Strengthening Collaboration in Ontario`s Not‐for‐profit Sector

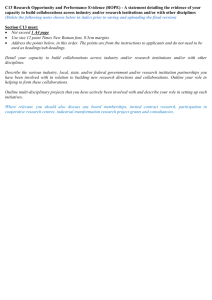

advertisement