Background for Teachers: Water Cycle and Pathways What is

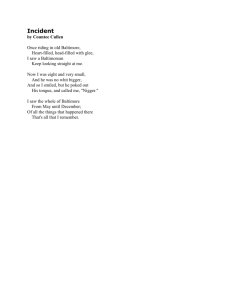

advertisement

Lesson 1 – Urban, Schoolyard and Home Hydrology Background for Teachers: Water Cycle and Pathways What is hydrology and why is it important? Hydrology Basics: Hydrology is the area of science that deals with the study of the waters of the earth and its atmosphere (SWEAP glossary). Water is everywhere, making up over 70% of our bodies, and is an invaluable natural resource for plants, animals, and people. Water is strong enough to change the surface of the Earth through erosion, and its absence is powerful enough to kill a person in three to four days. The Hydrologic Cycle: The Hydrologic Cycle, or water cycle, is a series of processes by which water passes from the atmosphere to the Earth and back to the atmosphere. The hydrologic cycle includes the following components: • Precipitation: Water falling to the Earth from the atmosphere in the form of rain, snow, sleet, or hail. • Surface Runoff: Water that hits the Earth and then moves along the top of the land surface, often carrying materials (soil, etc.) with it. • Infiltration/Percolation: Water moving into the soil under the force of gravity. Once in the soil, the water may be taken up by living things, or it may move horizontally along flow paths within the soil under the force of gravity along slopes. Otherwise, the water moves straight down via gravity, eventually reaching the groundwater. • Evaporation: Water changing from a liquid to a gaseous state (water vapor). This requires a source of energy – usually, the sun – and results in cooling of the evaporative surface. Water vapor subsequently rises from oceans, rivers, lakes, soils, and vegetation into the atmosphere. • Transpiration: Evaporation from moist surfaces of plants. Most transpiration takes place in the moist inner parts of leaves at the same time CO2 is being absorbed and O2 is being released during photosynthesis. The gasses are exchanged through pores – called stomata – in one or both surface of leaves, and sometimes stems. • Condensation: Conversion of gaseous water (water vapor) to a liquid (droplets) or solid (crystals) state. This takes place when warm, moist air is cooled, either by the air itself cooling or when it comes in contact with cool surfaces. Tiny water droplets or ice crystals then coalesce to form the visible drops or flakes we see in clouds. All water in the world is part of the hydrologic cycle – a bottle of water you just bought at the supermarket, a drop of morning dew glistening on a spider web, a rushing river, or a snowball you are about to throw at your brother. People don’t make new water to sell, they simply take water from one place, such as a river or lake, clean it (we hope), and put it in a fancy bottle. The total amount of water in the system does not change. Annual water loss from the surface of the earth is equal to the total annual precipitation. Schoolyard Hydro-Ecology Teachers’ Handbook - Baltimore Ecosystem Study Draft 2 – July 19, 2005 Lesson 1 - page 1 THE HYDROLOGIC CYCLE (http://www.ec.gc.ca/water/en/nature/prop/e_cycle.htm) Baltimore’s Hydrologic Cycle: The Natural to the Constructed (Information taken from http://www.baltimorecity.gov/government/dpw ) Baltimore was founded in 1729, and the first try at establishing a public water supply was in 1787 by the Baltimore Insurance company. Baltimore incorporated into a city in the year 1797. At that time people still got their drinking water from streams, ponds, springs, and wells. People were required to have buckets in their homes to fight fires. After the city was official, it began to build pumps in public places. The Baltimore Water Company was founded in 1804, which built a reservoir at the southeast corner of Calvert and Centre streets to hold water from the Jones Falls. The Jones Falls Waterworks was built in 1807. Other reservoirs were built later at higher levels, and a pipeline was constructed for distribution. The city of Baltimore bought the water company in 1854 for $1, 350,000, and created the city’s water department From 1858-862, the city constructed pipelines and water mains, and made improvements to the Jones Falls water supply – constructing Lake Roland Dam and the Reservoir, the Jones falls Conduit, Lake Hampden, and Mount Royal Reservoir. Druid Hill Reservoir was built in 1873 to meet the growing need for water supply in the city. A permanent supply from Gunpowder Falls was also completed in 1881. Lake Montebello was also constructed during this time, with a filtration station working by 1915. The filtration system was deemed necessary because of public health concerns, and a need to chlorinate the water. The lake was connected to Lake Clifton by conduit, as well as to Loch Raven Reservoir, which was built during the same time period. Schoolyard Hydro-Ecology Teachers’ Handbook - Baltimore Ecosystem Study Draft 2 – July 19, 2005 Lesson 1 - page 2 Between 1915 and 1950 the Loch Raven Dam, a second filtration plant at Lake Montebello, Prettyboy Dam, and the Gunpowder-Montebello Tunnel, and the Patapsco-Montebello Tunnel were all completed. The Department of Public Works was created in 1925, which took ownership of water distribution in the city. In 1956, the Ashburton Filtration Plant (Druid Park Drive), Liberty