A world without inflation

advertisement

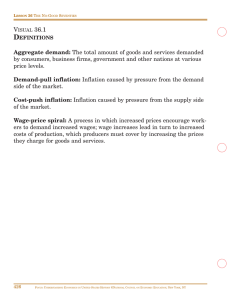

N°30 MARCH 2016 ECONOTE Societe Generale Economic and sectoral studies department A WORLD WITHOUT INFLATION The huge money creation of Quantitative Easing (QE) has led to concern about runaway inflation in developed countries. So far, however, those fears have not materialized. Quite the opposite, as in most of these countries the inflation rate remains below or well below the official targets of the main central banks (typically 2% or just below). Global inflation has been on a downward trend since the early 1980s. This paper argues that the advent of anti-inflation-oriented central banks in the late 1970s combined with structural shifts in the global economy, such as globalization, technological innovations and weakening trade union influence, have been key factors behind falling trend inflation in the developed world. Since 2008, this strong disinflationary trend has been compounded by a powerful negative demand shock. Will inflation remain low? We expect core inflation (excluding volatile food and energy prices) to remain low across much of the developed world in the foreseeable future. This is partly because of structural trends, which have likely durably reduced the long-term inflation rate. But this is also due to enduring weak aggregate demand and wages. Moreover, there is a real danger that current low inflation will actually become self-perpetuating. This is because, in a world of very low inflation, the probability increases that three crucial constraints will bind: 1) the difficulty for central banks to reduce their policy rates substantially below zero, 2) sticky nominal wages, and 3) Fisherian debt deflation mechanisms. As these constraints become binding, economies are left grappling with higher unemployment and underutilization of production capacity which, in turn, keep exerting downward pressures on prices. Marie-Hélène DUPRAT +33 1 42 14 16 04 Mariehelene.duprat@socgen.com ECONOTE | No. 30 – MARCH 2016 Over the past few years, some observers have expressed concern about high future inflation in advanced economies because of the huge rise in central bank balance sheets and the sharp increase in fiscal deficits1. These predictions of high inflation rest on the monetarist argument that nominal income is proportional to the money supply. The monetary approach assumes a stable demand for real money balances. It is argued that, given aggregate supply constraints in the short run, an expansion of the money supply is bound to lead to higher prices. So, the argument goes, the unprecedented money printing by central banks in the developed world since 2008 is a sure harbinger of high inflation. So far, however, those fears have not materialized. Quite the opposite, in fact, as in most developed countries, the inflation rate remains below or well below the official targets of the main central banks (typically 2% or just below). So should we be worried about high future inflation? We would argue that the answer to that question is negative for four main reasons. The first reason relates to structural changes, especially globalization and the spread of technological innovations, which are expected to keep exerting constant downward pressure on inflation from the supply side. The second reason is that, since 2008, most advanced economies have fallen into a liquidity trap (when the zero lower bound on the central bank policy rate is strictly binding), and suffer, as a consequence, from chronically deficient aggregate demand. When an economy is in a liquidity trap, the link between the money supply and nominal GDP breaks down (or to put it otherwise, the quantity theory of money does not hold any more) owing to the dramatic increase in the private sector’s willingness to hoard money instead of spend it. The third reason concerns the lack of evidence of a wage-price spiral. We believe that structural trends (such as declining union influence and rising labour-market flexibility), coupled with continued slack in the labour market in much of the developed world, will underpin generally sober growth in wages (the main driver of sustained inflation) in the foreseeable future. And finally, with inflation dropping to very low levels, there is a serious risk that a vicious circle of selfperpetuating economic weakness could be set in motion that might leave much of the developed world stuck into a low-inflation trap. Part of the reason is the fact that low inflation increases real debt burdens and thus weakens aggregate demand still further. Another reason is that sticky nominal wages can prevent real wages from adjusting downward to clear the labour market2. A MULTI-DECADE DOWNWARD TREND IN INFLATION A GLOBAL PHENOMENON Prior to the mid-1960s, low inflation was the norm across the developed world rather than the exception. Inflation began ratcheting upward in the mid-1960s, and, by the late 1970s, had reached levels unheard of in peacetime, a reflection in part of the 1973 and 1979 oil price spikes triggered by the wars and revolutions in the Middle East. A few countries, including the USA and the UK, had smaller inflation bursts in 1990. But since then, inflation has remained steadily low in all OECD countries, with several countries experiencing episodes of price declines, especially in the aftermath of the global financial crisis of 2008. INCREASED CENTRAL BANK CREDIBILITY The downward trend and stabilization of inflation across the developed world over the past few decades can be partially attributed to the increased credibility of the main central banks’ commitment to a low inflation regime. Inflation was finally crushed in the early 1980s, when central banks raised interest rates to whatever level was required to achieve price stability. 1 See, for example, Feldstein Martin (2009), “Inflation is looming on America’s horizon”, Financial Times, April 19, or, Allan H. Meltzer (2009), “Inflation nation”, Financial Times, May 3. 2 See notably Paul Krugman (2014), “Inflation targets reconsidered”, Draft Paper for the ECB Sintra conference, May. 2 ECONOTE | No. 30 – MARCH 2016 BOX 1. THE GREAT INFLATION The high inflation that occurred between the mid-1960s and the early 1980s, which is commonly known as the “Great Inflation”, was a defining moment of macroeconomic history. Some have characterized these high-inflation decades as “the greatest failure of American macroeconomic policy in the post-war period” [see Mayer (1999)3]. Explanations for the Great Inflation fall roughly into three main categories: The bad luck view. The first type of explanations emphasizes supply shocks and the subsequent demand response4. The unprecedented rise in commodity prices (mainly food and oil) in 1973-74 and again in 1979-80 definitely played an important role in the Great Inflation. However, the temporary burst of price inflation from the oil shocks could only affect the course of the long-run inflation trend to the extent that it was followed by endogenous adjustment of the private sector and policy authorities, with central bankers accommodating the increase in wage bargainers’ expectations of inflation (that is, wage-cost push inflation). The monetary policy neglect view5. The second class of explanations emphasizes policymakers’ belief in an exploitable Phillips curve trade-off, that is, the notion that policymakers could choose to permanently reduce the unemployment rate by accepting a permanently higher inflation rate6. According to this