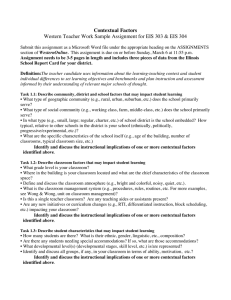

here - HKUST Business School

advertisement