arrested futures - American Civil Liberties Union

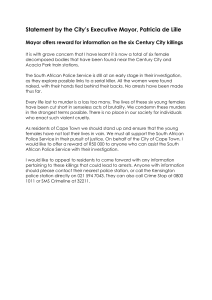

advertisement