view, the rise in inflation from the mid-1960s through the early 1980s reflected a shift to a higher inflation target. Eventually, however, policymakers became convinced that there was no long-run trade-off, as inflation rose hand in hand with unemployment - a combination known as “stagflation”. As a result, they started raising interest rates to fight inflation. The policy mistakes view7. The third class of explanations stresses that policymakers in the 1970s overlooked a break in the economy’s productive potential (or potential output8) and a rise in the so-called “natural” rate of unemployment (or the level of unemployment consistent with a constant rate of inflation, often called the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment or NAIRU - see Box 3). This led them to be excessively optimistic about how low the unemployment rate could go before igniting inflation pressures (that is, they severely underestimated the NAIRU). Natural rate misperceptions caused monetary policies to become overly expansionary, ultimately resulting in high inflation9. While these different views vary in their emphasis on the main causes of the Great Inflation, they all share a common factor, i.e. monetary policy in the 1970s was, in retrospect, excessively expansionist. 3 Mayer, Thomas (1999), “Monetary Policy and the Great Inflation in the United States: the Federal Reserve and the Failure of Macroeconomic Policy, 1965-1979”, Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar. 4 See, for example: Blinder, Alan S. (1982), “The Anatomy of Double-Digit Inflation in the 1970s”, In Inflation: Causes and Effects, ed. R. Hall, pp. 261-282. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 5 The label is from Nelson, Edward, and Kalin Nikolov (2002), “Monetary Policy and Stagflation in the UK”, Bank of England Working Paper N°.155, May. On this strand of explanations, see, notably: Barro, Robert J. and David B. Gordon (1983), “A Positive Theory of Monetary Policy in a Natural Rate Model”, Journal of Political Economy, XCI, pp.589-610. 6 See Phillips, A. W. H. “The Relation Between Unemployment and the Rate of Change of Money Wage Rates in the United Kingdom, 1861–1957.” Economica, n.s., 25, no. 2 (1958): 283–299. The empirical inverse relationship between unemployment and wages that Phillips highlighted for the British economy up to WW1 encouraged many economists, following the lead of Paul Samuelson and Robert Solow, to treat the so-called Phillips curve as a sort of menu of policy options between inflation and unemployment. See Samuelson, Paul A., and Robert M. Solow (1960), “Analytical Aspects of Anti-inflation Policy”, American Economic Review 50, May, no. 2, pp.177–194. 7 See, for example: Cukierman, Alex and Francesco Lippi (2002), “Endogenous Monetary Policy with Unobserved Potential Output”, Tel Aviv University; Cogley, Timothy and Thomas J. Sargent (2001), “Evolving Post-World War II U.S. Inflation Dynamics”, in NBER Macroeconomic Annual, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, pp.331-373. 8 The “potential output” is the level of output that can be produced and sold without creating pressure for the rate of inflation to rise or fall. 9 During the 1960s, there was a consensus that the natural rate of unemployment in the United States was about four percent. But the natural rate rose in an unexpected way during the 1970s because of a large influx of new workers from the baby boom and women entering the workforce, as new workers tend to have high frictional unemployment rates (one of the two components of the natural rate). With actual unemployment rising during and after the recession that started at the end of 1969, and knowing that policymakers were underestimating the natural rate, it was only natural to hold the view that the economy was operating with considerable slack, which led the Fed to pursue aggressive monetary policy to bring the unemployment rate down. 3 ECONOTE | No. 30 – MARCH 2016 When Paul Volcker stepped in, in late 1979, inflation control became the overriding objective of monetary policy to the detriment of the employment objective. The primacy of price stability was then accepted by central bankers worldwide, and many governments institutionalized their commitment to inflation control with the creation of independent central banks. The resulting shift toward a more restrictive monetary policy regime provided the anchor for inflation expectations that had been missing since the collapse of the Bretton Woods system10. Expectations of future inflation are important determinants of current inflation, but they exhibit a great deal of inertia. So establishing credibility in the fight against inflation is crucial to defeating inflation. It took a few years for inflation to come down after Volcker’s decision to raise interest rates to double-digit figures (the so-called 1979 Volcker Shock), as the public was initially slow to accept the primacy of the inflation objective. But as the Fed stuck to its painful and unpopular policy of monetary restraint long enough to demonstrate its commitment to low inflation (which caused the economy to fall into recession and the monthly unemployment rate to surge to 10.8%, a level unseen since the Great Depression), the belief in its inflation aversion ultimately became entrenched, and the inherent inflation momentum finally reversed. Since the early 1980s, the stronger commitment by central banks to maintaining a low and stable rate of inflation has been remarkably successful at keeping inflation expectations anchored, which has removed an inflationary bias that some have blamed for the high inflation of the 1970s. POSITIVE SUPPLY SHOCKS Though central banks have claimed credit for the disinflation that followed Volcker’s monetary squeeze 10 The collapse of Bretton Woods encompasses the events that occurred between 1968 and 1973 and which led to the suspension of the dollar’s convertibility into gold. By March 1973, the unified fixed exchange rate regime had collapsed, and the major currencies were floating against each other. and the low inflation that characterized the postVolcker years, the role played by the combination of globalization and the spread of technological innovation should not be overlooked. Over the past few decades, globalization, along with a wave of technological innovation, has buffeted the world economy with positive supply shocks that have to-date exerted constant downward pressure on prices. The success of GATT negotiations to remove trade barriers has typically resulted in lower prices for imported goods and thus provided competitive discipline for domestic firms. Deregulation combined with expanding globalization has sharply increased competition and lowered monopoly pricing power, while making it more difficult for advanced economies to avoid disinflationary impulses from abroad. Meanwhile, the entry of China and other major emerging countries, such as India, into the global trading system has profoundly changed how economic processes work, especially regarding the bargaining outcomes between buyers and sellers. The spread of new information and communications technologies (ICTs) has greatly improved the speed, quality and accessibility of information flows at negligible marginal cost, leading to heightened competition between suppliers and retailers. And the faster and wider spread of advanced production techniques and cost-reducing technologies through foreign direct investment (FDI) has included the beneficial effect of