Dam, and Reservoir were completed in order to meet the growing need for water in Baltimore City. The Deer Creek Pumping Station was built in 1966, which allows the city to draw water from the Susquehanna River. In 1979 the Bureau of Water and Wastewater was established, which now controls the water in the city. Baltimore's Water Supply Today Source: http://www.ce.jhu.edu/mdcive/ The Baltimore City Bureau of Water and Wastewater supplies drinking water to over 1.6 million people. The water comes from two sources, the Gunpowder Falls and the north branch of the Patapsco River. Three concrete gravity dams, the Liberty on the Patapsco and the Prettyboy and Loch Raven on the Gunpowder Falls, create reservoirs. Water is brought through a 12-foot tunnel to the Montebello Filtration plant from the Loch Raven Reservoir. If the water level drops, the valves are opened at the Prettyboy Dam, and the water follows the course of the falls to refill Loch Raven. A 10-foot tunnel brings the water at the Liberty reservoir to the Ashburton Filtration plant. Both tunnels were constructed through solid rock. In the city's two filtration plants, the water is filtered, disinfected, and fluoridated. Everyday 480 million gallons of water are treated and distributed to the city through 3000 miles of water mains. Facts and Figures Directions Ashburton: in operation since 1956 Montebello: in operation since 1915, Loch Raven Dam: built 1912 crest: 420 feet above sea level Prettyboy Dam: built 1936; crest: 520 feet above sea level • • • • Prettyboy: On the I-83 take exit 31 and head west. Liberty: From the Baltimore Beltway take exit 18 on MD 26. It will cross over the reservoir. Montebello: From the Beltway take Perry Pkwy. (exit 30) south, The plant will be on both sides of the road just before 33rd. St. Loch Raven: From the Beltway take exit 28. Follow Provicence Rd. to Loch Raven Drive. Liberty Dam: built 1956 crest: 420 feet above sea level Implications of Modifying the Hydrologic Cycle When all of these changes were made to the area around Baltimore and the Urban system we know as Baltimore City was created, the hydrologic cycle in the area had to change… When people decide to make a change to any part of the earth’s system, such as building a new freeway or bulldozing a field, the rest of the system is affected. The reasons for these modifications to the hydrologic cycle in Baltimore had 3 main purposes: minimizing health Schoolyard Hydro-Ecology Teachers’ Handbook - Baltimore Ecosystem Study Draft 2 – July 19, 2005 Lesson 1 - page 3 hazards from water-borne diseases, supplying safe drinking water to the people in the area, and minimizing hazards from floods. Let’s explore, for a moment, the specific impacts that developing a city can have on the Hydrologic cycle, and also some of it’s consequences. Implications for the Hydrologic Cycle: as a city develops, the amount of pervious surfaces & impervious (surfaces that water can easily soak into such as grass and unpacked soil) decreases as the amount of impervious surfaces such as asphalt and concrete increase. Looking around you in Baltimore, there are very few areas of pervious surfaces – even many people’s backyards are covered in asphalt. This causes the following effects on the hydrologic cyle: • Decrease in infiltration and percolation: since most impervious surfaces are not penetrable by water, less water enters the shallow and deep subsurface areas of the ground. This leads to a reduction in infiltration and percolation in the soil • Decrease in throughflow: Since there is less water in shallow subsurface layers, there is a reduction in the soil moisture and throughflow in the area. • Decrease in groundwater recharge: there is less water that percolates to deeper subsurface layers, which leads to a decrease in sub-surface water resources (unless you have a lot of leaking pipes in the city, which might actually contribute to the level of water in the subsurface areas). • Decrease in detention storage: • Because impervious surfaces are smoother, water moves at higher velocities over the land, can pick up more debris with it (contributing to pollution in the form of runoff) and also can cause more erosion when it passes over surfaces that are not asphalt at higher velocities. • When construction occurs in the city, asphalt areas are generally designed so that they do not form ponds of water on them (who wants to step in a 3 foot deep puddle in a parking lot?) and instead of being held at the surface, this water is directed to gutters and storm drains that deliver the water to underground storm sewers pipes. • Decrease in interception storage: because there is less vegetation, most water that hits the land either evaporates from impervious surfaces, or runs off the surface of the land. • Increase in the amount of storm runoff • Increase in stream flooding: since water enters streams at faster rate via storm sewers than it did when it flowed over the surface of the land, the streams are more likely to flash-flood and cause greater damage to the surrounding area than if they were left in their more undeveloped state. • Decrease in base flow: If the pipes are not leaking too much in the city, there will be less sub-surface water, which means that less water in the city flows to streams as throughflow or groundwater flow. Summary: because of how we have changed the surface of the Baltimore area, we have to pay more attention to the way water moves in our city in order to keep the environment in balance and make sure that our actions do not have too many adverse impacts on our surroundings. As individuals in the Baltimore area we need to look to projects that remediate some of the effects of putting down these huge expanses of impervious surfaces in the city, and try to bring more balance back to the environment. Schoolyard Hydro-Ecology Teachers’ Handbook - Baltimore Ecosystem Study Draft 2 – July 19, 2005 Lesson 1 - page 4 References: Baltimore Department of Public Works http://www.baltimorecity.gov/government/dpw/wwwfacts.html Environment Canada http://www.ec.gc.ca/water/en/nature/prop/e_cycle.htm Maryland Civil Engineering Structures http://www.ce.jhu.edu/mdcive/ Parks and People Foundation www.parksandpeople.org Schoolyard Hydro-Ecology Teachers’ Handbook - Baltimore Ecosystem Study Draft 2 – July 19, 2005 Lesson 1 - page 5 Lesson 1 – Urban, Schoolyard and Home Hydrology Teacher’s Lesson Plan: Water Cycles and Pathways Objectives: Students will learn to describe the natural water cycle and urban water pathways in order to explain the intersections of the natural and created pathways of water in Baltimore. Content Standard(s): Please see the “Background” section of the handbook and pick out standards that are appropriate for your grade level. Read Aloud: The history of Baltimore’s water supply (attached) Context of Lesson: Students need to learn about how water moves where they live – both naturally and through constructed pathways. Vocabulary: 1. Hydrology: The scientific study of the waters of the earth and its atmosphere 2. precipitation: Process by which water falls to Earth from the atmosphere in the form of rain, snow, sleet, or hail. 3. surface runoff: Process by which precipitation and snowmelt moves along the Earth’s surface and drains or flows off the land. 4. transpiration: Process by which plants release water vapor into the atmosphere, most via structures of their leaves called stomata. 5. evaporation: Process by which water changes from a liquid to a gaseous state as it is heated by the sun and other energy sources; water vapor subsequently rises from oceans, rivers, lakes, soils, and vegetation into the atmosphere. 6. condensation: Process by which water vapor in the atmosphere cools and turns into liquid water or ice; water droplets or ice crystals coalesce to form clouds. 7. infiltration/percolation: Process by which water moves into the soil and travels downward, some reaching groundwater reservoirs. Warm Up: How many gallons of water fall if 1 inch of rain falls on 1 acre of land? Answer: 1 inch of rain falling on 1 acre of land is about 27,154 gallons of water. Background information: see “Teacher’s Background” Materials: 1. Human water use tally sheets for the class 2. Graphing Rainfall Data worksheets (1 per student or small group) 3. Materials for the Watershed lab (garbage bag one) 4. Journals 5. Chalkboard, whiteboard, or felt board for discussions 6. paper for KWL charts and notes Activities: 1. Students take 5 minutes to complete the warm up, and the teacher reviews the objectives for the day with them. Discuss possible answers to the warm up, and have that lead into a discussion of watersheds. 2. Discuss what a watershed is, and do the Watershed lab using garbage bags and food coloring to give students a greater understanding of exactly what a watershed looks Schoolyard Hydro-Ecology Teachers’ Handbook - Baltimore Ecosystem Study Draft 2 – July 19, 2005 Lesson 1 - page 6 like and how it works. 3. Introduce the textbook concept of the “natural” hydrologic cycle, and discuss key vocabulary terms above. For younger grades you may need to simplify some of the terms/definitions. 4. Students create a KWL (know, want to know, learned) chart about how they think water gets to their house . 5. Diagram the pathways of water: First the “Natural” hydrologic cycle, and then the “created” or engineered pathway as modified by human activity. Make sure to discuss how these two pathways intersect, and where. All students should create a diagram during this activity as you create it as a group on the board. Use of a Felt Board or post-its could be particularly helpful with this activity as you can move pieces around without erasing. 6. Read aloud: Baltimore’s water history from teacher background. 7. Students finalize their KWL chart by filling in what they learned. 8. Graphing Rainfall Data (see attached) 9. Journal activity: what are some problems that might happen if the urban water pathways break down? A – have students respond to the journal prompt B - share journal entries aloud C – make sure that students understand that pipe leaks can contribute to groundwater, and surface or storm water can overload sanitary water systems. 10. Wrap Up: Discuss the objective for the day and see if you met it as a class, discuss possible activities for future lessons (what students want to know more about). 