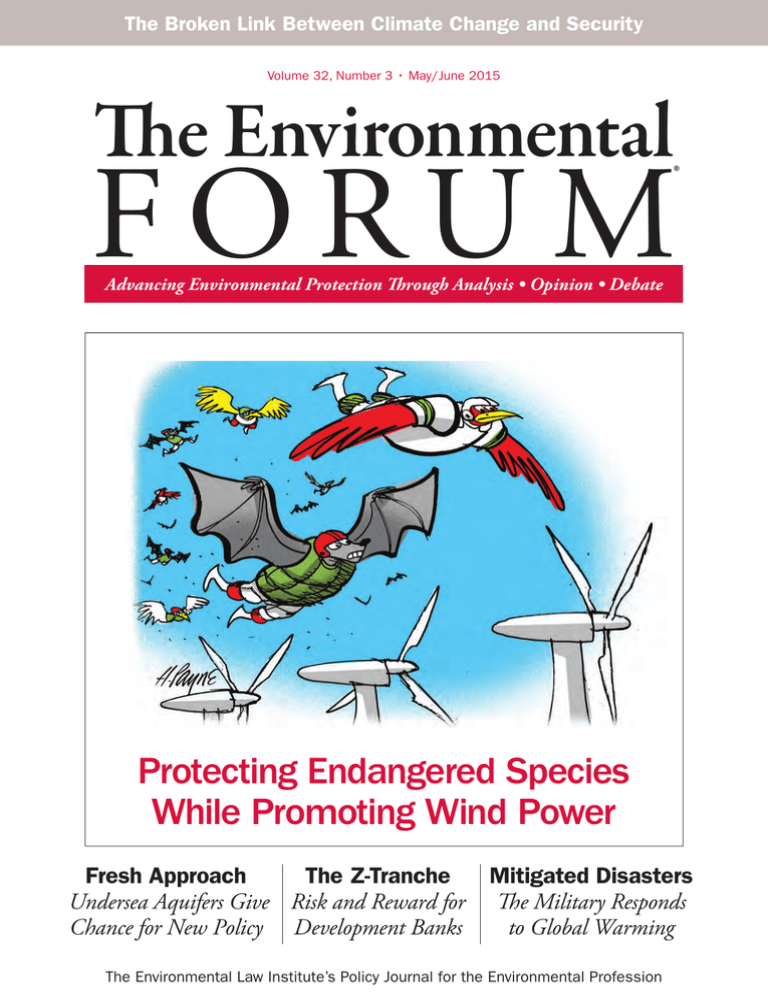

The Broken Link Between Climate Change and Security

Volume 32, Number 3 • May/June 2015

The Environmental

FORU M

®

Advancing Environmental Protection Through Analysis • Opinion • Debate

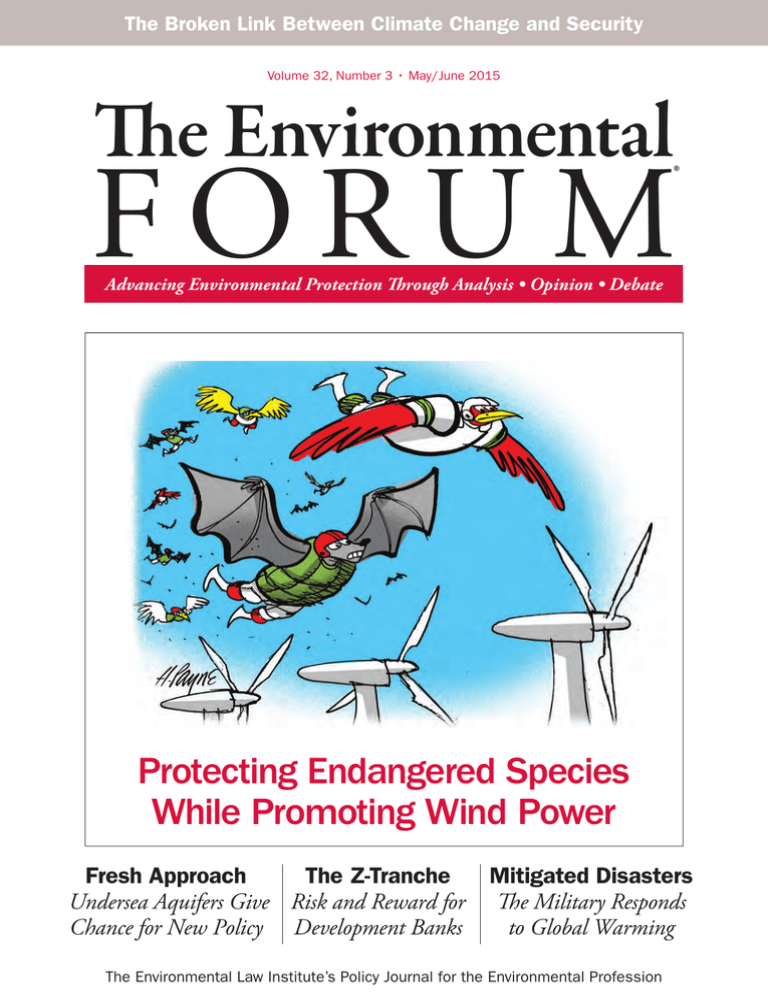

Protecting Endangered Species

While Promoting Wind Power

Fresh Approach

The Z-Tranche

Undersea Aquifers Give Risk and Reward for

Chance for New Policy Development Banks

Mitigated Disasters

The Military Responds

to Global Warming

The Environmental Law Institute’s Policy Journal for the Environmental Profession

Our New Website...

The MIT Press

Why Are We WAiting?

The Logic, Urgency, and Promise

of Tackling Climate Change

Nicholas Stern

engAging the everydAy

Environmental Social Criticism

and the Resonance Dilemma

John M. Meyer

An urgent case for climate change

action that forcefully sets out, in

economic, ethical, and political

terms, the dangers of delay and

the benefits of action.

“This lively, eloquent, accessible

volume models the very style of

social criticism that it calls for in response to this dilemma: a ‘resonant’

environmental criticism that works

on (rather than against) everyday

practices.”

—Lisa Disch, author of Hannah

Arendt and the Limits of Philosophy

The Lionel Robbins Lectures series

376 pp., 21 illus., $27.95cloth

thinking like A MAll

Environmental Philosophy after

the End of Nature

Steven Vogel

“Can there be environmental

philosophy after the end of nature,

a philosophy without romantic

idealization of an authentic natural

order? Steven Vogel’s brilliant new

book offers just such a philosophy.

It is the environmental philosophy

for our time.”

—Andrew Feenberg, author of

Between Reason and Experience and

The Philosophy of Praxis

344 pp., 3 illus., $29 cloth

CiviC eCology

Adaptation and Transformation

from the Ground Up

Marianne Krasny and

Keith Tidball

“Civic Ecology is an inspirational

account of the ecological and

civic renewal of broken places,

such as areas of urban decline. It

describes how local people can,

through stewardship based on

sound social-ecological principles,

re-create sustainable communities

and environments where people

and nature thrive.”

—F. Stuart Chapin III, Professor

Emeritus of Ecology, University of

Alaska Fairbanks

Urban and Industrial Environments series

320 pp., 34 illus., $27 paper

280 pp., $24 paper

FAiled ProMises

Evaluating the Federal

Government’s Response to

Environmental Justice

edited by David M. Konisky

A systematic evaluation of the

implementation of the federal

government’s environmental

justice policies.

American and Comparative Environmental Policy

series • 288 pp., $25 paper

CheMiCAls Without hArM

Policies for a Sustainable World

Ken Geiser

A proposal for a new chemicals

strategy: that we work to develop

safer alternatives to hazardous

chemicals rather than focusing

exclusively on controlling them.

Urban and Industrial Environments series

464 pp., 19 illus., $30 paper

Consensus And

globAl environMentAl

governAnCe

Deliberative Democracy

in Nature’s Regime

Walter F. Baber

and Robert V. Bartlett

“A very valuable resource for policymakers and required reading for

scholars and students interested

in global environmental governance… the book instills hope in

the possibility of integrating placebased research with policymaking

at the global level through deliberative democratic approaches.”