promoting productivity and output growth. There was a revival of productivity in many countries during 1995-2004, which contributed to holding unit labour costs down. Rising productivity, combined with declining import prices and low oil prices, led to substantial downward pressure on inflation. Meanwhile, nominal wages remained subdued, in large part because of the integration of China’s massive labour force into the world economy. This profoundly changed the balance of power between employers and employees throughout the developed world. The consequent rise in the global labour supply, coupled with increased competition and the threat of delocalization of whole factories to lower-cost countries eroded the power of organized labour and 4 ECONOTE | No. 30 – MARCH 2016 constrained rises in labour compensation. Meanwhile, rapid advances in automation technology lowered the demand for workers in low-skilled jobs, putting downward pressure on their wage rates. This has contributed to lowering labour’s share of income in many developed countries (with the notable exception of France) over the past 25 years11. An increasing part of the labour share of GDP has gone to the highest earners, leading to mounting income inequality. excessively lax over the past few decades, as the main central bankers have increasingly found themselves resisting “good” structural disinflationary pressures. White (2015) argues that the US monetary policy stance has been systematically too expansionary since 1987. The stock market crash of October 1987 prompted the Federal Reserve to lower the federal funds rate by 50 basis points and opened an era in which the Fed, under Chairman Greenspan, came up with a rescue package whenever a major crisis arose (i.e. the 1990-1991 recession, the collapse of LongTerm Capital Management, The Asian Contagion, the bursting of the dotcom bubble and the aftermath of the September 11 attacks)13. There have been many cycles of monetary easing since 1987, but they have not been matched with equal monetary tightening cycles during the “good” times. This has caused policy interest rates to fall towards zero and, in several countries, all the way to the zero lower bound. Low interest rates, in turn, have led to a sharp rise in private debt and a surge in housing prices and in certain financial assets14. THE GREAT MODERATION By 2000, inflation had fallen to around 2% in many countries of the world and it remained stable for many years. From the mid-1980s to 2007, the economy appeared to have entered another distinct phase in which the level and volatility of the inflation trend and output declined significantly (a phenomenon which came to be known as the “Great Moderation”). The Great Moderation has been attributed to a combination of factors including well-anchored inflation expectations, primarily due to improved monetary policy performance (greater independence, better communication strategies, etc.), structural changes in labour and goods markets and good luck. Economists, however, differ on what roles were played by the different factors in contributing to the decline in trend inflation during that period. The reason, of course, is that determining the relative importance of structural factors (which set the intensity of cost-push effects) and cyclical factors (which determine the intensity of demand-pull effects) in price setting is far from straightforward. Some [see, for example, White (2015)12] have argued that the deflationary pressures stemming from economy-wide positive supply shocks have been misinterpreted as “bad” deflation. As a consequence, monetary policy in the developed world has been NEGATIVE DEMAND SHOCK SINCE 2008 The calm of the Great Moderation ended abruptly with the global financial crisis of 2007-08. The ensuing crash of the credit-fuelled boom prompted a cycle of forced deleveraging of the debt-laden private sector. This created a massive negative shock to aggregate demand, plunging the developed world into the Great 13 During the Greenspan era (1987-2006), the provision of ample emergency liquidity whenever financial crises came to a head created the perception that a dramatic decline in asset prices would always prompt the Fed to come riding to the rescue of stock investors (if not to stock investors themselves, to the threat to the economy that would arise from a stock market crash) to avert further losing positions. This gave investors the confidence that the Fed would always take decisive action to stem an escalating financial crisis - a belief that has become known as the “Greenspan put”. 11 See, for example, Elsby, Michael, Bart Hobijn, and Aysegül Sahin (2013), “The decline of the U.S. labor share”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Fall. 12 William R. White (2015), “On the need for greater humility in the conduct of monetary policy”, Remarks to VAC Munich on the occasion of receiving the Hans-Möller-Medal for 2015, May. 14 The BIS has long argued that monetary policy-making has been dangerously asymmetric, as central bankers have failed to lean against the booms, while they have eased aggressively and persistently during busts. This, it is argued, has created something akin to a debt trap, where it is difficult to raise rates without damaging economic growth. 5 ECONOTE | No. 30 – MARCH 2016 Recession. Inflation slowed sharply as the world’s advanced economies went into a deep recession. In 2010-2011, almost all euro zone countries entered a period of fiscal tightening which amplified the negative demand shock created by the unwinding of accumulated financial imbalances. In 2011, inflation rose above the main central banks’ official 2% inflation target as global oil prices surged; however, the spike in inflation was certainly not dramatic. Since 2012, inflation has dropped well below 2%, reflecting the collapse in oil and commodity prices since the summer of 2014 as well as wage stagnation and enduring weak aggregate demand. Over the last few years, core inflation (excluding volatile food and energy prices) - central bankers’ preferred measure – has been running below the 2% target in the majority of advanced economies15. DESPITE MANY PREDICTIONS TO THE CONTRARY, INFLATION HAS FALLEN TO RECORD LOWS But, since 2008, central banks have injected huge sums of money into their banking systems and maintained their short-term nominal interest rates at virtually zero. Meanwhile, governments have run large fiscal deficits. Yet, despite many predictions to the contrary, this has not had any material effect on inflation. Why? The reason is that much of the developed world has, in fact, fallen into a liquidity trap17. An economy is in a liquidity trap when the zero short nominal interest floor becomes a binding constraint. Once interest rates are zero, economic agents become indifferent about holding money and holding bonds, and their demand for liquidity becomes virtually endless. So banks prefer to hold excess reserves instead of extending loans and people prefer to hoard money rather than spending it. The result is a fall in the velocity of money circulation (the rate at which money changes hands) which offsets central banks’ injection of money, preventing monetary policy from gaining traction in the real economy. THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE MONEY SUPPLY AND INFLATION DOES NOT HOLD IN A LIQUIDITY TRAP As the Great Recession set in, the world’s main central banks slashed their policy interest rates to virtually zero in an effort to stimulate their economies and fight against deflationary pressure. Once they hit the zero bound on policy rates, the main central banks then resorted to large-scale purchases of longer-term private or public bonds – a process known as quantitative easing (QE) – in order to give a further stimulus to the economy. QE swelled the central banks’ balance sheets dramatically. Yet QE has always been a contentious policy tool. Its critics warned of runaway inflation and risks of financial bubbles16. liquidity injected would migrate towards financial markets, thus fuelling inflation in financial markets. See notably Borio, Claudio, and Piti Disyatat (2009), “Unconventional monetary policies: an appraisal”, BIS Working Papers n°292, November. Also see Claudio Borio (2015), Media briefing on the BIS Annual Report 2015, 24 June. 17 15 The Fed uses the core Personal Consumption Expenditures (or PCE) Index – which measures actual household spending - as its yardstick. 