11. Assign homework and discuss human water use tally concept Homework: Human Water Use Tally (discuss results in class in two days. Instead of using “Saturday” as the worksheet says, you may pick a day where all of the students will be focused on water. It could even be a school day, so long as they are focused on the activity all day long. Extensions: 1. Field Trip to sewage treatment plant and a reservoir 2. Alternate Field Trip: Prepare slides of a sewage treatment plant and one (or more) of the reservoirs around Baltimore and incorporate them into a PowerPoint Presentation to show to students (or put on paper and pass around) 3. Alternate Field Trip 2: Use “The Story of Baltimore’s Water Supply” (obtained from the department of public works bureau of water and waste water) and photocopy the pictures you feel are most relevant to the focus of your students, and either put them into a PowerPoint presentation to discuss, or else on paper to pass around and write about. 4. Storm Drain Stenciling (SLURPP) 5. Brochure (SLURPP) Resources: 1. The Story of Baltimore’s Water Supply – City of Baltimore Department of Public Works, Bureau of Water and Waste Water, November 1981. 2. See references in “Teacher’s Background” Schoolyard Hydro-Ecology Teachers’ Handbook - Baltimore Ecosystem Study Draft 2 – July 19, 2005 Lesson 1 - page 7 Lesson 1 – Urban, Schoolyard and Home Hydrology Student Lesson: The Water Cycle Name:______________________________________ Date:______________ Directions: Fill in the blanks on the diagram above with the names of the processes described below. • Storage - the process in which water pools in large bodies (like oceans, seas and lakes), in the soil, in groundwater, or in living things. • Condensation - the process in which water vapor (a gas) in the air turns into liquid water. Condensing water forms clouds in the sky. Water drops that form on the outside of a glass of icy water are condensed water. (Hint: this term appears twice in the diagram.) Schoolyard Hydro-Ecology Teachers’ Handbook - Baltimore Ecosystem Study Draft 2 – July 19, 2005 Lesson 1 - page 8 • Evaporation - the process by which liquid water becomes water vapor (a gas). Water evaporates from the surfaces of oceans, rivers, ponds, wetlands, puddles and lakes, from the surface of the land, and from melting snow fields. • Precipitation - the process by which water (in the form of rain, snow, sleet, or hail) falls from clouds in the sky. • Surface Runoff - water that flows over the surface of the land from rain or snowmelt, eventually reaching surface streams, rivers, canals, lakes, ponds, wetlands or the ocean. • Subsurface Runoff - water that flows in the soil, either along impervious layers, or in underground streams, drains, or sewers. • Transpiration - the process in which some water within plants evaporates into the atmosphere. Water is first absorbed by the plant's roots, then later exits by evaporating through pores in the plant. Schoolyard Hydro-Ecology Teachers’ Handbook - Baltimore Ecosystem Study Draft 2 – July 19, 2005 Lesson 1 - page 9 Lesson 1 – Urban, Schoolyard and Home Hydrology Student Lesson: Graphing Rainfall Data Below is a table of the amount of water received when an inch of rain falls on a city, and the area of each city (http://ga.water.usgs.gov/edu//earthrain.html) Amount of water received when an inch of rain occurs City Atlanta, GA Baltimore, MD Chicago, IL Cincinnati, OH Denver, CO Detroit, MI Honolulu, HI Houston, TX Jacksonville, FL Louisville, KY Milwaukee, WI New Orleans, LA New York, NY Philadelphia, PA Salt Lake City, UT Seattle, WA Washington, DC Area (square miles) 131.7 80.8 227.1 78.0 153.5 138.8 85.7 579.4 757.7 62.1 96.1 180.6 303.3 135.1 109.1 83.9 61.4 Amount of water (millions of gallons) 2,289 1,404 3,947 1,356 2,666 2,412 1,489 10,069 13,168 1,079 1,670 3,139 5,271 2,348 1,906 1,458 1,067 On a separate sheet of paper, make a line graph of the amount of rainfall vs. the area of a city. Please put the amount of rainfall on the y-axis, and the area of the city on the x-axis. Make sure your graph includes all required components (Title, axis, labels, spacing, increments). Schoolyard Hydro-Ecology Teachers’ Handbook - Baltimore Ecosystem Study Draft 2 – July 19, 2005 Lesson 1 - page 10 Lesson 1 – Urban, Schoolyard and Home Hydrology Demonstration Activity: Water in a Watershed Overview Students watch a simple demonstration and learn about watersheds, runoff, and pollution. Concepts • • • • A watershed (or drainage basin) is the area of land that contributes water to a stream or pond The flow of runoff and sewage in a watershed is directed by ridges—the high points that separate adjacent watersheds Everyone lives in a watershed Land use activities in a watershed can affect water quality and quantity Materials • • • • • • Shallow basin or tub Several sheets of newspaper White plastic garbage bag Spray bottle or atomizer Food coloring One piece of paper towel Procedure Create a simple watershed model by crumpling up several pieces of newspaper and placing them in the bottom of the basin. Cover the newspaper with plastic: this is the land surface. The uneven distribution of the paper should create a raised relief map with hills and valleys. Ask students what will happen to rain falling on the land surface. Where will it go? Where will it end up? Spray water on the plastic to test their predictions. (The water will be easier to observe if you add a little food coloring.) The water will flow from high points to low points in rivulets that represent streams and rivers and will collect in pools that represent lakes or