—Maria Grazia Quieti, Dean of

Graduate Studies, The American

University of Rome

278 pp., 1 illus., $25 paper

The MIT Press mitpress.mit.edu

T H E

BR IE F

Offshore Aquifers

FEATURE ❧ The news of possibly vast reserves of groundwater trapped

under continental shelves only heightens the need for improved overall

governance of resource extraction and utilization. Our past exploitation of

global underground water reserves is mute testimony.

By Renee Martin-Nagle

University of Strathclyde

Ralph

Butler

Page 26

The Z-Tranche

FEATURE ❧ Getting people out of cars and trucks and off their mopeds

and into public transportation is not an easy sell. Thus a dynamic

new role for multilateral development banks in the climate change

mitigation saga.

By Michael Curley and Lindsay Haislip

Environmental Law Institute|Cambridge Associates, LLC

Page 32

Birds and Bats and Blades

FEATURE ❧ Long-standing federal laws protecting raptors and other

migratory birds plus rare flying mammals, all of which are challenged

species, are already affecting wind energy development in the United

States. New regulations and industry practices may help.

Henry

Payne

Page 36

By Gordon Smith

Verrill Dana

With a SIDEBAR by Michael Gerrard of Columbia Law School

Testimony: From Vicious to Virtuous

Circles

By Jon Barnett

Melbourne University

SPEECH ❧ We are misunderstanding the challenges that climate change

poses, and we are thereby missing opportunities. Climate change will

not naturally nor inevitably lead to armed conflict, and this is a risk that

is well within our purview to manage.

Page 42

T H E

BR IE F

The Debate: Climate Change Endangers

Security; Can the Military Help Humanity

Respond?

HEADNOTE ❧ As a consequence of the linkages between humanitarian disaster

relief, military organizations, human security, and environmental security, climate

change generates an ever-greater impetus for engagement between military and

civilian authorities. Involvement of both is necessary when disasters overwhelm

the capacity of civil authorities, as is increasingly likely because of the deadly

buildup of atmospheric greenhouse gases.

Page 46

bl o g s

The Federal Beat ...........................

10

By David P. Clarke

Fast Forward ................................... 18

By Ann R. Klee

The Clean Power Plan will produce huge benefits,

but opponents decry the costs.

So many competing ratings that they are

becoming an obstacle to sustainability progress.

Around the States .........................

Science and the Law ....................

12

By Linda K. Breggin

20

By Craig M. Pease

In a turnabout from traditional practice, states

are rejecting their role as laboratories.

Polar ice is disappearing ever faster, causing

sea-level rise and further temperature increases.

In the Courts ..................................

The Developing World...................

14

By Richard Lazarus

By Bruce Rich

No other state court has been as influential as

California’s — a pioneer in many areas of law.

The World Bank pulls back from public

environmental and social evaluations.

An Economic Perspective.............. 16

Notice & Comment .......................

By Robert N. Stavins

Climate negotiations: This is a moment of

considerable opportunity for reform.

22

By Stephen R. Dujack

Twenty-five years in and after 140 columns,

humanity’s survival is ever more at stake.

In the Literature: Oliver Houck on oil and gas development in Louisiana — Page 8

Movers & Shakers: Job changes, awards, and honors — Page 54

ELI Report: ELI moves to a new headquarters at 1730 M St. NW — Page 56

Closing Statement: Scott Schang on the profession’s need for diversity — Page 60

24

The Environmental Law Institute makes

law work for people, places, and the planet. The Institute has played a pivotal role in shaping the fields

of environmental law, policy, and management,

domestically and abroad. Today, ELI is an

internationally recognized independent

research and education center known

for solving problems and designing fair,

creative, and sustainable approaches to

implementation.

ELI strengthens environmental protection by improving law and governance

worldwide. ELI delivers timely, insightful, impartial

analysis to opinion makers, including government

officials, environmental and business leaders, academics, members of the environmental bar, and

journalists. ELI is a clearinghouse and a town hall,

providing common ground for debate on important

environmental issues.

The Institute is governed by a board of directors

who represent a balanced mix of leaders within

the environmental profession. Support for the

Institute comes from individuals, foundations,

government, corporations, law firms, and

other sources.

The Environmental Forum® is the

publication of ELI’s Associates Program,

which draws together professionals in

environmental law, policy, and management. The Forum seeks diverse points of

view and opinion to stimulate a creative

exchange of ideas. It exemplifies ELI’s commitment

to dialogue with all sectors.

For more information about ELI and its Associates Program, contact the Environmental Law Institute, 1730 M Street NW, Suite 700, Washington,

D.C. 20036, 202 939 3800 or 800 433 5120. Or

visit our website at www.eli.org.

The ELI Board of Directors

José R. Allen

Paul Allen

Kathleen L. Barron

Laurie Burt

Alexandra Dunn

Amy Edwards

E. Donald Elliott

Sheila Foster

Pamela M. Giblin

Elizabeth Barrowman Gibson

Phyllis Harris

Alan B. Horowitz

Michael Kavanaugh

Robert Kirsch

Ann R. Klee

Eleni Kouimelis

Stanley Legro

Peter Lehner

Raymond Ludwiszewski

Kathleen A. McGinty

William Meadows

Thomas H. Milch

Tom Mounteer

Granta Y. Nakayama

Vickie Patton

William Rawson

Martha Rees

Nicholas A. Robinson

Edward L. Strohbehn Jr.

(Chairman)

Deborah Tellier

Tom Udall

Daniel Weinstein

Benjamin Wilson

The Environmental Forum Advisory Board

Braden Allenby

Professor of Civil and Environmental

Engineering

Arizona State University

Tempe, Arizona

Lynn L. Bergeson

William Eichbaum

David J. Hayes

Adam M. Finkel

Stephen Shimberg

Vice President

World Wildlife Fund

Washington, D.C.

Managing Director

Bergeson & Campbell, P.C.

Washington, D.C.

Professor

University of Pennsylvania Law

School and Rutgers School of Public

Health

David P. Clarke

Paul E. Hagen

Senior Writer/Editor

Scientific Consulting Group

Gaithersburg, Maryland

4 | T H E E N V I R O N M E N TA L F O R U M

Principal

Beveridge & Diamond P.C.

Washington, D.C.

Distinguished Visiting Lecturer

Stanford Law School

Stanford, California

Principal

SJ Solutions PLLC

Washington, D.C.

Bud Ward

Morris A. Ward, Inc.

White Stone, Virginia

Copyright © 2015, Environmental Law Institute®, Washington, D.C. www.eli.org.

Reprinted by permission from The Environmental Forum®, May/June 2015

The Environmental Forum®

Stephen R. Dujack

Editor

dujack@eli.org

Rose Edmonds

Assistant to the Editor

Brett Kitchen

ELI Report Editor

Marcia McMurrin

Subscription Manager

202 939 3851

mcmurrin@eli.org

Scott Schang

Acting President

Jessica Werber Sarnowski

Director, Professional Education

Kimi Anderson

Sales Associate

202 939 3836

advertising@eli.org

The Environmental Forum® (ISSN 0731-5732)

is the publication of the ELI Associates Program, the

society for professionals in environmental law, policy,

and management. Annual dues are $125 (government,

academic, and non-profit rate: $80). Please call or

email (contact information below) for international

rates. Rates subject to change.

Published bimonthly by the Environmental Law

Institute®. Copyright © 2015. All rights reserved.

Reproduction in whole or in part without written permission is prohibited. Environmental Law Institute,

ELR®—The Environmental Law Reporter®, and The

Environmental Forum® are registered trademarks of

the Environmental Law Institute.

Editorial inquiries should be addressed to the editor by phone: 434 296 3380 or email: dujack@eli.org.

Membership inquiries or address changes should

be addressed to The Environmental Forum, 1730

M Street NW, Suite 700, Washington, D.C. 20036,

phone: 202 939 3851, fax: 202 939 3868, or email:

mcmurrin@eli.org.

ELI publishes Research Reports that present the

analyses and conclusions of the policy studies ELI

undertakes to improve environmental law, policy, and

management.

ELI also publishes magazines and journals — including not only the Forum but also the Environmental

Law Reporter®and the National Wetlands Newsletter

— and ELI Press publishes books, all of which include

a range of opinions by professionals in the field. Our

publications contribute to the education of the profession and the public and disseminate diverse points of

view and opinion to stimulate a robust and creative

exchange of ideas. These publications, which express

opinions of the authors and not necessarily those of the

Institute, its Board of Directors, or funding organizations,

exemplify ELI’s commitment to dialogue with all sectors.

