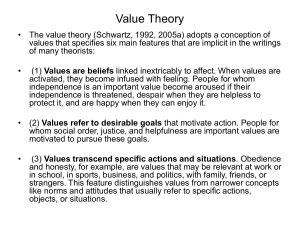

Refining Basic Individual Values Theory: Schwartz

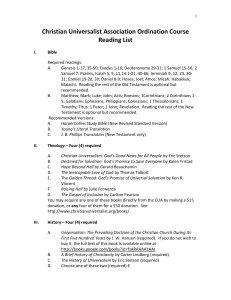

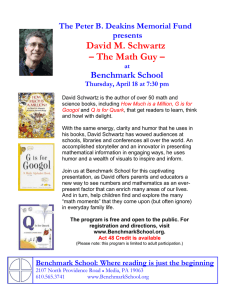

advertisement