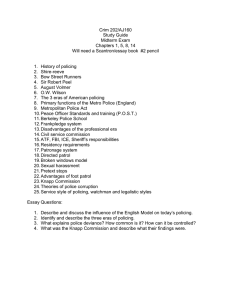

13 Identifying and Defining Policing Problems

advertisement