2005 > HOT TOPICS 51

TOPICS

HOT

L E G A L

I S S U E S

I N

P L A I N

L A N G U A G E

This is the fifty-first in the series Hot Topics: legal issues

in plain language, published by the Legal Information

Access Centre (LIAC). Hot Topics aims to give an

accessible introduction to an area of law that is the

subject of change or public debate.

AUTHOR: Stella Tarakson

EDITOR: Cathy Hammer

DESIGN: Bodoni Studio

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: The publisher would like

to thank the NSW Parliamentary Research Service for

permission to draw on Briefing Papers 7/2002 and

11/2002 on Public Liability by Roza Lozusic to

produce this Hot Topics issue; also to the the Australian

Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) for

permission to use the graph on p 3.

Personal injury

1

Overview

2

The law of negligence

3

Public liability insurance

5

The public liability crisis

Dispute as to the causes – contributing factors – responses to the crisis

– arguments for and against the need for reform

9

Changes to the law in New South Wales

Stage 1 reforms – stage 2 reforms – recent legislation on personal injury

15

Sporting bodies

The law before the reforms – waivers and warnings – what the

law is now

17

State Library of NSW

Cataloguing-in-publication data

Hot Topics, ISSN 1322-4301, No. 51

1. Insurance, Liability – Law and legislation – Australia.

2. Insurance, Liability – Law and legislation – New South

Wales.

3. Personal injuries – Australia.

4. Personal injuries – New South Wales.

I. Tarakson, Stella.

II. Hammer, Cathy.

III. Legal Information Access Centre. (Series: Hot topics

(Sydney, N.S.W.) ; no. 51)

346.940865

346.9440865

© Library Council of New South Wales 2005. All rights

reserved. Copyright in Hot Topics is owned by the Library

Council of New South Wales (the governing body of the State

Library of New South Wales). Apart from any use permitted

by the Copyright Act (including fair dealing for research or

study) this publication may not be reproduced without written

permission from the Legal Information Access Centre.

Public authorities

Wide exposure – changes to the law – cases on councils’ duty of care

20

Medical negligence

The law before the reforms – arguments for and against reform –

new laws

22

Conclusion: Are the reforms working?

The impact on insurance premiums – have the reforms gone too far?

24

Contacts and further reading

Hot Topics is intended as an introductory guide only

and should not be interpreted as legal advice. Whilst

the Legal Information Access Centre attempts to

provide up-to-date and accurate information, it makes

no warranty or representation about the accuracy or

currency of the information it provides and excludes, to

the maximum extent permitted by law, any liability

which may arise as a result of the use of this

information. If you are looking for more information on

an area of the law, the Legal Information Access Centre

can help – see back cover for contact details. If you

want legal advice, you will need to consult a lawyer.

view

Over

It was like a balloon that kept inflating. Claims

and compensation payouts were getting bigger

and bigger. Insurance premiums kept rising.

Public liability insurance became harder to

obtain. Many community events were cancelled

and many small businesses (such as adventure

tourism operators) were unable to carry on.

Everyone knew the balloon would burst. But

how? And what would happen next?

This issue of Hot Topics looks at personal injury law,

negligence, and the unprecedented reforms that have

been driven by the public liability crisis. It looks at the

causes of and responses to the crisis, before examining the

legal reforms that took place in New South Wales. It then

goes on to consider the major players in more detail:

sporting bodies, p 15; public authorities (including local

government), p 17; and medical practitioners, p 20.

In recent years, Australia has struggled through a situation

popularly tagged as a ‘public liability crisis’. There are

competing views as to why insurance premiums grew so

fast: see p 5 the Public Liability Crisis. Whatever the

reasons, the hike in premiums resulted in many groups

limiting or not offering certain activities and events. Most

notably, many community-run events such as street fairs,

country shows, and sporting activities were discontinued.

The information in this issue is limited to personal

injuries arising from public and product liability, sporting

accidents and medical negligence. Information on injuries

that arise out of or in the course of employment, which

are dealt with under workers’ compensation law, is

available in The Law Handbook, Chapter 24

‘Employment’ 9th ed. 2004 Redfern Legal Centre

Publishing. Information on motor vehicle accidents is

covered on pages 72-88 of The Law Handbook. This book

is available in all public libraries in NSW.

This perceived crisis prompted reforms by governments

to the law of negligence and restrictions on people’s right

to sue. Recently, senior members of the judiciary have

spoken out about the possibility that reforms have gone

too far1:

For all these issues to make sense, we first need to examine

the law of negligence. What is a negligent action and

when does it give rise to legal liability?

We have to be careful that we do not reject just

claims and unfairly reduce the mutual sharing of

risks when things go seriously wrong.

High Court Judge, Michael Kirby

Those who act negligently are partially relieved of

the consequences of their default, as is their

insurer, to the detriment of the victim of

negligence and possibly the broader community

Chief Justice of the Queensland Supreme Court,

Paul de Jersey

image unavailable

1. ‘Judge joins attack on insurers over personal injury’ by Michael Pelly, Sydney Morning Herald, 23 March 2005.

Overview

1

The

law

of negligence

Negligence comes under a large body of law

called ‘torts’. Torts are wrongdoings that give

injured individuals or organisations the right to

sue other individuals or organisations on their

own behalf. (Note: organisations include

businesses.)

Torts can be compared to crimes, where it is the Crown

who takes legal action on behalf of the community. In

other words, a tort is a type of ‘civil’ wrong as opposed to

a criminal wrong. Other types of civil law matters include

contract disputes and family law.

Tort law evolved over a long period of time as part of the

common law of England, which we inherited. Common

law is judge-made law, as opposed to legislation or statutes,

which are created by parliament. Statutes cannot cover

every single aspect of the law, of course, and even where

they do exist, courts still have to interpret them. It is these

decisions that shape the ever-changing common law.

Courts can only make decisions on cases that are brought

to them. Parliament does not face such restrictions, and is

able to create statutes within the powers defined for it by

the Constitution. Legislation passed by parliament over­

rides the common law to the extent that the two are

inconsistent.

There are various kinds of torts. Defamation, trespass and

nuisance are torts, but the most common is negligence.

Broadly speaking, negligence involves carelessness, or a

image unavailable

2. This is a UK case that is not freely available on the internet.

2

HOT TOPICS 51 > Personal injury

failure to take reasonable care

for other people’s safety. An

individual or organisation can be

sued for their negligent acts or

omissions that result in injury,

death or property damage.

For negligence to be established,

the plaintiff (the person bring­

ing the action), must be able to

prove each of three things:

> there was a duty of care – that

is, there was an obligation on

behalf of the defendant to

take reasonable care to pre­

vent injury arising from their

act or omission

> this duty was breached – not

only did the duty of care exist,

there must have been an

actual failure to use reason­

able care

> this breach caused the injury

– the injury was due to the

breach of the duty of care, not

to some intervening factor.

HOT TIP

In the past, it was difficult

to establish a duty of care

in the absence of a

contractual relationship.

But the landmark case

Donoghue v Stevenson

[1932] AC 562, extended

the duty to anyone who can

‘reasonably be foreseen’ as

likely to be injured by an

act or omission. In that

case, a woman who fell ill

and suffered shock after

drinking a bottle of ginger

beer with a decomposing

snail in it was able to sue

the manufacturer, even

though she had not bought

the drink herself (that is,

she had no contract with

either the manufacturer or

the retailer). Available at

www.scottishlawreports.org

.uk Select ‘Key Scottish

cases’ and then ‘Donoghue

v Stevenson’.

