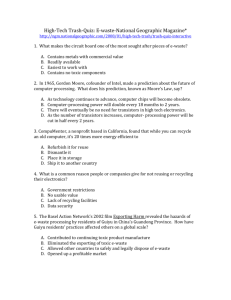

Current Situation and Economic Feasibility of e

advertisement