16 Many critics worried that QE would contribute to excessive leverage and risk-taking in financial markets and that most of the Keynes invented the concept of the liquidity trap. See Keynes, John M. (1936), The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, Macmillan. To cite him: “There is the possibility... that after the rate of interest has fallen to a certain level, liquidity preference is virtually absolute in the sense that almost everyone prefers cash to holding a debt at so low a rate of interest. In this event, the monetary authority would have lost effective control”. 6 ECONOTE | No. 30 – MARCH 2016 BOX 2. MONETARISM FALTERS IN A LIQUIDITY TRAP The classical theory of inflation, called monetarism, maintains that the money supply is the chief determinant of price level over the long run. Monetarism is mainly associated with Nobel Prize-winning economist Milton Friedman who famously wrote that “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon”18. Monetarism came into vogue in the 1970s, and greatly influenced the US central bank’s decision to abruptly tighten monetary policy to tame inflation in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The foundation of monetarism is the Quantity Theory of Money. The theory is an accounting identity, which says that the money supply, M, multiplied by the velocity of circulation of money, V, equals the general price level, P, multiplied by the real economic output (or the total quantity of goods and services produced), Q: M*V=P*Q. As an accounting identity, the quantity theory of money is always true and thus uncontroversial. The controversy arises because monetarists make the assumption that velocity (V) is relatively stable over time, or at least predictable, which means that changes in the money supply (M) are the dominant forces that change nominal GDP (P*Q). Moreover, monetarists believe in long-run monetary neutrality, meaning that in the longer term real variables, like real output, real consumption expenditures, real wages and real interest rates, are unaffected by changes in the money stock, even though, they reckon, real output (Q) may vary in the short run due to wage- and price-stickiness (as wages and prices take time to adjust). So, monetarists believe that the money supply is the primary determinant of nominal GDP in the short run and of the price level in the long run. In the 1970s, the velocity of the money supply M1 in the USA increased at a fairly constant rate, which seemed to vindicate the short-run monetarist theory views (i.e. that the rate of growth of the money supply, adjusted for a predictable level of velocity, determined nominal GDP). However, since the 1980s, the velocity of money has exhibited high and unexpected shifts19 and since the second quarter of 2008 it has collapsed. In October 2015, velocity was at 5.9, meaning that every dollar in the monetary supply was spent only 5.9 times in the economy, down from 10.7 just prior to the 2008 recession. The collapse in the velocity of money since the Great Recession has almost entirely offset the unprecedented monetary base increase driven by the Fed’s large money injections through its large-scale asset purchase programs. As a result, nominal GDP (either P or Q) has hardly changed. When an economy is in a liquidity trap, the relationship between the money supply and nominal GDP falls apart20. 18 See Milton Friedman (1956), “The Quantity Theory of Money: A Restatement” in Studies in the Quantity Theory of Money, edited by M. Friedman. Reprinted in M. Friedman The Optimum Quantity of Money (2005), pp. 51-67. 19 The unstable behavior of the velocity of money in the 1980s primarily reflected changes in banking rules and financial innovations. In the 1980s banks were allowed to pay explicit interest on deposits, which led many people to hold their wealth in the form of interest-earning checking accounts rather than in savings accounts, hence, a major and unexpected rise in the demand for money at banks. Moreover, financial markets began introducing financial instruments (e.g. mutual funds) that competed with traditional bank deposits, so some people shifted their funds to those instruments, which also weakened the link between the money supply and nominal GDP. 20 See, for example, Maria A. Arias and Yi Wen (2014), “The liquidity trap: an alternative explanation for today’s low inflation”, in The Regional Economist, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, April; Maria A. Arias and Yi Wen (2014),”What does money velocity tell us about low inflation in the US”, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, September 1; David C. Wheelock (2010), “The monetary base and bank lending: you can lead a horse to water…”, In Economic Synopses, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Number 24. 7 ECONOTE | No. 30 – MARCH 2016 Economies in a liquidity trap require either deeply negative nominal interest rates, which is virtually impossible given the zero (or near zero) lower bound on interest rates, or much higher inflation expectations, which is the only way left to bring about the fall in real interest rates that the economy would need to perform at potential or at full employment. The problem, however, is that it is very hard to induce expectations of a higher future price level when the economy is stuck at the zero lower bound. THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN UNEMPLOYMENT AND INFLATION REMAINS UNCERTAIN Nevertheless, the Federal Reserve, at its December meeting, was reasonably confident that inflation would rise to its 2% target by 2018, which paved the way for the Fed’s first rate hike since December 2008. On December 16, the target range for the federal funds rate was raised from 0-0.25% to 0.25-0.50% (still very close to zero). Federal Reserve officials expect to slowly ratchet their benchmark short-term interest rate to above 3% in three years. A key argument in favour of raising the benchmark interest rate was to overcome the binding constraint on the effectiveness of monetary policy that the zero lower bound is imposing. Higher rates would give the Federal Reserve room to lower interest rates when it needs to fight the next recession. The risk of course, is that a premature increase in nominal interest rates could lower inflation expectations and thus raise real interest rates and stifle economic growth. Another factor which played a role in the Fed’s decision to begin a new cycle of monetary tightening was the improvement in the labour market and its implications for inflation down the road. At 5% in December 2015, the US unemployment rate is at the level the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) thinks is consistent with stable inflation. The usual assumption is that inflation and unemployment move in opposite directions, as suggested by the so-called Phillips curve. Today, a revised version of the Phillips curve, called the New Keynesian Phillips curve, is used by economists to forecast inflation. Typically, the likely path of future inflation will depend on expected inflation and on a measure of slack, i.e. the gap between current unemployment and the natural rate of unemployment (or NAIRU). The problem, though, is that the Phillips curve model appears to have great difficulty accounting for the fact that over the past two decades, across much of the developed world, the core inflation rate has fluctuated within a narrow range despite substantial volatility in unemployment. This has led many economists to wonder whether the Phillips curve relationship has fallen apart21. 