So, the question that arises is – was the risk of injury or

damage ‘reasonably foreseeable’? This test rules out

damage that is too remote, but past cases have shown that

the test can be applied narrowly or widely. Courts have

stated that the kind of damage must be foreseeable, not

necessarily the actual damage or its extent. In Hughes v

Lord Advocate 2 [1963] AC 837, workers dug a manhole in

a public street. They left the site after securing the

manhole and placing paraffin lamps around it as a

warning. Two young boys caused a paraffin lamp to fall

into the hole, resulting in an explosion. One of the boys

fell into the manhole, and suffered severe burns. The

House of Lords decided that a child being injured by

falling in the hole or being burned by a lamp was a

foreseeable risk. Although the explosion was unforseeable,

the injury fell within the kind of injury that could be

foreseen, even though the severity was unexpected.

Public liability

insurance

People who owe a duty of care generally cannot

afford to pay compensation for all the risks to

which they are exposed. To cover themselves,

they take out insurance.

Insurance transfers the possible risk of loss arising from

particular future events from a person or organisation (the

insured) to the insurer. A person who wants insurance

pays a sum of money (called a premium) to the insurer. In

return, the insurer promises to compensate the insured if

the event occurs and causes loss or damage. The event

must occur during the policy period in order to be

covered.

Both sides to an insurance contract are taking on a risk.

The insurer takes the risk that if a particular event occurs,

they will have to pay out money in compensation. But the

insured also accepts a risk. Their risk is that they will

continue to pay premiums without ever receiving any

financial benefit from doing so. If an insurance policy is

not taken out, however, the person or organisation in

question takes on the entire risk of loss.

Liability insurance covers the risk of causing personal

injury and death, as well as related loss or damage. These

policies usually require the insured to take all reasonable

precautions to prevent the liability from arising in the first

place. There are various types of liability insurance – as

well as public liability insurance, there is liability

insurance for workers’ compensation, motor vehicle third

party, product liability and professional indemnity.

Public liability insurance protects the insured from the

financial risk of being liable to a third party for death,

injury or damage to property resulting from the insured’s

negligence. The protection can relate to a location, the

use of property, or the activities of individuals or a group

of people.

Most people have public liability insurance as a

component of their home and contents insurance policy.

This is relatively minor, however, and is not the concern

of the public liability crisis. Rather, problems have arisen

with the stand-alone public liability policies that are sold

to individuals and organisations for commercial purposes.

In the late 1990s, insurance premiums for such policies

rose alarmingly for councils, community organisations,

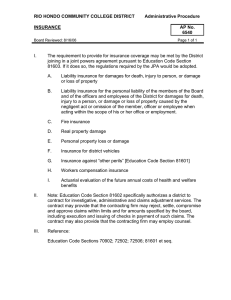

Percentage change in real average premiums –

public liability – 1998 to 2004*

The real average premiums fell by 15 per cent in the period between

year ending 31 December 2003 and half year ending 30 June 2004,

reversing the trend of substantial increases since 2000. The real

average premium decreased for most insurers.

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

0

–10%

–20%

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004*

Underwriting year ending 31 December

Notes:

*1 January to 30 June 2004

Data is shown in real terms adjusted to 30 June 2004 values using

average weekly earnings.

Derived by ACCC from responses provided by seven insurers.

sporting event organisers and adventure tour operators.

This resulted in many events being cancelled and some

businesses being forced out of operation. Even ‘not-for­

profit’ bodies were unable to afford the increased

premiums, resulting in the cancellation of various

fundraising activities.

HOW ARE PREMIUMS SET?

Premiums vary between insurers, and depend on the

particular type of risk being insured. They also depend to

a large degree on the competition faced by the insurance

companies and their relative market share. However, the

very nature of public liability insurance causes some

difficulties when it comes to setting appropriate

premiums.

Public liability insurance

3

HOT TIP

‘Long tail’ insurance

Public liability insurance is

referred to as ‘long tail’ insur­

ance. This means there can be a

large time gap between when a

policy is taken out and when the

financial outcome of a claim is

finally realised. Claims can be

made years after an accident

(depending on the statute of

limitations), even if the policy

has since expired. As a result, it

can be hard for insurers to

estimate future claims costs with any great degree of

accuracy. This makes it difficult to set suitable premiums.

A statute of limitations

provides for a limit on the

time that can elapse

before legal action is

taken. In NSW, the

Limitation Act 1969

provides for a limitation on

wide-ranging causes of

action brought about in

NSW courts, including

personal injury actions.

The Insurance Council of Australia (ICA) noted that: ‘If

a child of one year of age in NSW was injured, legal

action could be commenced some 25 years after a policy

has expired. There is no need to commence legal action

until the child achieved majority at 18 years of age when

the statute of limitations of three years applies. A further

extension of five years may also be granted.’ (Source: ICA,

Public Liability Submission to Ministerial Forum, March

2002, p 10)

Unpredictability

Public liability insurance is also characterised by

unpredictability. Some events are relatively predictable,

such as people falling over in shopping centres. Others,

however, are much harder to predict. Major accidents and

disasters can happen without warning and take

everybody, including the insurance industry, by surprise.

For example, the terrorist attacks in the United States on

11 September 2001 shocked the world. Many

commentators agree that the global repercussions of the

attacks have contributed to the Australian public liability

insurance crisis.

image unavailable

4

HOT TOPICS 51 > Personal injury

The public liability

crisis

Between 2001 and 2003 the average public

liability premium rose from just over $800 to just

under $1400 according to the Australian Com­

petition and Consumer Commission3. The reasons

for that rise, however, are not clear-cut.

Stakeholders disagree as to the main cost drivers,

placing the blame on different factors. Even where

they agree as to some common causes, they place

different emphasis on their relative weights.

> aggressive competition between insurers in the 1990s,

which led to premiums falling to unsustainable levels

> the collapse of HIH and industry mergers

> increased reinsurance costs

> changes in the international risk environment

> reduction in investment earnings

> renewed focus on profitability

> increased costs associated with prudential regulation

DISPUTE AS TO THE CAUSES

On 27 March 2002, the first of several national

ministerial meetings examining the public liability crisis

was held. At this meeting, discussions revolved around

the increase in premiums, the contributing factors for

these increases, and proposals for reform.

In their submission to the ministerial meeting, the

Insurance Council of Australia (ICA) stated that the

causes of the premium increases included:

> industry cycle of insurance profitability (which is influ­

enced by the stock market)

> taxes and levies.

So what view finally arose from the Ministerial Meeting?

A Joint Communique 4 was issued, and it found that both

sides of the argument had valid points. It held that the

premium increases were due to a combination of factors,

the most significant being:

> changing community attitudes to litigation

> an increase in the number and size of claims

> changes in what constitutes negligence

> changes in society’s attitudes regarding the making of

claims

> increased damages payouts for bodily injury claims

> changes to regulations covering lawyers, which have led

to more active pursuits of class actions

> advertising by lawyers promoting a ‘no win, no pay’

system, which encourages claims that might have not

been pursued in the past

> legal expenses involved in assessing claims

> higher risk recreational activities

> reinsurance costs

> insurance taxes.

