texas children`s hospital evidence-based clinical decision support

advertisement

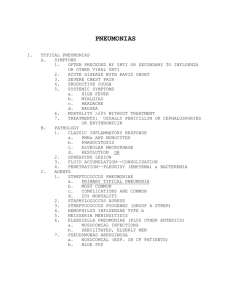

DATE: October 2008 TEXAS CHILDREN'S HOSPITAL EVIDENCE-BASED CLINICAL DECISION SUPPORT COMMUNITY-ACQUIRED PNEUMONIA (CAP) CLINICAL GUIDELINE Definition The presence of signs and symptoms of pneumonia in a previously healthy child, due to an infection of the pulmonary parenchyma that has been acquired outside of the (1) hospital. Etiology The exact etiology of pneumonia is often unidentified due to the difficulty of obtaining a direct culture of infected lung tissue. Following the introduction of Prevnar®, the burden of (1-2) invasive pneumococcal disease has been reduced. Currently, mixed etiologies account for 30 to 50% of the children with (1,3-5) community-acquired pneumonia. Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Chlamydia pneumoniae are more common in school-age (1) children. Viruses are most often identified in children < 5 years of age with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) being the most (1, 7-9) common viral etiology in children < 3 years of age. In the Southwestern United States data confirm the importance of Streptococcus pneumoniae and atypical pathogens (M. pneumoniae, C. pneumoniae) plus the frequent occurrence of mixed infections in children with community-acquired pneumonia. (10) In children with parapneumonic effusion at Texas Children's Hospital, Staphlyococcus aureus has become the most common (11) organism actually isolated. Differential Diagnosis Viral bronchiolitis Tuberculosis (TB) Pertussis Foreign body Guideline Eligibility Criteria Age ≥ 60 days to 17 years Healthy children without underlying conditions Clinical findings of CAP Guideline Exclusion Criteria Aspiration Recent hospitalization (< 7 days before the onset of illness) Diagnostic Evaluation Pneumonia related pathogens vary in incidence throughout the year but peak during January through (10) April in the Southwest United States. Pathogens currently circulating in the local community should be considered in the diagnostic evaluation. Physical Examination: The severity of pneumonia is based on overall clinical appearance and behavior, including a child’s alertness, respiratory effort, and ability to take oral fluids. A small percentage of children < 5 years of age may present with abdominal pain or with fever and no signs of respiratory illness. (12) Although wheezing is more common in children with asthma it can be a manifestation of viral or mycoplasma pneumonia. A complete physical examination should be performed. A combination of clinical findings, including vital signs and pulse oximetry, is most predictive in determining CAP including: Infants < 12 months: Nasal flaring, O2 sat < 96%, tachypnea (RR > 50) and retractions Children 1 to 5 years: O2 sat< 96%, tachypnea (RR>40) Children > 5 years: O2 sat< 96%, tachypnea (RR>30) Consider the presence of parapneumonic effusion or empyema in children with pneumonia who present severely ill. Signs of pleural effusion include dyspnea, dry cough and pain over the chest wall, exaggerated by deep breathing, or coughing. Auscultatory findings may include a friction rub (leathery, rough inspiratory and expiratory breath sounds). Breath sounds may (13-14) also be diminished or absent over the affected areas. Laboratory Tests Empiric antibiotic therapy should not be delayed while awaiting diagnostic test results. Laboratory tests and chest x-rays should be ordered based on clinical findings. CBC should only be considered when adjunctive information is necessary to help (15-17) decide whether to use antibiotics. The likelihood of a bacterial cause generally increases as WBC counts increase 3 (17-18) above 15000/mm . Blood cultures are not routinely recommended in the evaluation of uncomplicated bacterial (19) pneumonia. In children with more severe disease, a blood culture may be helpful particularly if drawn prior to antibiotic treatment. PPD should be placed with history of exposure to TB including personal or family travel to TB prevalent areas. Nasopharyngeal swab for pertussis PCR should be obtained in children with cough lasting more than two weeks. Consider diagnostic tests for pertussis when typical symptoms are present. History: Assess for Age of child Immunization status, especially S. pneumoniae and influenza Exposure to TB © Evidence-Based Outcomes Center, 2008 Quality and Outcomes Center, Texas Children’s Hospital 1 DATE: October 2008 Critical Points of Evidence Evidence Supports Evidence Lacking/Inconclusive S.aureus is the most common pathogen isolated in children with Value of CBC for all children presenting with signs and symptoms of (11) (15-17) parapneumonic effusions at Texas Children's Hospital pneumonia Atypical organisms as a cause of CAP in children as young as 2 For treatment of pediatric empyema with fibrinolytic therapy versus 10, 20-21) (31) years ( VATS Use of penicillin (including amoxicillin) to treat uncomplicated Effectiveness of short course antibiotic therapy for uncomplicated (22-23) (36) pneumonia pneumonia Evidence Against Early video-assisted thorascopic surgery (VATS) should be considered for children with complicated pleural effusion or Use of blood cultures in the evaluation of CAP, in an outpatient (11, 24-27) (19) empyema setting (37) Therapies directed towards airway clearance Use of an antiviral such as oseltamivir within 48 hours of (28) symptom onset Fibrinolytics is a useful therapy option for children with (29-35) empyema Principles of Clinical Management General The clinical picture of children with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is highly variable making the determination of etiology difficult. The child’s age and severity of illness are important factors to consider in diagnosing and managing this (14) disease. (10, 38-39) Treatment Recommendations See Antibiotic Table on pages 4-5. Antibiotic Recommendations for Bacterial CAP, Uncomplicated- Outpatient The effectiveness of high dose amoxicillin has been demonstrated for acute otitis media and is considered a (40-41) reasonable option when treating other infections. Resistance of S. pneumoniae to penicillin is mediated through alterations in the penicillin-binding proteins. Using high-doses of amoxicillin saturates the penicillin-binding proteins and is (23) therefore considered a reasonable antibiotic option. Infants 1 to 4 months should be treated with high-dose amoxicillin + macrolide to cover S. pneumoniae and C. (42) trachomatis. Children > 4 months to 2 years should be treated with highdose amoxicillin for 10 days, to cover S. pneumoniae, the (43) most common etiologic cause of CAP. Children < 2 years who do not tolerate an initial dose of oral antibiotics should be treated with an IM dose of ceftriaxone. (44-46) Children ≥ 2 to 5 years should be treated with high-dose amoxicillin for 10 days ± macrolide for 5 days, to cover S. (47-49) pneumoniae and atypical pathogens. For optimal coverage, children ≥ 2 years should be treated with amoxicillin and a macrolide. When there is lesser concern, a single antibiotic can be used. If there is no clinical improvement within 24-48 hours, a second antibiotic should be added to the treatment. Children > 5 years should be treated with amoxicillin for 10 days and a macrolide for 5 days, to cover S. pneumoniae and (43, 47-49) atypical pathogens. Allergies: Children with a Type I penicillin allergy should be treated with azithromycin for 5 days ± clindamycin for 10 days. Children with non-Type I penicillin allergy should be treated with cephalosporin for 10 days ± macrolide for 5 days. © Evidence-Based Outcomes Center, 2008 Quality and Outcomes Center, Texas Children’s Hospital Antibiotic Recommendations for Bacterial CAP, Uncomplicated – Inpatient or Progressive Care It is likely that otherwise healthy children with uncomplicated pneumonia can be treated with β-lactam agents. The current susceptibilty profile at Texas Children's Hospital shows that 55% of S. pneumoniae isolates are susceptible to penicillin and 79% are (39) susceptible to cefOTAXime. Pneumococcal resistance to antibiotics has not been shown to affect clinical outcomes in children (50) (MIC < 2.0 μg/mL). If complications of pneumonia are suspected or pleural effusions are present, see Antibiotic Recommendations for Pleural Effusions. Based on expert consensus, infants 29 to 60 days should be treated with ampicillin and cefOTAXime to treat neonatal and communityacquired pathogens. Infants 1 to 4 months should be treated with cefOTAXime + (42) macrolide to cover S. pneumoniae and C. trachomatis. Children > 4 months to 2 years should be treated with ampicillin or (50-52) cefOTAXime, to cover S. pneumoniae. Children ≥ 2 to 5 years should be treated with ampicillin or cefOTAXime ± macrolide, to cover S. pneumoniae and atypical (50-52) pathogens. Children > 5 years should be treated with ampicillin or cefOTAXine + macrolide to cover S. pneumoniae and atypical pathogens. Transition child to oral antibiotics for a minimum 10 day course of antibiotics when there are signs of clinical improvement and defervescence, and the child is able tolerate PO. Antibiotic Recommendations for Bacterial CAP, Intensive Care Children < 2 years should be treated with cefOTAXime and vancomycin, to cover S. pneumoniae and S. aureus. Children ≥ 2 years should be treated with cefOTAXime and vancomycin ± macrolide, to cover S. pneumoniae, S. aureaus, and atypical pathogens. Antibiotic Recommendations for Pleural Effusions Treatment of children with CAP and small simple pleural effusions should be the same as children with CAP and no effusion. Children should be treated with clindamycin to cover S. aureus and S. pneumoniae. Ill appearing children should be treated with clindamycin and cefOTAXime. If child shows no signs of clinical improvement (i.e. persistent fever and/or leukocytosis, continuing 02 requirement, progression of radiographic findings) consider consulting Infectious Diseases and consider vancomycin. Transition child to oral antibiotics for a minimum of a three week course of antibiotics when there are signs of clinical improvement and defervescence, and the child is able to tolerate PO. 2 DATE: October 2008 Recommendations for Viral CAP Consider viral rapid tests based on patient’s history, time of year, and epidemiology. Oseltamivir for influenza in children ≥ 1 year with onset of (28) symptoms < 48 hours. Admission Criteria Unable to tolerate oral fluids and medications; severely dehydrated Moderate or severe respiratory distress Failed outpatient antibiotic treatment Altered mental status Oxygen saturation consistently < 90 % Unsafe to send home/poor follow-up Discharge Criteria Uncomplicated pneumonia Appropriate mental status for age Tolerating PO Appropriate support system (i.e. PMD, caregivers) Other Therapies Therapies directed towards airway clearance (i.e. postural drainage and chest physiotherapy) should not be used for (37) patients with uncomplicated pneumonia. Consider early video-assisted thorascopic surgery (VATS) for (24-27) children with complicated pleural effusion or empyema. Consider fibrinolytic therapy and thoracostomy tube for (29-35) children with complicated pleural effusion or empyema. Consults and Referrals Consultation with an ID specialist is considered when allergies or prior antibiotic non-responsiveness confound the choice of therapy. Consultation with a pulmonary or surgery specialist is appropriate when uncertain about management of an effusion (53-54) or persistent pneumonia. © Evidence-Based Outcomes Center, 2008 Quality and Outcomes Center, Texas Children’s Hospital Follow