10-27-2013 Accidentally on Purpose_Layout 1

advertisement

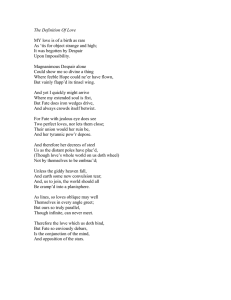

Accidentally on Purpose Sara Goodman October 26, 2013 Readings “The Riddles of Hamlet,” Simon Augustine Blackmore I t is strictly and philosophically true that there is no such thing as chance or accident; since these words do not signify anything really existing, anything that is truly an agent or the cause of any event; but they merely signify man’s ignorance of the real and immediate cause. Most tragic events turn on most trifling circumstances. [In Shakespeare’s work,] The fate of Richard II, is traced to a momentary impulse—an impulse that cost him his kingdom and his life. Poor Desdemona’s fate hangs on the accidental dropping of a handkerchief. The unhappy death of Romeo and Juliet result from the miscarriage of a letter. The noble Caesar would not have met his untimely death, had he not postponed reading the schedule of Artemidorus. Wolsey fell from the full meridian of his glory by a slight inadvertence, which all his deep sagacity could not redeem. But of all the poet’s plays, the predominance of chance over human designs is most powerfully brought home in the tragedy wherein the fate of Hamlet turns on accident after accident. These fortuitous events are variously denominated, as Destiny, or Fate, or Chance; but, in the poetical religion of Shakespeare, they are recognized as the direction of a Providence that exercises supreme control over human affairs. From Conversations with God, Neale Donald Walsch God: Yet know this: there is no such thing as an incorrect path—for on this journey you cannot “not get” where you are going. Neale: Then what is the point? If there is no way not to “get there,” what is the point of life? Why should we worry about anything we do? God: Well, of course, you shouldn’t [worry]. But you would do well to be observant. Simply notice who and what you are being, doing, and having, and see whether it serves you. The point of life is not to get anywhere—it is to notice that you are, and have always been, already there. You are, always and forever, in the moment of pure creation. The point of life is therefore to create—who and what you are—and then to experience that. Neale: And what of suffering? Is suffering the way and the path to God? Some say it is the only way. God: I am not pleased by suffering, and whoever says I am does not know Me. Suffering is an unnecessary aspect of the human experience. It is not only unnecessary, it is unwise, uncomfortable, and hazardous to your health. Neale: Then why is there so much suffering? Why don’t you, if you are God, put an end to it if you dislike it so much? God: I have put an end to it. You simply refuse to use the tools that I have given you with which to realize that. You see, suffering has nothing to do with events, but with one’s reaction to them. What’s happening is merely what’s happening. How you feel about it is another matter. I have given you the tools with which to respond and react to events in a way that reduces—in fact, eliminates—pain, but you have not used them. Neale: Excuse me, but why not eliminate the events [that cause us suffering]? God: A very good suggestion. Unfortunately, I have no control over them. Neale: You have no control over events? God: Of course not. Events are occurrences in time and space that you produce out of choice— and I will never interfere with choices. To do so would be to obviate the very reason I created you. But I’ve explained this all before. Some events you produce willfully, and some events you draw to you—more or less unconsciously. Some events—major natural disasters are among those you toss into this category—are written off to “fate.” Yet even “fate” can be an acronym for “from all thoughts everywhere.” In other words, the consciousness of the planet. Neale: The “collective consciousness.” God: Precisely. Reflections ccidentally on purpose is a delightful phrase that I found while reading novels. It has been around for centuries and is a funny little oxymoron. It means doing something “on accident” with quotes around it—in other words I am intending to make this look like an accident, or I am intentionally getting in a situation where I know an accident could happen. A Accidentally on Purpose, by Sara Goodman, October 27, 2013 back to Greek philosophy. In Greek and Roman mythology, fate is described as “the three fates”—three women, sometimes depicted as Maiden- Mother- Crone, who have control of the destiny of all beings, including the most powerful Gods. The youngest, the maiden, spins the wool of a life force into a thread that she feeds to mother, who measures the thread, before passing it to the crone, who then cuts the thread to the chosen length. The length of every life is predetermined before every person is born. I love the image of these three women working together with their hands on all parts of a life—there in the forming, in the living of the life, and in the cutting off from living. In Shakespeare, these three fates are reimagined, often called the three witches, as the women who direct the fate of Macbeth. The famous phrase of the witches, “toil toil, boil and bubble” comes from these women, who told the unfortunate future ruler only part of his fortune. More common in Shakespeare’s plays is the idea that fate is written in the stars, and when we try to control our destiny bad things happen. The idea that God had predestined everything in people’s lives was generally accepted in this post-reformation, Christian country. However, many people still believed in the concept of the wheel of fortune. The turning of this wheel could bring the most fortunate person low and the lowliest person into great fortune, but it was unpredictable where you would land. It was a way to describe the twists of fate that could happen to people in their lifetimes. As we heard in our reading, Blackmore believed that Shakespeare’s characters fell victim to twists of fate’s wheel that only appeared to be accidents. They were no accidents, though; this was the way it was going to unfold all along. Blackmore clarifies, saying, One of my favorite authors, Jennifer Crusie, used it to describe her lead character’s behavior in at least three of her novels. In one of Crusie’s books, Mab, an artist