Framing, Value Words, and Citizens` Explanations of Their Issue

advertisement

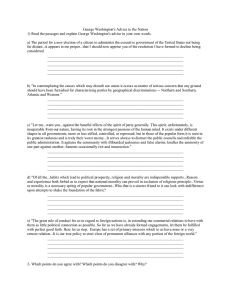

Political Communication, 19:303–316, 2002 Copyright ã 2002 Taylor & Francis 1058-4609/02 $12.00 + .00 DOI: 10.1080/01957470290055510 Framing, Value Words, and Citizens’ Explanations of Their Issue Opinions PAUL R. BREWER This study examines the effects of framing on how citizens use value language to explain their views on political issues. An experiment simulated exposure to framing in media coverage of gay rights. The results show that participants who received an “equality” frame were particularly likely to explain their views on gay rights in terms of equality and that participants who received a “morality” frame were particularly likely to cast their opinions in the language of morality. A closer examination, however, showed that exposure to the frames encouraged participants to use value language not only in ways suggested by the frames but also in ways that challenged the frames. Moreover, the results indicated that exposure to the “morality” frame interfered with the impact of the “equality” frame, suggesting that the presence of alternative frames can dampen framing effects. Keywords values, framing, public opinion, media effects, gay rights Mass media coverage of politics often contains frames that define what political controversies “are about” (Gamson & Modigliani, 1987, p. 143). Sometimes these frames use “value words” to link a particular position on an issue (e.g., pro- or anti-gay rights) to an abstract value such as equality or traditional morality (Nelson, Clawson, & Oxley, 1997; Brewer, 2001). In this study, I analyze the effects of value framing in media coverage on how citizens use value language to explain their views on political issues. Put another way, I examine whether citizens adopt the value words they find in news stories as their own words—and, if so, then how and when they go about doing so. I contribute to our understanding of framing effects in three ways. First, I provide a new and more direct test of a key assumption about the psychology of framing effects. According to several recent accounts (Kinder & Sanders, 1996; Nelson, Clawson, & Oxley, 1997), framing can influence mass opinion by shaping how citizens connect their abstract values to political issues. This claim has important implications for democratic politics; for example, if frames influence how citizens link their values to issues, then political elites may be able to shape the public’s understanding of political issues by disseminating value frames through the mass media. No study to date, however, has Paul R. Brewer is Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science, The George Washington University. Please address correspondence to Paul R. Brewer, Department of Political Science, The George Washington University, 2201 G Street, NW, Suite 507, Washington, DC 20052, USA. E-mail: pbrewer@gwu.edu 303 304 Paul R. Brewer conducted what is perhaps the most straightforward and intuitive test of whether frames shape the role of values in citizens’ thought processes: namely, testing whether frames influence how citizens explain their thoughts about an issue in their own words. In the following account, I provide such a test. Second, I provide new insights into the nature of framing effects. Research on framing typically proceeds from the assumption, implicit or explicit, that exposure to a value frame within media coverage will encourage citizens to rely on the interpretation of the value provided by that frame. Here I examine the possibility that exposure to a value frame may also encourage citizens to consider interpretations of the value that are not contained within the frame—interpretations that may even contradict the one provided by the frame. Third, I investigate whether it is possible to “fight value framing with value framing.” Most studies of framing effects have focused on establishing that such effects exist; only recently have scholars begun to delineate the circumstances under which frames will and will not produce effects (see Brewer, 2001; Druckman, 2001). I add to our understanding of the limits on framing effects by testing whether exposure to alternative value frames within media coverage can interfere with framing effects. Values, Frames, and Framing Effects A sizable body of literature, from Rokeach (1973) onward, has shown that Americans use their values to form issue opinions. While much of this research (e.g., Hurwitz & Peffley, 1987; Feldman, 1988) has analyzed closed-ended opinion measures (i.e., measures that provide defined response options), there are important exceptions. Hochschild (1981) and Feldman and Zaller (1992), for example, use open-ended measures (i.e., measures that allow respondents to express views in their own words) to show that citizens base their political views on multiple values rather than relying on just one principle to define the political world. One implication of this research is that a person may hold two values that pull in opposite directions within a particular issue domain (see also Tetlock, 1986; Alvarez & Brehm, 1995). Given that citizens can often use competing values to make sense of issues, how do they choose among their values? According to the framing literature, citizens can rely on the frames they receive from the mass media in deciding which value or values to connect to specific issues (Kinder & Sanders, 1996; Nelson, Clawson, & Oxley, 1997; Koch, 1998). In particular, they can draw on value frames, which define the “correct” position on an issue in terms of an abstract value (Brewer, 2001). Studies of framing and public opinion offer two alternative psychological explanations for why exposure to value frames in mass media coverage might influence how people link their values to issues. Some studies of framing effects argue that such exposure primes values in citizens’ memories, thereby