Up Care Children diagnosed with CAP who are not hospitalized should follow up with their pediatrician within 24 to 48 hours regardless of initiating antibiotic therapy. Follow up care is recommended for all children hospitalized with CAP. The child who is not following the expected clinical course, consider complications, viral etiology, TB, an alternative diagnosis, or ineffective antibiotic treatment due to lack of antibiotic coverage or resistance patterns. Outcomes Measures Failure to respond to antibiotic treatment - Unplanned readmit within 48 hours and type of antibiotic - Unplanned clinic revisit within 48 hours and type of antibiotic Need for surgery following fibrinolytic therapy and thoracostomy tube Length of stay (inpatient, intensive care) Mortality rate Direct variable costs Prevention Up-to-date heptavalent conjugated pneumococcal vaccine (55) (PCV7, Prevnar®) (28) Up-to-date annual influenza vaccine (56-58) Stress importance of strict hand washing Infection Control Contact precautions are required for children with upper (59) respiratory symptoms Droplet precautions are required if Pertussis is suspected AND (59) during influenza season in addition to contact precautions (59) Airborne precautions are required if TB is suspected Caregiver Education (60) Encourage breast feeding with infants (60) Limit exposure to other children (i.e. day care) Emphasize children should not be exposed to passive smoking; (61) explore smoking cessation options for parents 3 DATE: October 2008 Community-Acquired Pneumonia Antibiotic Table, Outpatient (38-39, 62-63) NOTE: Consider insurance/Medicaid formulary restrictions. Outpatient Therapy: First Line ≥ 2 yrs = High dose amoxicillin ± macrolide < 2 yrs = High-dose amoxicillin Type I Penicillin Allergy Non-Type I Penicillin Allergy Medication ≥5 yrs = amoxicillin + macrolide First Line: macrolide ± clindamycin First Line: cephalosporin ± macrolide Dosage Form and Flavor Taste & Aftertaste*(62-63) Dose Comments * 1 = Good 5 = Horrible (≥3 Consider asking the pharmacy to flavor; if possible.) Suspension (per 5 mL): 125, 200, 250 or 400 mg [Bubble Gum] Amoxicillin Infants & children: Oral: 80-100 mg/kg/DAY divided every 8-12 h (MAX: 3 grams/DAY) Chewable tablets: 125, 250 or 400 mg [Cherry Banana Mint] 1 Avoid use in patients with a penicillin allergy Adults: Oral: 500 mg every 8 h or 875 mg every 12 h Capsules: 250 or 500 mg Tablets: 500 or 875 mg Suspension (per 5 mL): 100 or 200 mg [Cherry Crème de Vanilla Banana] Azithromycin Infants & children ≥ 6 months: Oral: 10 mg/kg on day 1 (MAX: 500 mg/DAY) followed by 5 mg/kg/day once daily on days 2-5 (MAX: 250 mg/DAY) 3 Tablets: 250, 500 or 600 mg Extended Release Suspension: 2 gram [Cherry Banana] Suspension (per 5 mL): 125 or 250 mg [Fruit Punch] Clarithromycin Children ≥ 6 months: Oral: 15 mg/kg/DAY divided every 12 h (MAX: 1000 mg/day) 3 Tablets: 250 or 500 mg Adults: Oral: 500 mg on day 1 followed by 250 mg daily on days 2-5 or 2 gram extended release as a single dose First Line in patients with a Type I penicillin allergy (± clindamycin) Metallic Aftertaste Adults: Oral: 250 mg every 12 h or 1000 mg (two 500 mg extended release tablets) once daily Outpatient Therapy: Second Line Medication Dosage Form and Flavor Taste & Aftertaste*(62-63) Dose Comments * 1 = Good 5 = Horrible (≥3 Consider asking the pharmacy to flavor; if possible.) Suspension (per 5 mL): 125 or 250 mg [strawberry] Cefdinir Capsules: 300 mg 2 Adults: Oral: 300 mg every 12 h or 600 mg once daily (MAX: 600 mg/DAY) Infants & children ≥ 6 months: Oral: 10 mg/kg/DAY divided every 12 h (MAX: 800 mg/DAY) Suspension (per 5mL): 50 or 100mg [lemon creme] CefPODoxime Tablets: 100 or 200mg 4 Tablets: 250 or 500 mg 4 Injection ONLY: 1 or 2 gram Solution (per 5 mL): 75 mg [cherry flavor] Clindamycin Capsules: 75, 150 or 300 mg Adults: Oral: 250-500 mg every 12 h Infants >2 months & children: I.M., I.V.: 50-100 mg/kg/DAY IV or IM daily divided every 12-24 h (MAX: 50 mg/kg/dose or 2 gram/dose) N/A Ceftriaxone Adults: Oral: 100-400 mg every 12 h (MAX: 800mg/DAY) Infants & children ≥ 6 months: Oral: 30 mg/kg/day divided every 12 h (MAX: 1gram/DAY) Suspension (per 5 mL): 125 or 250 mg [Tutti-Frutti] CefUROxime Infants & children ≥ 6 months: Oral: 14 mg/kg/DAY divided every 12 h or 14 mg/kg/DAY once daily (MAX: 600 mg/DAY) Adults: I.M., I.V.: 1 gram IV or IM once daily (usually in combination with a macrolide) Infants & children: Oral: 10-30 mg/kg/DAY divided every 6-8 hours (MAX: 1.8 gram/DAY) 5 Expert Consensus Dosing: 10-40 mg/kg/DAY divided every 6-8 hours (MAX: 1.8 gram/DAY) 3rd Generation Caution use in patients with a Type I penicillin allergy 3rd Generation Caution use in patients with a Type I penicillin allergy 2nd Generation Caution use in patients with a Type I penicillin allergy 3rd Generation Caution use in patients with a Type I penicillin allergy May offer a onetime dose prior to initiating oral antibiotics Add if concerned for MRSA, S. aureus Major side effect: Diarrhea Adolescents &adults: Oral: 150-450 mg/dose every 6-8 hours; (MAX: 1.8 gram/DAY) © Evidence-Based Outcomes Center, 2008 Quality and Outcomes Center, Texas Children’s Hospital 4 DATE: October 2008 Community-Acquired Pneumonia Antibiotic Table, Inpatient (38-39, 62-63) NOTE: Consider insurance/Medicaid formulary restrictions. Inpatient Therapy: Acute Care Status / Progressive Care Unit Uncomplicated Pneumonia: Complicated Pneumonia: Medication < 2 yrs = ampicillin or cefOTAXime All patients: cefOTAXime & clindamycin Taste & Dosage Form and Flavor Aftertaste*(62-63) ≥ 2 yrs = ampicillin or cefOTAXime ± macrolide Dose Comments * 1 = Good 5 = Horrible (≥3 Consider asking the pharmacy to flavor; if possible.) Ampicillin Injection: 125, 250, or 500 mg 1 or 2 gram Infants & children: I.V.: 200 mg/kg/DAY divided every 6 h (MAX: 2 gram/dose