working on repairing a fortune telling machine, “accidentally on purpose” hits the lever multiple times, so she can get more fortunes without looking like she is interested in reading them. You see, she doesn’t believe in silly things like fate, fortune telling, or magic, but she is drawn to them all the same. Many of us feel the same way. Perhaps to you the world is too clearly logical to believe in fate, destiny, or predestination, and yet you find yourself saying something like “it was meant to be” when something good happens. Or maybe you find the small coincidences in your life to be something more than accidents, but somehow you can’t put your finger on why. So we go along in our lives making little accidents happen, maybe on purpose, or maybe unintentionally. Have you dropped something to distract someone from something you didn’t want them to see? Have you picked up the phone to call your mom and accidentally called a friend’s number instead—only to find out that your friend really needed to hear from you that day? Were these accidents or done on purpose? I think “on-purpose accidents” are typically self-serving: we create an accident to make ourselves look better in another’s eyes. Be it distracting them from something we don’t want them to see or trying to hide our true intentions—like caring too much about something that’s socially unacceptable or feeling vulnerable and needy. Maybe we make purposeful accidents because we want to connect with people—we want to be accepted and maybe even loved. But maybe we don’t know why we do what we do. Jung is famous for saying “Until you make the unconscious conscious, it will direct your life, and you will call it fate.” So, is it our unconsciousness that drives us, or is it something more? OK, so what is fate anyway? Fate is a big idea word—what the heck does it mean? Traditionally fate has been described as the plan that has been set out for our lives. Be it God, the universe, or some indescribable force in the world, the course of our lives has been set for us before we were ever born. Many of us may immediately think of the Calvinist idea of predestination—it has already be decided if we are going to heaven before we are even born—but Fate as an idea goes way These fortuitous events are variously denominated, as Destiny, or Fate, or Chance; but in the poetical religion of Shakespeare, they are recognized as the direction of a Providence that exercises supreme control over human affairs. This idea of providence is what I like to call the Abrahamic view of fate as influenced by the biblical traditions. This is the plan of a life chosen and overseen by the all-powerful father figure. Last week, Michael spoke at length about this concept of fate and how it has lost meaning for many people, most especially the existentialists. They mainly 2 Accidentally on Purpose, by Sara Goodman, October 27, 2013 Process thought doesn’t believe that what will be is set out or that there is an omnipotent (all powerful) being out there that can force any behavior or outcome. The belief is that there is a divine lure toward expansion, toward progress—not necessarily towards good or away from evil. We have free will to respond to this lure, or not. For me, I imagine this lure as this stream of energy that moves through us all at varying speeds. We have control over the tap in our soul—we can turn the faucet either direction—towards an open tap with a rushing stream of life force or towards a closed tap with just a few drops coming through. No matter what, the life force is moving through us luring us towards opening the tap more, but we can always turn away from this lure. I think our feelings are our guide in this, when we feel good we are allowing the energy to flow, and when we feel bad, we are steming the flow. So, what does this mean for how I live my life? I am constantly looking for thoughts that feel better—that feel like relief of suffering. Not happiness really, but relief. Conversations with God is a series of books that were popular in the ’90s and that chronicle the conversation that the author, Neale Donald Walsch, had with what he believes to be God, but what I would call the universe. You may translate the name God in a different way. In the earlier reading, Walsch has asked God what the point of life is, if there is no end goal. God responds, “The point of life is not to get anywhere—it is to notice that you are, and have always been, already there. You are, always and forever, in the moment of pure creation. The point of life is therefore to create who and what you are and then to experience that.” The point of life is to experience creation. But Walsch goes on to ask a question that may be on your minds as well. What about bad things? Why do bad things happen? It’s all well and good to say that the universe lures us towards expansion, but what about the people who experience terrible suffering? God responds: “You see, suffering has nothing to do with events, but with one’s reaction to them. What’s happening is merely what’s happening. How you feel about it is another matter.” So, suffering is about emotional attachment to outcomes. This is one of the key Buddhist teachings. Attachment is suffering. Let me tell you a story. This story comes from the Taoist tradition out of China. believe that there is no purpose to life but living. In stark contrast is the belief in karma and reincarnation in Hinduism and Buddhism. In both religions, the primary purpose of living life is to be free from living—to stop being reincarnated. OK, so that is a simplistic and incomplete description of the beliefs and practices of Hinduism and Buddhism. But it doesn’t negate the fact that the belief is that our lives are free to be lived with choice and freedom, but that the only way to stop the cycle of birth and rebirth is to reach a sufficient level of detachment from life. According to some Hindu traditions, there are two kinds of karma. One is the commonly known, “bad karma,” which is described as an iron chain, and the other is “good karma” which is a golden chain. Both keep you in the cycle of reincarnation, one with misdeeds, bringing you down the hierarchy, and the other bringing you up the ladder. But until you can be free of your emotional attachment to the good things you have