21 See, for example, Krugman, Paul (2014), “Inflation, Unemployment, Ignorance”, The New York Times Blog, July 28. 8 ECONOTE | No. 30 – MARCH 2016 BOX 3. THE NATURAL RATE OF UNEMPLOYMENT The “natural rate” of unemployment, which is often called the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment or NAIRU, is a theoretical concept independently developed by Edmund Phelps22 and Milton Friedman23. The natural rate is defined as the rate of unemployment at which there is no tendency for inflation to accelerate or decelerate. It is determined by several labour market imperfections. The natural rate is a combination of frictional and structural unemployment24 which exist even if the economy is running at full capacity and close to its long-run potential growth rate. It is not constant, but changes over time. And as it is not directly observable, it has to be estimated. The natural rate hypothesis came to the fore in the mid-1970s when both inflation and unemployment rose simultaneously, which the Friedman-Phelps model had predicted. For Friedman and Phelps, a tradeoff between inflation and unemployment could only be achieved by tricking people about inflation and thus could only exist in the short term. In this model, monetary stimulus used to lower unemployment below its natural rate can only lead to accelerating inflation. As worker inflation expectations catch up with reality, rational workers demand greater nominal wages so that their incomes will keep pace with inflation. As real wages rise, firms cut back on their hiring and unemployment rises back to its previous level, but with higher inflation reflecting a tight labour market and bottlenecks in production. In the Friedman-Phelps model, the inflation-unemployment tradeoff disappears over the long term, as the unemployment rate returns to its natural rate, regardless of the inflation rate, resulting in a vertical, long-term Phillips curve. The analysis made by Friedman and Phelps can be summarized as follows: Unemployment rate = natural rate of unemployment – p*(actual inflation - expected inflation) Where p is a variable which measures how much unemployment responds to unexpected inflation. In the short term, expected inflation is a given, so higher actual inflation is associated with lower unemployment. But in the longer term, when expected inflation has fully adjusted to actual inflation, the unemployment rate stands at a level uniquely consistent with a stable inflation rate—the natural rate of unemployment or NAIRU. While monetary stimulus cannot decrease unemployment in the long run, microeconomic policies can lower the NAIRU itself by removing labour market imperfections. In the aftermath of the stagflation of the 1970s, theories based on the natural rate of unemployment largely displaced the earlier view that a permanent tradeoff existed between inflation and unemployment. The idea that there was no long-run relationship between inflation and unemployment became the paradigm in monetary economics. As the belief in a short-run tradeoff between inflation and unemployment continued to prevail, estimating the NAIRU became part of the core business of central banks25. 22 Phelps, Edmund S. “Phillips Curves, Expectations of Inflation and Optimal Employment over Time.” Economica, n.s., 34, no. 3 (1967): 254–281. 23 Friedman, Milton. “The Role of Monetary Policy.” American Economic Review 58, no. 1 (1968): 1–17. 24 “Frictional” unemployment occurs because finding a job takes time while “structural” unemployment arises from various factors such as skill mismatch, location mismatch, institutional barriers (minimum wage laws, etc.), imperfect information flows or public transfer programs (which reduces the incentive to search for a job). 25 See e.g. Laurence Ball, N. Gregory Mankiw, and David Romer (1988), “The new Keynesian economics and the output-inflation tradeoff”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 19, pp.1-82. 9 ECONOTE | N°30 – MARCH 2016 So the hot question currently being debated in the USA is if inflation will start to increase soon given that the economy is entering the NAIRU zone26. So far, wage pressures in America have remained subdued, contributing to keeping core inflation (excluding the transitory effects of supply shocks) in check. At this point, there are few signs that rising wages will soon start to push inflation higher in the US or most other developed countries. The lack of meaningful wage growth is evident in the great majority of developed countries despite a declining unemployment rate in many countries. Real wages for most workers continue to stagnate or fall across the developed world. Some analysts believe that, with unemployment at the NAIRU, wage growth and inflation in America is about to start accelerating27. Yet others argue that this remains subject to large uncertainties. The question of whether there is still slack in the labour market remains indeed a matter of considerable debate. While some believe that the slack in the US labour market has been eliminated, others contend that the decline in the unemployment rate masks continued weakness. The latter emphasize, in particular, falling labour force participation – down from 66% in July 2008 to 62.9% in February 2016 – or the large number of part-time workers, while arguing that people who have left the formal workforce but still want a job, or people who would like a full-time job but can only find part-time work, may hold down wages by enhancing competition among job seekers28. Quite apart from that, many analysts point out the structural shifts that have taken place in the labour market in recent decades to argue that wage growth will remain sluggish for the foreseeable future across much of the developed world. Arguably, the diminished influence of organized labour (owing to increased global competition and/or legal reforms), as well as the rising flexibility in the labour market (with a rising share of part-time, temporary and zero-hours contracts) will keep bearing down on wage growth in the years ahead. These trends have created an environment which is very different from that which generated cost-push inflation in the 1970s by making it much easier to restrain pay raises. This has been reflected in a declining labour share of GDP in the United States, as wages have not been improving in line with productivity. The decline in labour productivity growth that has been observed in many developed countries since 2008 has only made matters worse. 