The Australian Plaintiff Lawyers Association (APLA) –

now known as the Australian Lawyers Alliance –

disagreed. In their submission to the March 2002

Ministerial Meeting, they argued that the increases in

premiums were the result of market forces. These market

forces included:

THE HIH COLLAPSE

On 15 March 2001, the major companies in the HIH Insurance

Group (HIH) were placed in provisional liquidation. Questions

about corporate mismanagement within HIH saw the

appointment of a Royal Commission in August 2001. The

Royal Commission’s report The Failure of HIH Insurance was

publicly released on 16 April 2003 together with the

Government’s response.

The collapse of HIH is likely to be the largest corporate

failure in Australia to date. The collapse was not due to fraud

or embezzlement. The primary reason for the failure was that

adequate provision had not been made for insurance claims

and poor commercial decisions were made. The ultimate

shortfall is likely to be in the billions of dollars.

Research Note no. 32 of 2002-03

Report of the Royal Commission into HIH Insurance

BRENDAN BAILEY, Law and Bills Digest Group

Available at http://www.aph.gov.au/library/pubs/rn/

3. ACCC Public Liability and professional indemnity insurance – fourth monitoring report, 15 February 2005.

4. Available at www.lgsa.nsw.gov.au

The public liability crisis

5

CASE STUDIES

> past under-pricing and poor profitability of the insur­

ance industry

SWAIN v WAVERLEY COUNCIL

> the collapse of HIH

One such case involved a surfer who was rendered a

quadriplegic after diving into surf at Bondi Beach, striking a

sandbar. The case was heard in the Supreme Court of New

South Wales. The arguments revolved around whether

Waverley Municipal Council owed swimmers a duty of care

and the extent of that duty. The issues included whether

warning signs should have been put up, whether the risk of

diving into such waters was obvious, and whether the flags

were placed improperly. After an allowance for contributory

negligence of 25 per cent (meaning he was that much to

blame), the plaintiff obtained a judgment of $3.75 million. The

council later successfully appealed against the judgment to

the Court of Appeal: Waverley Municipal Council v Swain

[2003] NSWCA 61. Mr Swain appealed to the High Court,

which overturned the appeal decision and reinstated the

original damages award: Swain v Waverley Council [2005]

HCA 4. The cases are available at http://www.austlii.edu.au/

au/cases/nsw/NSWCA/2003/61.html (NSW Court of Appeal)

and http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/cases/cth/high_ct/

2005/4.html (High Court).

> insurance companies being more selective about the

risks they cover.

COLE v SOUTH TWEED HEADS RUGBY LEAGUE

FOOTBALL CLUB LTD

Another much-publicised case involved a woman who sued a

club because she was hit by a motor vehicle shortly after

leaving the club’s premises. She was intoxicated when she

left, with an alcohol blood level of 0.238. This case was also

heard in the Supreme Court of New South Wales. Arguments

focused on whether the club owed customers a duty to take

reasonable care to monitor and moderate the amount of

alcohol served, even when the customer voluntarily and

deliberately decided to drink to excess. Furthermore, did the

club owe a duty to take reasonable care that the customer

travelled safely away from the premises, and did the offer of

a courtesy bus/taxi satisfy this duty? The court found in

favour of the plaintiff. It apportioned responsibility as follows:

30 per cent to the driver, 30 per cent to the club, and 40 per

cent to the plaintiff herself. The injured woman was awarded

approximately $172,000 against the driver and approximately

$251,000 against the club. (Cross-claims between the club

and driver were also awarded). The defendants appealed to

the Court of Appeal, and won. The injured woman then

appealed to the High Court seeking to overturn the Court of

Appeal’s judgment, but her appeal was dismissed: Cole v

South Tweed Heads Rugby League Football Club Ltd [2004]

HCA 29. Decision available at http://www.austlii.edu.au/

au/cases/cth/high_ct/2004/29.html

HOT TIP

A cross-claim is a claim made in response to another claim –

for example, a defendant accused of causing an injury when

failing to stop at a red light might cross-complain against the

mechanic who recently repaired the car, claiming that

negligence resulted in the brakes failing and, hence, that the

accident was the mechanic’s fault. This means the matters

may be heard and decided together.

6

HOT TOPICS 51 > Personal injury

HIGH PROFILE COURT CASES

Some cases received a great deal of media attention, not

least for the large compensation payouts awarded by the

courts. Although some were later overturned on appeal,

the cases highlighted the willingness of the courts to find

that negligence existed and to award high sums in

damages. High media coverage of these cases perhaps

contributed to the changing of community attitudes

towards litigation.

CONTRIBUTING FACTORS

Insurance premiums, therefore, increased due to a

complex interaction of various factors. Some of these are

explored in more detail.

Increase in number and size of claims

Figures released by the Australian Prudential Regulation

Authority (APRA) in 2002 showed increases to costs of

claims:

1998-2000

Number of public liability claims

55,000 – 88,000

Costs of public liability premiums Up 14%

Overall cost of claims

Up 52.5%

The Australian Plaintiff Lawyers Association (APLA)

suggests it is misleading to look at claim numbers in

isolation. They say there is a proportionate relationship

between the number of claims and the numbers of

policies written, and that it is important to look at the

ratio of claims to policies. In other words, if there is an

increased number of policies written, there will be an

increase in the number of claims. Based on their own

ratio figures, they maintain that the real increase in claims

from 1996 to 2001 was only 2.63 per cent.

Changing attitudes to litigation

There is an assumption that litigation levels have boomed

in the past decade. Media reports of unprecedented large

lump sum payouts have fuelled such beliefs, even though

some of these large payouts were later reduced on appeal.

The APLA President warned against ‘… accepting

anecdote as truth and responding with unfair restrictions

on compensation, which both hurt the injured and do

nothing to solve the underlying problem of premium

increases.’ (Source: Plaintiff, Issue 49, pp 4-5)

Collapse of HIH

Civil actions commenced in Australia

The collapse of HIH in 2001 had a dual effect on

increasing premiums. First there was a reduction in the

availability of cover, and second, flow on costs resulted.

The ICA noted that HIH used to cover a large proportion

of the liability market, so its collapse resulted in a reduced

industry capacity to provide cover.

840 000

820 000

800 000

780 000

760 000

740 000

September 11

720 000

The terrorist attacks in the United States on 11

September 2001 also contributed to the increase in

insurance premiums in Australia. This is because

reinsurance costs increased. Reinsurance companies are

the insurers’ insurers – or the companies that insurance

companies go to to take out insurance cover. Global

reinsurance costs rose, putting pressure on Australian

insurance companies. This was passed to policyholders in

the form of higher premiums.

700 000

680 000

660 000

640 000

93/94

94/95

95/96

96/97

97/98

98/99

99/00

(Source: APLA, Submission to the National Ministerial Summit into

Public Liability Insurance, March 2002, p 15).

Some say that there has been a change in attitude to

litigation, a growing belief that someone had to pay. This

change in attitude may be partly due to the public being

better educated about their rights.

The APLA submission to the Ministerial Meeting

included data from the Australian Productivity

Commission, showing a slight overall decline in the level

of litigation since 1994/95, following a peak in 1996/97:

see graph. There is general agreement that there was a rise

in overall claims and in the ratio of claims to policies

written. However, the APLA did not believe that

increased claims necessarily translated to a rise in

litigation, as most personal injury claims are settled out of

court.