making them easier to recall when citizens are asked to express their views (Zaller, 1992; Kinder & Sanders, 1996). Put another way, a frame can alter the accessibility of a value in the receiver’s mind. Other studies conclude that framing effects emerge because framing influences the importance that citizens attach to their values (Nelson, Clawson, & Oxley, 1997; Nelson, Oxley, & Clawson, 1997; Nelson & Oxley, 1999). According to this view, exposure to a frame can lead citizens to assign greater weight or relevance to a value invoked by the frame. Although they differ in their particulars, each account leads to the same basic expectation: Exposure to a frame that emphasizes a specific value should magnify the role of that value in citizens’ thought processes. Framing, Value Words, and Explanations 305 Several recent experimental studies have inferred evidence of such effects from closed-ended measures of values and opinions. For example, Kinder and Sanders (1996) conclude from the results of an experiment in survey question wording that the effects of values on opinion can differ depending on which frame is included in the question. Similarly, Nelson, Clawson, and Oxley (1997) draw on laboratory experiments in arguing that the effects of values on issue opinions can be altered by exposure to frames embedded in television news broadcasts and electronic newspaper articles. Yet, the closedended measures that these authors employ to measure citizens’ values and issue opinions provide only indirect and incomplete information about the thought processes by which citizens connect the two. By looking at how citizens use their own words to describe what they were thinking after being presented with value frames, we may discover previously unrecognized complexity in the nature of framing effects. How might exposure to value framing shape the content of citizens’ open-ended responses? Previous theoretical accounts of framing imply that such exposure should influence whether citizens use the language of values to explain their opinions on political issues. If exposure to a value frame makes the value invoked by that frame more accessible in citizens’ memories (Zaller, 1992; Kinder & Sanders, 1996), then people who receive the frame should be especially likely to recall the value when they search for words to express their thoughts on the issue. Likewise, if exposure to a value frame leads citizens to assign greater weight in their judgments to the value invoked by that frame (Nelson, Clawson, & Oxley, 1997), then such exposure should lead them to assign it greater weight in their explanations as well. Either way, if media coverage emphasizes a specific value in framing an issue, then citizens exposed to that coverage should tend to emphasize the same value when they explain their thoughts about the issue. The presence of such effects could indicate that framing is a potent tool for swaying how people think about issues: Citizens’ “own” value words may really be the words of others. Then again, the story may be more complicated than that. Although exposure to a value frame may encourage some citizens to use value language in a way that is consistent with the frame’s interpretation of the relationship between the issue and the value, it may encourage other citizens to use value language in a way that challenges this interpretation. Gamson’s (1992) focus group research suggests that citizens can draw upon popular wisdom, “counter-frames” that criticize dominant media frames, and their own reasoning skills when they encounter frames contained within media coverage. If this is so, then citizens who encounter value frames may borrow the “value words” in these frames to make their own points about an issue. I test this proposition by examining whether exposure to a value frame in media coverage encourages citizens to use value language in ways that parallel the frame’s interpretation of the value, that question the frame’s interpretation, neither, or both. Just as citizens may challenge value frames, so too may the political elites who introduce frames into public debate. The findings of Hochschild (1981) and Feldman and Zaller (1992) suggest that on many issues each side of the debate can claim at least one value in support of its position. What happens, then, when two competing value frames, each revolving around a different value, reach the public through the mass media? The literature on mass persuasion shows that exposure to competing messages can help people resist an argument (e.g., McGuire, 1969; Zaller, 1992). To date, however, there has been little research on whether the same logic applies to framing effects.1 Here I examine what happens to framing effects when citizens are exposed to two competing value frames, each revolving around a different value. 306 Paul R. Brewer Equality and Morality in the Debate Over Gay Rights In addressing these theoretical problems, I focus on the issue of gay rights. In several respects, it is an attractive test case. Not only has the controversy over gay rights received considerable media attention over the past decade; it has also been framed in terms of two core values, equality and morality (Gallagher & Bull, 1996; Wald, Button, & Rienzo, 1996; Button, Rienzo, & Wald, 1997), both of which are key components of American political culture (McClosky & Zaller, 1984). Proponents of gay rights have framed the issue with the language of equality, arguing that gay rights are equal rights (e.g., Sullivan, 1995; Vaid, 1995). Gay rights foes have framed the same issue with the language of morality, claiming that gay rights laws threaten traditional moral values (e.g., Dobson & Bauer, 1990; Robertson, 1993). These competing frames can even be found in the names of pro- and anti-gay rights organizations. For example, one anti-gay rights organization dubbed itself the Committee on Moral Concerns, while groups such as Equality Washington, the Ypsilanti Campaign