or 12 gram/DAY) N/A Injection: 40 mg/mL or 200 mg/mL (Central Line) N/A CefOTAXime Suspension (per 5 mL): 100 or 200 mg [Cherry Crème de Vanilla Banana] Adults: I.V.: 1000 mg every 4-6 h (MAX: 2 gram/dose or 12 gram/DAY) Infants > 1 month to Children 1 year: I.V.: 75 mg/kg/dose every 8 h Children ≥ 1 year: I.V.: 50-75 mg/kg/dose every 8 h (MAX: 2 gram/dose) Adults: I.V.: Moderate to severe infection: 1-2 gram/dose every 6-8 h (MAX: 2 gram/dose) or Life-threatening infection: 2 gram/dose every 4 h (MAX: 2 gram/dose or 12 gram/DAY) Infants & children ≥ 6 months: Oral: 10 mg/kg on day 1 (MAX: 500 mg/DAY) followed by 5 mg/kg/day once daily on days 2-5 (MAX: 250 mg/DAY) I.V.: 10 mg/kg/DAY once daily (MAX: 500 mg/dose) Tablets: 250, 500 or 600 mg Azithromycin 3 Extended Release Suspension: 2 gram [Cherry Banana] Injection: 125, 250, or 500 mg 1 or 2 gram Suspension (per 5 mL): 125 or 250 mg [Fruit Punch] Clarithromycin Tablets: 250 or 500 mg Avoid use in patients with a penicillin allergy Caution use in patients with a Type I penicillin allergy First Line in patients with a Type I penicillin allergy (± clindamycin) Adults: Oral: 500 mg on day 1 followed by 250 mg daily on days 2-5 or 2 gram extended release as a single dose I.V.: 10 mg/kg/DAY once daily (MAX: 500 mg/dose) Children ≥ 6 months: Oral: 15 mg/kg/DAY divided every 12 h (MAX: 1000 mg/DAY) 3 Metallic Aftertaste Solution (per 5mL): 75 mg [cherry flavor] Adults: Oral: 250 mg every 12 h or 1000 mg (two 500 mg extended release tablets) once daily Infants & children: Oral: 10-30 mg/kg/DAY divided every 6-8 h (MAX: 1.8 grams/DAY) I.M., I.V.: 25-40 mg/kg/DAY divided every 6-8 h (MAX: 2.7 grams/DAY) Add if concerned for MRSA, S. aureus Expert Consensus Dosing: 30-40 mg/kg/DAY divided every 6-8 h (MAX: 2.7 grams/DAY) Major side effect: Diarrhea Capsules: 75, 150 or 300 mg Clindamycin 5 Injection: 150 mg/mL (IM) , 18 mg/mL (IV) Adolescents & adults: Oral: 150-450 mg/dose every 6-8 h (MAX: 1.8 grams/DAY) I.M., I.V.: 1.2-2.7grams/DAY in 2-4 divided doses Inpatient Therapy: Intensive Care Status (PICU) Medication < 2 yrs = cefOTAXime& vancomycin Taste & Dosage Form and Flavor Aftertaste*(62-63) ≥ 2 yrs = cefOTAXime & vancomycin ± macrolide Dose Comments * 1 = Good 5 = Horrible (≥3 Consider asking the pharmacy to flavor; if possible.) Injection: 40 mg/mL or 200 mg/mL (Central Line) N/A CefOTAXime Injection: 5 mg/mL Vancomycin Azithromycin Infants >1 month to children 1 year: I.V.: 75 mg/kg/dose every 8 h Injection: 125, 250, or 500 mg 1 or 2 gram N/A N/A Injection: 150 mg/mL (IM) , 18 mg/mL (IV) Clindamycin N/A Children ≥ 1 year: I.V.: 50-75 mg/kg/dose every 8 h (MAX: 2 gram/dose) Caution use in patients with a Type I penicillin allergy Adults: I.V.: Moderate to severe infection: 1-2 gram/dose every 6-8 h (MAX: 2 gram/dose) or Life-threatening infection: 2 gram/dose every 4 h (MAX: 2 gram/dose or 12 gram/DAY) Infants >2 months & children: I.V.: 13-15 mg/kg/dose IV every 8 h (MAX: 1.5 gram/dose or 4 gram/DAY) Adults: I.V.: 13-15 mg/kg/dose IV every 8-12 h (MAX: 1.5 gram/dose or 4 gram/DAY) Infants & children: I.V.: 10 mg/kg/DAY once daily (MAX: 500 mg/dose) Adults: I.V.: 10 mg/kg/DAY once daily (MAX: 500 mg/dose) Infants & children: I.M., I.V.: 25-40 mg/kg/DAY divided every 6-8 h (MAX: 2.7 grams/DAY) Expert Consensus Dosing: 30-40 mg/kg/DAY divided every 6-8 hours (MAX: 2.7 grams/DAY) Add if concerned for MRSA, S. aureus Major side effect: Diarrhea Adolescents & adults: I.M., I.V.: 1.2-2.7 grams/DAY in 2-4 divided doses © Evidence-Based Outcomes Center, 2008 Quality and Outcomes Center, Texas Children’s Hospital 5 DATE: October 2008 TCH Evidence- Based Clinical Decision Support Clinical Algorithm for Community-Acquired Pneumonia (CAP) * Based on history, time of year, and epidemiology. Other tests include: PPD, PCR ( i.e. Pertussis, other ) and serologies for specific pathogens. Initial clinical findings suggestive of CAP Begin Manage as appropriate to clinical findings ( OFF Algorithm ) No Yes ~ Complications of CAP - Pleural effusion/empyema - Respiratory failure - Sepsis - Lung abscess - Pneumatocele Suspect pleural effusion~ Follow Presumed Infectious Pleural Effusion Algorithm Yes No Continuum of Respiratory Severity Mild Moderate - Respiratory assessment Rate 2-12 months < 40 1-5 years < 30 > 5 years < 20 Good air movement, loose rales/ crackles Mild to no use of accessory muscles/retractions, +/- nasal flaring on inspiration - Normal to mildly irritable behavior - Pulse oximetry > 95% room air - Normal color - Respiratory assessment Rate 2-12 months 40-50 1-5 years 30-40 > 5 years 20-30 Depressed air movement, crackles Moderate intercostal retractions, mild to moderate use of accessory muscles, nasal flaring - Irritable, agitated, restless - Pulse oximetry 90 to 95% room air - Pale to normal color - Respiratory assessment Rate 2-12 months > 60 1-5 years > 50 > 5 years > 30 Diminished or absent breath sounds, severe crackles, prolonged expiration Severe intercostal and substernal retractions, nasal flaring - Lethargic - Pulse oximetry < 90% room air - Cyanotic, dusky color Consider Diagnostic Tests: - CXR - CBC diff - Blood culture - Viral rapid tests* - PPD - Other tests* Diagnostic Tests: - CXR - CBC diff/plt - Chem 7 - Blood culture ----------------------------------Consider: - Viral rapid tests* - Viral cultures* - Bacterial cultures of respiratory specimens - Other tests* Suspect typical/ atypical bacterial CAP No Yes PPD if history of exposure Initiate Antibiotic Therapy^ Discharge Home Follow up with pediatrician within 48 hours ^ Antibiotics for Outpatient Therapy - age 1 to 4 months high dose amoxicillin + macrolide for S. pneumoniae and C. trachomatis - age 4 months to 2 years high dose amoxicillin for typical bacterial pathogens - age ≥ 2 to 5 years high dose amoxicillin ± macrolide for