ELI welcomes suggestions for article and book topics

and encourages the submission of editorial queries,

draft manuscripts, and book proposals.

Attention ELI Members,

By reading this magazine,

you are putting your

ELI membership benefits

to work. Be sure to utilize

your other benefits

to the max!

Read @ELI.ORG

Every Monday

All associate

members are

entitled to

receive the

weekly @eli.org

e-mail.This e-mail alerts readers to up-to-the minute job opportunities, seminars, events, publications and other key issues in

environmental law and policy. If you’re not getting this, e-mail

mcmurrin@eli.org today.

Capitalize on Your Networking and Educational

Opportunities

Networking and educational opportunities are at your fingertips

or just a phone call away. Take advantage of the online ELI

Associates Directory and our free seminars and policy forums,

some of which offer you low-cost CLE options.

Listen to past ELI Associate Seminars Online

Need to explain Superfund to an associate? Curious about the

most current issues in air or chemical regulation? ELI Associates

can hear past seminars on a multitude of topics by logging in to

the Just for Members part of the ELI web site. Enjoy 24-hour

access to today’s top experts in environmental law.

Find back issues of The Environmental Forum®

The Environmental Forum® is a unique magazine offering

cutting-edge analysis by expert authors drawn from all sectors of

the environmental debate.The Just for Members part of the ELI

web site provides you exclusive access to Forum indexes going

back to 1982. Some issues are even available online.

Get Great Discounts on Books from ELI Press

You receive a 15% discount on all books published by ELI Press.

See ads in every issue of the Forum for details on recent and

forthcoming books.

Recycled/Recyclable

Soy-based inks

Copyright © 2015, Environmental Law Institute®, Washington, D.C. www.eli.org.

Reprinted by permission from The Environmental Forum®, May/June 2015

M AY / J U N E 2 0 1 5 | 5

f o r u m@ el i.or g

16 U.S.C. §1,

R.I.P.; Reborn

In the twilight of its 2014 session, Congress enacted several substantive changes to conservation law,

particularly through riders in omnibus spending bills. But, a symbolic

shift in conservation law went largely

unnoticed. Congress divorced national park statutes from the rest of

conservation law.

The United States Code collects

and organizes federal legislation

by subject. When Congress enacts

a law, codifiers eliminate repealed

Code sections and insert new provisions where they belong within the

existing organization of prior laws.

The first official codification of

federal law in 1875, Revised Statutes, eventually evolved into the

1925 U.S. Code. In addition to annual updates incorporating new legislation, the Code requires occasional

restructuring to keep its subject matter organization tidy. As Congress

focuses attention on new concerns,

such as the space program, legislation

accumulates and the Code adapts by

adding new titles.

Conservation law grew large

enough by the 1925–1926 publication of the U.S. Code to justify its

own title, the sixteenth in the series,

containing 219 sections over 61

pages. Since that time, it expanded

to around 7,000 sections over nearly

2,500 pages, one of the largest of

all Code titles (but still smaller than

Title 42, “The Public Health and

Welfare,” host of most pollution

control statutes). Now Congress has

spun off laws relating to the national

parks into their own, brand-new

title. Welcome Title 54, “National

Park System”!

The adored national parks play

a prominent role in shaping conservation ethics. Wallace Stegner

famously argued that the national

parks are “the best idea we ever had.

. . . Absolutely American, absolutely

democratic, they reflect us at our best

6 | T H E E N V I R O N M E N TA L F O R U M

rather than our worst.” From a legal

perspective, nothing better encapsulated this American contribution to

“conservation” (the name of Title 16)

than Section 1, establishing “the fundamental purpose” of the park system. The purpose, enacted in 1916,

is “to conserve the scenery and the

natural and historic objects and the

wild life therein and to provide for

the enjoyment of the same in such

manner and by such means as will

leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.”

This first section of the sprawling

title announced the first-order principle of conservation: manage resources

in trust for future generations (unimpaired for their enjoyment). With the

new, separate title for national parks,

this fundamental purpose has lost its

pride of place in conservation law.

I hope agencies implementing the

left-behind conservation legislation

will not lose sight of their connection to the trust ideal. I also hope that

separating national park laws from

other conservation statutes does not

weaken the coordination initiatives

among federal agencies that are universally recommended for adapting

to climate change and maintaining

ecosystem services.

On the bright side, the recodification arrives during the lead-up to

the 2016 centennial for the national

parks. Perhaps it will help focus attention on what is special about national parks, and their urgent need

for better funding and more protection. We can also celebrate that

United States conservation law has

grown to the point that the Code

now spins off the national parks from

other conservation subjects, such as

management of wildlife refuges and

national forests (two entirely separate public land systems), migratory

bird protections, endangered species

recovery, fisheries enhancement, and

wilderness preservation.

Alas, the new Title 54 starts not

with a Section 1, but with section

100101, a number that lacks the

symbolic resonance of the historic

role of the national parks’ mandate.

The senior counsel to the congressional office that maintains the U.S.

Code explained that, “in the case of

Title 54, the layout of the title required 6 digits.” The codifiers have

drained what little romance existed

in Title 16’s numbering scheme.

Although the recodification legislation does not make any substantive changes to the law, it missed an

opportunity to make national park

law easier to find. One reason for

the bulk of national park legislation

is that, unlike the other U.S. public

land systems, Congress established

every one of the 405 units in the

park system. Over time, Congress

increasingly addressed details of individual park unit management, such

as visitor services, hunting, fishing,

grazing, and planning procedures.

These mandates are important but

hard to find in Title 16, where they

are often relegated to footnotes. The

recodification of national park law

failed to incorporate these statutory

provisions into a more user-friendly

framework.

In the meantime, parks await

substantive legal reforms to address

funding, climate-change adaptation,

landscape-scale connectivity, and

threats from upstream and adjacent

land disturbance.

Readers whose hearts are enamored with many of the famous sections of the pollution control laws

should be aware that the House Judiciary Committee is currently considering a bill to recodify those as

well. So, EPA law mavens, prepare

your good-byes to Title 42 and parts

of Title 33. Get ready for Title 55:

“Environment”!

Robert Fischman

Indiana University

Maurer School of Law

forum@eli.org is the place for members

to reply to content in the magazine or

comment on issues confronting the

environmental profession. Our suggested length is 400-800 words.

Copyright © 2015, Environmental Law Institute®, Washington, D.C. www.eli.org.

Reprinted by permission from The Environmental Forum®, May/June 2015

2015 Award Dinner

The Environmental Law Institute

cordially asks you to save the

date for the annual reception

and dinner.

October 20, 2015

Omni Shoreham Hotel

2500 Calvert Street, NW, Washington, DC

ELI thanks our early star

sponsors for their support!

Bergeson &

Campbell, P.C.

National Association

of Clean Water

Agencies

Beveridge &

Diamond PC

Paul Hastings

Gibson, Dunn &

Crutcher LLP

Sidley Austin

Hogan Lovells

Weyerhaeuser

Husch Blackwell LLP

The Wilderness Society

IBM Corporation

For more information about Star Sponsorship,

please contact: Melodie DeMulling, (202) 9393808, demulling@eli.org

Proceeds from the 2015 ELI Award Dinner will

help support the educational and research

mission of the Environmental Law Institute.

In

the

LIterature

is existential, it continues long after

the activities cease, indeed it grows.

Louisiana wetlands are now scarred

by thousands of oil fields, shredded

by over 10,000 miles of pipelines and

By Oliver Houck

access canals, turning rapidly into

open water and sinking into the sea

… which is now rising. South Louin 1901 a wildcatter named W. wood forward were heroic, and their siana is disappearing.