for Equality, the Equality Foundation of Greater Cincinnati, Housing Opportunities Made Equal, and Prince Georgians for Equal Rights have all campaigned in favor of gay rights. Invocations of equality and morality have also appeared in the language of court decisions on gay rights. The opinions of the Colorado Supreme Court (1994) and the United States Supreme Court (1996) in the case Romer v. Evans are particularly noteworthy in this regard. Both majority opinions cite the principle of equality in ruling that an anti-gay rights ballot initiative—Amendment 2—was unconstitutional. In the Colorado Supreme Court’s majority opinion, Chief Justice Rovira states that the “right to participate equally in the political process is clearly affected by Amendment 2, because it bars gay men, lesbians, and bisexuals from having an effective voice in government” (Evans v. Romer, 1994). In the U.S. Supreme Court’s majority opinion, Justice Kennedy argues that “the principle that government and each of its parts remain open on impartial terms to all who seek its assistance” is central “both to the idea of the rule of law and our own Constitution’s guarantee of equal protection. . . . We must conclude that Amendment 2 classifies homosexuals not to further a proper legislative end but to make them unequal to everyone else” (Romer v. Evans, 1996). In his dissenting opinion to the U.S. Supreme Court decision, Justice Scalia relies on the language of morality, arguing that the true issue at hand is “moral disapproval of homosexual conduct.” According to Scalia, gays and lesbians constitute a “politically powerful minority group” whose goal to attain “full social acceptance of homosexuality” by using the legal system to reinforce their own view of morality. Thus, Amendment 2 is nothing more than a “reasonable effort to preserve traditional American moral values” (Romer v. Evans, 1996). Frames revolving around these two values have frequently appeared in mass media coverage of gay rights as well. Drawing upon a content analysis of 400 news stories about the issue that appeared from 1990 to 1997, Brewer (1999) concludes that invocations of equality and morality were prominent elements of gay rights coverage over this time period. Indeed, the most common value frame within the author’s sample linked support for gay rights to equality. To be sure, the debate over gay rights has also contained other frames (see Gallagher & Bull, 1996; Rimmerman, Wald, & Wilcox, 2000). For example, gay rights foes have cast their position in terms of “national security” and “equal rights but not special rights.” Meanwhile, gay rights supporters have invoked “fairness” and “tolerance” and have argued that “hatred is not a family value.” Still, it seems safe to say that the equality and morality frames described above have played key roles in the real-world debate over gay rights. Framing, Value Words, and Explanations 307 Hypotheses What effects might equality and morality frames exert on citizens who encounter them? First, people who receive the equality frame should be more likely than people who do not to invoke equality when they express their thoughts about gay rights in their own words. Exposure to media coverage containing this frame should make the principle of equality more accessible in their memories, more important in their judgments, or both— and thus more likely to appear in their explanations. By a similar logic, people who receive the morality frame should be more likely than people who do not to invoke morality when they explain their views on gay rights. Another question is whether exposure to these frames will lead citizens to adopt the interpretations of equality and morality that they offer, competing interpretations, neither, or both. The equality frame suggests that those who endorse equality should endorse gay rights; thus, exposure to the frame may encourage citizens to use equality language in a way that justifies gay rights policies. Similarly, exposure to the anti-gay rights morality frame may encourage citizens to invoke morality as a basis for opposing gay rights. Alternatively (or additionally), exposure to these frames could encourage citizens to discuss the implications of equality and morality in ways that challenge the pro-gay rights interpretation of equality and the anti-gay rights interpretation of morality. A final question is whether the morality and equality frames will interfere with one another. People who are exposed to the equality frame and the morality frame in conjunction with one another may be less likely to invoke equality than people who are exposed only to the equality frame. Likewise, people who are exposed to both frames may be less likely to invoke morality than people who are exposed only to the morality frame. Experimental Procedure To test these hypotheses, I conducted a laboratory experiment that simulated exposure to value frames embedded in media coverage. The experimental procedure consisted of four stages: a pretest; a treatment, which involved the presentation of one, two, or no value frames for gay rights; a distractor task; and a posttest. I recruited participants at a public university in the southeastern United States. The results presented here are based on data from the 224 undergraduate participants who completed all four stages of the experiment. My reliance on a student participant pool raises questions, of course, about the external validity of my results (Sears, 1986)—a point I revisit later. In the first stage of the experimental procedure participants completed a written pretest, presented as “a questionnaire designed to measure your opinions toward and knowledge about a variety of public figures, groups, and issues.” This pretest included items measuring opinion toward gay rights, support for equality and traditional morality, and demographic characteristics. Additional items served to disguise the specific purpose of the study. After an interval