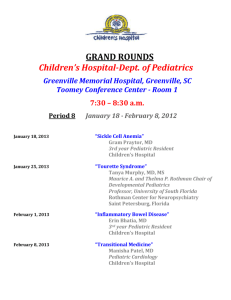

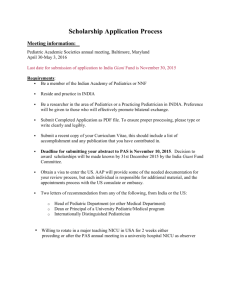

Hospital Pediatrics

advertisement