The advertising of conditional cost agreements is often

blamed as an exacerbating factor in an increased

willingness to commence

litigation. Also referred to as ‘no

HOT TIP

win, no pay’, lawyers can enter

Conditional cost agree­

agreements where their costs are

ments are often confused

conditional on a successful

with the contingency fee

outcome. If the case fails, the

system existing in the

client will not be charged for the

United States. Under the

American system, lawyers

lawyer’s ‘labour’. They may still

can charge a proportion of

be charged disbursements (the

the amount awarded in

lawyer’s out-of-pocket expenses

proceedings. In Australia,

such as filing fees) and court

practitioners can charge a

costs if so ordered by the court

premium on top of the

(called party/party costs). But if

legal costs otherwise

the case succeeds, the lawyer is

payable, subject to a

successful outcome. This

able to charge a higher fee than

premium is a percentage

they would otherwise. For more

of the legal costs (up to 25

information see Hot Topics 46:

per cent) – not a

You and Your Lawyer.

percentage of the final

sum awarded.

Underpricing premiums

Over the past decade, insurers have been cutting

premiums to gain a competitive edge in the market place.

So, rather than pricing premiums to reflect risk, they have

been pricing them to be competitive. The APLA claims

image unavailable

Disgraced businessman Rodney Adler leaves court for

Silverwater prison on 14 April 2005. He was sentenced to

41⁄2 years for his part in the collapse of HIH.

Nick Moir, SMH.

The public liability crisis

7

image unavailable

Amusement parks were one of the many business areas

threatened with closure due to insurance being

unaffordable or unobtainable.

that these lower levels proved to be unsustainable, and a

rise was inevitable.

The Negligence Review Panel was appointed in July

2002. The panel’s final report, The Review of the Law of

Negligence, is commonly referred to as the Ipp report. It

contained various recommendations for reform, and

created the basis for possible reform in all Australian

jurisdictions.

ARGUMENTS FOR AND AGAINST THE

NEED FOR REFORM

For information on the actual reforms, see p 9 ‘Changes

to the law in New South Wales’. But first, here are

some instances of the controversy that the reform process

itself raised.

Those pressing the need for law reform included the ICA,

medical representative bodies such as the Royal Australian

College of General Practitioners, sporting organisations

and adventure tourism operators. In its submission to the

Negligence Review Panel, the ICA stated that tort law

reform will ‘… go a long way to resolving the insurance

crisis and reducing the frequency and cost of claims. This

is expected to bring greater capacity into the market and

to stabilise or reduce premiums.’

8

HOT TOPICS 51 > Personal injury

Of course, not everyone was in favour of the proposed

reforms. One of the main concerns expressed by the Law

Council of Australia related to the amount of time the

Negligence Review Panel had to inquire into and report

on reforming negligence. The ACCC was concerned that

some of the far-reaching changes were ‘quick-fix’ reactive

solutions, without adequate attention being paid to long­

term effects.

The objections also went to the substance of the reforms

themselves. In a media release (dated 30 May 2002) the

Australian Plaintiff Lawyers Association stated that,

‘Market failure in the provision of insurance cannot be

solved by changes to tort law. Restrictions on the rights of

claimants shifts costs from insurers and defendants to

claimants and the community, but do nothing to address

the underlying market forces that drive premium

increase.’

Some commentators have pointed out that the trend in

judicial decision-making in recent years has been more

restrictive. That is, judges themselves have put a rein on

cases, lessening the need for legislative changes.

Changes to the law

in New South Wales

In New South Wales, the Government response to

the ‘public liability crisis’ (see p 5) involved

substantial change to the law through the

introduction of new legislation and amendment to

some existing legislation.

general damages and setting out maximum payouts for

loss of earning capacity.

The table below summarises these changes.

The Civil Liability Act placed a ‘cap’ (maximum limit) of

$350,000 on damages for non-economic loss. (This was

subsequently adjusted to $384,500 in line with

indexation.) Non-economic loss refers to damages

awarded for pain and suffering, commonly known as

general damages. Under the Act, the maximum amount

can only be awarded in a ‘most extreme case’. There is also

a threshold test for the award of non-economic loss,

which eliminates small claims. Section 16(1) states that:

‘No damages may be awarded for non-economic loss

unless the severity of the non-economic loss is at least 15

per cent of a most extreme case.’

Changes to the law have been implemented in two

separate waves. The first, known as Stage 1 reforms,

aimed primarily at decreasing the number of claims and

the cost of claims by placing limits on the amounts that

can be paid in various circumstances. The Stage 2 reforms

were far broader and involved a fundamental reassessment

of the law of negligence and personal injury.

STAGE 1 REFORMS

Most of the Stage 1 reforms were implemented through

the passage of the Civil Liability Act 2002 (NSW). The

remaining changes, which related to the way in which

lawyers can advertise personal injury services, were

effected by amending the Legal Profession Regulation

2002.

There is also a cap on economic loss, that is, loss of actual

earnings and of future earning capacity. The cap is

calculated at three times the average weekly earnings. This

is the case even if the person was earning more or

expected to earn more than that limit. Furthermore, the

discount rate to damages for

future economic loss increased

HOT TIP

from three to five per cent,

NSW legislation is

reducing the final figure

available at

awarded.

www.legislation.nsw.gov.au

Limits on damages

The Civil Liability Act 2002 (NSW) was assented to in

June, but commenced operation on 20 March 2002. This

is what is known as ‘retrospective’ legislation. The Civil

Liability Act restricts the level of compensation available

for personal injury negligence actions by placing limits on

Select ‘Browse in Force’

option.

Matter restricted

Cap or restriction

Section of Act

cap on non-economic loss

(general damages or pain and suffering)

$350,000

(later adjusted to $384,500)

s 16(2)

threshold for access to non-economic loss

15% of a most extreme case

s 16(1)

cap on economic loss

(loss of earnings and earning capacity)

3 � average weekly earnings

s 12(2)

discount to damages for future economic loss

5%

s 14(2)

exemplary, punitive and aggravated damages

cannot be awarded for negligence

s 21

family care (gratuitous attendant care)

reduced or not available

s 15

Changes to the law in New South Wales

9

The Act also specifies that aggravated, exemplary and

punitive damages cannot be awarded in personal injury

negligence cases. This means extra damages cannot be

awarded in an attempt to ‘punish’ the defendant for their

wrongdoing.

A new Part IA was inserted into the Civil Liability Act,

which was based on recommendations made in the Ipp

report (The Review on the Law of Negligence). The effect of

section 5B is that a person can only be found to be

negligent if:

Damages for gratuitous attendant care, that is, unpaid

care of a nursing/domestic nature generally carried out by

family members, are difficult to obtain. They are reduced

or in many cases not available.

> the risk was foreseeable (the person knew or ought to

have known of the risk); and

Advertising personal injury legal services

Parts of the Stage 1 reforms were aimed at reducing the

way that barristers and solicitors advertise personal injury

services. This was initially done by amending the Legal

Profession Regulation 1994 (NSW). This regulation was

subsequently repealed and replaced by the Legal Profession

Regulation 2002 (NSW).

Lawyers cannot advertise personal injury services, except

in some very restricted ways. For instance, they can have

a sign displayed at their place of business that states their

name, contact details, and accredited specialty. Similar

information can be published in a practitioner directory.