ranging from no less than 1 full week to no more than 2 months, participants completed the remaining stages of the procedure, which took place in a laboratory. Upon arrival, participants were seated at a computer and asked to follow the instructions presented on the screen. Their first task was to read four short articles “taken from real newspapers.” Each article was presented as text on the screen. The instructions introduced the first one as a “warm-up article” and explained that the other three would “all be about current political controversies.” Actually, both the first article (about the discovery of water on the moon) and the second article (about a Native American 308 Paul R. Brewer whale hunt) were included to acclimate participants to the reading task. Once they had read the practice articles, participants were presented with two additional articles—one about gay rights, the other about welfare reform. The former contained the experimental treatment that I discuss here. The computer randomized the order of the third and fourth articles so that participants had an equal chance of receiving either the gay rights or the welfare reform article first. The gay rights article (see Figure 1) was constructed from sections of actual newspaper articles. The first and last paragraphs of the article remained the same across conditions; however, I selectively edited the middle paragraphs to create a variety of Introductory Paragraph GAY RIGHTS FINDS ITS WAY ONTO BALLOTS ACROSS THE NATION From the Tampa Tribune, Oct. 4, 1998 The political cauldron of gay rights continues to boil. And as many Americans are discovering, this highly charged, divisive issue just won’t go away. The question of whether homosexuals should be protected from discrimination keeps popping up on the ballot across the nation. So far, eight states and about 130 cities and counties have adopted laws protecting gays and lesbians from discrimination. Opponents of gay rights are responding with a two-pronged strategy. On the one hand, they attempt to repeal ordinances through local ballot initiatives. On the other, they push amendments that not only repeal local ordinances but prohibit government entities from ever passing new ones. Equal Rights Frame Advocates of gay rights ordinances justify such laws by arguing that all citizens, including gays and lesbians, are entitled to equal treatment. [They point to a recent United States Supreme Court opinion which concluded/Douglass Hattaway, who leads an organization that campaigns for gay rights, recently told an audience] that anti-gay rights amendments violate the equal protection clause of the U.S. Constitution by making gays and lesbians ‘unequal to everyone else.’ [The court/Hattaway] went on to argue that ‘in order for there to be equal rights, gays and lesbians must be protected from discrimination.’ Moral Values Frame Critics of gay rights ordinances base their opposition on the argument that such laws undermine moral values. [They point to a recent United States Supreme Court opinion which concluded/Lou Sheldon, who leads an organization which campaigns against gay rights, recently told an audience] that anti-gay rights laws are nothing more than ‘reasonable attempts to preserve traditional American moral values against the efforts of a politically powerful minority group.’ [The court/Sheldon] furthermore criticized gay rights laws as ‘endorsements of immoral behavior.’ Concluding Paragraph Amid the furor, one thing is clear. The debate over gay rights will continue, as both sides battle to win the hearts and minds of legislators and voters. Figure 1. Treatment article. (The italicized headings were not presented to experimental participants. In a further experimental manipulation, each frame was randomly attributed to either a U.S. Supreme Court opinion or an interest group spokesperson.) Framing, Value Words, and Explanations 309 experimental conditions. Each participant was randomly assigned to one of four conditions: (a) exposure to an article that contained no value frame (the control condition), (b) exposure to an article that contained a paragraph-long version of the equality frame, (c) exposure to an article that contained a paragraph-long version of the morality frame, or (d) exposure to an article that contained both frames.2 When both frames were presented, their order of presentation was randomized. The value frames that appeared in the article were verbatim quotes or close paraphrases of real-life exemplars of the frames (compare Figure 1 to the language of the court opinions described above). Rather than attempting to create framing treatments that were perfectly comparable with one another, I produced treatments that reflected actual media content as closely as possible.3 In a further manipulation designed to test whether framing effects differed across source, the frames were randomly attributed to either the United States Supreme Court or to an interest group spokesperson. Given that this manipulation had no effect on the dependent variables analyzed below, I collapsed conditions across source attributions. After reading the articles, participants answered 10 antonym questions taken from an SAT practice test. This task served to clear participants’ short term memory before they proceeded to the posttest. The posttest itself included a battery of closed-ended and open-ended question about gay rights policies. Upon completion of the procedure, participants received a letter explaining the purpose of the experiment. Framing Effects In presenting the results of the experiment, I focus on participants’ posttest responses to two open-ended questions about gay rights. After being asked “Do you favor or oppose laws to protect homosexuals against job discrimination?” participants were instructed to describe “exactly what things went through your mind as you were deciding whether you favored or opposed the policy.” They were given the opportunity to