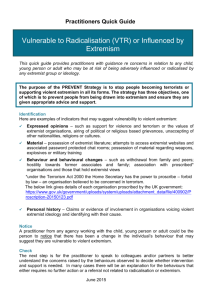

De-Radicalising Islamists: Programmes and their Impact in

advertisement