International Program

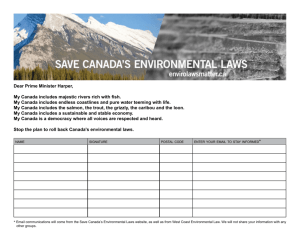

advertisement