typical/atypical bacterial pathogens - > 5 years amoxicillin + macrolide ( See abx table, p.4 ) Viral CAP suspected Severe Bacterial CAP suspected Consider Viral rapid tests* Initiate antiviral tx if sx < 48 hours Yes Discharge Home Follow up © Evidence-Based Outcomes Center, 2008 with pediatrician Quality and Outcomes Center, Texas Children’s Hospital within 48 hours Suspect complicated pneumonia~ Yes Initiate Antibiotic Therapy Follow Presumed Infectious Pleural Effusion Algorithm Discharge Criteria: Uncomplicated pneumonia Appropriate mental status for age Taking PO fluids Appropriate support system Admit for clinical monitoring if ill appearing OR ↑ work of breathing No Admit for IV Antibiotics‡ ‡ No Antibiotics for Inpatient Therapy - age 1 to 4 months cefOTAXime + macrolide to cover S. pneumoniae and C. trachomatis - age 4 months to 2 years ampicillin or cefOTAXime for typical bacterial pathogens - age ≥ 2 to 5 years ampicillin or cefOTAXime ± macrolide for typical/atypical bacterial pathogens - > 5 years ampicillin or cefOTAXime + macrolide ( See abx table, p.5 ) Observation OR Admit for IV Antibiotics‡ 6 DATE: October 2008 TCH Evidence- Based Clinical Decision Support Clinical Algorithm for Presumed Infectious Pleural Effusions Complications of Community-Acquired Pneumonia - Pleural effusion/empyema - Respiratory failure - Sepsis - Lung abscess - Pneumatocele Suspect Infectious Pleural Effusion CXR CXR demonstrates pleural effusion Yes Prepare for admission °Indications of Complicated Effusion: - Large effusion ( > 10-20% ) - Ill appearing - Develops hypoxemia - Worsening symptoms OFF Algorithm/Return to CAP Algorithm No Suspect complicated effusion° No - Chest US - Consider surgery consultation Yes No Need for Intervention Yes - CBC diff/plt - Chem 7 - Blood culture - Initiate antibiotic therapy◘ - Monitor clinically Clinical improvement Treat organized fluid collections with VATS or fibrinolytics and thoracostomy tube Yes - CBC diff/plt - Chem 7 - Blood culture - Initiate antibiotic therapy◘ -------------------------------------------------------Select: - VATS and thoracostomy tube - Fibrinolytics and thoracostomy tube - Thoracentesis - Percutaneous thoracostomy ( pigtail, small drain, chest tube ) Yes Successful procedure No No - Repeat chest x-ray - Consider repeat chest US - Consider ID, pulmonary and/or surgery consultation Consider ID, pulmonary and/or surgery consultation VATS Continue antibiotic therapy/clinical monitoring until discharge criteria∆ are met Key: CAP- community-acquired pneumonia ID- infectious disease US- ultrasound video-assisted thorascopic surgery ©VATSEvidence-Based Outcomes Center, 2008 Quality and Outcomes Center, Texas Children’s Hospital Continue antibiotic therapy/clinical monitoring until discharge criteria∆ are met ◘ Antibiotics for Inpatient Therapy, Pleural Effusions - Clindamycin to cover S. aureus and S. pneumoniae - Clindamycin and cefOTAXime for ill appearing children ∆ Discharge Criteria - No oxygen requirement - Tolerating PO - Chest tube removed - Appropriate mental status for age - Signs of clinical improvement and defervescence - Appropriate support system ( PCP, 7 caregiver ) DATE: October 2008 References 1. Community Acquired Pneumonia Guideline Team, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center: Evidence-based care guideline for medical management of Community Acquired Pneumonia in children 60 days to 17 years of age, http://www.cincinnatichildrens.org/svc/alpha/h/health-policy/ev-based/pneumonia.htm , Guideline 14, pages 1-16, December 22, 2005. 2. Whitney, C. G., Farley, M. M., Hadler, J., Harrison, L. H., Bennett, N. M., Lynfield, R., et al. (2003). Decline in invasive pneumococcal disease after the introduction of protein-polysaccharide conjugate vaccine. The New England Journal of Medicine, 348(18), 1737-1746. 3. Korppi, M., Heiskanen-Kosma, T., & Kleemola, M. (2004). Incidence of community-acquired pneumonia in children caused by mycoplasma pneumoniae: Seriological results of a prospective, population-based study in primary health care. Respirology, 9, 109-114. 4. Heiskanen-Kosma, T., Korppi, M., & Leinonen, M. (2003). Serologically indicated pneumococcal pneumonia in children: A populationbased study in primary care settings. APMIS, 111, 945-950. 5. Juvén, T., Mertsola, J., Waris, M., Leinonen, M., Meurman, O., Roivainen, M., et al. (2000). Etiology of community-acquired pneumonia in 254 hospitalized children. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 19, 293-296. 6. Korppi, M., Heiskanen-Kosma, T., Saikku, P., Leinonen, M., Halonen, P., Mäkela, P. H., et al. (1993). Aetiology of community-acquired pneumonia in children treated in hospital. Eur J Pediatr, 152, 24-30. 7. Williams, J. V., Harris, P. A., Tollefson, S. J., Halburnt-Rush, L. L., Pingsterhaus, J. M., Edwards, K. M., et al. (2004). Human metapneumovirus and lower respiratory tract disease in otherwise healthy infants and children. The New England Journal of Medicine, 350(5), 443-450. 8. Laundy, M., Ajayi-Obe, E., Hawrami, K., Aitken, C., Breuer, J., & Booy, R. (2003). Influenza A community-acquired pneumonia in east London infants and young children. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 22(10), s223-227. 9. Murphy, T. F., Henderson, F. W., Clyde, W. A., Collier, A. M., & Denny, F. W. (1981). Pneumonia: An eleven-year study in a pediatric practice. American Journal of Epidemiology, 113(1), 12-21. 10. Michelow, I. C., Olsen, K., Lozano, J., Rollins, N. K., Duffy, L. B., Ziegler, T., et al. (2004). Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of community-acquired pneumonia in hospitalized children. Pediatrics, 113(4), 701-707. 11.Schultz, K. D., Fan, L. L., Pinsky, J., Ochoa, L., Smith, E. O. B., Kaplan, S. L., et al. (2004). The changing face of pleural empyemas in children: Epidemiology and management. Pediatrics, 113(6), 1735-1740. 