type up to three lines of text in response (taking as much time as they needed). The next question asked respondents whether they favored or opposed “allowing homosexuals to serve in the United States Armed Forces.” This item, in turn, was followed by an open-ended item identical to the one described above. Virtually all of the participants typed in at least some explanation of their views. The responses captured a wide range of reasons for supporting or opposing gay rights. For example, some cited the ability of gays and lesbians to contribute in the workplace or in the military; others cited concerns about the impact of “gays in the military” on the morale or comfort level of heterosexual soldiers; still others cited personal freedom as the standard on which they based their views. Although no one frame dominated, a substantial proportion of the participants (27%) invoked either equality or morality (one participant invoked both). Table 1 reports how often participants invoked equality and morality within each of the four experimental conditions. Altogether, about one in five participants used some form of the word “equal” to explain what they thought about gay rights policies. Eight percent described their views in terms of “moral(s)” or “morality.” Consistent with expectations, the frequency of equality language varied depending on whether participants read the equality frame. Of the participants who read this frame, a fourth invoked equality in their open-ended responses, whereas only 13% of the participants who did not receive the frame mentioned equality. This difference of proportions was significant at p = .01.4 The frequency of morality language varied across framing conditions as well. Of the participants who received the morality frame, 13% mentioned morality when they expressed their opinions about gay rights in their own 310 Paul R. Brewer Table 1 Use of equality and morality language in open-ended responses, by experimental condition No morality frame Morality frame Total No equality frame Equality language: 2 (7%) Morality language: 1 (3%) n = 30 Equality language: 11 (15%) Morality language: 7 (10%) n = 73 Equality language: 13 (13%) Morality language: 8 (8%) n = 103 Equality frame Equality language: 20 (30%) Morality language: 2 (4%) n = 67 Equality language: 10 (19%) Morality language: 8 (15%) n = 54 Equality language: 30 (25%) Morality language: 10 (8%) n = 121 Total Equality language: 22 (23%) Morality language: 3 (3%) n = 97 Equality language: 21 (7%) Morality language: 15 (12%) n = 127 Equality language: 43 (19%) Morality language: 18 (8%) n = 224 words. In contrast, only 3% of the participants who did not receive this frame invoked morality in their answers. Again, the difference of proportions was significant at p = .01. In short, I found that exposure to frames invoking equality and morality led citizens to explain their views in terms of these values.5 One possible interpretation here is that participants’ thought processes regarding the issue were malleable—that participants adopted other people’s value words as their own words. As I show in the following section, however, the framing effects produced by the treatments were more complex than they appeared to be at first glance. The Nature of the Effects To gain a clearer sense of how participants used equality language to explain their views on gay rights, I coded each use of equality language as either endorsing or challenging the pro-gay rights interpretation of equality.6 I followed a similar procedure for each use of morality language, distinguishing between instances where participants used morality language to justify opposition to gay rights and instances where they questioned this interpretation of morality. I found that 30 participants invoked equality language to justify gay rights, as in the following examples: The fact that, in this day and age, people can still believe that others are not worthy of equal rights is incredible and upsetting. It is simply a matter of equal rights for all in the United States, just as it has been with any minority. But 13 participants used equality language to challenge the notion of gay rights as equal rights or the idea that equality should be the principle upon which gay rights policies are judged. For example: Why aren’t there discrimination laws for all kinds of people? Does that not go against equality in the truest sense? Framing, Value Words, and Explanations 311 I think that we should not rely on the government to do everything for us. Life is not easy and it is not up to the government to ensure that we have equality of outcome. Thus, participants used equality language in two distinct ways. Eight participants used morality language to justify opposition to gay rights. For example: Being in the 90s class of “born again Christians” I feel that homosexuality is morally wrong; therefore it should not be sanctioned by our government. It is immoral for homosexuals to be protected in America. . . . Homosexuals representing our country? What does that say about our morals? However, the remaining 10 respondents who invoked morality were more or less critical of the notion that morality and gay rights clashed, as in the following examples: I feel that it is not moral, but I have a hard time not agreeing with such laws because it is not fair to not hire someone based on their homosexuality. Discrimination of any kind is morally repugnant. As with equality language, participants used morality language in two distinct ways. Which ways of using value language did exposure to the treatments encourage? In comparison with participants who were not exposed to the equality frame, participants who received this frame were more likely to invoke equality language in ways that justified gay rights policies (p = .06) but also more likely to invoke equality language in ways that questioned the pro-gay rights interpretation of equality (p = .05). Similarly, participants who