Scott Heywood struck oil near feats in the Louisiana swamps and

The coast here is less a landscape

Beaumont, Texas, and changed marsh wetlands were a kind of hero- than a live body, an interconnectthe Gulf Coast South forever. The ism as well. At the same time, early ed web of root mass (going down

geyser shot 185 feet in the air and on, they also became aware that oil 20 feet and more) and biotic soils,

raged for seven days. It made for and gas development was changing tiny rivulets, plant life and critters

impressive photographs. Ambitions their landscape, which began to fall whose needs are dosed out in natural

flared.

apart. Hence Theriot’s title, includ- rhythms. Oil and gas transects deThat same year a group of Penn- ing energy and coast, embracing stroy the system, turning some areas

sylvania oilmen teamed up with both phenomena. It is as balanced a into stagnant ponds, starving others,

Heywood for a try in Louisiana, history of both of them as one can flushing in salt water, flushing out

targeting the rice plantation of one find until, at the end, he takes sides. the fresh, turning adjacent wetlands

Jules Clement, who knew there was That this reviewer takes another side into ever-expanding arms of an inpetroleum around. He could strike is beside the point. Theriot’s descrip- land sea.

a match and watch the ground go tion of what happened, while not

This simple fact has been the most

up in flames. Nonetheless, fearing complete in all regards, is indeed difficult for the industry, and the

his rice crop might be poisoned and what happened and is well told.

state, to accept. To this day both of

his cattle at risk, he refused the deal

What ensued is not terribly dif- them continue to characterize the

and padlocked his gates.

harm as the surface area

The consortium upped the

of the canals themselves,

American Energy, Imperiled

offer. Money ultimately

which constitute perhaps

Coast: Oil and Gas Development

prevailed, the well went in,

12 percent of the zone, and

in Louisiana’s Wetlands. By

struck oil, and was soon

which misses the point enJason Theriot. Louisiana State

producing several thousand

tirely. The offsite destrucUniversity Press; 271 pages;

barrels a day. In between it

tion is up to 10 times that

$38.00.

ran out of control for eight

figure. Estimate of total

hours and covered Clemcanal impacts range from a

ent’s rice fields with a lake

minimum of 35 percent of

of oil and sand. An apt

coastal land loss to close to

metaphor for what was to

90 percent, the implications

come.

of which would recently beJason Theriot’s book

come, to the oil and gas inAmerican Energy, Imperiled

dustry, terribly threatening.

Coast: Oil and Gas DevelopOne important element

ment in Louisiana’s Wetlands is a story ferent from the course of virtually Theriot contributes to the story is

of what happened next, some eighty all natural resource development in how early the industry knew of its efyears of a wild ride that has not yet America, eastern coal, western min- fects. By the early 1950s its own field

ended, and which breathes the di- erals, timber, cattle, buffalo, fisher- people were reporting it, oystermen

chotomous experience of Clement’s ies — and now the frenetic plays for were suing for damage to their leases,

farm from every pore. Theriot is well natural gas sweeping wherever it is state wildlife officials were complainplaced to write this history. A proud found. We’re never ready for it, the ing about the loss of fur-bearers, and

“product of the oil patch,” his family exploitation goes wild, impacts are then fisheries, and then the marshes

from grandfathers on down, includ- ignored, then denied, then grudg- themselves. Well before the big boom

ing his mother, including Theriot ingly regulated, often weakly and years (1960–1980) to come. Indeed,

himself, all worked in this industry often too late to remedy the harm, although not described in this book

sector, which supported everything and things stumble on. What is dif- a remarkable state biologist named

around them. Oilmen from Hey- ferent in Louisiana is that the harm Percy Viosca was openly warning

TOO BIG TO PAY?

Oil and Gas Development in Coastal Louisiana

I

8 | T H E E N V I R O N M E N TA L F O R U M

Copyright © 2015, Environmental Law Institute®, Washington, D.C. www.eli.org.

Reprinted by permission from The Environmental Forum®, May/June 2015

In

the

LIterature

None of which would read differently from the story of coal in

Kentucky or fracking in the Baaken

Shale, but for a new imperative, the

need to restore this same landscape

before it vanishes. Starting in the

1990s, the state began ambitious

plans for coastal restoration which

today reach astronomic levels of cost,

an estimated $50 billion for simply

holding much of the line as possible

rompted by the Clean Wa- (holding it all is no longer possible),

ter Act and the Coastal Zone and up to $100 billion for creating

Management Act, state officials sustainable deltas for a reasonable pebegan considering regulations for oil riod of time.

and gas development, including sitThe planning has two major chaling restrictions, use of directional lenges, the first of which is that the

drilling, and restoring old canals by measures proposed are not at all

backfilling them, all of which were certain to succeed (in the words of

easily within the ena high corps offigineering capacity

cial recently, it is “a

of the industry, and The industry could have moon shot”). The

modified its activities, second and equally

its financial capacity

as well. The corpopragmatic question

and left a more

rations involved inis, Who pays the bill?

sustainable landscape At which point, sudcluded some of the

wealthiest entities in

denly, the industry’s

the world. The industry could have responsibility for from 35 to 89 peracknowledged the facts, accepted cent of total land loss comes front

regulation, modified its activities, and center. Or, one would think it

and left a more sustainable landscape. would.

As Theriot writes, however, “Not

Oil and gas corporations, howsurprising, the industry went on the ever, have had another answer. They

defensive and successfully fought would form an organization, sevoff much of the criticism for its per- eral in fact, with names like Amerceived environmental footprint.” ica’s Wetland and America’s Energy

One supposes he is correct in not Coast, to sell the message that the

finding this reaction “not surprising.” American public should foot the bill

What industry in America has ever instead. To repair what their industry

been willing to straighten up on its in large part destroyed.

own? In this case, oil and gas went on

In a master stroke, the industry

to coopt state regulators (state legis- recruited several national environlators were already in the bag), defeat mental organizations to join in this

area restrictions, reject alternative effort, their publicity campaigns

access proposals, avoid backfilling, highlighting the values of this coast

deny pollution, and reduce its miti- to America, which a grateful coungation requirements (when required try, so enlightened, willingly pays to

at all) to insignificance. To this day safeguard and restore. One proposal

the state has yet to include offsite diverts existing offshore royalties to

losses when assessing mitigation Louisiana, taking these monies from

needs, and efforts by Army Corps of other states that now receive them.

Engineers officials to do so instead Industry pays nothing more. Other

have been stymied in Congress by, states pay instead. Much mention

of course, the Louisiana delegation. is made in these campaigns of the

Public law failed.

oil and gas infrastructure at risk.

of wetland losses back in 1925 (for

which Governor Huey Long fired

him). Starting in the 1960s scientists

in academia began publishing their

research on this same damage, its

mechanics, its legacy. All of which remained academic, however, until the

advent of environmental law. Then,

it began to matter.

P

Copyright © 2015, Environmental Law Institute®, Washington, D.C. www.eli.org.

Reprinted by permission from The Environmental Forum®, May/June 2015

No word is breathed of oil and gas

involvement in the collapse of the

zone.

At this point, the author and I

part ways. Theriot praises the collaboration here between these environmental groups and the oil majors as

“pragmatic,” a phrase he and quoted

spokesmen liberally use. In context

here, pragmatism means accepting

that the industry is too big to pay its

bills. I have difficulty with this proposition, which would not matter but

for one of the most audacious civil

lawsuits filed in Louisiana juridical

history.

In July 2013 the New Orleans levee board launched a claim against

97 oil and gas companies whose canals and pipelines between the city

and the gulf had destroyed its natural buffer, leaving it open to hurricanes and lesser storms. The damages

sought would be used to restore these

wetlands and bulk up city defenses.

The state, glued to the industry for

generations, reacted violently. The

governor (away campaigning for

president, even then) denounced

“greedy trial lawyers.” His point

man on the coast opined obediently

that the board “got drunk on dollar

signs.” The next session of the legislature saw 17 separate bills to kill the

case. A federal district court, meanwhile, has ruled adversely on the

case (finding inter alia that the harm

complained of was not “proximate”),

an appeal is being filed, and everything is in play.

Theriot’s book ends several years

before this lawsuit, but the conflict he

presents between oil and coast continues unabated. There is something in

the notion of paying for the harm you

cause that will not easily go away. Especially when it is enormous.

Oliver Houck is

professor of law at

Tulane University

in New Orleans,

Louisiana.

M AY / J U N E 2 0 1 5 | 9

T

By David P. Clarke

EPA Faces Clean

Air Act Headwinds

W

ith the rapidly approaching June

deadline for EPA’s final Clean

Air Act regulations governing existing

coal-fired power plants, Republican

opponents are using every opportunity

to assail and, if they can, halt the rules.

