Issues in Emerging Health Technologies

advertisement

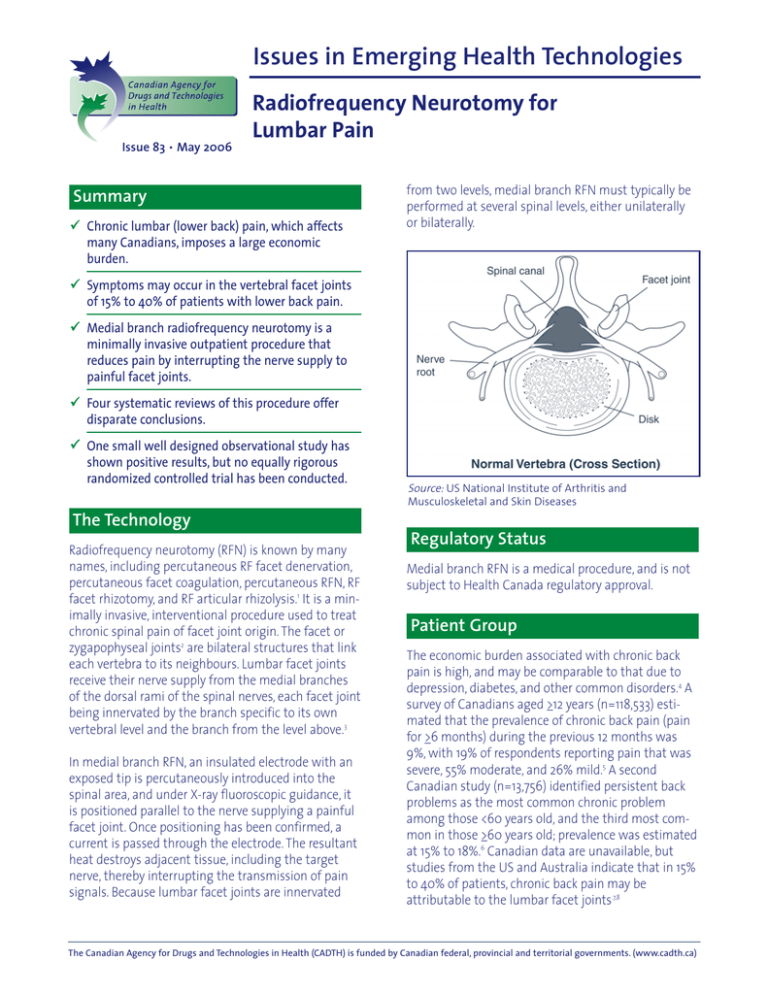

Issues in Emerging Health Technologies Issue 83 • May 2006 Radiofrequency Neurotomy for Lumbar Pain Summary Chronic lumbar (lower back) pain, which affects many Canadians, imposes a large economic burden. from two levels, medial branch RFN must typically be performed at several spinal levels, either unilaterally or bilaterally. Symptoms may occur in the vertebral facet joints of 15% to 40% of patients with lower back pain. Medial branch radiofrequency neurotomy is a minimally invasive outpatient procedure that reduces pain by interrupting the nerve supply to painful facet joints. Four systematic reviews of this procedure offer disparate conclusions. One small well designed observational study has shown positive results, but no equally rigorous randomized controlled trial has been conducted. Source: US National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases The Technology Radiofrequency neurotomy (RFN) is known by many names, including percutaneous RF facet denervation, percutaneous facet coagulation, percutaneous RFN, RF facet rhizotomy, and RF articular rhizolysis.1 It is a minimally invasive, interventional procedure used to treat chronic spinal pain of facet joint origin. The facet or zygapophyseal joints2 are bilateral structures that link each vertebra to its neighbours. Lumbar facet joints receive their nerve supply from the medial branches of the dorsal rami of the spinal nerves, each facet joint being innervated by the branch specific to its own vertebral level and the branch from the level above.3 In medial branch RFN, an insulated electrode with an exposed tip is percutaneously introduced into the spinal area, and under X-ray fluoroscopic guidance, it is positioned parallel to the nerve supplying a painful facet joint. Once positioning has been confirmed, a current is passed through the electrode. The resultant heat destroys adjacent tissue, including the target nerve, thereby interrupting the transmission of pain signals. Because lumbar facet joints are innervated Regulatory Status Medial branch RFN is a medical procedure, and is not subject to Health Canada regulatory approval. Patient Group The economic burden associated with chronic back pain is high, and may be comparable to that due to depression, diabetes, and other common disorders.4 A survey of Canadians aged >12 years (n=118,533) estimated that the prevalence of chronic back pain (pain for >6 months) during the previous 12 months was 9%, with 19% of respondents reporting pain that was severe, 55% moderate, and 26% mild.5 A second Canadian study (n=13,756) identified persistent back problems as the most common chronic problem among those <60 years old, and the third most common in those >60 years old; prevalence was estimated at 15% to 18%.6 Canadian data are unavailable, but studies from the US and Australia indicate that in 15% to 40% of patients, chronic back pain may be attributable to the lumbar facet joints.7,8 The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) is funded by Canadian federal, provincial and territorial governments. (www.cadth.ca) The only valid and reliable diagnostic test for facet joint pain is fluoroscopically guided, controlled diagnostic medial branch blocks, or intra-articular facet joint blocks.2,7,9-12 Patients who are unresponsive to conservative therapy and who have positive pain relief from controlled diagnostic blocks may be suitable for medial branch RFN. Current Practice Conservative treatments for chronic lumbar pain include exercise, oral medications, physical therapy, spinal manipulation, and behavioural therapy. Most have, at best, modest efficacy.13,14 Interventional therapies for facet joint pain include intra-articular facet joint injections, medial branch nerve