The restrictions do not apply in the case of advertising

services to existing clients, or to people on the lawyers’

premises, as long as the advertisement cannot be seen

from outside the premises. Other exceptions exist: see

sections 140 and 140A of the regulation. The regulation

stipulates that contravention of the advertising

restrictions can amount to professional misconduct.

STAGE 2 REFORMS

The Stage 2 reforms were much broader, having a

fundamental impact on the law of negligence itself. They

were not confined to those issues arising solely from public

liability insurance increases; they also had an impact on

other personal injury actions such as those relevant to

medical indemnity insurance. The Civil Liability

Amendment (Personal Responsibility) Act 2002 (NSW)

made changes to various Acts, in particular, the Civil

Liability Act 2002. Some parts commenced operation on

6 December 2002, others on 10 January 2003.

It is not possible to provide a comprehensive analysis of

every reform, but major areas are outlined. Further details

can be obtained by reading the legislation. See also the

further reading section on page 24. A discussion of

whether the reforms have been effective can be found in

‘Conclusion: Are the reforms working?’ (see p22).

General principles of negligence established

The amendments set down various provisions that in

some cases confirm the common law, in other cases

override previous inconsistencies in the common law. For

an outline of the common law of negligence see page 1

Overview.

10

HOT TOPICS 51 > Personal injury

> the risk was ‘not insignificant’; and

> a reasonable person in that position would have taken

precautions against the risk of harm.

To assist courts in deciding whether a reasonable person

would have taken precautions against a risk of harm in

those circumstances, the court is to consider:

> the probability that the harm would occur if care were

not taken;

> the likely seriousness of the harm;

> the burden (ie, costs and difficulty) of taking

precautions to avoid the risk of harm;

> the ‘social utility’ of the activity that creates the risk of

harm (whether it can be seen as a ‘worthwhile’ activity).

Section 5C states that the fact that a risk of harm could

have been avoided by doing something differently does

not of itself give rise to liability for the way things were

done. Taking action that would have avoided the risk,

after an action has occurred, does not in itself constitute

an admission of liability in connection with the risk.

General principles are also set down with regard to

causation – the link between a breach of the duty of care

and the injury suffered that is required by common law.

Under section 5D, two components are required to

determine that negligence caused the harm:

> ‘factual causation’ – the negligence was a necessary

condition of the occurrence of the harm; and

> ‘scope of liability’ – that is, it is appropriate for the

scope of the negligent person’s liability to extend to the

harm so caused.

Section 5E places the onus of proof regarding any fact

relevant to the issue of causation onto the plaintiff.

Assumption of risk principles established

Sections were added to the Civil Liability Act to deal with

the assumption of risk. This was an area that seemed to

have been watered down by the common law over the

previous decade. Section 5H states that there is generally

no duty to warn of ‘obvious risks’, unless the plaintiff has

requested such information from the defendant; or there

is a law requiring a warning; or where the defendant is

providing professional services.

Obvious risks are defined by s 5F to mean risks that

would have been obvious to a reasonable person in that

position. A risk of something occurring can be an obvious

risk even though it has a low probability of occurring.

Risks can be obvious even if the risk (or a condition or

circumstance giving rise to the risk) is not prominent,

conspicuous, or physically observable.

Injured people are presumed to be aware of obvious risks.

It is enough to be aware of the type or kind of risk, even

if they are not aware of the precise nature or extent of the

risk. Similarly, s 5I says there is no liability in negligence

for harm suffered as the result of the materialisation of an

‘inherent risk’. An inherent risk is a risk of something that

cannot be avoided by the exercise of reasonable care and

skill. However, the section does not exclude liability

regarding the duty to warn of such risks.

Determining standard of contributory negligence

Section 5R states that the principles applying to whether

a person has been negligent also apply to contributory

negligence. That is, the standard of care required of the

injured person is that of a reasonable person in that

position. The matter is determined on the basis of what

that person knew or ought to have known at the time.

Section 5S holds that it is open for a court to determine a

reduction in damages of 100 per cent if it thinks it just

and equitable to do so. The result of this would be that

the claim for damages is defeated.

Creation of a presumption

of structured settlements

Compensation for personal

injury caused by negligence

was typically awarded by the

courts as a single lump sum.

This was also generally the case

for settlement agreements.

However, the Stage 2 reforms

included calls for an alternative

to lump sums.

HOT TIP

Contributory negligence

refers to the issue of

whether the person injured

was partly (or wholly)

responsible for their injury

due to their own

negligence. That is, they

themselves may also have

been to blame for failing to

take precautions against

the risk of harm. Not

looking where they were

going, running over a wet

surface while wearing

slippery shoes, swimming in

dangerous waters – these

are all examples of possible

contributory negligence.

‘Structured settlements’ involve

a small lump sum payment plus

periodic payments for life.

These periodic payments are

funded by an annuity,

purchased by the defendant (or

its insurer) on behalf of the

plaintiff. An annuity is a

financial product provided by life insurance companies,

and makes regular payments. The advantages and

disadvantages of structured settlements are summarised in

the following table.

Advantages of structured settlements

Disadvantages of structured settlements

> plaintiff benefits from an increased after-tax award of

compensation and a cash flow that can be guaranteed

for life

> annuities that make up part of structured settlements

incur tax, whereas lump sum payments are non­

taxable (this has since changed – see note below)

> a structured settlement can be linked to inflation

ensuring its adequacy over the years

> lump sums provide greater flexibility and choice in

determining how a compensation payment is best

spent than structured settlements

> compensation payout is not susceptible to the

fluctuating investment returns of an investment lump

sum

> structured settlements are flexible

> defendant’s insurer will have to pay less money overall

in compensation if it is paid in instalments rather

than in a lump sum (estimates range between 10 to

15 % lower cost than lump sum)

> plaintiffs who deplete their lump sum early often

turn to the social security system, therefore the

Federal Government will benefit from the use of

structured settlements through reduced welfare

payments (despite lower tax receipts)

> structured settlements shift the risk of living too long

from the plaintiff to life insurance companies, which

are better able to handle that risk

> a lump sum payment offers a plaintiff greater

potential to change his or her lifestyles or career after

an injury, which is critical to recovery for many

patients

> lump sum payments provide certainty and finality to

litigation

> possible psychological benefit in receiving a lump

sum payout, in terms of empowering a plaintiff to

take control of his or her life

> possible associated costs of administering structured

settlements

> risk that the provider of an annuity may go bankrupt

(Source: Lozusic R, Public Liability – an update: Briefing Paper

11/2002, Parliament of New South Wales, pp 21-2)

Changes to the law in New South Wales

11

Note: one of the main disadvantages of structured

settlements was that they attracted tax, whereas a lump

sum didn’t – this has since changed. The Taxation Laws

Amendment (Structured Settlements and Structured Orders)

Act 2002 (Cth) amended the Income Tax Assessment Act

1997 (Cth), the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (Cth),

and the Life Insurance Act 1995 (Cth).

Periodic payments derived from structured settlements

and structured orders entered into on or after 26

September 2001 are tax-exempt.