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell went so far as to publish an op-ed

in the Lexington Herald-Leader urging

states not to submit compliance plans.

Arguing that Kentucky’s economy would shrink by $2 billion and

“countless” workers would lose their

jobs, McConnell wrote that “refusing to go along” with EPA’s proposal

“would give Congress more time to

fight back,” and lawmakers were “devising strategies now to do just that.”

But amid the attacks by McConnell and other GOP leaders came an

interesting appeal by a Republican

icon, Ronald Reagan’s secretary of state,

George P. Shultz, who in an op-ed of

his own published March 15 in the

Washington Post called for “a Reagan

approach to climate change.” That approach, Shultz argued — after citing

“simple and clear observations” pointing to the global warming threat —

would include significant and steady

funding for energy research and development and a revenue-neutral, escalating carbon tax. It would be an insurance policy.

As EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy told Senate Environment Committee members at a March 4 hearing

10 | T H E E N V I R O N M E N T A L F O R U M

h e

F

e d e r a l

B

e a T

on the agency’s budget proposal, how- testifying, Ohio and Florida, RGGI

ever, every time EPA proposes a rule faults the agency’s proposed rule for in“we hear the same arguments” about sufficiently crediting states’ early actions

the massive costs and minimal or even to achieve power system improvements.

non-existent benefits. McCarthy noted Ohio EPA Director Craig Butler comthat in the last 45 years, the United plained that the federal agency gives no

States has cut air pollution 70 percent credit for the pre-2012 improvements

while GDP has tripled.

and emissions reductions achieved by

In his opening statement, committee its coal-fired power plants.

Chairman James Inhofe of Oklahoma

Citing that and other criticisms —

said the Clean Power Plan will impose including projections that Ohio’s enunacceptable costs on states. Remark- ergy costs will be 39 percent higher in

ing that 32 states oppose the agency’s 2025 under the rules — Butler assured

plan, he claimed it will produce dou- lawmakers that his state would work to

ble-digit electricity price increases. As “prevent this likely illegal rulemaking

for benefits, he said the rules would cut from moving ahead.” Florida’s Public

CO2 concentrations by less than 1 per- Service Commission Chair Art Gracent, reduce global temperature rise by ham also cited various studies that have

less than 0.016 degrees Fahrenheit, and concluded Florida’s electricity prices

reduce sea-level rise by “the thickness of would climb, including one showing

three sheets of paper.”

that the state’s average electric bill may

But EPA’s $1.1 billion budget re- increase between 13 and 17 percent by

quest for climate change and air qual- 2030.

ity improvements is premised on a

EPA’s confidence in the economic

far different perspective, including benefits of its plan, however, also rethe agency’s calculaceived indirect suption that by 2030 the

The Clean Power Plan port from a March

Clean Power Plan will

12 Department of

will produce huge

generate an estimated

Energy report, “Wind

$55 billion to $93 bil- benefits, but opponents Vision: A New Era for

lion per year in health

Wind Power in the

decry the costs

and climate benefits.

United States.” NotThat compares with

ing that wind now

an estimated annual cost of $7.3 billion provides 4.5 percent of U.S. electricity,

to $8.8 billion. Moreover, EPA argues, the 289-page report states that 35 perits flexible approach, based on a view cent wind use by 2050 could lower the

of “the power system as a whole,” will electric sector’s cumulative expenditures

drive innovation and jobs.

by $149 billion and create 600,000

The agency’s perspective received jobs. Importantly, wind deployment

some support at a March 17 House provides “a domestic, sustainable, and

Energy and Power Subcommittee hear- essentially zero-carbon, zero-pollution,

ing on the legal and cost issues of the and zero-water use” electricity resource

proposed rules. The chair of the nine- viable in all 50 states,.

state Regional Greenhouse Gas InitiaBut will U.S. lawmakers ever share

tive’s board of directors, Kelly Speakes- the vision of a clean energy future that

Backman, testified that the region has EPA, DOE, and others are defining

cut carbon emissions more than 40 per- and defending? The answer may be

cent while enjoying 8 percent regional blowing in the headwinds.

economic growth. RGGI’s multi-state,

market-based system that includes elec- David P. Clarke is senior editor/writer with

tricity generation from coal, renewable the Scientific Consulting Group and has more

energy, and other resources would be an than 20 years’ experience in environmental

acceptable compliance strategy under policy as a journalist, in industry, and in

government. He can be reached at davidpaul

the Clean Power Plan.

However, like the other two states clarke@gmail.com.

Copyright © 2015, Environmental Law Institute®, Washington, D.C. www.eli.org.

Reprinted by permission from The Environmental Forum®, May/June 2015

E L I

C L A S S I C S

The Art of Commenting, 2nd Edition

How to Influence Environmental Decisionmaking

With Effective Comments

By Elizabeth D. Mullin

Each business day, the government presents a dizzying array

of formal opportunities for public comment on environmental

decisions. Although many comments are submitted, few are

effective. They miss important issues and bury key points in a

dense body of text written in lawyer-ese.

This second edition of The Art of Commenting takes the

reader through a logical, step-by-step approach to reviewing

environmental documents and preparing comments. You’ll learn

how to prepare for a review, including details on obtaining the

right background materials to develop your perspective and

increase your expertise. This valuable guide also advises on the

present-day reality that most commenting occurs online.

978-1-58576-169-2 • $29.95

You’ll also learn how to organize and write your comments,

including specific examples of what to say, and more

importantly, what not to say. The Art of Commenting is designed

to level the playing field to help you learn the tricks of the trade

that will enable you to participate as effectively as possible in

the environmental decisionmaking process.

Fundamentals of Negotiation

A Guide for Environmental Professionals

By Jeffrey G. Miller and Thomas R. Colosi

Ninety-five percent of federal civil cases settle before trial,

making it essential for lawyers and other professionals

to sharpen their negotiating skills. Negotiating in the

environmental field is especially complex, with diverse

scientific, legal, economic, and political issues. Fundamentals

of Negotiation: A Guide for Environmental Professionals

outlines these techniques and shows you how to manage the

negotiating process to your best advantage.

978-0-91193-728-2 • $29.95

ELI members receive a 15% discount on all ELI

Press and West Academic publications.

To order, call 1(800) 313-WEST,

or visit www.eli.org or westacademic.com

a

By Linda K. Breggin

Stringency Laws

Widely Adopted

T

he intense partisan debate over

federal environmental regulations reached a high water mark with

the Senate majority leader’s recent

call for states to “hold back” on complying with the Clean Air Act rule on

greenhouse gas emissions from existing power plants that will be finalized

this year. With so much attention focused on imposing federal regulatory

standards on states, it seems appropriate to consider the converse — the

extent to which states may adopt regulations more stringent than federal

requirements.

States often have filled gaps left by

federal inaction and, as Justice Brandeis

recognized, can serve as “laboratories of

democracy” where new approaches can

be tried before they are adopted nationally. But the story may not be that

simple — at least when it comes to air

and water quality.

State legislatures across the country have limited the extent to which

regulators can impose environmental standards that are more stringent

than federal requirements. This reduces a state’s options for solving

pressing environmental problems

that federal regulators have not adequately addressed. A 2013 study

by the Environmental Law Institute

finds that 13 states have enacted laws

that contain a blanket prohibition on

adopting standards more stringent

than those in the federal Clean Wa-

12 | T H E E N V I R O N M E N T A L F O R U M

r o u n d

T h e

S

T a T e S

ter Act. In addition, 23 states have tional Conference of State Legislaadopted via legislation, regulation, or tures research, laws that limit the

executive order some type of “quali- ability of state regulatory agencies to

fied” approach that makes it “more adopt air regulations that are more

difficult for states to regulate more stringent than federal standards are

stringently than the federal programs in place in 19 states. Some laws apdo, but stops short of creating a bar ply specifically to air quality and othto state agency action.”

ers more generally to environmental

For example, regulators may be regulations. Similar to ELI’s findings,

required to provide notice and op- NCSL reports that these statutes may

portunity for public comment or impose either unconditional or condiprovide a written explanation that tional restrictions on state regulators.

addresses the environmental benefits

For example, some states simply

and economic implications of a more prohibit more stringent regulations,

stringent state regulation.

such as Kentucky, which requires that

The ELI study also characterized to “preserve existing clean air resources

laws as narrow or broad in scope. while ensuring economic growth”

For example, South Dakota’s law is state regulators may only issue regulabroad, as it applies to measures re- tions “no more stringent than federal

lated, for example, to water pollution requirements.” Similarly, Missouri law

control, livestock discharge control, requires that standards adopted by the

and management of water resources. state air conservation commission may

In contrast, Oregon’s law covers only not be more stringent than those reregulations for nonpoint source pol- quired under the federal Clean Air Act.

lutants from forest operations.

