Trauma, Memory, and Therapy: Reconstructing the Past

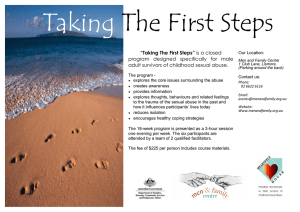

advertisement