done, you will never be free of the chain. In a way, reincarnation has a level of predestination as well. If you are born into a low station in life, it is believed that you had an accumulation of “bad karma,” a weight of the iron chain brought with you from a former life. The difference is that you can change the outcome of your life, and the outcome of your next life by living with intention and accumulating “good karma.” In this way, all that has come before is incorporated into the present moment. This idea resonates with my soul; the idea that all that has come before this moment influences this moment. But I see it as much broader than my individual life. I believe that the universe works in this way. I’ve had a sort of metaphysical/quantum physical view of the world for a while now. I feel like there is more to the universe than can be explained, and if there is a God, it is made up of all that we see, feel, and do in the world. This is most clearly stated by process philosopher Alfred North Whitehead in his seminal work Process and Reality, written in 1927. He posits, “It is as true to say that God creates the world, as that the world creates God.” According to Whitehead, the universe (or God if that name works for you) is as much creator of us as we are of it. All-that-is or has ever been is a part of a living creativity. Every moment all-that-is expands to include all new experience that’s happening in the current moment, becoming greater for the experience. [There once was] A man who lived on the northern frontier of China. He was skilled in 3 Accidentally on Purpose, by Sara Goodman, October 27, 2013 through space. There is a shiny “spear” of energy that leads each person to what he or she will do next. His own “spear” appears, and it beckons him forward. He believes that this is his fate, and he has no choice but to follow. Donnie rushes to speak to his science teacher about what he’s seen. He believes that he can see the pre-decided path that God has set for each person and that if he can see that, he can see into the future. He asks if this is time travel, and his teacher responds: interpreting events. One day, for no reason, his son’s horse ran away to the nomads across the border. Everyone tried to console him, but his father said, “What makes you so sure this isn’t a blessing?” Some months later, his horse returned, bringing a splendid nomad stallion. Everyone congratulated him, but his father said, “What makes you so sure this isn’t a disaster?” Their household was richer by a fine horse, which his son loved to ride. One day he fell and broke his hip. Everyone tried to console him, but his father said, “What makes you so sure this isn’t a blessing?” A year later, the nomads came in force across the border, and every able-bodied man took his bow and went into battle. The Chinese frontiersmen lost nine of every ten men. Only because the son was [injured] did the father and son survive to take care of each other. Truly, blessing turns to disaster, and disaster to blessing: the changes have no end, nor can the mystery be fathomed.” How can we know what will be a blessing, and what will be a disaster? You’re contradicting yourself, Donnie. If we could see our destines manifest themselves visually... then we would be given the choice to betray our chosen destinies. The very fact that this choice exists... would mean that all pre-formed destiny would end.” But Donnie argues, “Not if you chose to stay within God’s channel. . . . ” This conversation sums up the core message of this movie. If you knew what the future was going to bring you, and it wasn’t what you were hoping for, would you live out that destiny? On the night of Halloween, Donnie eventually sets into motion a series of events that end in the deaths of two people, including his girlfriend, and the imminent death of his mother and sister. He realizes when the time comes, that to save the people he loves he needs to travel back in time to die in his bed when the jet engine crashes into it. On the morning of his death all the people affected by what has happened in those 28 days wake up from the same dream; the dream of what could happen if they keep living the way they are living, what could happen if they ignore the lure of the universe. So what would you do? How would you choose to live your life if you could see the future? Would you be defeated, resigned to living the life given to you? Would you embrace it, moving towards your destiny with relish? Would you try to change the outcome? No matter how you believe the world to be— predestined, chaotic, luring you towards expansion, you have to live in the world. I truly believe that having a full enjoyable life means living as if you have control over your destiny. We need to believe that our choices make a difference in our lives. You’ve got to live life, to experience it fully, in order to get the most out of it. So do your best to live a purposeful life despite the accidents that come your way. Maybe that is our destiny. This point is illustrated by one of my favorite Halloween movies, Donnie Darko. It is a little known film but was a cult hit for my generation. This independent movie, released in 2001, is a dark psychological thriller set in 1988. Donnie Darko is a suburban teen with self-proclaimed emotional problems. One night he is awakened by Frank, a six-foot-tall bunny rabbit, who lures him out of bed to tell him that the world will end in 28 days on Halloween, and he is the only one who can save it. When Donnie comes home the next morning, he discovers that a mysterious jet engine has crashed through the roof of his bedroom. If he had been in bed, he would have died. At first, this seems like amazing good fortune, but with the series of awful things that follow it’s clearly a disaster. In the course of the movie, Donnie is visited repeatedly by Frank who tells him to do increasingly destructive things, including flooding his high school, and burning down someone’s house. He also tells Donnie to find out more about time travel. Donnie talks to his science teacher about Steven Hawking’s book A Brief History of Time and the science teacher gives him a book by a local female scientist called The Philosophy of Time Travel. Soon he starts to see the path of people as they travel CWL 4