blocks, and medial branch RFN.11,12 No accurate utilization data are available for these procedures. However, the use of medial branch RFN is relatively uncommon in Canada (Dr. D. Vincent, Victoria, BC: personal communication, 2006 Mar 02). The Evidence Four systematic reviews (SRs) address the efficacy of medial branch RFN for lumbar facet joint pain.15-18 Two15,17 include only randomized controlled trials (RCTs), while the others16,18 include RCTs and observational studies. The SRs reach divergent conclusions: • Geurts et al.15 found moderate evidence that the procedure is more effective than placebo. • Manchikanti et al.16 found strong evidence that the procedure offers short- and long-term pain relief. • Niemesto et al.17 found conflicting evidence on the short-term effect. • Boswell et al.18 found moderate to strong evidence in favour of efficacy. The SRs include four relevant RCTs19-22 and six observational studies.8,13,23-26 Most of the included studies relied on single diagnostic blocks [which have a false positive rate of 27% (95% CI: 22% to 32%) in the lumbar region],7 rather than controlled diagnostic blocks in the selected patients. As a result, many enrolled patients may not have had facet joint pain. Consequently, experts such as Hooten et al. have argued that the results of several RCTs19,20,22 are invalid.27 This criticism may be applied to all the studies cited in this bulletin, with the exception of the Dreyfuss et al. study.8 In a small, well designed observational study (n=15), Dreyfuss et al. used meticulous techniques, including controlled diagnostic blocks, and they achieved significant, sustained reductions in lumbar facet pain.8 In contrast, a RCT designed to reflect common clinical practice, including reliance on single diagnostic blocks, found that medial branch RFN offered no benefit28 (Table 1). Adverse Effects Possible adverse effects (AEs) of medial branch RFN include painful cutaneous dysesthesias, neuritis or neurogenic inflammation pain, anesthesia dolorosa, cutaneous hyperesthesia, pneumothorax, and deafferentation pain.11,12 AEs reported in two studies23,28 included treatment-related pain, transient neuropathic pain, transient leg pain, dysesthesia, and subjective leg weakness; the other studies reported no AEs. One centre performing lumbar medial branch RFN estimated the incidence of minor AEs at 1% per lesion site.29 Administration and Cost Historically, medial branch RFN was a neurosurgical procedure, but currently, anesthetists and other physicians specializing in pain medicine perform it most often.9 The time required depends on the number of levels to be treated, but estimates range from 20 minutes (most likely) to five hours.30 Local anesthesia is generally used, although general anesthesia may be preferred in some centres.23 The procedure can be repeated at three-month intervals if >50% pain relief is obtained for 10 to 12 weeks post-RFN.11,12 Payment may come from provincial health plans or third-party payers such as workers’ compensation boards. No cost-effectiveness evaluations were located, and little costing data are available.11,12 A 2001 Canadian review addressing medial branch RFN for cervical facet joint pain estimated the procedural cost at C$401, excluding physician fees, the cost of diagnostic blocks, and overhead costs (e.g., RF neurotomy needles, RF generator, fluoroscopy equipment).31 Van Wijk et al. reported total actual treatment-related costs for medial branch RFN at US$285, but details about the cost calculations are lacking.28 The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) is funded by Canadian federal, provincial and territorial governments. (www.cadth.ca) Table e 1:: Dreyfuss et al. and Van Wijk et al. studies Authorss and d Studyy Treatmentt and d Comparator Outcome e Measuress Results Dreyfuss et al.8 