27 26 For a summary of the argument see notably Gavyn Davies (2016), « Splits in the Keynesian camp: a Galilean Dialogue », Financial Times, February 21. So the argument goes that as idle labour becomes scarce, firms will raise wages to attract scarce labour, which will push consumer prices higher, as businesses act to protect their profit margins given that wages are a significant fraction of their production costs. 28 See, for example, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta (2014), “Jobs: More work to be done?”, Annual Report. 10 ECONOTE | N°30 – MARCH 2016 BOX 4. THE “MISSING DEFLATION PUZZLE” The debate over the relevance of the Phillips curve has gained momentum since the Great Recession, as inflation has not fallen as much as the standard Phillips curve model predicts29. Given the surge of unemployment to high levels, the model typically predicts deflation, but most developed countries have exhibited low core inflation, rather than deflation, hence the so-called “missing deflation puzzle”30. This has led a number of observers to wonder whether the Phillips curve relationship has in fact broken down. Many economists have put forward possible explanations for why most advanced economies have not seen deflation since 2008. Three basic ideas have stood out, leading to revised versions of the Phillips curve. The first idea is that inflation expectations have become well-anchored, owing mainly to central bank credibility31. The argument is that the central banks’ inflation target of 2% has kept expected inflation near 2% which has prevented actual inflation from falling far below that level. The second idea is that the short-run rate of unemployment is a better predictor of inflation than the aggregate unemployment rate (used in the typical Phillips curve)32. This is because, the argument goes, the long-run unemployed do not put downward pressure on wages, either because they do not search intensively for work or because employers tend to view them as “unemployable”. During the Great Recession, short-term unemployment rose less sharply than total unemployment and has since returned to pre-recession levels. Gordon (2013) hypothesized that the rising importance of long-run unemployment (spells of 27 weeks or more) has caused the NAIRU in the US to rise - from 4.8% in 2006 to 6.5% in 2013 –, suggesting that the labour market may be operating with less slack than is generally assumed, hence the lack of deflation as well as the nascent inflation threat. The suggestion that only the short-term unemployment rate matters for wage determination has been gaining increasing attention in policy circles. The third idea is that most advanced economies exhibit downward nominal wage rigidity due to great resistance to cuts in nominal pay, and that this has prevented inflation from falling into negative territory. Daly and Hobijn (2014) argued that, during recessions, downward nominal wage rigidities become more binding, leading to disproportionate adjustment through unemployment rather than through wages33. 29 This followed the failure of the traditional Philip’s curve to explain the positive relationship between inflation and unemployment in the mid-1970s and the decline in inflation despite low unemployment in the 1990s. 30 See notably Laurence Ball and Sandeep Mazumder (2011), “Inflation Dynamics and the Great Recession”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity (Spring), pp.337-381. 31 See notably Bernanke, B. (2010), “The economic outlook and monetary policy”, Speech at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Economic Symposium, Jackson Hole, Wyoming, and International Monetary Fund (2013), “The dog that didn’t bark: Has inflation been muzzled or was it just sleeping?”, World Economic Outlook. Also see Laurence Ball and Sandeep Mazumder (2015), “A Philips curve with anchored expectations and short-term unemployment”, IMF Working Paper WP/15/39, February. 32 See Robert J. Gordon (2013), “The Philips curve is alive and well: Inflation and the NAIRU during the slow recovery”, National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper n°19390, August. Also see Krueger, A., T. Cramer and D. Cho (2014), “Are the long-term unemployed on the margins of the labour market?”, Brookings Panel on Economic Activity, March; Watson, M. W. (2014), “Inflation persistence, the NAIRU and the Great Recession”, American Economic Review (Papers and Proceedings), May; Linder, H. M., R. Peach and R. Rich (2014), “The long and short of it: The impact of unemployment duration on compensation growth”, Liberty Street Economics, Federal Reserve Bank of New York. 33 See notably Daly, Mary C. and Bart Hobijn (2014), “Downward nominal wage rigidities bend the Philips curve”, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Working Paper 2013-08, January. 11 ECONOTE | N°30 – MARCH 2016 policy rates substantially below zero36. Low inflation exacerbates the problems posed by these two lower bounds. Another reason why wage gains may remain slow and fragile for a while lies in “pent-up wage deflation”34. Daly and Hobijn (2014) argued that firms, which were generally unable to cut wages during the Great Recession, later compensated by withholding raises during the recovery35. The argument states that, during recessions, downward nominal wage rigidities imply that wage inflation remains higher than the rate that would occur if nominal wage levels were fully flexible and could be reduced, hence the emergence of substantial pent-up wage deflation. As the economy recovers, and unemployment falls, the downward pressure on wages diminishes. But the stockpile of pent-up wage deflation accumulated during the recession must be disposed of before the labour market can return to equilibrium. As long as the pool of wage cuts is not entirely exhausted, firms will wait for inflation and productivity growth to bring wages closer to their desired level rather than raise nominal wages. So, during that period, wage growth remains low even though the unemployment rate is declining. Downward nominal wage rigidity causes the short-term Phillips curve to flatten [see Daly and Hobijn (2014)]. The big question now is, at what stage of the adjustment process are we? THE ECONOMICS OF LOW INFLATION Low inflation increases rigidity in the labour market37. Evidence of the great resistance to cuts in nominal wages, even in recessionary periods with very high unemployment, abounds across much of the developed world. Sticky nominal wages, coupled with low inflation, mean that higher-than-desired real wages further reduce the demand for workers, contributing to higher and more enduring unemployment than would occur if inflation were, say, 3-4 percent. This is because a certain amount of inflation “greases the wheels” of the labour market as workers are typically less opposed to the erosion of their real wages by inflation. As Tobin (1972) pointed out38, downward nominal wage rigidity at very low rates of inflation implies a Phillips curve that is not vertical, even in the long run. This suggests that the rate of inflation may in fact have a lasting influence on the rate of permanent employment at which the economy eventually settles. Very low inflation in a sticky-wage world may cause permanently high unemployment, which may, in turn, prevent workers from obtaining higher wages. Low inflation also constrains real interest rates in a crucial manner. As seen above, the nominal interest rate cannot fall much below zero because that would THE PROBLEM OF THE TWO ZERO LOWER BOUNDS Is the developed world about to return to normality, with declining unemployment leading to sustained wage inflation eventually triggering central-bank interest-rate hikes? This appears highly unlikely. Part of the reason lies in two (not absolute) zero lower bounds, namely, the great difficulty of cutting nominal wages and the impossibility for central banks to reduce their 34 The term was coined by Daly, Mary C. and Bart Hobijn (2014) (op. cit. note 28). 