were exposed to the morality frame were more likely than others to invoke morality as a basis for opposing gay rights (p = .02) but also more likely to use morality language in ways that questioned this interpretation (p = .07). In short, I found evidence of two different types of framing effects. Exposure to the frames encouraged participants to use value language not only in the ways endorsed by the frames but also in ways that challenged the frames. Thus, participants’ thought processes may not have been as malleable as they initially appeared to be.7 Competing Frames and Framing Effects My final analysis tested whether the frames interfered with one another’s effects. To reiterate, I postulated that exposure to the morality frame might dampen the effect of the equality frame on participants’ use of equality language and that exposure to the equality frame might dampen the effect of the morality frame on their use of morality language. As Table 1 shows, the use of equality language was more common among participants who received the equality frame without the morality frame (30%) than among those who received both frames (19%). On the other hand, the participants who received both the morality frame and the equality frame were slightly more likely to use morality language (15%) than those who received only the morality frame (10%). To test whether these differences across conditions were statistically significant, I estimated models of 312 Paul R. Brewer whether participants used equality language (0 if no, 1 if yes) and of whether participants used morality language (0 if no, 1 if yes). The models included three independent variables: whether participants received the equal rights frame (0 if no, 1 if yes), whether they received the moral values frame (0 if no, 1 if yes), and whether they received both frames (0 if no, 1 if yes). Given that my dependent variables were dichotomous, I used logistic regression to estimate the effects of the independent variables. Table 2 reports the results. The interaction between the equality and morality frames was statistically significant (p = .05) in the model for equality language but did not approach significance in the model for morality language. Whereas the effect of the equality frame was reduced by the presence of the morality frame, the impact of the morality frame did not depend on whether or not participants also received the equality frame.8 Conclusion Before I say more about what the results mean, I should first discuss how broadly applicable they might be. One potential threat to the external validity of my results revolves around the realism of the experiment. Obviously, the simulated media exposure did not perfectly correspond to the conditions of real-life media exposure. However, I took steps to maximize the realism of the experiment: I chose frames that both elites and the media commonly used, and I created the experimental stimuli out of actual newspaper articles. Furthermore, the findings of Nelson, Clawson, and Oxley’s (1997) study suggest that framing effects produced by simulated electronic newspaper articles parallel the framing effects produced by other forms of media. Another threat to the external validity of the findings stems from my relatively narrow and unrepresentative sample. In his classic article on the perils of using “college sophomores in the laboratory,” Sears (1986) warns that reliance on undergraduate student samples may produce biased experimental results. With this in mind, I compared my participants to the respondents from the 1996 American National Election Study (Rosenstone, Kinder, & Miller, 1997), a state-of-the-art representative sample of the U.S. public (see Table 3). On some dimensions (e.g., sex, race), my sample looked like Table 2 Effects of experimental conditions on the use of equality and morality language in open-ended responses Equality language Equal rights frame Moral values frame Equal rights frame × moral values frame Constant Number of observations –2 log-likelihood c2 1.78* .91 –1.54* –2.64 224 221.10 Morality language (.78) (.80) (.91) (.73) 9.08* Note. Table entries are logit coefficients. Standard errors are in parentheses. *p < .05; **p < .01. –.11 1.12 .61 –3.37 224 118.19 7.09** (1.24) (1.09) (1.36) (1.02) Framing, Value Words, and Explanations 313 Table 3 Comparison between experimental participants and 1996 ANES respondents Participants Demographics Median age % African American % female Support for core values (–1 to 1 scale) Mean egalitarianism Mean moral traditionalism Support for an anti-discrimination law (%) Oppose or strongly oppose Neutral Favor or strongly favor Support for “gays in the military” (%) Oppose or strongly oppose Neutral Favor or strongly favor n 20.0 10.3 54.0 .30 –.04 ANES respondents 44.0 12.1 55.2 .12 .25 16.5 19.2 64.3 36.1 N/A 63.9 19.2 33.9 46.9 224 31.2 N/A 68.8 1,714 the ANES sample. On other dimensions, however, my sample was skewed (e.g., age, egalitarianism, moral traditionalism, prior support for gay rights). This may have skewed my findings in some ways. For example, while I found that participants invoked equality more often than they invoked morality, support for equality was unusually high in my sample and support for traditional morality was unusually low. In a representative sample, I might have found more instances of morality language and fewer instances of equality language. But it is not necessarily the case that the framing process would work any differently within a more representative sample: As Sears (1986) himself notes, the majority view in social psychology is that most social psychological processes differ little from a student population to a more general one. Framing scholars have made similar arguments about framing effects (e.g., Nelson, Clawson, & Oxley, 1997; Kühberger, 1998). Yet another possibility is that the nature of my test case limits the external validity of my results. I deliberately chose a