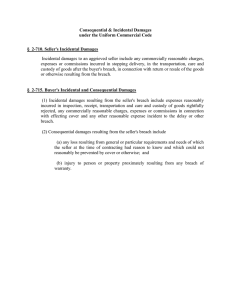

Recovery of Consequential Damages for Product Recall Expenditures

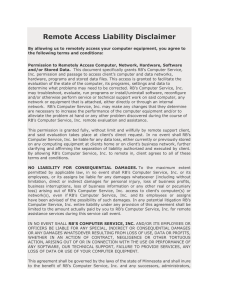

advertisement