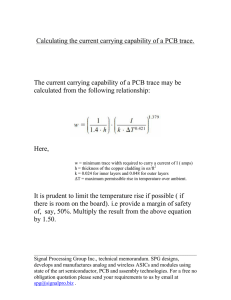

UNDP Project Document

advertisement