the ocean. Explain that the area draining into each stream, river, or lake is called a watershed. Notice that every location on the plastic is part of a watershed. Use a tiny piece of paper towel soaked in food coloring to represent a source of contamination like motor oil or lawn fertilizer or a leaky septic system. (Make sure you use a different color of food coloring this time.) Ask students to predict what will happen to the contamination when it rains. Place the dyed piece of paper towel on the plastic watershed model and spray to make it rain. Watch as the “pollutant” flows into a stream and then into a nearby lake or ocean. Also notice that only one “watershed” is polluted unless the pollutant is on a divide. Schoolyard Hydro-Ecology Teachers’ Handbook - Baltimore Ecosystem Study Draft 2 – July 19, 2005 Lesson 1 - page 11 Lesson 1 – Urban, Schoolyard and Home Hydrology Student Lesson: Personal Water Use HOW MUCH WATER DO YOU & YOUR FAMILY USE? Students have been recruited to be water detectives! We want you to help us find out how much water families in your community are using. You are going to collect and record information on how much water you use at home this weekend on SATURDAY! (If you forget to do the survey on Saturday, then please do it on Sunday!) Here’s your job: • Please don’t change anything you normally do • Use the form on the other side of this page to record your water use for Saturday (count things away from the home too, like washing your hands or flushing the toilet) • For personal tasks, like brushing your teeth, or taking a shower we want you to count only your own activities • For things like washing dishes or doing laundry, please get your family to help you. We want to know about your household’s dishwashing and laundry on Saturday (if your family does laundry at a relative’s house or a Laundromat please count that too!) • Bring the form in on Monday. Lesson 1 – Urban, Schoolyard and Home Hydrology Schoolyard Hydro-Ecology Teachers’ Handbook - Baltimore Ecosystem Study Draft 2 – July 19, 2005 Lesson 1 - page 12 Student Worksheet: My Water Use Tally My Name: Water Detective___________________________ Day of Survey_________________________ Example: Activity Number of Times Total Number of Times Wash Hands Take a Bath 1111 1 4 1 ACTIVITY Bathroom: Washing Hands Number of Times Total Number of Times Brushing Teeth Flushing Toilet Showering: Fill in how many minutes you spend in the shower ______minutes Taking a bath Kitchen/Laundry Washing dishes by hand Washing dishes by dishwasher Doing a load of laundry Drinking Water Drinking a full glass of water Lesson 1 – Urban, Schoolyard and Home Hydrology Schoolyard Hydro-Ecology Teachers’ Handbook - Baltimore Ecosystem Study Draft 2 – July 19, 2005 Lesson 1 - page 13 Student Worksheet: Water Use Calculation Sheet ACTIVITY Total # Times Water Use Each Time Bathroom: Washing Hands 1 gallon Brushing Teeth 1 gallon Flushing Toilet 3 gallons Showering: Fill in how many minutes you spend in the shower ______minutes Taking a bath 2 gallons each minute Kitchen/Laundry Washing dishes by hand Washing dishes by dishwasher Doing a load of laundry Drinking Water Drinking a full glass of water Total Use (Column 1 x column 2) (hint: use # of minutes) 50 gallons 5 gallons 20 gallons 10 gallons .06 gallon Schoolyard Hydro-Ecology Teachers’ Handbook - Baltimore Ecosystem Study Draft 2 – July 19, 2005 Lesson 1 - page 14 Lesson 1 – Urban, Schoolyard and Home Hydrology Student Activity: Bonus Water Use Problem Part 1: Your mom is really excited about the work your class has been doing to learn about ways to save water. She wants to know whether or not she will be using less water taking a bath or a shower. • What do you need to know about her shower before you can work on solving this problem? ___________________________________________________ Part 2: Use your answer from part 1 (above) about how long your mom’s showers take, advise your mom whether she will use less water taking a bath or a shower. Remember to use your “Water Use Calculation Sheet” to help you answer this question • How much water will your mom use for her bath? • How much water will your mom use for her shower? • To save water, should your mom take a shower or a bath? Schoolyard Hydro-Ecology Teachers’ Handbook - Baltimore Ecosystem Study Draft 2 – July 19, 2005 Lesson 1 - page 15 Lesson 1 – Urban, Schoolyard and Home Hydrology Student Handout: Water Conservation Tips! - reading • Turn off the water when it’s not in use! o Don’t leave it running when you: Brush your teeth Soap up your hands Shampoo your hair • Keep your showers short! o Next time, buy a shower head that uses less water • When you take a bath, keep the water level low! • Always wait until you have a full load to wash your clothes or run the dishwasher • When you wash dishes by hand, fill the sink or a container with water for rinsing. Don’t leave the water running! • Keep a bottle of cold drinking water in the refrigerator instead of letting the sink water run until it’s cool each time you want a drink! • Always shut off the faucet when you are finished using water! • Check for faucet leaks and help get them fixed! • If you have water running waiting for it to get either hot or cold, slip a bucket under the tap. Use the water to water your lawn or plants! • Use a broom, not