12. Seidel, H. M., Ball, J. W., Dains, J. E., & Benedict, G. W. (1999). Mosby's Guide to Physical Examination (5th ed.). St. Louis: Mosby. 13. Balfour-Lynn, I. M., Abrahamson, E., Cohen, G., Hartley, J., King, S., Parikh, D., et al. (2005). BTS guidelines for the management of pleural infection in children. Thorax, 60(suppl_1), i1-21. 14. Behrman, R. E., Kleigman, R. M., & Jenson, H. B. (2004). Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics (17th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders. 15. Korppi, M. (2004). Non-specific host response markers in the differentiation between pneumococcal and viral pneumonia: What is the most accurate combination? Pediatrics International, 46, 545-550. 16. Toikka, P., Irjala, K., Juvén, T., Virkki, R., Mertsola, J., Leinonen, M., et al. (2000). Serum procalcitonin, c-reactive protein and interleukin-6 for distinguishing bacterial and viral pneumonia in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 19, 598-602. 17. Bachur, R., Perry, H., & Harper, M. B. (1999). Occult pneumonias: Empiric chest radiographs in febrile children with leukocytosis. Ann Emerg Med, 33(2), 166-173. 18. Shuttleworth, D. B., & Charney, E. (1971). Leukocyte count in childhood pneumonia. Amer J Dis Child, 122, 393-396. 19. Hickey, R. W., Bowman, M. J., & Smith, G. A. (1996). Utility of blood cultures in pediatric patients found to have pneumonia in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med, 27, 721-725. 20. Somer, A., Salman, N., Yalcin, I., & Agacfidan, A. (2006). Role of mycoplasma pneumoniae and chlamydia pneumoniae in children with community-acquired pneumonia in Istanbul, Turkey. J Trop Pediatr, 52(3), 173-178. 21. Esposito, S., Bosis, S., Cavagna, R., Faelli, N., Begliatti, E., Marchisio, P., et al. (2002). Characteristics of streptococcus pneumoniae and atypical bacterial infections in children 2-5 years of age with community-acquired pneumonia. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 35, 1345-1352. 22. McCracken, G. H. (2000). Etiology and treatment of pneumonia. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 19, 373-377. 23. Pallares, R., Liñares, J., Vadillo, M., Cabellos, C., Manresa, F., Viladrich, P. F., et al. (1995). Resistance to penicillin and cephalosporin and mortality from severe pneumococcal pneumonia in Barcelona, Spain. The New England Journal of Medicine, 333, 474-480. 24. Gates, R. L., Caniano, D. A., Hayes, J. R., & Arca, M. J. (2004). Does VATS provide optimal treatment of empyema in children? A systematic review. Journal of Pediatric Surgery, 39(3), 381-386. 25. Kurt, B. A., Winterhalter, K. M., Connors, R. H., Betz, B. W., & Winters, J. W. (2006). Therapy of parapneumonic effusions in children : Video-assisted thorascopic surgery versus conventional thorascostomy drainage. Pediatrics, 118, 547-553. 26. Aziz, A., Healey, J. M., Qureshi, F., Kane, T. D., Kurland, G., Green, M., et al. (2008). Comparative analysis of chest tube thoracostomy and video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery in empyema and parapneumonic effusion associated with pneumonia in children. Surgical Infections, 9(3), 317-323. 27. Shah, S. S., DiCristina, C. M., Bell, L. M., Ten Have, T., & Metlay, J. P. (2008). Primary early thoracoscopy and reduction in length of hospital stay and additional procedures among children with complicated pneumonia: Results of a multicenter retrospective cohort study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med, 162(7). 28. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention and Control of Influenza: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Early Release; 57 [August 1, 2008]: 36-38. 29. Avansino, J. R., Goldman, B., Sawin, R. S., & Flum, D. R. (2005). Primary operative versus nonoperative therapy for pediatric empyema: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 115(6), 1652-1659. 675-681. © Evidence-Based Outcomes Center, 2008 Quality and Outcomes Center, Texas Children’s Hospital 8 DATE: October 2008 References continued… 30. Singh, M., Mathew, J. L., Chandra, S., Katariya, S., & Kumar, L. (2004). Randomized controlled trial of intrapleural streptokinase in empyema thoracis in children. Acta Paediatrica, 93(11), 1443-1445. 31. Sonnappa, S., Cohen, G., Owens, C. M., van Doorn, C., Cairns, J., Stanojevic, S., et al. (2006). Comparison of urokinase and videoassisted thoracoscopic surgery for treatment of childhood empyema. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 174, 221-227. 32. Thomson, A. H., Hull, J., Kumar, M. R., Wallis, C. & Balfour Lyn, I. M. (2002). Randomised trial of intrapleural urokinase in the treatment of childhood empyema. Thorax, 57, 343-347. 33. Wang, J. N., Yao, C. T., Yeh, C. N., Liu, C. C., Wu, M. H., Chuang, H. Y., et al. (2006). Once-daily vs. twice-daily intrapleural urokinase treatment of complicated parapneumonic effusion in paediatric patients: A randomised, prospective study. International Journal of Clinical Practice, 60(10), 1225-1230. 34. Cohen, E., Weinstein, M., & Fisman, D. N. (2008). Cost-effectiveness of competing strategies for the treatment of pediatric empyema. Pediatrics, 121(5), e1250-1257. 35. Cochran, J. B., Tecklenburg, F. W., & Turner, R. B. (2003). Intrapleural instillation of fibrinolytic agents for treatment of pleural empyema. Pediatr Crit Care Med, 4(1), 39-43. 36. Haider B. A., Saeed M. A., & Bhutta Z. A. (2008). Short-course versus long-course antibiotic therapy for non-severe communityacquired pneumonia in children aged 2 months to 59 months [Electronic Version]. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, from http://www.mrw.interscience.wiley.com/cochrane/clsysrev/articles/CD005976/frame.html . 37. Hardy, K. A. (1994). A review of airway clearance: New techniques, indications, and recommendations. Respiratory Care, 39(5), 440455. 