Nova Law Review 30, 2 - NSUWorks

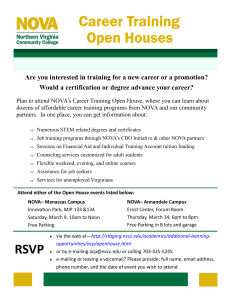

advertisement