35 Daly, Mary C. and Bart Hobijn (2014) (op. cit. note 28). Also see Daly, Mary C. and Bart Hobijn (2015), “Why is wage growth so slow?”, Economic Letter, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, January 5. 36 See notably Krugman, Paul (2014), “Lowflation and the two zeroes”, The New York Times Blog, March 5. Also see Krugman, Paul (2013), “Not enough inflation”, The New York Times Blog, May 2, 2013. 37 See Akerlof G.A, Dickens WT, Perry WL (1996), “The macroeconomics of low inflation”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 1, pp.1-75; Akerlof G.A, Dickens WT, Perry WL (2000), “New rational wage and price setting and the long-run Phillips curve”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 1, pp.1-60; Dickens, WT. (2010), “Has the recession increased the NAIRU?”, mimeo, Northeastern University; Schmitt-Grohe, S. and M. Uribe (2012), “The making of a Great Contraction with a liquidity trap and a jobless recovery”, NBER Working Paper n°18544. 38 Tobin James (1972), “Inflation and unemployment”, American Economic Review 62, pp.1-18. 12 ECONOTE | N°30 – MARCH 2016 prompt people to withdraw their deposits from banks and sit on cash hoards. Together with low inflation, this means that there is no room left for monetary policy to reduce interest rates in the face of adverse demand shocks. So, low inflation increases the probability that the effective lower bound on nominal interest rates will bind and, thus, enhances the risk that the real interest rate may not be able to fall far enough to generate sufficient aggregate demand to allow the economy to perform at potential. Today, seven years after the onset of the Great Recession, the still-wide negative output gaps that much of the developed world exhibits is testimony to the enduring shortfall of aggregate demand. The failure of the real interest rate to fall to its equilibrium value induces a chronic shortage of aggregate demand which may cause the economy to remain stuck in stagnation for an indefinite length of time. THE DEBT OVERHANG PROBLEM Another challenge from very low inflation arises from Fisher-type debt deflation. Fisher (1933) famously argued that sustained deflation can be highly destructive to the economy because it worsens the balance sheets of debtors by increasing the real burden of their debt. This can set off a selfperpetuating feedback loop between falling inflation, rising debt burdens and weakening spending39. Moreover, deflation redistributes income from debtors to lenders, but as lenders have a higher propensity to save than debtors, the result is that demand growth is further sapped overall. Importantly, these Fisherian debt deflation mechanisms are not only triggered by outright deflation, but can also arise when inflation is running below expectations, as shown by the IMF (2014)40. This perverse loop between debt and low inflation has undoubtedly been a substantial factor behind the slow and painful deleveraging process the developed world has experienced in the aftermath of 39 Fisher, Irving (1933), “The debt-deflation theory of Great Depressions”, Econometrica, 1(4). 40 See Moghadam, Reza, Ranjit Teja and Pelin Berkmen (2014), “Euro area – 'Deflation' versus 'Lowflation'", IMF Direct, March 4. the global financial crisis. These vicious effects are, of course, more intense in a deflationary world than in a low-inflation environment. Japan’s experience with deflation has so far turned out to be pretty much unique, thanks to well-anchored inflation expectations and sticky nominal wages in most developed countries41. Could collapsing oil prices upset this state of affairs? With inflation already close to zero, falling oil prices often causes inflation to fall below zero. But, conversely, it gives extra purchasing power to importing countries, which can stimulate demand. It is however possible that these positive demand effects are slower to materialize than during previous oil counter-shocks: because of past excesses private agents may have indeed a tendency to use this extra purchasing power to deleverage more quickly instead of spending more. TODAY THE DANGER ARISES FROM TOOLOW INFLATION INFLATION AND DEFLATION: FROM ONE EVIL TO ANOTHER? The conventional macroeconomic wisdom of the past few decades was that high and variable inflation has costs. These costs stem largely from the fact that inflation erodes the purchasing power of money and redistributes income haphazardly. However, Barro (1997) – in one of the most influential studies in this body of literature – found that, based on a panel of about 100 countries between 1965 and 1990, there was no evidence that inflation rates below 10-15% 41 It is worth emphasizing that, although downward nominal wage rigidity becomes a serious constraint if the relative wages of large groups of workers “need” (in a market-clearing sense) to fall, it has the beneficial effect of warding off destructive deflation. Sticky nominal wages may create supply-side difficulties if wages are stuck above the equilibrium wage rate thus, other things being equal, causing unemployment. But downward nominal wage rigidity also helps counter the risk of deflation, hence alleviating the aggregate demand problem stemming from debt deflation mechanisms. 13 ECONOTE | N°30 – MARCH 2016 were harmful for real growth42. Empirical research has yielded no conclusive findings regarding the quantification of the impact of inflation on economic performance [see, for example, Bernanke, Laubach, Mishkin and Posen (1999)43]. As for deflation, there is a distinction to be made between “good” and “bad” deflation. Good deflation typically arises from positive supply shocks (such as technological innovations) that cause aggregate supply to increase more rapidly than aggregate demand. When deflation reflects rapid productivity growth, as in the late nineteenth century, it can go hand in hand with rising real incomes and positive economic growth44. But that is in sharp contrast with the experience of deflation during the Great Depression or in Japan in the aftermath of its asset price bubble, when prices were falling because of a slump in aggregate demand. If deflation is caused by declines in aggregate demand that outpace rises in aggregate supply, it can have deleterious effects on the economy. This is because, in a deflationary environment, consumers and businesses tend to delay spending and investment decisions in anticipation that prices will continue dropping, which can lock economies into a downward spiral of demand and prices. Adding the fact that falling prices increase the real burden of existing debt and may prevent the central bank from pushing nominal interest low enough to close the gap between actual and potential output, deflation appears to be a sure-fire recipe for long-term economic stagnation and self-perpetuating low inflation. And as Japan has shown, once entrenched, deflation is hard to defeat. PENDULUM SWINGING TOWARDS FEAR are likely to be far smaller than the long-run