THE CONSISTENCY OF REPEATED WITNESS TESTIMONY

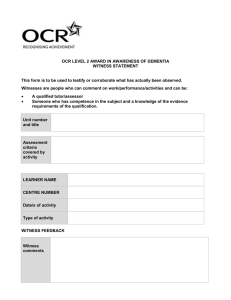

advertisement