The status of the least documented language families in the world

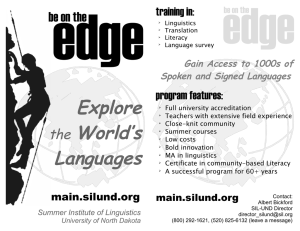

advertisement