Structured settlements and

orders must meet various

criteria in order to receive the

Structured settlements are

favourable tax treatment. There

the result of an agreement

between parties, while

is a compulsory component – a

structured orders are the

personal injury annuity that

result of a court order,

provides the injured person with

often without agreement by

a minimum level of monthly

the parties.

payments for as long as they

live. The minimum level of the

annuity is equal to the basic age pension and pension

supplement. This component is basically for the payment

of future medical treatment, nursing care and other living

expenses. There are also optional components, including

an immediate cash component. This is a lump sum paid

immediately so it can be used to pay costs, debts,

purchase equipment and so on. Another option is to

include a personal injury lump sum – a single premium

paid by the defendant or their insurer in return for an

agreement to pay a tax-free lump sum at an agreed future

date or dates. This can be used to cover expected future

costs, such as the upgrading or replacement of

equipment.

HOT TIP

With the taxation disadvantage settled, structured

settlements are gaining popularity. New provisions were

added to the Civil Liability Act to further encourage the

making of structured settlements.

Section 23 requires the court to give the parties to

proceedings a reasonable opportunity to negotiate a

structured settlement. Section 24 allows the court to

make consent orders for structured settlements. And

section 25 places an obligation on legal practitioners to

advise plaintiff clients in writing as to the availability of

structured settlements and the desirability of their

obtaining independent financial advice.

Mental harm

Mental harm means impairment of a person’s mental

condition. Part 3 of the Civil Liability Act deals with

mental harm arising in connection with personal injury.

Section 29 states that plaintiffs are not prevented from

recovering damages simply because the personal injury

arose wholly or in part from mental or nervous shock. But

then section 30 goes on to outline the limits that exist on

12

HOT TOPICS 51 > Personal injury

recovery for pure mental harm arising from shock.

Plaintiffs are not entitled to damages for pure mental

harm unless:

> the plaintiff witnessed, at the scene, the victim being

killed, injured or put in peril; or

> the plaintiff is a close family member of the victim (that

is, parent, spouse, partner, child, or sibling).

The nature of the duty of care owed is further explained

in section 32. A person does not owe a duty of care to not

cause mental harm unless they ought to have foreseen that

a person of ‘normal fortitude’ might, in the

circumstances, suffer a recognised psychiatric illness if

reasonable care were not taken.

Strengthening defences regarding intoxicated

plaintiffs

‘Intoxication’ refers to being under the influence of

alcohol or a drug, regardless of whether the drug is taken

for a medicinal purpose and whether it is taken lawfully.

The effect of intoxication on the duty and standard of

care is covered by section 49, which states that:

> in determining whether there is a duty of care, it is not

relevant to consider the possibility that intoxication has

exposed someone to increased risk because their ability

to exercise reasonable care and skill is impaired;

> a person is not owed a duty of care merely because they

are intoxicated;

> the fact that someone is intoxicated does not of itself

increase the standard of care owed to them.

Section 50 goes on to add that, if the person’s capacity to

take reasonable care and skill is impaired due to

intoxication, a court is not to award damages unless it is

satisfied that the injury is likely to have occurred even if

the person had not been intoxicated. In such situations, a

person is presumed to have been contributorily negligent

unless the court is satisfied that the person’s intoxication

did not contribute in any way to the cause of the injury.

This section does not apply if the intoxication was not

self-induced.

Strengthening defences regarding injuries

received in course of crime

Under the common law, no duty of care is owed to

someone who is engaged in criminal activity. This

provision was codified in the Civil Liability Act as section

54, and then further amended by Civil Liability

Amendment Act 2003. Criminals are not to be awarded

damages if the injury or death occurred at the time of or

following conduct that, on the balance of probabilities,

constitutes a serious offence, where that conduct

contributed materially to the injury or risk of injury. If a

mentally ill patient commits a serious offence, damages

are limited: see section 54A.

RECENT LEGISLATION ON PERSONAL INJURY*

Name of Act

Act amended

Date of Effect

What the changes mean

Commonwealth

Taxation Laws Amendment

(Structured Settlements and

Structured Orders) Act 2002

Income Tax Assessment 19 Dec 2002

Act 1997

removes tax barriers to structured settlements

Trade Practices Amendment

(Liability for Recreational

Services) Act 2002

Trade Practices Act 1974 19 Dec 2002

allows people to sign waivers and assume the risk of

participating in risky recreational activities

Commonwealth Volunteers

Protection Act 2002

Trade Practices Amendment

(Personal Injuries and Death)

Bill 2003

24 Aug 2003

Trade Practices Act 1974 13 July 2004

exempts Commonwealth volunteers from liability

prevents claims for damages for injuries or death

resulting from contraventions the Trade Practices Act

1974

New South Wales

Civil Liability Act 2002

20 March 2002

> upper limits imposed for non-economic loss

($350,000) and lost earnings (three times NSW

average weekly earnings)

> application of a threshold of 15% impairment for

general damages

Civil Liability Amendment

(Personal Responsibility)

Act 2002

Civil Liability Act 2002

6 Dec 2002 for

most, Sch 1[5]

1 Dec 2003

> allows people to sign waivers and take personal

responsibility for risk

> protects volunteers and ‘good Samaritans’

> ensures that saying ‘sorry’ does not represent an

admission of guilt

> imposes new limitation periods for personal injury cases

Civil Liability Amendment

Act 2003

Civil Liability Act 2002

19 Dec 2003,

except Sch 2 on

1 Dec 2004

> no damages to be awarded for the costs of rearing

a child (unless child has disability)

> criminals cannot be awarded damages

Civil Liability Amendment

(Offender Damages) Act 2004

Civil Liability Act 2002

> deals with damages for negligence for death or injury

suffered by offenders in custody

Civil Liability Amendment

(Offender Damages) Act 2005

Civil Liability Act 2002

> deals further with damages for negligence for death or

injury suffered by offenders in custody

*Note: This table does not include legislation relating to workers compensation accidents or motor vehicle accidents.

NEW LEGISLATION IN OTHER STATES

Australian Capital Territory

Queensland

Tasmania

> Civil Law (Wrongs) Act 2002

> Civil Liability Act 2003

> Civil Liability Act 2002

> Civil Law (Wrongs) Amendment Act

2003

> Personal Injuries Proceedings Act 2002

> Civil Law (Wrongs) (Proportionate

Liability and Professional Standards)

Amendment Act 2004

South Australia

Northern Territory

> Statutes Amendment (Structured

Settlements) Act 2002

> Consumer Affairs and Fair Trading

(Amendment) Act 2003

> Personal Injuries (Civil Claims)

Act 2003

Victoria

> Wrongs (Liability and Damages for

Personal Injury) Amendment Act 2002

> Recreational Services (Limitation of

Liability) Act 2002

> Law Reform (Ipp Recommendations)

Amendment Act 2000

> Wrongs and Other Acts (Public Liability

Insurance Reform) Act 2002

> Wrongs and Limitation of Actions Acts

(Insurance Reform) Act 2003

> Wrongs and Other Acts (Law of

Negligence) Act 2003

Western Australia

> Civil Liability Act 2002

> Civil Liability Amendment Act 2003

> Volunteers (Protection from Liability)

Act 2002

Changes to the law in New South Wales

13

As a related matter, the Civil Liability Amendment

(Offender Damages) Act 2004 introduced a new Part 2A

which came into effect from 19 November 2004. The

Part places limitations on the ability of offenders to claim

damages for personal injury against ‘protected defendants’

(such as the Crown and its servants) for injuries arising

while they are in custody.