A separate Missouri law prohibits the

In many cases, these laws can state department of natural resources

limit states’ ability to

from adopting any

address a critical isrules more stringent

In a turnabout from

sue — the narrowed

than federal law on

traditional practice,

scope of waters that

emissions from power

are covered by the states are rejecting their plants fired by MisClean Water Act.

souri coal.

role as laboratories

The act applies to

The reasons for

“navigable waters”

enacting these laws

— a definition that has been the sub- undoubtedly vary from state to state,

ject of highly controversial Supreme but Professor Jerome Organ theorizes

Court decisions that have limited the that both economic and institutional

reach of the law, most notably with concerns drive stringency legislation.

respect to wetlands and streams.

Economic factors could include inIn the wake of these decisions, ELI dustry compliance costs, whereas

explains that in some cases waters institutional concerns could include

that previously were protected are no distrust of state agencies.

longer covered and in other cases it is

Although state laws vary considerunclear whether the Clean Water Act ably in purpose, scope and approach,

applies. According to Senior Attorney it is clear that many states are limited

Bruce Myers, “States that have strin- in their ability to raise the environgency laws on the books can still leg- mental protection bar and fill gaps

islate to protect vulnerable waters in that have resulted in part from the

the wake of the Supreme Court rul- partisan divide over federal environings, but state environmental agencies mental regulation.

in these jurisdictions may be hindered

or even prohibited from doing so, de- Linda K. Breggin is a senior attorney in

pending on the nature and reach of ELI’s Center for State and Local Environthe particular provision.”

mental Programs. She can be reached at

Similarly, according to 2014 Na- breggin@eli.org.

Copyright © 2015, Environmental Law Institute®, Washington, D.C. www.eli.org.

Reprinted by permission from The Environmental Forum®, May/June 2015

Livelihoods,

Natural Resources,

and Post-Conflict

Peacebuilding

Edited by Helen Young

and Lisa Goldman

Series: Post-Conflict Peacebuilding and Natural Resource Management

Routledge • April 2015 • Paperback: 978-1-84971-233-0: $84.95

Sustaining and strengthening local livelihoods is one of the

most fundamental challenges faced by post-conflict countries.

By degrading the natural resources that are essential to livelihoods

and by significantly hindering access to those resources, conflict

can wreak havoc on the ability of war-torn populations to survive

and recover. This book explores how natural resource management

initiatives in more than twenty countries and territories have

supported livelihoods and facilitated post-conflict peacebuilding.

Case studies and analyses identify lessons and opportunities for the

more effective design of interventions to support the livelihoods

that depend on natural resources – from land to agriculture,

forestry, fisheries, and protected areas. The book also explores larger

questions about how to structure livelihoods assistance as part of a

coherent, integrated approach to post-conflict redevelopment.

Livelihoods, Natural Resources, and Post-Conflict Peacebuilding is part

of a global initiative to identify and analyze lessons in post-conflict

peacebuilding and natural resource management. The project has

generated six books of case studies and analyses, with contributions

from practitioners, policy makers, and researchers. Other books in

this series address high value resources, land, water, assessing and

restoring natural resources, and governance.

To find out more visit www.routledge.com/9781849712330 today!

Author Biography

Helen Young is a professor at the Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy at Tufts University

and a research director at the school’s Feinstein International Center.

Lisa Goldman is a senior attorney at the Environmental Law Institute.

www.routledge.com

I

By Richard Lazarus

California Dreamin’:

Court Is the Leader

W

hile the environmental law

docket of the U.S. Supreme

Court has been relatively quiet this year,

the same cannot be said of the California Supreme Court. As chronicled best

by U.C. Davis law school Professor

Rick Frank, whose expertise in California environmental law is legendary, the state’s high court currently has

21 environmental cases on its docket.

The sheer number and breadth of the

issues covered by those cases says a lot

about environmental law’s evolution

and serves as a ready reminder of California’s long-standing preeminence at

environmental law’s cutting edge.

Frank’s list includes 10 cases arising

under the California Environmental

Quality Act. The most recent addition

is Cleveland National Forest v. San Diego Assn of Governments, concerning the

relationship of CEQA to California’s

Sustainable Communities and Climate

Protection Act of 2008. CEQA is California’s version of the federal National

Environmental Policy Act, but, unlike

NEPA, has substantive teeth.

NEPA requires federal agency consideration of the environmental impacts of any major federal action significantly affecting the quality of the

human environment. However, NEPA,

as the U.S. Supreme Court has stressed,

is “essentially procedural” and does not

itself require an agency to avoid those

impacts. The same is not true under

California’s CEQA, and a state agency

14 | T H E E N V I R O N M E N T A L F O R U M

n

T h e

C

o u r T S

can approve a project lacking the nec- and Interior, the California Supreme

essary environmental mitigation only Court’s docket makes clear that it is

upon also detailing in writing the sub- state and not federal environmental law

stantive justifications for doing so.

where the rubber meets the road.

Much federal NEPA regulation,

To be sure, in many instances, fedmoreover, can be traced to CEQA, es- eral environmental law triggered the

pecially from those years in the Carter emergence of that state law in the first

administration when the President’s instance. But with the demise of sigCouncil on Environmental Quality nificant congressional environmental

was dominated by Californians, such lawmaking for more than two decades,

as Nicholas Yost, who championed the state environmental law is frequently

drafting of the first NEPA regulations. where the most exciting lawmaking inIf past is at all prologue, the California novations are occurring and where liticourt’s CEQA rulings may find later ex- gation naturally follows.

pression in federal NEPA law.

Second, California is not just any

The 10 CEQA cases just top the list. state for environmental law. No other

The California court’s environmental state has served as such an important

docket includes, among others, a pri- incubator of environmental lawmaking

vate property rights challenge to water for the entire nation. Much of federal

conservation diversion plans (Property environmental law, including the Clean

Reserve v. Superior Court), an industry Air Act and the Resource Conservalawsuit against inclusionary zoning tion and Recovery Act, finds its origins

(California Building Assn v. City of San in California, as do the laws of many

Jose), and a claim that federal mining other states. Both President Obama’s

law preempts a state criminal prosecu- hugely important greenhouse gas emistion for violating state mining law (Peo- sions standards for new motor vehicles

ple v. Rinehart).

and his Clean Power Plan for regulation

Nor is the stunning number of of existing power plants find inspiracases on the docket a

tion and substance in

mere expression of the

California’s innovative

No other state court

number of environGlobal Warming Sohas been as influential

mental law cases being

lutions Act of 2006.

litigated in that state’s

Finally, the Cali— a true pioneer in

lower courts. The California

Supreme Court

many areas of law

fornia Supreme Court,

is not just any state

like the U.S. Supreme

supreme court. No

Court, enjoys discretionary jurisdic- other state court has been as influential

tion. The state justices therefore get to — a true pioneer in many areas of law.

pick and choose which of many cases It is not surprising that according to a

are sufficiently important to warrant recent survey by LexisNexis, no other

their plenary review. And, never before state court has had its rulings followed

has that court applied that standard and as frequently.

decided to hear so many environmental

Governor Jerry Brown seems both

cases.

well aware and very much wanting to

The California court’s environmen- embrace that tradition of judicial actal docket’s significance is three-fold. tivism. He has appointed three of the

First, it confirms the extent to which Court’s seven justices, none of which

the action in environmental law is in- had any prior judicial experience and

creasingly occurring at the state rather two of whom were law professors. Not

than federal level. To most practitioners a typical recipe for judicial restraint.

of environmental law, this is hardly

headline news. But to law students, law Richard Lazarus is the Howard J. and Kathprofessors, and those used to thinking erine W. Aibel Professor of Law at Harvard

about environmental law exclusively University and can be reached at lazarus@

through the lens of Congress, EPA, law.harvard.edu.