costs of allowing inflation to rise to double or triple digits. This is why some observers argue today that inflation could become a danger if the Fed failed to respond adequately to the fall in unemployment. There are certainly few signs of a wage-price spiral today, but, so goes the argument, wages are a lagging indicator. If they wait too long, central bankers may find themselves “behind the curve” with regard to winding down the extraordinary amount of monetary stimulus as inflation returns. Then, before you know it, the spectre of 70s-style stagflation (or even Weimar hyperinflation) may be back. The pendulum tends to swing back and forth. The Great Depression of the 1930s imparted an inflationary bias to fiscal and monetary policy. Then, fighting inflation became the overwhelming priority in the wake of the Great Inflation of the 1970s, as deflation was the furthest thing from anyone’s mind. Now, the pendulum has swung back and we are again facing a deflation scare. The main danger today doesn’t come from inflation threatening to reach unacceptably high levels, but from excessively low inflation. OF DEFLATION The generation of policymakers who lived through the 1970s learned that inflation breeds great evil and that steps should be taken to prevent it from getting out of control. The prevailing orthodoxy among central bankers in the past forty or fifty years has been that the short-term costs of unemployment and lost output due to pre-emptive action to stem inflation in its incipiency 42 Barro, Robert (1997). Determinants of economic growth: A cross-country empirical study. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. 43 Ben Bernanke, Thomas Laubach, Frederic Mishkin, and Adam Posen (1999). Inflation targeting: Lessons from the international experience. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. 44 Borio et al (2015) found that, based on a panel of 38 countries over the past 140 years, the historical link between output growth and deflation was weak and derived largely from the Great Depression. According to these authors, the link between output growth and asset price deflations was stronger. See Claudio Borio, Magdalena Erdem, Andrew Filardo and Boris Hofmann (2015), “The costs of deflations: a historical perspective”, BIS Quarterly Review, March. 14 ECONOTE | N°30 – MARCH 2016 PREVIOUS ISSUES OF ECONOTE N°29 Low interest rates: the ‘new normal’? Marie-Hélène DUPRAT (September 2015) N°28 Euro zone: in the ‘grip of secular stagnation’? Marie-Hélène DUPRAT (March 2015) N°27 Emerging oil producing countries: Which are the most vulnerable to the decline in oil prices? Régis GALLAND (February 2015) N°26 Germany: Not a “bazaar” but a factory! Benoît HEITZ (January 2015) N°25 Eurozone: is the crisis over? Marie-Hélène DUPRAT (September 2014) N°24 Eurozone: corporate financing via market: an uneven development within the eurozone Clémentine GALLÈS, Antoine VALLAS (May 2014) N°23 Ireland: The aid plan is ending - Now what? Benoît HEITZ (January 2014) N°22 The euro zone: Falling into a liquidity trap? Marie-Hélène DUPRAT (November 2013) N°21 Rising public debt in Japan: how far is too far? Audrey GASTEUIL (November 2013) N°20 Netherlands: at the periphery of core countries Benoît HEITZ (September 2013) N°19 US: Becoming a LNG exporter Marc-Antoine COLLARD (June 2013) N°18 France: Why has the current account balance deteriorated for more than 20 years? Benoît HEITZ (June 2013) N°17 US energy independence Marc-Antoine COLLARD (May 2013) N°16 Developed countries: who holds public debt? Audrey GASTEUIL-ROUGIER (April 2013) N°15 China: The growth debate Olivier DE BOYSSON, Sopanha SA (April 2013) N°14 China: Housing Property Prices: failing to see the forest for the trees Sopanha SA (April 2013) N°13 Financing government debt: a vehicle for the (dis)integration of the Eurozone? Léa DAUPHAS, Clémentine GALLÈS (February 2013) N°12 Germany’s export performance: comparative analysis with its European peers Marc FRISO (December 2012) N°11 The Eurozone: a unique crisis Marie-Hélène DUPRAT (September 2012) N°10 Housing market and macroprudential policies: is Canada a success story? Marc-Antoine COLLARD (August 2012) N°9 UK Quantitative Easing: More inflation but not more activity? Benoît HEITZ (July 2012) 15 ECONOTE | N°30 – MARCH 2016 ECONOMIC STUDIES CONTACTS Olivier GARNIER Group Chief Economist +33 1 42 14 88 16 olivier.garnier@socgen.com Olivier de BOYSSON Emerging Markets Chief Economist +33 1 42 14 41 46 olivier.de-boysson@socgen.com Marie-Hélène DUPRAT Senior Advisor to the Chief Economist +33 1 42 14 16 04 marie-helene.duprat@socgen.com Ariel EMIRIAN Macroeconomic / CEI Countries +33 1 42 13 08 49 ariel.emirian@socgen.com Clémentine GALLÈS Macro-sectorial Analysis / United States +33 1 57 29 57 75 clementine.galles@socgen.com François LETONDU Macroeconomic Analysis / Euro zone +33 1 57 29 18 43 francois.letondu@socgen.com Aurélien DUTHOIT Macro-sectorial Analysis +33 1 58 98 82 18 aurélien.duthoit@socgen.com Juan-Carlos DIAZ-MENDOZA Latin America +33 1 57 29 61 77 juan-carlos.diaz-mendoza@socgen.com Marc FRISO Sub-Saharan Africa +33 1 42 14 74 49 marc.friso@socgen.com Régis GALLAND Middle East, North Africa & Central Asia +33 1 58 98 72 37 regis.galland@socgen.com Brenda MEDAGLIA Macro-sectorial Analysis +33 1 58 98 89 09 brenda.medaglia@socgen.com Emmanuel PERRAY Macro-sectorial analysis +33 1 42 14 09 95 emmanuel.perray@socgen.com Sopanha SA Asia +33 1 58 98 76 31 sopanha.sa@socgen.com Danielle SCHWEISGUTH Western Europe +33 1 57 29 63 99 danielle.schweisguth@socgen.com Isabelle AIT EL HOCINE Assistant +33 1 42 14 55 56 isabelle.ait-el-hocine@socgen.com Sigrid MILLEREUX-BEZIAUD Information specialist +33 1 42 14 46 45 sigrid.millereux-beziaud@socgen.com Simon TORTEL Publishing +33 1 58 98 79 50 simon.tortel@socgen.com Amine TAZI Macro-financial analysis / United States & United Kingdom +33 1 58 98 62 89 amine.tazi@socgen.com Simon TORTEL Central and Eastern Europe +33 1 58 98 79 50 simon.tortel@socgen.com Société Générale | Economic studies | 75886 PARIS CEDEX 18 http://www.societegenerale.com/en/Our-businesses/economic-studies Tel: +33 1 42 14 55 56 — Tel: +33 1 42 13 18 88 – Fax: +33 1 42 14 83 29 All opinions and estimations included in the report represent the judgment of the Economics Department of Societe Generale alone and do not necessary reflect the opinion of Societe Generale itself or any of its subsidiaries and affiliates. These opinions are subject to change without notice. It does not constitute a commercial solicitation, a personal recommendation or take into account particular investment objectives or financial situations. Although the information in this report has been obtained from sources which are known to be reliable, we do not guarantee its accuracy or completeness. Neither Societe Generale nor its subsidiaries/affiliates accept any responsibility for liability arising from the use of all or any part of this document. Societe Generale may both act as a market maker or a broker, and may trade securities issued by issuers mentioned in this report, as well as derivatives based thereon, for its own account. Societe Generale, including its officers and employees may serve or have served as an officer, director or in an advisory capacity for an issuer mentioned in this report. Additional note to readers outside France: The securities that may be discussed in this report, as well as the material itself, may not be available in every country or to every category of investors. 16