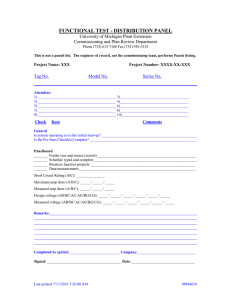

Screening Criteria for Operating in Parallel with

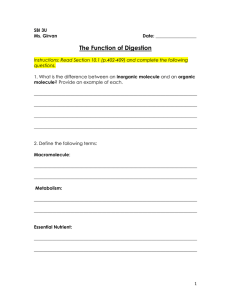

advertisement