Copyright © 2015, Environmental Law Institute®, Washington, D.C. www.eli.org.

Reprinted by permission from The Environmental Forum®, May/June 2015

Environmental Justice 3RD Edition

By Barry E. Hill

nvironmental justice activists and advocates argue that

your race and socioeconomic status should not dictate

the environmental health risks you face. The environmental

justice movement is aimed at avoiding, minimizing, or

mitigating disproportionately high and adverse human

health and environmental impacts, including social and

economic impacts, on minority and/or low-income

communities, and at ensuring disadvantaged communities

are engaged meaningfully in the environmental

decisionmaking processes.

The 3rd edition of Environmental Justice: Legal Theory and

Practice provides an overview of this environmental and

public health problem and explores the growth of the

environmental justice movement. It analyzes the complex

mixture of environmental law and civil rights legal theories

adopted in environmental justice litigation.

About the Author

arry E. Hill is an Adjunct Professor of Law at Vermont

Law School, where he has taught an environmental

justice and sustainable development course for 20 years.

Mr. Hill is Senior Counsel for Environmental Governance,

Office of International and Tribal Affairs, U.S. Environmental

Protection Agency (EPA). Previously, Mr. Hill was Director of

EPA’s Office of Environmental Justice from 1998-2007. He

served as a Visiting Scholar at the Environmental Law

Institute from 2010 - 2012. Mr. Hill received his B.A. degree

in Political Science from Brooklyn College; M.A. degree in

Political Science from Howard University; and a J.D. degree

from the Cornell University Law School. He has published

numerous articles on environmental law and policy, and

environmental justice.

ISBN: 978-1-58576-159-3

$89.95 | Paperback

ELI members receive a 15% discount on all

ELI Press and West Academic publications.

To order, call 1(800) 313-WEST,

or visit www.eli.org or westacademic.com

“As a New York City Housing Court judge, I saw daily in my courtroom the negative effects

on minority and/or low-income communities of the relationship of zoning and land use

decisions to environmental injustices. Professor Hill’s examination of the citizen’s quest for

recognition of a human right to a clean and healthy environment in the United States is a

tour de force...an indispensable book for students, practitioners, and judges who can

benefit from this clear, comprehensively-researched, and well-written guide to an

exceedingly complex subject.”

—Pierre B. Turner, Judge, New York City Housing Court (ret.)

a

By Robert N. Stavins

The IPCC at

a Crossroads

T

he Intergovernmental Panel on

Climate Change plays an important role in global warming policy around the world. This is largely

because its reports enjoy a degree

of credibility that renders them influential for public opinion, and —

more importantly — because the

reports are accepted as a definitive

source by international negotiators

working under the United Nations

Framework Convention on Climate

Change.

But the IPCC is now at a crossroads. Its Fifth Assessment Report

is complete and largely successful.

But, like many large institutions, the

IPCC has experienced severe growing pains. Its size has increased to

the point that it has become cumbersome, it sometimes fails to address the most important issues, and

— most striking of all — it is now

at risk of losing the participation of

the world’s best scientists, due to the

massive burdens that participation

entails.

The good news is that this is a moment of considerable opportunity for

addressing these and other challenges, because the direction of future

assessments is now open for discussion and debate. In February, the 195

member countries of the panel met

in plenary session in Nairobi, Kenya,

to discuss — among other topics —

the future of the IPCC.

16 | T H E E N V I R O N M E N T A L F O R U M

n

e

C o n o m I C

P

e r S P e C T I v e

Just one week before the Nairobi raro served as vice-chair, and Kolssessions commenced, another, much tad and I served as coordinating lead

smaller meeting took place about authors, all of Working Group III of

4,000 miles to the northwest — in the IPCC’s Fifth Assessment Report,

Berlin. Twenty-four participants but our organizing of the workshop

with experience with the IPCC met and our authoring of this memoranfor a three-day workshop on the fu- dum were carried out in our roles as

ture of international climate-assess- researchers, and completely indepenment processes. The aim was to take dently of our former official capacistock and reflect on lessons learned ties within the IPCC.

in past assessments in order to idenAmong our recommendations

tify options for improving future as- were these: The IPCC should signifisessment processes.

cantly reduce the number and length

Participants included social scien- of meetings, and rely more on webtists who contributed in various ca- based communication among lead

pacities to the Fifth Assessment Re- authors; it should seek to improve

port and earlier IPCC assessments, the scoping process to better identiusers of IPCC reports (from national fy relevant policy questions; reports

governments to intergovernmental should be made more concise and

organizations), and representatives more accessible to policymakers; inof other stakeholder groups. Par- put from social scientists should be

ticipants came from both developed increased; opportunities for climate

and developing countries, and dis- scientists from developing countries

cussions were held under Chatham should be improved, independent of

House rules, with no public attribu- their current country of residence;

tion of any comments to individuals. and the IPCC would benefit from

The workshop (“Assessment and greater interactions with other reCommunication of the

search institutions.

Social Science of CliU n f o r t u n a t e l y,

This is a moment

mate Change: Bridgwhen the IPCC memof considerable

ing Research and Polber countries met in

icy”) was co-organized

February to discuss

opportunity

by four academic and

the future of the infor reform

research organizations:

stitution, few of these

Italy’s Fondazione Eni

concerns were adEnrico Mattei, Germany’s Mercator dressed concretely, if at all. As is ofResearch Institute on Global Com- ten the case with institutions, change

mons and Climate Change, and the is difficult.

United States’ Stanford EnvironmenOver the coming months, we

tal and Energy Policy Analysis Cen- will produce a comprehensive report

ter and Harvard Project on Climate from our Berlin workshop in time for

Agreements.

the IPCC’s next meeting, in October,

Now is a moment of opportunity, as well as the subsequent UNFCCC

because the future of the IPCC is meeting in Paris in December, where

open for discussion. In this context, a binding agreement is expected.

two of my co-organizers — Carlo When that report is available, I will

Carraro of FEEM and Charles Kols- bring it to the attention of readers of

tad of Stanford — and I wrote a brief this column.

memorandum, based on our reflections on the Berlin workshop discus- Robert N. Stavins is the Albert Pratt Profession. We described a set of specific sor of Business and Government at the John

challenges and opportunities facing F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard

the IPCC, and provided options for University, and Director of the Harvard Enimproving the process of assessing vironmental Economics Program. He can be

scientific research. Note that Car- reached at robert_stavins@harvard.edu.

Copyright © 2015, Environmental Law Institute®, Washington, D.C. www.eli.org.

Reprinted by permission from The Environmental Forum®, May/June 2015

Next Generation Environmental Compliance

and Enforcement

LeRoy C. Paddock and Jessica A. Wentz, editors

Next Generation Environmental Compliance and Enforcement is a

compilation of selected papers from a workshop held in December

2012 that convened EPA representatives and other stakeholders to

exchange ideas and develop strategies for implementing a “Next

Generation” approach to environmental enforcement and

compliance. These papers cover a broad array of topics, ranging

from relatively abstract comparisons of different compliance

approaches to focused case studies of regulatory programs.

Some of the specific mechanisms identified by the authors to

streamline enforcement and compliance include: advanced

monitoring technologies, self-certification programs, company

compliance management systems, environmental petitions,

insurance mechanisms, and regulatory approaches that leverage a

company’s internal economic interests to drive behavior.

“This book offers valuable insights needed to find smarter ways to

enforce environmental regulation. The kind of innovative thinking

represented here could not come at a better time, as government increasingly faces the need to address

environmental challenges under conditions of fiscal austerity.” —Cary Coglianese, Edward B. Shils Professor of

Law, University of Pennsylvania

“To its credit, EPA has acknowledged shortcomings in its efforts to promote compliance with the environmental

laws. EPA’s important 2012 conference … represents a creative initiative to grapple with these challenges. Next

Generation … will be of value to scholars, policy makers, and others interested in understanding the challenges

associated with promoting compliance, and traditional, and emerging, opportunities to address these challenges.”

—Dave Markell, Associate Dean for Environmental Programs and Steven M. Goldstein Professor, Florida State

University College of Law

ISBN: 978-1-58576-163-0 | Price $69.95 • 340 pp.

ELI members receive a 15% discount on all ELI

Press and West Academic publications.

