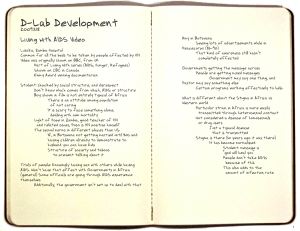

Interventions to Reduce HIV and AIDS Stigma

advertisement