domain where value frames loomed large in public discourse. In other issue debates, value frames will not necessarily play as large a role (although they have in a number of cases; see Gamson & Lasch, 1983; Gamson & Modigliani, 1987, 1989; Kellstedt, 2000; Brewer, 2001). It may also be that value frames will produce different effects for “hard” issues than they will for “easy” issues such as gay rights (see Carmines & Stimson, 1980). For example, a value frame for a hard issue may be less likely than a value frame for an easy issue to elicit value language that challenges the frame. Within the bounds of these potential limits, the results have several important theoretical implications. Most obviously, they constitute further evidence that value frames can influence how citizens understand issues. A second implication is that exposure to value frames can encourage more than one way of using value language. Some citizens 314 Paul R. Brewer adopt not only the value words within a frame but also the interpretation of the words that the frame provides; others, however, borrow the value words to express alternative interpretations. A third implication is that framing itself can limit the impact of framing—though it may not do so in every case. By extension, the findings presented here may have implications for the nature of political discussion. Gamson’s (1992) focus group research suggests that citizens use the frames they find in media coverage not only to form their own issue opinions but also to engage in conversations about issues. Gamson (1992) calls such effects “effects in use” (emphasis in the original), arguing that when citizens “use elements from media discourse to make a conversational point of view, we are directly observing a media effect” (p. 180). My results do not directly address the impact of value framing on political conversation; however, they do indicate that value frames can shape the starting points of conversation—namely, citizens’ initial points of view, in their own words. In the case at hand, media framing may lead to conversations about gay rights that revolve around equality and morality. The findings presented here have methodological implications as well. Specifically, they demonstrate that analysis of open-ended responses can advance our understanding of how framing and values interact to produce mass political opinion. Not only can this approach provide an alternative means of testing for framing effects; it can also provide a richer understanding of how people think about frames. Lastly, there are two possible normative frames for my findings. One could point to the results as evidence for the power of framing to mold how citizens understand issues: Give them value words and they will use them. Then again, one could also frame the results as evidence for the limits of that power: A value frame cannot sway all of the people all of the time, particularly when other value frames compete for the audience’s attention. Notes 1. See Nelson, Oxley, and Clawson (1997) and Brewer (2001) for further discussions of the distinction between persuasion and framing effects. 2. It may be that the introductory paragraph suggested a “conflict” frame for the issue. Because all participants read this paragraph, however, its content cannot account for the differences across conditions upon which I base my conclusions. 3. In doing so, I may have crafted stimuli that activated other values as well, such as resentment of a minority group (see Kinder & Sanders, 1996, for a demonstration that a frame can simultaneously activate multiple values). 4. Given that all of my hypotheses specify the directions of expected effects, I present onetailed tests in this study. 5. These findings remained similar when I used logistic regression to control for the effects of the other value frame (i.e., the morality frame for use of equality language and the equality frame for use of morality language), pretest measures of participants’ values, and pretest attitudes toward gay rights, gender, and race. 6. A second coder replicated this procedure. The results indicated that the coding process was highly reliable: The two coders reached the same judgment on all 43 instances of equality language and on 17 of the 18 instances of morality language. 7. One might question whether participants’ invocations of values reflected meaningful thoughts about the issue of gay rights in the first place: Perhaps the open-ended responses were just empty words. To make sure this was not the case, I examined the relationship between the use of value language and another measure of opinion toward gay rights. I used responses to the two closed-ended items described above to create a 9-point index of posttest support for gay Framing, Value Words, and Explanations 315 rights. I then tested whether this index was associated with patterns in participants’ use of value words. The results suggested that participants’ open-ended responses were more than just noise (though they could have been either reasons behind or rationalizations for the closed-ended responses). The participants who invoked equality and used it to justify gay rights were especially likely to score high on the index of support for gay rights (r = .20, p < .01); likewise, the participants who invoked morality as a basis for opposing gay rights were particularly likely to score low on the index (r = –.39; p < .01). Meanwhile, participants who invoked equality and morality in alternative ways were no more or less likely to score high on the index than anyone else. 8. Note that the effect of the morality frame was not significant in the second column of Table 2. What this means is that the impact of the morality frame on the use of morality language was not statistically discernible when the equality frame was absent (the morality frame coefficient in Model 2 captures the baseline effect of this frame when equality frame = 0). As it turns out, an additional analysis showed that the effect of the morality frame was statistically discernible among respondents who received both frames. Still, given that the interaction between the two frames was not significant, I cannot conclude that the impact of the morality frame varied significantly depending on the presence or absence of the other frame. I can only say that, on the whole, the presence of the morality frame influenced whether participants used morality language (based on the difference of proportions test). References Alvarez, R. M., & Brehm, J. (1995). American ambivalence towards abortion policy: Development of a heteroskedastic probit model of competing values. American Journal of Political Science, 39, 1055–1082. Brewer, P. R. (1999). Values, public debate, and policy opinions. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Brewer, P. R. (2001). Value words and lizard brains: Do citizens deliberate about appeals to their core values? Political Psychology, 22, 45–64. Button, J. W., Rienzo, B. A., & Wald, K. D. (1997). Private lives, public conflicts: Battles over gay rights in American communities. Washington, DC: Congressional Quarterly Press. Carmines, E. G., & Stimson, J. A. (1980). The two faces of issue voting. American Political Science Review, 74, 78–91. Dobson, J., & Bauer, G. L. (1990). Children at risk: The battle for the hearts and minds of our kids. Dallas, TX: Word Publishing. Druckman, J. M. (2001). On the limits of framing effects: Who can frame? Journal of Politics, 63, 1041–1066. Evans v. Romer, 882 P. 2d 1335 (Colo. 1994). Feldman, S. (1988). Structure and consistency in public opinion: The role of core beliefs and values. American Journal of Political Science, 32, 416–440. Feldman, S., & Zaller, J. (1992). The political culture of ambivalence: Ideological responses to the welfare state. American Journal of Political Science, 36, 268–307. Gallagher, J., & Bull, C. (1996). Perfect enemies: The religious right, the gay movement, and the politics of the 1990’s. New York: Crown Publishers. Gamson, W. A. (1992). Talking politics. New York: Cambridge University Press. Gamson, W. A., & Lasch, K. E. (1983). The political culture of social welfare policy. In S. E. Spiro & E. Yuchtman-Yaar (Eds.), Evaluating the welfare state: Social and political perspectives (pp. 397–415). New York: Academic Press. Gamson, W. A., & Modigliani, A. (1987). The changing culture of affirmative action. In R. D. Braungart (Ed.), Research in political sociology (Vol. 3, pp. 137–177). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. Gamson, W. A., & Modigliani, A. (1989). Media discourse and public opinion on nuclear power: A constructionist approach. American Journal of Sociology, 95, 1–37. 316 Paul R. Brewer Hochschild, J. (1981). What’s fair? American beliefs about distributive justice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Hurwitz, J., & Peffley, M. (1987). How are foreign policy attitudes structured? A hierarchical model. American Political Science Review, 81, 1099–1120. Kellstedt, P. M. (2000). Media framing and the dynamics of racial policy preferences. American Journal of Political Science, 44, 245–260. Kinder, D. R., & Sanders, L. M. (1996). Divided by color: Racial politics and democratic ideals. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Koch, J. W. (1998). Political rhetoric and political persuasion: The changing structure of citizens’ preferences on health insurance during policy debates. Public Opinion Quarterly, 62, 209– 229. Kühberger, A. (1998). The influence of framing on risky decisions: A meta-analysis. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 75, 23–55. McClosky, H., & Zaller, J. (1984). The American ethos: Public attitudes toward capitalism and democracy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. McGuire, W. (1969). The nature of attitudes and attitude change. In G. Lindzey & E. Aronson (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (2nd ed., pp. 136–314). Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. Nelson, T. E., Clawson, R. A., & Oxley, Z. M. (1997). Media framing of a civil liberties conflict and its effect on tolerance. American Political Science Review, 91, 567–583. Nelson, T. E., & Oxley, Z. M. (1999). Issue framing effects on belief importance and opinion. Journal of Politics, 61, 1040–1067. Nelson, T. E., Oxley, Z. M., & Clawson, R. A. (1997). Toward a psychology of framing effects. Political Behavior, 19, 221–246. Rimmerman, C. A., Wald, K. D., & Wilcox, C. (2000). The politics of gay rights. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Robertson, P. (1993). The turning tide. Dallas, TX: Word Publishing. Rokeach, M. (1973). The nature of human values. New York: Free Press. Romer v. Evans, 517 U.S. 620 (1996). Rosenstone, S. J., Kinder, D. R., & Miller, W. E. (1997). American National Election Study, 1996: Pre- and post-election survey (Study 6896) [computer file]. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, Center for Political Studies, and Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research. Sears, D. O. (1986). College sophomores in the laboratory: Influences of a narrow data base on psychology’s view of human nature. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 515– 530. Sullivan, A. (1995). Virtually normal: An argument about homosexuality. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. Tetlock, P. E. (1986). A value pluralism model of ideological reasoning. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50, 819–827. Vaid, U. (1995). Virtual equality: The mainstreaming of gay and lesbian liberation. New York: Anchor Books, Doubleday. Wald, K. D., Button, J. W., & Rienzo, B. A. (1996). The politics of gay rights in American communities: Explaining antidiscrimination ordinances and policies. American Journal of Political Science, 40, 1152–1178. Zaller, J. (1992). The nature and origins of mass opinion. New York: Cambridge University Press.