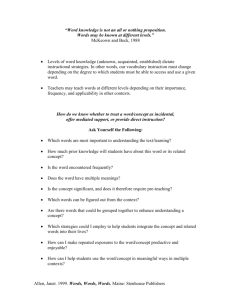

pre-teaching math language lessons for

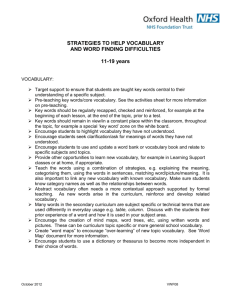

advertisement