Side Tenement Museum. ProQuest, Ann Arbor MI 2008. United States National Park Service. Guiding Principles of Sustainable Design, Denver CO: Na tional Park Service, 1993. Print. © 2013 Lawrence Edward Langham 46