Protection of good Samaritans who assist in

emergencies

image unavailable

The intention of this reform was to protect ‘good

Samaritans’ – people who voluntarily help in emergencies

– to ensure that such people are not at risk of being

judged after the event of not having helped well enough.

This was basically already the position at common law,

but nevertheless a new Part 8 was added to the Civil

Liability Act to specifically deal with good Samaritans.

Section 57 states that a good Samaritan does not incur

any personal civil liability regarding their act or omission

in an emergency when assisting a person who is

apparently injured or at risk of being injured. But there

are some situations where the protection does not apply:

> where it was the good Samaritan’s actions that caused

the injury or risk of injury in the first place; or

> where the good Samaritan failed to exercise reasonable

care and skill because their ability to do so was

significantly impaired because they were (voluntarily)

intoxicated; or

> where a person is impersonating a health care or

emergency services worker or a police officer, or

otherwise falsely represents that they have skills in

connection with emergency assistance.

Protection of community organisations and

volunteers

A related issue is the protection of volunteers and

community organisations for the purposes of ‘community

work’. That is, work that is not for private financial gain

performed for charitable, sporting, educational or cultural

purposes.

Section 61 holds that a volunteer is not liable for any act

or omission done in good faith when doing community

work organised by a community organisation or as an

office holder of a community organisation.

The protection does not apply if (among other things):

> the volunteer was engaged in a criminal offence at the time

> the volunteer was intoxicated

> the volunteer was acting outside the scope of his/her

activities or contrary to the community organisation’s

instructions.

Also, the requirement for incorporated associations to

have $2 million of public liability insurance was repealed

14

HOT TOPICS 51 > Personal injury

from the Associations Incorporation Regulation 1999, on

10 May 2002.

Apologies

The provisions of Part 10 state that an apology made by

a person does not constitute an express or implied

admission of fault or liability. Evidence of an apology is

not admissible in civil proceedings as evidence of fault or

liability in connection with that matter.

Statute of limitations

A limitation period works by limiting the time within

which a plaintiff can commence proceedings. Changes to

the Limitation Act 1969 (NSW) mean that a case cannot

be brought after the expiration of whichever is the first to

expire out of:

> three years running from the date on which the cause of

action is discoverable to the plaintiff; or

> twelve years from the time of the act or omission that is

alleged to have resulted in the injury.

See section 50C; exceptions exist for minors (section 50E)

and cases of disability (section 50F).

Recreational activities and risk warnings

The reforms to the law in this area are described under the

section headed ‘Sporting bodies’.

Statutory immunity for public authorities

This is dealt with under the section headed ‘Public

authorities’.

Changes to the medical negligence test

For details, please refer to section headed ‘Medical

negligence’.

Sporting bodies

THE LAW BEFORE THE REFORMS

Traditionally, participants in sporting games and activities

were not able to sue for negligence for injuries received.

This was because the law recognised that sport contained

certain inherent risks: if people are prepared to be

involved in the sport, they are prepared to take on the risk

that they might suffer certain injuries.

However, a High Court case in the late 1960s changed

the law significantly. In Rootes v Shelton , the High Court

stated that just because an injury occurred while playing

sport, that was not enough to exclude it from the laws of

negligence. Also, the fact that the activity contained

inherent risks was not enough to eliminate a duty of care:

see case study.

Since that case, courts have found that, in the context of

sporting events, a duty of care can be owed to many

people. Various cases have held that a duty exists to other

participants (amateur or professional), volunteers,

coaches, trainers and even to spectators. But who exactly

owes the duty of care? Court cases have found that a duty

of care may be owed by:

> other participants in the sport

> volunteers

> coaches

> trainers

> sporting organisations (either directly or vicariously –

vicarious liability involves an employer being liable for

the actions of their staff )

CASE STUDY

ROOTES v SHELTON

In this case, a water skier was severely injured following a

collision with a stationary boat. The skier sued the driver of

the towing boat for negligence. More specifically, he sued the

driver for failing to take due care in the control of the boat

and for failing to warn him of the presence of the stationary

boat, which was standard practice.

The New South Wales Supreme Court (Court of Appeal) had

found that the boat driver did not owe a duty to the plaintiff.

This was because they were both participants in a sport,

who accepted the risks of injury that might be involved with

taking part.

However, the High Court overturned this on appeal. Chief

Justice Barwick made some statements on negligence and

sport in general, before turning to the specifics of this case:

‘By engaging in a sport or pastime the participants may

be held to have accepted risks which are inherent in that

sport or pastime: the tribunal of fact can make its own

assessment of what the accepted risks are: but this does

not eliminate all duty of care of the one participant to the

other. Whether or not such a duty arises, and, if it does,

its extent, must necessarily depend in each case upon its

own circumstances: but, in my opinion, they are neither

definitive of the existence nor of the extent of the duty;

nor does their breach or non-observance necessarily

constitute a breach of any duty found to exist.’

Rootes v Shelton [1967] HCA 39; (1967) 116 CLR 383

available at http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/cases/cth/

HCA/1967/39.html

> occupiers and owners of sports premises, due to the

laws of occupiers’ liability.

WAIVERS AND

WARNINGS

A more recent High Court case found that the duty of

care in sports, however, does not necessarily extend to

bodies that make the rules for the sport: Agar v Hyde

[2000] HCA 41. In this case, the question was whether a

duty of care was owed by a rugby union rule making body

to the players. Chief Justice Gleeson held that,

‘Undertaking the function of participating in a process of

making and altering the rules according to which adult

people, for their own enjoyment, may choose to engage in

a hazardous sporting contest, does not, of itself, carry

with it potential legal liability for injury sustained in such

a contest.’ available at http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/cases/

cth/high_ct/2000/41.html

The Stage 2 reforms included

the introduction of waivers and

warnings in the context of risky

activities. More specifically, the

reforms would allow clauses to

be inserted into contracts for the

supply of recreational services

that limit or exclude the liability

of the service providers. Also,

the provision of risk warnings

would be able to operate as a

good defence for risky entertain­

ment or sporting activities.

HOT TIP

Occupiers and owners of

sports premises have a duty

to maintain safe premises,

for example in playing fields

and leisure centres. They

need to provide adequate

warnings, such as in the

form of signs pointing out

the relevant risks. The

existence of warning signs,

however, had been found to

not necessarily exempt an

occupier from their duty to

provide safe premises.

Sporting bodies

15

The Australian Plaintiff Lawyers Association (APLA, now

known as the Australian Lawyers Alliance) broadly

supported such changes. However, they did state that care

would be needed in the drafting to protect children and

people with mental disabilities. In their submission to the

Negligence Review Panel, they said:

image unavailable

APLA supports the exploration of the use of waivers or

disclaimers to enable fully informed adults to voluntarily

assume the risks inherent in certain activities. However,

it is essential that these disclaimers are only available

to those who can fully appreciate the nature and extent

of the risks that they undertake. They should only apply

to inherently risky activities and the risks involved

should be fully articulated before the assumption of risk

can be effective.

In their submission to the Negligence Review Panel, the

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission

(ACCC) expressed concerns that the reforms could lead

to risks being inappropriately transferred to consumers.

Their concern centred on the argument that consumers

are not as well placed as suppliers to gauge the risks

involved in recreational services and to insure against the

consequences of those risks.

