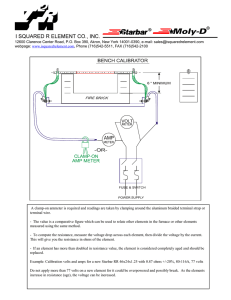

A SCREEN-GRID COUPLED DIRECT

advertisement