a hose, to clean your porch, front walk, or sidewalk! • Water your lawn in the early morning or evening when water will not evaporate as quickly! • Be sure to water the grass and flowers, not the sidewalk or street! Schoolyard Hydro-Ecology Teachers’ Handbook - Baltimore Ecosystem Study Draft 2 – July 19, 2005 Lesson 1 - page 16 Lesson 1 – Urban, Schoolyard and Home Hydrology Student Lesson: Storm Drain Internet Research Activity Name: ___________________________ Date:_______________ Storm Drain Research Internet Activity This activity is designed to help you learn about some devices that have been designed to help reduce the amount of pollution entering our waterways through storm drains, and to give you a chance to design your own. As you work through this activity, think about what you have already learned about storm water runoff, the storm drain network, and how pollution enters this system. The pages you will visit are designed for professionals in the field of low impact development, so try not to get caught up in the technicalities. Use the pictures on the websites and the attached vocabulary list to help you understand how each device works. Be creative with your own invention, you might just stumble onto something revolutionary! Good luck!! Part I: 1. Open up your web browser (ex: Internet Explorer) and type in the address “www.interstateproducts.com.” Click on storm water management products. Under the heading “catch basin protection,” click on ultra-curb guard. 2. Read about the ultra-curb guard and look at the pictures, clicking on them for enlarged images. Vocabulary question: Is this device an insert or an exert? (use the attached vocabulary sheet!) 3. Using words and/or pictures, explain what this device does and how it works. 4. On the attached chart, fill in the information for row #1 (Ultra-curb guard). Remember to use your vocabulary sheet if you get stuck! 5. Now click on drain guard under the green box at the top of the page. Read about the ultra-drain guard and look at the pictures, clicking on them for enlarged images. Pay special attention to the hand drawn Schoolyard Hydro-Ecology Teachers’ Handbook - Baltimore Ecosystem Study Draft 2 – July 19, 2005 Lesson 1 - page 17 pictures of the device at the bottom of the page. Vocabulary question: One of the drain guard models has a non-leaching oil absorbent pillow. What does this mean? 6. Using words and/or pictures, explain what this device does and how it works. 7. On the attached chart, fill in the information for row #2 (Ultra-drain guard). 8. Now type the address “www.bestmp.com” into your browser. A picture of “The SNOUT” should come up. Click on “How the SNOUT oil-waterdebris separator works.” Study the diagram. Vocabulary question: Would you describe this device as a retrofit? Why? 9. Describe how the SNOUT works using words and/or pictures. 10. On the attached chart, fill in the information for row #3 (The SNOUT). Schoolyard Hydro-Ecology Teachers’ Handbook - Baltimore Ecosystem Study Draft 2 – July 19, 2005 Lesson 1 - page 18 11. Now type “www.freshcreek.com/products/prod_specs.php?prodID=floating” into your browser. Study the information on the floating netting trash trap. Click on the drawing to enlarge. Vocabulary question: Does this device catch primarily non-point source or point-source pollutants? 12. Using words and/or pictures, describe how this device works. 13. On the attached chart, fill in the information for row #4. 14. Now that you have completed the chart for some devices already in place, think about what you would like the features of your invention to be. Fill out row #5 with this information, and use this to brainstorm about what your device will look like. If you have more than one idea, fill out another row beneath row #5. Schoolyard Hydro-Ecology Teachers’ Handbook - Baltimore Ecosystem Study Draft 2 – July 19, 2005 Lesson 1 - page 19 Part II: Now that you are an expert on storm drains, it’s time to design your own pollution catchment device. You now have at your access tons of information from your storm drain vocabulary sheet, your internet research, and your in-class activities with your Living Classrooms Foundation teachers. So put on your thinking caps and let’s go! Using your research worksheets and creative ideas, design your own device for preventing pollution from entering our waterways via storm drains. In addition to a drawing, or “blueprint”, of your device, you should write a twoparagraph article. The first paragraph should include specific information about your invention. How does it work? Where is it installed (infall or outfall)? On what types of land use would it be most effective (residential, schoolyards, businesses, construction sites)? What materials are required to build it? The second paragraph should include the benefits of your design, as well as concerns about potential problems. What are the costs to build it? What are the costs to maintain it? Does it catch a wide range of pollutants (sediment, litter, oil, vegetation) or does it target just a few? Use these questions to guide your writing, but be sure to include any additional information that helps the reader understand why your design is desirable. Remember this is your device, so think hard and be creative. Good luck! School Leadership in Urban Runoff Reduction Project