38. Texas Children's Hospital Drug Information and Formulary. 9th ed. Hudson (OH): Lexi-Comp; 2007. 39. Texas Children’s Hospital: Antibiotic Susceptibility Report. 2007. 40. Piglansky, L., Leibovitz, E., Raiz, S., Greenberg, D., Press, J., Leiberman, A., et al. (2003). Bacteriologic and clinical efficacy of high dose amoxicillin for therapy of acute otitis media in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 22(5), 405-412. 41. Jadavji, T., Law, B., Lebel, M. H., Kennedy, W. A., Gold, R., & Wang, E. E. L. (1997). A practical guide for the diagnosis and treatment of pediatric pneumonia. Can Med Assoc J, 156(5), S703-711.41. 42.McIntosh, K. (2002). Community-acquired pneumonia in children. N Engl J Med, 346(6), 429-437. 43. Aurangzeb, B., & Hammeed, A. (2003). Comparative efficacy of amoxicillin, cefuroxime and clarithromycin in the treatment of community acquired pneumonia in children. JCSP, J College Phys & Surg- Pakistan, 13(12), 704-707. 44. Klein, J. O. (1997). History of macrolide use in pediatrics. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 16(4), 427-431. 45. Baskin, M. N., O'Rourke, E. J., & Fleisher, G. R. (1991). Outpatient treatment of febrile infants 28 to 29 days of age with intramuscular administration of ceftriaxone. Journal of Pediatrics, 120(22-27). 46. Chumpa, A., Bachur, R. G., & Harper, M. B. (1999). Bacteremia-associated pneumococcal pneumonia and the benefit of initial parenteral antimicrobial therapy. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal, 18(12), 1081-1085. 47. Bartlett, J. G., & Mundy, L. M. (1995). Community-acquired pneumonia. The New England Journal of Medicine, 26(4), 811-838. 48. Wubbel, L., Muniz, L., Ahmed, A., Trujillo, M., Carubelli, C., McCoig, C., et al. (1999). Etiology and treatment of community-acquired pneumonia in ambulatory children. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 18(2), 98-104. 49. Harris, J. A., Kolokathis, A., Campbell, M., Cassell, G. H., & Hammerschlag, M. R. (1998). Safety and efficacy of azithromycin in the treatment of community-acquired pneumonia in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 17(10), 865-871. 50. Tan, T. Q., Mason, E. O., Barson, W. J., Wald, E. R., Schutze, G. E., Bradley, J. S., et al. (1998). Clinical characteristics and outcome of children with pneumonia attributable to penicillin-susceptible and penicillin-nonsusceptible streptococcus pneumoniae. Pediatrics, 102(6), 1369-1375. 51. Atkinson, M., Lakhanpaul, M., Smyth, A., Vyas, H., Weston, V., Sithole, J., et al. (2007). Comparison of oral amoxicillin and intravenous benzyl penicillin for community acquired pneumonia in children (PIVOT trial): A multicentre pragmatic randomised controlled equivalence trial. Thorax, 62(12), 1102-1106. 52. Yu, V. L., Chiou, C. C., Feldman, C., Ortqvist, A., Rello, J., Morris, A. J., et al. (2003). An international prospective study of pneumococcal bacteremia: Correlation with in vitro resistance, antibiotics administered, and clinical outcome. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 37, 230-237. 53. Hardie, W., Bokulic, R., Garcia, V. F., Reising, S., & Christine, C. D. C. (1996). Pneumococcal pleural empyemas in children. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 22, 1057-1063. 54. Byington, C. L., Spencer, L. Y., Johnson, T. A., Pavia, A. T., Allen, D., Mason, E. O., et al. (2002). An epidemiological investigation of a sustained high rate of pediatric parapneumonic empyema: Risk factors and microbiological associations. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 34, 434-440. th 55. AAP: American Academy of Pediatrics Red Book. 26 Edition, 2003. 56. Morton, J. L., & Schultz, A. A. (2004). Healthy hands: Use of alcohol gel as an adjunct to handwashing in elementary school children. The Journal School of Nursing, 20(3), 161-167. 57. Roberts, L., Smith, W., Jorm, L., Patel, M., Douglas, R. M., & McGilchrist, C. (2000). Effect of infection control measures on the frequency of upper respiratory infection in child care: A randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics, 105, 738-742. 58. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guideline for Hand Hygiene in Health-Care Settings: Recommendations of the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee and the HICPAC/SHEA/APIC/IDSA Hand Hygiene Task Force, MMWR 2002; 51 (no. RR- 16). 59. Siegel JD, Rhinehart E, Jackson M, Chiarello L, and the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee, 2007 Guideline for Isolation Precautions: Preventing Transmission of Infectious Agents in Healthcare Settings, June 2007, http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dhqp/pdf/isolation2007.pdf . © Evidence-Based Outcomes Center, 2008 Quality and Outcomes Center, Texas Children’s Hospital 9 DATE: October 2008 References continued… 60. Levine, O. S., Farley, M., Harrison, L. H., Lefkowitz, L., McGeer, A., & Schwartz, B. (1999). Risk factors for invasive pneumococcal disease in children: A population-based case-control study in North America. Pediatrics, 103, e28. 61. Almirall, J., González, C. A., Balanzó, X., & Bolíbar, I. (1999). Proportion of community-acquired pneumonia cases attributable to tobacco smoking. Chest, 116, 375-379. 62. Steele, R. W. M., Thomas, M. P. P., & Begue, R. E. M. (2001). Compliance issues related to the selection of antibiotic suspensions for children. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal, 20(1), 1-5. 63. Powers, J. L. M., Gooch, W. M. I. M. M., & Oddo, L. P. B. (2000). Comparison of the palatability of the oral suspension of cefdinir vs. amoxicillin/clavulanate potassium, cefprozil and azithromycin in pediatric patients. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal, 19(12)(Supplement), S174-S180. © Evidence-Based Outcomes Center, 2008 Quality and Outcomes Center, Texas Children’s Hospital 10 DATE: October 2008 Guideline Preparation Evaluating the Quality of the Evidence This guideline was prepared by the Evidence-Based (EB) Clinical Decision Support Team in collaboration with content experts at Texas Children’s Hospital. Development of this guideline supports the TCH Quality and Patient Safety Program initiative to promote clinical guidelines and outcomes that build a culture of quality and safety within the organization. The Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) criteria were used to evaluate the quality of articles reviewed. Application of the CASP criteria are completed by rating each reviewed study or review as: Strong study/systematic review - well designed, well conducted, adequate sample size, reliable measures, valid results, appropriate analysis, and clinically applicable/relevant. Study/systematic review with minor limitations specifically lacking in one of the above criteria Study/systematic review with major limitations specifically lacking in several of the above criteria. Published clinical guidelines evaluated for this review using the AGREE criteria. The summary of these guidelines are found at the end of this document. AGREE criteria uses a 14 point likert scale to evaluate 23 questions evaluating: Guideline Scope and Purpose, Stakeholder Involvement, Rigor of Development, Clarity and Presentation, Applicability, and Editorial Independence. The higher the score the more comprehensive the guideline. Community-Acquired Pneumonia Content Expert Team Aderonke Adekunle-Ojo, MD, Emergency Medicine Christopher Baldez, LCSW, Social Work Sara Bork, PharmD, Pharmacy Darrell Cass, MD, Pediatric Surgery Christopher Cassady, MD, Radiology Emily Charles, Care Coordinator, Care Management Michael Chance, Quality Improvement Specialist, Quality and Outcomes Measurement Kim Davis, RT, Respiratory Care Leland Fan, MD, Pulmonary Tiffany Helme, RN, Emergency Center Curtis Kennedy, MD, Critical Care Medicine Daniel Lemke, MD, Emergency Medicine Ned Nuchtern, MD, Pediatric Surgery Flor Munoz-Rivas, MD, Infectious Diseases Elena Ocampo, MD, Cardiology Shea Palamountain, MD, Texas Children’s Pediatric Associates Ricardo Quinonez, MD, Pediatric Hospital Medicine Elaine Whaley, RN, Infection Control EB Clinical Decision Support Team Quinn Franklin, MS, CCLS Research Specialist Marilyn Hockenberry, PhD, RN, PNP-CS, FAAN Co-Chair Development Process This guideline was developed using the process outlined in the EB Clinical Decision Support Manual (2007). The review summary documents the following steps: 1. Review Preparation -PICO questions established -Evidence search confirmed with content experts 2. Review of Existing Internal and External Guidelines - British Thoracic Society (BTS) guidelines and a published guideline from a children’s hospital 3. Literature Review of Relevant Evidence -Searched: Medline, Cochrane, AHRQ, CINAHL, Trip, Best BETS, AAP, BMJ Clinical Evidence, Google Scholar 4. Critically Analyze the Evidence - BTS Guidelines, Cincinnati Guideline, three systematic reviews, one meta-analysis, nine randomized control trials, and twenty-one non-randomized studies. 5. Summarize the Evidence by preparing the guideline, order sets and interdisciplinary plan of care -Materials used in the development of the guidelines, review summaries and content expert team meeting minutes are maintained in an community-acquired pneumonia EB review manual with the Quality and Outcomes Center. © Evidence-Based Outcomes Center, 2008 Quality and Outcomes Center, Texas Children’s Hospital This guideline specifically summarizes the evidence in support of or against specific interventions and identifies where evidence is lacking/inconclusive. The following categories describe how research findings provide support for treatment interventions. “Evidence that supports” the guideline (p.2) provides clear evidence from more than one well-done randomized controlled trial (RCT) (based on CASP criteria) that the benefits of the intervention exceed harm. “Evidence against” (p.2) provides clear evidence from more than one well-done RCT (based on CASP criteria) that the intervention is likely to be ineffective or that it is harmful. “Evidence lacking/inconclusive” (p.2) indicates there is currently insufficient data or inadequate data to recommend for or against specific intervention. Recommendations Recommendations for the guidelines were developed by a consensus process directed by the existing evidence, content experts and patient and family preference when possible. The Content Expert Team and EB Clinical Decision Support Team remain aware of the controversies in the management of community-acquired pneumonia in children. When evidence is lacking, options in care are provided in the guideline and the order sets that accompany the guideline. Approval Process Guidelines are reviewed and approved by the Content Expert Team, EB Clinical Decision Support Team, EB Executive Steering Committee, Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee and other appropriate hospital committees as deemed appropriate for the guideline’s intended use. Guidelines are reviewed and updated as necessary every 2 to 3 years within the EB Clinical Decision Support Team at Texas Children’s Hospital. Content Expert Teams will be involved with every review and update. Disclaimer Guideline recommendations are made from the best evidence, expert opinions and consideration for the patients and families cared for within TCH/TCPA. The guideline is NOT intended to impose standards of care preventing selective variation in practice that are necessary to meet the unique needs of individual patients. The physician must consider each patient’s circumstance to make the ultimate judgment regarding best care. 11