To order, call 1(800) 313-WEST,

or visit www.eli.org or westacademic.com

F

By Ann R. Klee

Ratings Good for

the Environment?

E

very day, we make decisions based

on ratings, from the cars we drive

and appliances we buy, to the restaurants we eat at and movies we see. Increasingly over the past few years, the

theory has been that investors too could

be persuaded by so-called green ratings

for corporate sustainability. That has

led to a proliferation of green ratings

groups: CDP, DJSI, Bloomberg Sustainability Reporting Initiative, Newsweek’s Green Rankings, CK Capital,

Inrate, Oekom, etc.

The initial intent was a good one:

to encourage transparency and comparable metrics so that the relative “environmental, social, and governance”

performance of publicly traded companies could be meaningfully assessed.

Certainly, there is much to be said for

an independent review of a company’s

ESG metrics, and most companies

have voluntarily participated in the

green ratings process. An independent

review of ESG performance, if done

properly, can provide stakeholders with

meaningful information while also allowing companies to optimize internal

resources.

Unfortunately, there are now so

many competing ratings and rankings

that they are becoming an obstacle to

sustainability progress. Further, recent

research conducted by The Conference

Board suggests that institutional investors adjust decisions based on when

companies’ efforts gain media attention

18 | T H E E N V I R O N M E N T A L F O R U M

a S T

F

o r w a r d

rather than on how they reflect actual detail on its methodology and also help

measures of performance.

us to “improve” our score. The amount

There are three fundamental prob- of the fee depended upon how much

lems with the current state of green rat- detail we wanted. This kind of “pay

ings. First, companies today can spend to play” approach does nothing to adthousands of hours responding to the vance sustainable development and evsurveys that generate the ratings. Each erything to undermine the credibility

survey is different, and even questions of green ratings.

addressing similar topics — such as

Many companies are already takgreenhouse gas emissions — are often ing steps to address these issues. They

framed differently, requiring tailored are being much more selective on the

responses and adding to the burden. rating/ranking groups that they enIn 2014, for example, GE developed gage, focusing on those that are themresponses to more than 650 individual selves transparent and relevant to their

questions from ratings groups. The pro- industries or customers. Over time,

cess took several months and involved this will result in a shake out of rating

more than 75 people across the orga- organizations that charge for related

nization, with virtually no value to our consulting services or demand reams

customers or shareholders and even less of data that are not relevant to a comimpact on the environment. Having pany’s strategy.

too many competing rating groups diCompanies are also using their own

verts resources from activities that can performance measures and metrics, not

truly impact sustainability.

trying to redefine them just for external

Second, the granularity of data re- ratings. And they are focusing on those

quested by some surveys is also of ques- issues that are material to their operationable value. Some surveys, for ex- tions. For energy-intensive industries,

ample, ask for data on

that may be focusing

water usage by prodon greenhouse gas

So many competing

uct SKU or water disemissions and efficienratings that they are

charge by basin. These

cy. For forest products

data are difficult, if not becoming an obstacle to companies, it may be

impossible, to calcu- sustainability progress biodiversity. Materiallate and leave much

ity is a critical element;

to the interpretation

on this point, the

of the responder. Should water usage Sustainability Accounting Standards

include the supply chain? Who defines Board is working to develop metrics

the water basin? And why demand a and a reporting framework by indusper-product SKU measurement when try sector.

it is the total water use that is both more

Over time, I’m hoping a transparrelevant and more accurately measured? ent approach that facilitates public disThis is just one example of the detailed semination of comparable information

nature and questionable relevance of focused on metrics that matter to the

information requested in some surveys. ESG performance of the industry secFinally, and most perniciously, is tor as a whole will evolve. If we’re sethe inherent conflict of interest that rious about meaningful reporting on

underlies the business strategy of some ESG performance, the focus should

of even the more highly considered be on targeted, business-relevant metrating groups. Some organizations, for rics and a simple, transparent reporting

example, serve as both a rating entity process. The era of being part of a green

and then a provider of consulting ser- ranking just for the sake of being rated

vices. Several years ago, GE was rated has passed.

by one of these groups. When we asked

for further explanation on our “score,” Ann R. Klee is vice president, global operawe were told that for a consulting fee, tions — environment, health & safety, of GE.

the rating organization would provide She can be contacted at Ann.Klee@ge.com.

Copyright © 2015, Environmental Law Institute®, Washington, D.C. www.eli.org.

Reprinted by permission from The Environmental Forum®, May/June 2015

Protecting the Environment Through Land Use

Law: Standing Ground

By John R. Nolon

John R. Nolon’s Protecting the Environment Through Land Use

Law: Standing Ground takes a close look at the historical struggle of local governments to balance land development with

natural resource conservation. This book updates and expands

on his four previous books, which established a comprehensive

framework for understanding the many ways that local land

use authority can be used to preserve natural resources and

environmental functions at the community level. Standing

Ground describes in detail how localities are responding to new

challenges, including the imperative that they adapt to and

help mitigate climate change and create sustainable neighborhoods. This body of work emphasizes the critical importance of

law in protecting the environment and promoting sustainable

development.

Nolon looks at the legal foundations of local environmental law

within the federal legal system, how traditional land use techniques can be used to protect the environment, and innovative

and flexible methods for protecting fragile environmental areas

and for making urban neighborhoods livable.

Standing Ground is both a call to action—challenging readers to consider how local law and policy can augment state and federal conservation efforts—and a celebration of the valuable role local governments play in

protecting our environment.

“When it comes to the subject of local environmental law, John Nolon is a passionate, inspirational, and

authoritative guide and teacher. The rest of us—lawyers, planners, professors, judges, public officials, and citizen

activists—have all benefited from his insights and have been challenged to think carefully and creatively about the

ways in which local law and policy can augment and improve upon federal and state efforts to protect our fragile

environment from a growing number of threats.”

—Michael Allan Wolf, Richard E. Nelson Chair in Local Government Law,

University of Florida Levin College of Law

To order, call 1(800) 313-WEST, or visit www.eli.org or westacademic.com

Price $69.95 • 628 pp.

ELI members receive a 15% discount on all ELI Press and West Academic publications.

S

By Craig M. Pease

Melting Ice and

Human Civilization

I

ce melts when it warms. And climate change driven by ever-increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide

levels is now melting hundreds of cubic miles (yes, cubic miles) of polar

ice each year. This amount of melting ice is almost inconceivable. Ponder for a moment a gargantuan ice

cube, a mile on each side, and then

think about hundreds of those melting each year. And if that is not bad

enough, this melting is accelerating.

The melting ice is found in the

Arctic Ocean, Greenland, and Antarctica, on both land and sea. The

Polar Science Center finds the loss of

70 cubic miles of Arctic sea ice each

year, going back to the late 1970s. In

their Science paper from earlier this

year, Fernando Paolo and colleagues

find that the modest five cubic miles

of Antarctica sea ice lost per year in

the 1990s and early 2000s has now

accelerated, to the loss of 70 cubic

miles per year. On land, V. Helm and

colleagues’ Cryology paper from last

summer documents the loss of some

90 cubic miles of ice each year from

Greenland, and the loss of 30 cubic

miles from Antarctica land each year.

Why should we be concerned

about the melting of polar ice? After

all, most all of human civilization is

found in the temperate zones and

the tropics. Most obviously and simply, the polar melting is a harbinger

of a warmer climate everywhere on

20 | T H E E N V I R O N M E N T A L F O R U M

C I e n C e

a n d

T h e

l

a w

Earth. Models consistently predict when that ice melts, it is replaced

more and faster initial warming in by open water, which absorbs the

the Arctic, exactly as we are seeing, sunlight that used to be reflected.

as evidenced both by direct measure- As Arctic sea ice melts, it accelerates

ments of temperature, and all that Arctic warming.

melting ice.

What happens in the Arctic does

More directly and specifically, as not stay in the Arctic. The melting

this polar ice melts, there are rever- polar ice is now altering winds and

berations, quite literally, across the currents.

entire surface of the Earth, impactStefan Rahmstorf and colleagues’

ing human societies everywhere, by Nature Climate Change paper from

causing rising sea levels, less reflec- earlier this year shows how melting

tion of sunlight back into space, and of Greenland’s ice has now slowed

shifts in the ocean currents and high the ocean currents that move warm