Schoolyard Hydro-Ecology Teachers’ Handbook - Baltimore Ecosystem Study Draft 2 – July 19, 2005 Lesson 1 - page 20 Lesson 1 – Urban, Schoolyard and Home Hydrology Student Handout: Storm Drain Vocabulary Use this vocabulary list to help you understand the storm water management devices you will be looking at on the web to complete this activity. BMP or Best Management Practice- activities or structural improvements that help reduce the quantity and improve the quality of storm water runoff Boom- a floating device used to contain oil or floating debris on a body of water Catch Basin- an entryway to the storm drain system, usually located at street corners and the bottoms of hills Catchment Device- a device installed at some location in the storm drain network designed to trap litter, sediment, and/or oil before it enters the watershed. Contaminant- a substance that adds impurities Debris- carelessly discarded refuse; litter Erosion- the group of natural processes, including weathering, dissolution, abrasion, corrosion, and transportation by which material is worn away from the earth’s surface Exert- when referring to an infall catchment device, a screen or grate placed on top of a storm drain catch basin to prevent litter and vegetation from being washed into the storm drain by storm water Schoolyard Hydro-Ecology Teachers’ Handbook - Baltimore Ecosystem Study Draft 2 – July 19, 2005 Lesson 1 - page 21 Infall- a place where water enters the storm drain network, including curb inlet storm drains and flat grate storm drains Insert- when referring to an infall catchment device, a device placed inside a storm drain catch basin to prevent litter, vegetation, oil, and sediment from entering the watershed. Leach- to dissolve or pull out a substance by passing liquid through a permeable solid (you make coffee by allowing hot water to leach flavor out of coffee grounds) Low impact development- the practice of using techniques in building and construction that minimize the effect that development will have on the quality of the surrounding environment. Non-Point Source (NPS) Pollutants- Pollutants from many diffuse sources. Rainfall or snowmelt moving over and through the ground causes NPS pollution. As the runoff moves, it picks up and carries away natural and human-made pollutants, finally depositing them into lakes, rivers, wetlands, coastal waters, and even our underground sources of drinking water. Outfall- a place where a pipe carrying storm water from storm drains empties into a stream. Point Source Pollutant: Pollutants from a single, identifiable source such as a factory, refinery, or place of business. Retrofit- to fit into or onto equipment already in existence or service Storm Water Management- practices developed in an attempt to reduce the negative impacts of storm water on stream and watershed health Schoolyard Hydro-Ecology Teachers’ Handbook - Baltimore Ecosystem Study Draft 2 – July 19, 2005 Lesson 1 - page 22 Sump- A pit or tank that catches liquid runoff for drainage or disposal Watershed- The whole region or extent of land which contributes to the supply of a river, lake, or other body of water. Additional Resources If you’re stuck or would just like more information, try consulting these websites: • www.ulct.org/apwa/Glossary.htm: an extended glossary of storm water vocabulary. • www.forester.net/sw_glossary.html: another glossary. • www.dnr.state.md.us/bay/tribstrat/nps_pollution.html: a good source of info on non-point source pollution and easy ways citizens can reduce their contribution to storm water runoff pollution. OR Type combinations of any of the following words into a search engine (google.com, ask.com) to generate a list of web pages on the topic: • stormwater, runoff, management, pollution, stormdrain, catchment School Leadership in Urban Runoff Reduction Project Schoolyard Hydro-Ecology Teachers’ Handbook - Baltimore Ecosystem Study Draft 2 – July 19, 2005 Lesson 1 - page 23 Lesson 1 – Urban, Schoolyard and Home Hydrology Student Lesson: Creating Your Storm Drain Stenciling Brochure A brochure is an inexpensive yet effective tool people use to dispense information. They can be used to advertise, educate, persuade, or inform. Brochures are usually made of pieces of paper folded twice in order to organize the space into different sections. You will be making a brochure informing your community of our upcoming storm drain stenciling project and educating them about how runoff pollution reaches the Chesapeake Bay through storm drains. That is a lot to cover on a small piece of paper, so we will go step by step through the information that should be included in each section. Once you complete this worksheet, write the information, IN YOUR OWN WORDS, onto the attached brochure template. Add any drawings or diagrams that you think will make your brochure more powerful and helpful. Your brochure, like most brochures, will look like this: Let’s go through the pages as they are numbered above one at a time and think about what should be included on each. Certain information will need to be on everyone’s brochure. This information is already printed on the appropriate pages for you. Page 1: Title Page When creating the title of the brochure, be clear and succinct (not too wordy). You want to get your readers attention without making them read a long