Texas and Australia; prospective audit with 12 months follow-up; n=15; funder was International Spinal Injection Society RFN coagulation of nerve for 8 to 10 mm (90 seconds @85C); no control group at 1.5, 3, 6, and 12 months: VAS for pain; McGill Pain Questionnaire; Roland-Morris Inventory; NASS Treatment Expectations; isometric push and pull, lift tasks, dynamic floor to waist lift, isometric above shoulder lift; electromyography of L2 to L5 multifidus bands all but lifting tasks and push-pull tasks improved significantly; 60% had 90% pain relief; 87% had 60% pain relief; scores not significantly different throughout 12-month follow-up van Wijk et al.28 the Netherlands; multicentre, randomized, double-blind, sham treatment controlled trial; n=81; funder was Dutch Health Insurance Council & Pain Expertise Center Nijmegen treatment group (n=40): RFN of medial branch of dorsal ramus (60 seconds @80C); control group (n=41): identical procedure but no RFN primary: number of successes at 3 months; secondary: GPE and SF-36 primary: number of successes in treatment group 11 (27.5%) versus 12 (29.3%) in control group (p=0.86); secondary: only GPE showed significant difference in favour of treatment group GPE=global perceived effect; NASS=North American Spine Society; RFN=radiofrequency neurotomy; SF-36=Short Form 36; VAS=visual analogue scale. Concurrent Development While there are some practitioners who advocate the use of pulsed rather than continuous RF current, this is a modification of the existing technique.32 One study that was identified recommends intra-articular (in the joint) RFN rather than medial branch RFN.21 Rate of Technology Diffusion The diffusion of medial branch RFN in Canada is unknown. Demand may increase because of its perceived success compared with many conservative therapies, and because of the social and personal costs of unresolved chronic back pain. The limited number of physicians practising interventional pain management techniques is likely to restrict availability. research inconclusive. The most rigorous assessment to date suggests that meticulous attention to diagnosis and treatment may generate positive results,8 but this was extracted from a small observational study, and equally rigorous RCTs have yet to be conducted. Medial branch RFN is a specialized procedure. Physicians must place an electrode, depending on its size, within a millimetre of the target nerve to successfully interrupt the nerve supply to the facet joint. The contrast between the study results of Dreyfuss et al.8 and Van Wijk et al.28 may highlight the importance of training, and the need for practice guidelines related to medial branch RFN. References 1. Cigna healthcare coverage position: radiofrequency ablation for chronic spinal pain. Atlanta: CIGNA; 2005. Available: http://www.cigna.com/health/provider/medical/procedural/coverage_positions/medical/mm_0144_coveragepositioncriteria_radiofrequency_ablation_for_chro nic_spinal_pain.pdf. 2. Manchikanti L. Curr Rev Pain 1999;3(5):348-58 3. Lumbar radiofrequency neurotomy for chronic zygapophysialJoint pain: a pilot study using dual medial branch blocks. I S I S Sci Newsl 1999;3(2). Available: http://www.spinalinjection.com/a/newsltrs/Feb1999.pdf. Implementation Issues Almost 30 years have passed since the first reports about medial branch RFN were published, yet the procedure has not gained uptake, and remains an emerging technology.17 Some studies suggest that medial branch RFN is efficacious, but procedural and other methodological shortcomings render much of this The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) is funded by Canadian federal, provincial and territorial governments. (www.cadth.ca) 4. Maetzel A, et al. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2002;16(1):23-30 28. van Wijk RM, et al. Clin J Pain 2005;21(4):335-44 5. Currie SR, et al. Pain 2004;107(1-2):54-60 30. Curatolo M, et al. Spine 2005;30(2):263-5 6. Rapoport J, et al. Chronic Dis Can 2004;25(1):13-21. Available: http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/cdicmcc/25-1/c_e.html. 31. 7. Manchikanti L, et al. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2004;5:15. Available: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2474/5/15. 8. Dreyfuss P, et al. Spine 2000;25(10):1270-7 9. Lord SM, et al. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2002;16(4):597-617 29. Kornick C, et al. Spine 2004;29(12):1352-4 Bassett K, et al. Percutaneous radio-frequency neurotomy treatment of chronic cervical pain following whiplash injury:reviewing evidence and needs. Vancouver: BC Office of Health Technology Assessment; 2001. Available: http://www.chspr.ubc.ca/bcohta/pdf/bco0105T_PRFN.pdf. 32. Mikeladze G, et al. Spine J 2003;3(5):360-2 10. Slipman CW, et al. Spine J 2003;3(4):310-6 11. Manchikanti L, et al. Pain Physician 2003;6(1):3-81. Available: http://www.asipp.org/documents/Guidelines%20200 3.pdf. 12. Boswell MV, et al. Pain Physician 2005;8(1):1-47 13. Vad VB, et al. Pain Physician 2003;6(3):307-12 14. Bogduk N. Med J Aust 2004;180(2):79-83. Available: http://www.mja.com.au/public/issues/180_02_190104 /bog10461_fm.pdf. 15. Geurts JW, et al. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2001;26(5):394400 16. Manchikanti L, et al. Pain Physician 2002;5(4):405-18. Available: http://www.painphysicianjournal.com/2002/october/2002;5;405-418.pdf. 17. Niemisto L, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(4):CD004058 18. Boswell MV, et al. Pain Physician 2005;8(1):101-14. Available: http://www.painphysicianjournal.com/2005/january/2005;8;101-114.pdf. 19. Gallagher J, et al. Pain Clinic 1994;7(3):193-8 20. van Kleef M, et al. Spine 1999;24(18):1937-42 21. Sanders M, et al. Pain Clinic 1999;11(4):329-35 22. Leclaire R, e al. Spine 2001;26(13):1411-6 23. Tzaan WC, et al. Can J Neurol Sci 2000;27(2):125-30. Available: http://cjns.metapress.com/media/84vpwnqqyh79l4kmexej/contributions/a/a/q/j/aaqjwkhph8jg 6pyg.pdf. 24. North RB, et al. Pain 1994;57(1):77-83 25. Schaerer JP. Int Surg 1978;63(6):53-9 26. Schofferman J, et al. Spine 2004;29(21):2471-3 27. Cite as: Murtagh J, Foerster V. Radiofrequency neurotomy for lumber pain [Issues in emerging health technologies issue 83]. Ottawa: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2006. *********************** CADTH appreciates comments from its reviewers. Reviewers: W. Mark Erwin, DC PhD, Toronto Western Hospital, Toronto ON; Daniel Denis Vincent, MD FRCPC ABDA, Vancouver Island Health Authority, Vancouver BC. This report and the French version entitled La neurotomie par radiofréquence dans le traitement des lombalgies are available on CADTH’s web site. Production of this report is made possible by financial contributions from Health Canada and the governments of Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba, New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Northwest Territories, Nova Scotia, Nunavut, Ontario, Prince Edward Island, Saskatchewan, and Yukon. The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health takes sole responsibility for the final form and content of this report. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of Health Canada or any provincial or territorial government. ISSN 1488-6324 (online) ISSN 1488-6316 (print) PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT NO. 40026386 RETURN UNDELIVERABLE CANADIAN ADDRESSES TO CANADIAN AGENCY FOR DRUGS AND TECHNOLOGIES IN HEALTH 600-865 CARLING AVENUE OTTAWA ON K1S 5S8 Hooten WM, et al. Pain Med 2005;6(2):129-38 The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) is funded by Canadian federal, provincial and territorial governments. (www.cadth.ca)