WHAT THE LAW IS NOW

As part of the Stage 2 reforms, the Civil Liability

Amendment (Personal Responsibility) Act 2002 (NSW)

added some new provisions to the Civil Liability Act 2002

(NSW) dealing with recreational activities: Pt 1A Div 5.

‘Recreational activities’ are defined in Division 5 as

including any sport (whether organised or not), any

leisure pursuit, and any activity engaged in at a place

where people ordinarily engage in sport, leisure or

relaxation activities (such as parks, beaches, open public

space). A dangerous recreational activity is one that

involves a significant risk of physical harm.

Section 5L states that a person is not liable in negligence

for harm suffered due to the materialisation of an obvious

risk of a dangerous recreational activity – whether the

plaintiff was aware of the risk or not.

In line with the calls for change discussed above, changes

were made to the law regarding risk warnings and

exclusion clauses in contracts.

Section 5M deals with risk warnings. A person does not

owe a duty of care to someone engaging in a recreational

activity if the risk of the activity was the subject of a risk

warning to that participant. A risk warning must be given

in a manner that is reasonably likely to result in people

being warned of the risk before engaging in the activity. It

is not necessary to establish, however, that the person

received or understood the warning – or even that they

were capable of receiving or understanding it. Risk

warnings can be given orally or in writing, for instance, by

means of a sign. They need not be specific to the

16

HOT TOPICS 51 > Personal injury

particular risk. Rather, they can be a general warning of

risks that include the particular risk concerned, as long as

they warn of the general nature of the particular risk.

According to the section, there are some situations where

defendants cannot rely on risk warnings. These are where:

> the person who suffered harm was an incapable person

(unless they were under the control of or accompanied

by someone else who received the risk warning, or the

warning was to a parent of the incapable person)

> the warning was not given by or on behalf of the

defendant or the occupier of the premises

> there was a contravention of safety laws

> the warning was contradicted by any representation as

to risk made by or on behalf of the defendant

> the defendant had required the plaintiff to engage in

the recreational activity.

Section 5N deals with waiver of contractual duties of care

for recreational activities. It states that a contract for the

supply of a recreation service may ‘exclude, restrict or

modify any liability to which this Division applies that

results from breach of an express or implied warranty that

the services will be rendered with reasonable care and skill’.

It goes on to say that nothing in the written law of New

South Wales renders such a contract void or unenforceable,

or authorises a court to refuse to enforce the term, declare

it void or vary it. The section does not apply, however,

where there have been breaches of safety regulations.

This change acts in conjunction with an amendment

made to the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth). Section 74(1)

of that Act has long created an implied warranty that

services will be rendered with due care and skill, and

section 68 voids any contract terms that exclude this

warranty. However, a new section now deals specifically

with recreational services. Section 68B allows

corporations who provide recreational services to insert

clauses that limit their liability for death or personal

injury arising from the supply of those services.

The new laws appear to be very restrictive. Undoubtedly,

future cases will turn on the wording of the risk warnings

and the exclusion clauses.

Public authorities

Public authorities include the Crown, government

departments, local councils, and public and local

authorities constituted by legislation. Their

responsibilities are broad, and, particularly in the

case of local councils, encompass a wide range

of services into which the general public comes

into daily contact.

As an aside, it is worth noting that the Civil Liability

Regulation 2003 (NSW) regards private schools to be

public authorities for the purposes of the Civil Liability

Act 2002 (NSW). This means the same considerations

apply to public and private schools when it comes to

liability for negligence.

WIDE EXPOSURE

Although this discussion generally applies to all public

authorities, it focuses on local councils. This is because

the breadth of their activities and responsibilities tends to

give them the widest potential for exposure. Many of the

facilities provided by local councils are intended for

recreational and sporting activities. These include

swimming pools, sporting grounds, playgrounds and

community centres. Leisure and sporting activities by

their nature contain more risks than other activities, thus

increasing a council’s exposure to liability for personal

injury actions.

In addition, councils are responsible for maintaining

infrastructure such as roads and footpaths. These are

continuously used by members of the public – yet again

exposing councils to a high potential for liability for

negligence causing personal injury.

Looking at roads and footpaths in particular, in the past,

a highway authority (which can be a local council) did

not incur civil liability ‘… by reason of any neglect on its

image unavailable

Public authorities

17

HOT TIP

Malfeasance is a

wrongdoing that is

unlawful, it can be either a

crime or a tort for instance,

trespass. Misfeasance in

negligence is the doing of

something to a standard

that falls short of the

required standard. Road

authorities have always

been liable for misfeasance

if they actually created

dangers on the road.

Nonfeasance is the failure

to carry out a duty. The

nonfeasance rule

traditionally protected road

authorities from actions in

negligence regarding a

failure to either maintain or

repair the roads. It dates

back to the Middle Ages

when roads were privately

owned. The distinction

between nonfeasance and

misfeasance has been

disputed in many cases.

Distinctions were made

based on the facts of

cases, so over time the

so-called ‘highway rule’

eroded.

part to construct, repair or

maintain a road or other highway’: Buckle v Bayswater Road

Board 5. This principle was

known as the ‘highway rule’.

But a recent High Court case

abolished this immunity. In

Brodie v Singleton Shire Council 6

a bridge collapsed when a heavy

truck drove over it. The court

removed the highway rule and

replaced it with the ordinary

principles of negligence. The

court criticised the rule because

it had developed in a way that

gave rise to ‘illusory distinc­

tions’. They were referring to

the differences between non­

feasance and misfeasance, and

their consequences. The High

Court stated that this distinc­

tion provided no incentive for

highway authorities to take

action to repair damage.

CHANGES TO THE LAW

The issue of public authorities’

duties was one of the areas dealt

with by the Stage 2 reforms. The

broad range of duties of public

authorities was recognised, and

the limited resources available to them to perform such

duties. The reforms aimed to ensure that the existence of

a power does not necessarily imply a duty to exercise

that power; except where there is a statutory obligation

to do so.

The Civil Liability Amendment (Personal Responsibility)

Act 2002 (NSW) added Part 5 to the Civil Liability Act

2002 (NSW). Section 42 states that the following

principles apply in determining whether a public

authority has a duty of care or has breached a duty of care:

> the functions required to be exercised are limited by the

financial and other resources reasonably available to the

authority for the purpose of exercising those functions

> the general allocation of those resources by the

authority is not open to challenge

> the authority can rely on evidence of its compliance

with general procedures and standards as evidence of

the proper exercise of its functions.

Under section 43, an act or omission by an authority does

not constitute a breach of statutory duty unless it was ‘so

unreasonable that no authority having the functions of

the authority in question could properly consider the act

or omission to be a reasonable exercise of its functions’.

A public authority is not liable for a failure to prohibit or

regulate an activity unless it could have been compelled to

by a court: see section 44.

For example, an authority that does not use its regulatory

authority to close a fishery would not be liable unless the

courts could have compelled them to exercise that

function.

The nonfeasance rule for highway authorities is now

specifically covered by the legislation, which uses the term

‘roads authority’. Section 45 states that a roads authority

is not liable for harm arising from a failure to carry out

road work or to consider carrying out road work, unless

at the time it had actual knowledge of the particular risk

that resulted in the harm. If a roads authority did know

about a particular risk, it will still be able to rely on the

general protection of being able to allocate resources

without challenge.

Similarly, section 46 holds that the fact that a public

authority exercises or decides to exercise a function does

not of itself indicate a duty to exercise that function. Nor