sentence. Reread the first paragraph on this page. What is the topic of this brochure? ________________________________ You might want your title to be straight forward, or you might want it to be catchy. Don’t be afraid to be creative! Once you come up with your title, write it onto page 1 either above or below the box. Use the space inside the box to draw a picture that you think will help make the subject of the brochure more clear to the reader. Page 2: Introduction This is probably the first page the reader will look at when he or she opens the brochure up. That makes this an ideal place for you to introduce the purpose of the brochure and outline any background information they will need to know in order to understand the rest of the brochure. If you can answer the following questions, you are well on your way to writing a good introduction. What is the purpose of this brochure? (hint: there are two, look for them in the first paragraph on this page) Schoolyard Hydro-Ecology Teachers’ Handbook - Baltimore Ecosystem Study Draft 2 – July 19, 2005 Lesson 1 - page 24 _________________________________________________________ Who is your audience? _______________________ This brochure is about something that we will be doing in your community to help fix a problem. What is the problem we are trying to fix? Be specific. ______________________________________________________________ Why should the reader care? __________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ After you have answered these questions, use your answers and any other ideas you want to include to write an organized paragraph that will serve as your introduction. Copy it into the brochure on page 2, adding any graphics you see fit. Page 3: The Specifics So far we’ve told the reader that there is a problem that we feel needs to be addressed, now let’s tell them what is going to be done about it. This page should give details about the main idea of the brochure. Use the following questions to help you think of information that should be included here. What are we doing to help correct the problem we talked about in the introduction? __________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ How will this help? __________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ When will we be doing it? ________________________________________ Where will we be doing it? _______________________________________ How can the reader get involved? ______________________________________________________________ What other information should the public know? __________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ Once you’ve assembled this information, write it onto page 3. It doesn’t need to be in paragraph form, but make sure it is organized so that it is easy to understand and you like how it looks! Page 4: Facts Schoolyard Hydro-Ecology Teachers’ Handbook - Baltimore Ecosystem Study Draft 2 – July 19, 2005 Lesson 1 - page 25 Hopefully your audience will be interested by this point and will want to know more information. Use this page to list any facts that might answer further questions the reader may have or convince them of the importance of this project. Think about what you have learned from the activities you have done with the Living Classrooms Foundation teachers (the runoff model, the water cycle, the history mystery), and what facts about the topic struck you as interesting or made you want to learn more. Use the space below to brainstorm and create a list of facts you might want to include. If your having trouble, use the questions on the next page to help you. The answers to any of those questions would make great facts to include in your brochure. Choose your three favorites (or more!) and write these facts on page 4 of your brochure. __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ Page 5: Partners Whether you know it or not, there are a lot of organizations involved in bringing this project to your school. This page lists them in case the reader is interested in finding out more about related projects. It’s like the credits after a movie! These organizations include: the Living Classrooms Foundation, Baltimore City Public Schools, the Parks and People Foundation, the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the Department of Recreation and Parks, and the City of Baltimore. Look them up to find out what these organizations are all about! Just the facts, ma’am: Use this list of questions to help you come up with facts to be included on page 4 of your brochure. How does the type of things we put on our land (roads, buildings, gardens, etc.) affect the quality and quantity of our runoff? What is a watershed? Schoolyard Hydro-Ecology Teachers’ Handbook - Baltimore Ecosystem Study Draft 2 – July 19, 2005 Lesson 1 - page 26 Do you have to live right next door to the Bay to have and affect on its health? Explain. How has Baltimore’s landscape changed throughout history? How does this affect the runoff coming from the city? What is the biggest source of pollution to the Chesapeake Bay? Does water go to the same place after it flows into storm drains as it does after it flows down your sink drain? School Leadership in Urban Runoff Reduction Project Schoolyard Hydro-Ecology Teachers’ Handbook - Baltimore Ecosystem Study Draft 2 – July 19, 2005 Lesson 1 - page 27