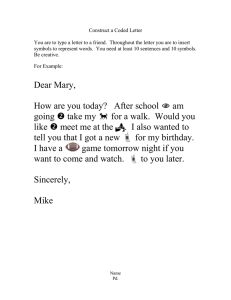

Active Symbols - Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School

advertisement